46 Gastrointestinal Devices, Procedures, and Imaging

• Nonfunctional feeding tubes can be safely replaced in the emergency department with a commercial tube or by making a few simple alterations to a standard Foley catheter to prolong its longevity.

• Gastroesophageal balloon tamponade tubes are used only for life-threatening variceal bleeding that is refractory to standard, first-line endoscopic and pharmacologic treatment. There is no absolute contraindication to the use of such tubes as a heroic, lifesaving measure.

Nasogastric Tubes

The Salem Sump tube is the most commonly used nasogastric tube (NGT) in the emergency department (ED). The Salem Sump is a double-lumen tube with multiple distal suction eyes. The second lumen allows venting during suction, which prevents invagination and subsequent gastric injury. Indications for its use include gastric evacuation or decompression, diagnostic aspiration of gastric contents, and infusion of therapeutic agents. Intermittent suction may be set at a pressure of less than 120 mm Hg.1 A Levin tube is a single-lumen tube with multiple distal openings for suction, referred to as “eyes.” The Levin tube’s relatively large internal diameter makes it ideal for rapid decompression or drug infusion. Intermittent suction may be set at a level lower than 40 mm Hg. A Levin tube has the same uses as the Salem tube except that it may not be used for long-term gastric evacuation.1

Indications and Contraindications

Box 46.1 lists the indications for and contraindications to the use of NGTs in the ED.

Box 46.1 Indications for and Contraindications to the Use of Nasogastric Tubes

Indications

In gastrointestinal bleeding, to monitor blood loss, which may help differentiate upper from lower tract sources of bleeding

In intubated patients, to decrease risk for pulmonary aspiration, treat gastric distention, and deliver medications

Decompression of intestinal obstruction

Treatment of paralytic ileus, intractable vomiting

Treatment of gastric outlet obstruction and distention

In trauma patients, to evaluate for transdiaphragmatic hernia when the nasogastric tube is seen above the diaphragm on a chest radiograph

Rightward deviation of the tube may be seen on a chest radiograph in patients with aortic dissection

Insertion Procedure

Tips and Tricks

Inserting a Nasogastric Tube

Warming the tube will make it more pliable and easier to advance along the curvature from the nasopharynx into the oropharynx.

Flexing the patient’s neck can help direct the tube from the oropharynx into the esophagus.

If choking, gagging, or muffling of the voice occurs, withdraw the tube to the oropharynx only. Do not remove the tube completely, or it must be repassed through the nasopharynx into the oropharynx, which is usually the most difficult and painful part of the procedure.

The tube can coil within the patient’s mouth; if problems occur when placing or verifying placement of the tube, always check the mouth.

In an unconscious patient, elevating the jaw will move the trachea anteriorly, a maneuver that can relieve pressure on the esophagus and make it easier to pass the tube.2

A lubricated, soft nasopharyngeal airway may be inserted if neither naris appears to be amenable to placement of the larger, more rigid nasogastric tube (NGT). The nasopharyngeal airway may be used to dilate the nasal passage for a few minutes and then removed to allow another attempt at placing the NGT. Alternatively, a smaller NGT may be passed through the nasopharyngeal airway into the esophagus.

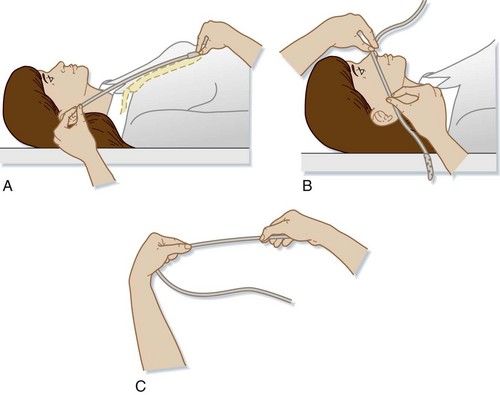

1 Estimation of Tube Length

To place the drainage eyes in the proper location in the stomach (Fig. 46.1), the length of tube to be inserted can be estimated by adding the following three measurements together3:

a: Measurement from the patient’s xiphoid process to the earlobe

2 Nares Patency Check, Anesthesia, and Vasoconstriction

Pretreatment Medications

Placement of an NGT is one of the most painful routine procedures performed in the ED. In nonemergency situations it is best practice to treat the patient with nasal vasoconstrictors and anesthetics before placing the tube.4

Application of lidocaine before inserting an NGT has been shown to significantly decrease pain during the procedure.5–7 Lidocaine can be delivered as viscous, nebulized, or atomized preparations. Application of viscous lidocaine to the nasal passage combined with lidocaine spray applied to the posterior pharynx has been shown to be superior to other forms of anesthetics when placing an NGT or transnasal bronchoscope.6,8 However, no definitive study or review article has determined the best concentration, form, or dose of lidocaine to use.7

lidocaine options

• Viscous lidocaine—5 to 10 mL of 2% lidocaine applied to an adult nasal passage 0 to 5 minutes before NGT placement combined with lidocaine spray applied to the posterior pharynx.6,8,9 Introduce 3 mL of 2% viscous lidocaine into the nostril and then have the patient snort the medication.

• Nebulized lidocaine—2.5 to 5 mL of 4% lidocaine nebulized before insertion via face mask.10

• Atomized lidocaine—1.5 mL of 4% lidocaine or two puffs of 10% lidocaine atomized to the nasal passage.6,11

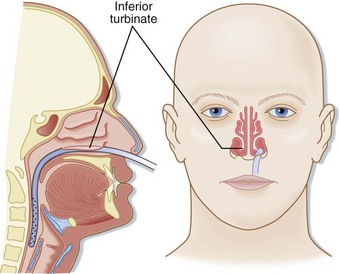

4 Insertion of the Tube

The tube is inserted into the naris along the floor of the nose inferior to the lower turbinates. The tube should be inserted at close to a 90-degree angle with the face and directed parallel to the floor of the nose (posteriorly), not cephalad (Fig. 46.2). Gentle pressure should be used to advance the tube past the nasopharynx and into the oropharynx. Once the tube is in the posterior pharynx, the patient is asked to swallow or take a sip of water to aid in smooth passage of the tube into the esophagus. The tube is then quickly advanced to the premeasured length to minimize discomfort. Care should be taken to not use excessive force when placing an NGT to avoid mucosal injury.

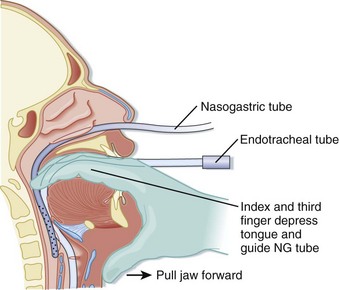

Alternative Approaches with Difficult Tube Insertions

Alternatively, digital placement of an NGT can be accomplished in a paralyzed, sedated, and intubated patient. The emergency physician places the second and third fingers in the posterior pharynx of the patient and depresses the tongue. The tube is passed through the nose into the posterior pharynx with the fingers in the pharynx to direct the tube into proper location (Fig. 46.3).2

Verifying Tube Placement

• Insufflation of air causing or resulting in borborygmi (gurgling) sounds heard over the epigastrium verifies that the tube is in the stomach.

• Aspiration of gastric fluid; a pH less than 4 is correlated with a 95% likelihood that the tip of the tube is in the stomach.

• In a conscious patient, normal clear speech without coughing is suggestive of proper tube placement.12

Complications

Placement of an NGT has a complication rate between 0.5% and 1.5%. Common complications are as follows13:

• Tracheal or bronchial placement

• Esophageal or pharyngeal perforation

• Esophageal obstruction or rupture

• Gastrothorax and tension gastrothorax

• Pulmonary aspiration; the NGT may induce a hypersalivation response, a depressed cough reflex, or mechanical or physiologic impairment of the glottis14–16

Transabdominal Feeding Tubes

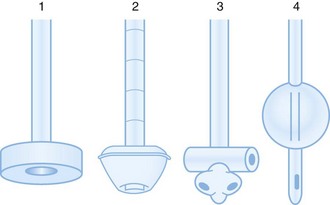

Feeding tubes are placed to provide long-term nutritional support. They are classified both by the location of their terminal lumen and by the method of placement. Gastrostomy tubes have a terminal lumen located within the stomach and are now typically placed via a percutaneous endoscopic technique; they are thus called PEG (percutaneous, endoscopically placed gastrostomy) tubes (Fig. 46.4). Several manufacturers make various types of PEG tubes. The other most frequently encountered feeding tube is a J tube, or jejunostomy tube. Such tubes are longer, smaller-caliber tubes that terminate in the jejunum. Unlike a gastrostomy tube, a J tube does not have an inflated balloon on its terminal end.

Fig. 46.4 Types of gastrostomy tubes.

(From Samuels LE. Nasogastric and feeding tube placement. In: Roberts JR, Hedges JR, editors. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004. pp. 794-816.)

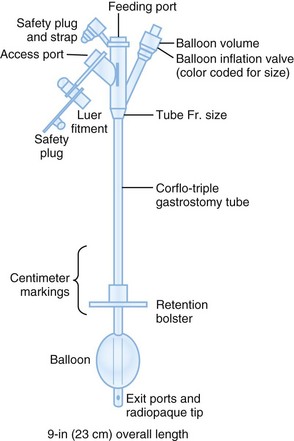

The classic open surgical gastrostomy procedure is less commonly performed than the percutaneous techniques. Percutaneous tubes can be placed by a gastroenterologist via endoscopy or by a radiologist via fluoroscopy. Fewer complications are seen with radiographically placed tubes than with tubes placed either by an open technique or endoscopically (Fig. 46.5).17,18

Fig. 46.5 User-friendly gastrostomy tube from CORPAK MedSystems (Wheeling, IL).

(From Samuels LE. Nasogastric and feeding tube placement. In: Roberts JR, Hedges JR, editors. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004. pp. 794-816.)

Major Complications of Transabdominal Feeding Tubes

Serious complications seen with transabdominal feeding tubes almost always require hospitalization and gastroenterology or surgery consultation (or both). Intestinal complications include obstruction, perforations, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, volvulus, and gastric outlet obstruction. Serious infections include bacteremia, pulmonary aspiration, sepsis, peritonitis, advanced local cellulitis, and necrotizing fasciitis.19–22 Other complications of gastrostomy tubes are prolapse with and without intestinal obstruction, extraluminal position of the tube, and fistula formation.23 Patients may also demonstrate minor and major electrolyte abnormalities and, rarely, pneumothorax.

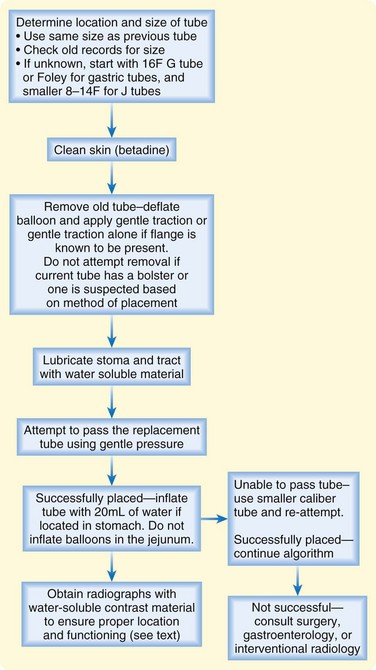

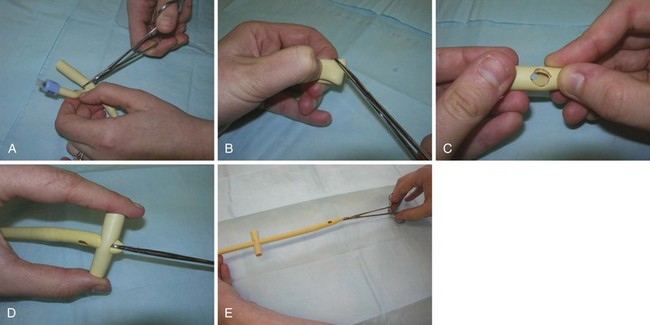

Replacing a Tube

Transabdominal feeding tubes must be replaced (Fig. 46.6) for many reasons, including expulsion, malfunction, leakage, tube deterioration resulting in cracks or fissures, and aneurysmal dilations of the tube. It is important that a patient’s tube be correctly identified with respect to type, size, and manufacturer before an attempt at replacement. A dislodged tube should be replaced as quickly as possible to maintain patency of the feeding tube tract. When replacing a feeding a tube it is important to clarify whether the terminal end was in the stomach versus the jejunum. After placement, the anchoring balloon in the replacement tube should be inflated in G tubes but never in J tubes.

Removing a Nonfunctional Tube

As an alternative method, the tube is lifted off the abdominal wall skin to allow the tube to be cut as close to the skin as possible. The internal component is then pushed into the GI tract so that it is free to pass through the intestines and be eliminated rectally. Most internal components pass within 2 weeks. There have, however, been reported cases of intestinal obstruction, perforation, and rarely death with this method.24,25 The internal component is less likely to pass without complications in children than in adults.26 If this technique is used, reliable patient follow-up is needed for serial abdominal radiographs. Radiographs should be taken within 1 week to monitor the progress of the component through the GI tract. If the internal component has not passed within 1 to 2 weeks, impaction has probably occurred, and endoscopic removal should be considered. Primary endoscopic removal is also advised in patients with intestinal obstruction, pseudoobstruction, pyloric stenosis, intestinal stricture, history of irradiation, and inflammatory bowel disease.27

Foley Catheters Versus Commercial Feeding Tube Products as Replacements

Both commercially available feeding tubes and Foley catheters can be used to replace a dislodged feeding tube. Commercial feeding tubes are more expensive than Foley catheters. Studies have found that a silicone Foley catheter with a retention disk and ring has the same efficacy and complication rate as a commercially available replacement gastrostomy tube. The retention disk and ring are used to prevent distal migration of the tube into the GI tract.28 However, many institutions do not stock silicone Foley catheters.

Foley Catheters Used as Replacement Feeding Tubes

A few simple modifications to a standard Foley catheter can maximize its longevity as a feeding tube, as well as reduce the chance of complications. When using a Foley catheter to replace a feeding tube, an external bolster, or anchor, is fashioned to prevent ingress of the tube into the ostomy and distal migration into the GI tract. An external bolster may be constructed by cutting a 3-cm section from a large rubber catheter. The outer bolster should be secured approximately 1 cm from the skin to prevent trapping of moisture and maceration.29 Its construction is as follows:

1. Cut a 3-cm section from the proximal segment of a Foley catheter to be used as a bolster, the end without the balloon. A silicone catheter is preferred over a latex one (Fig. 46.7, A).

2. Fold this segment in half and make a diagonal cut on each side of the fold to create a diamond-shaped opening in the middle of each side of the 3-cm segment of tubing. Cut the holes slightly smaller than the tube to be inserted and used as the feeding tube to ensure a snug fit of the bolster on the replacement tube (see Fig. 46.7, B and C).

3. Insert a hemostat through the two holes created in the bolster.

4. Grab the proximal end of the replacement tube with the hemostat and pull the tube through the bolster (see Fig. 46.7, D).

5. Advance the bolster to its proper location about 1 cm above the skin of the abdomen (see Fig. 46.7, E).28,30

Verifying Tube Location

No standard method for verifying tube placement has been established. The safest and best practice is to obtain radiographic confirmation when a feeding tube is replaced.31 Radiographic confirmation should be obtained in the following circumstances:

• With replacement of a recently placed feeding tube (less than 3 months) because the tract may not be mature

• When tube replacement was difficult

• When gastric material cannot be aspirated after placement

• When the patient is unable to communicate about symptoms such as pain with tube placement and use

Recently, two newer verification techniques have been described in small studies. The first uses air insufflation through the replacement tube to verify proper placement. Once the tube is replaced, a total of 240 mL of air is insufflated through the tube with a 60-mL syringe. The tube is considered properly replaced if it can be seen clearly within an air-distended stomach on a plain radiograph.32 The second technique was described in a small study with 10 subjects. Ultrasound was used to visualize the new tube as it was placed in the established tract. After insertion, color Doppler was applied over the catheter tip while it was gently oscillated to enhance visualization11 (Fig. 46.8).

Clogged Feeding Tubes

If a feeding tube is clogged by debris, the following approaches can be used to unclog the tube:

• Milk the external part of the tube backward in an attempt to expel the debris.

• Irrigate with small aliquots of carbonated beverages.

• Irrigate with small aliquots of warm water at high pressure; use a small syringe (5 to 10 mL) with manual injection.

Instrumentation of the tube with either a Fogarty arterial embolectomy catheter or a nasal foreign body catheter can also be attempted. The length of the feeding tube external to the abdomen should be measured and the Fogarty catheter inserted only to this length. An instrument should never be inserted past the abdominal wall skin. The balloon on the catheter can be inflated in the tube if an obstruction is encountered and then further advanced to probe the entire length of the external tube. The catheter should not be withdrawn with the balloon inflated because this action might cause removal of the feeding tube. In a 10 French (10F) or 12F tube, a No. 4 embolectomy catheter should be used; a 14F tube requires a No. 5 embolectomy catheter.33

Gastroesophageal Balloon Tamponade

Procedure

The following equipment is needed:

• Gloves and personal protective equipment

• NGT if the tamponade tube does not have an esophageal aspiration lumen

• Manometer or sphygmomanometer

• Suction device with connectors

• Tubing to connect to suction

1. If needed, intubate the patient before placement of the tube.

2. Check the balloons for patency and leaks before use: use 100-mL increments of air to inflate the gastric balloon, and check the pressure with a sphygmomanometer after each increment. These pressure measurements should be recorded for each 100-mL increment of air and will be used to compare pressure readings once the tube has been inserted (step 12). The pressure in the gastric balloon should not increase more than 15 mm Hg with insufflation of each 100 mL of air.

3. If an NGT is to be inserted, tie a suture around it and the GEBT tube to secure them together. The tip of the NGT should be located 3 to 4 cm proximal to the esophageal balloon.

4. Lubricate the tube or tubes with a water-soluble lubricant.

5. Position the patient either upright angled at 45 degrees or in the left lateral decubitus position.

6. Anesthetize the posterior pharynx or nasopharynx with topical anesthetic spray or nebulized lidocaine (or both; see previous discussion on NGT insertion).

7. Place an NGT and evacuate the stomach before placing a GEBT tube to decrease the chance of emesis and aspiration. Once the gastric contents have been evacuated, remove the NGT.

8. Deflate all balloons and either clamp the ends of the tubes or place plugs in each lumen if provided by the manufacturer.

9. Pass the tube to a minimum level of 50 cm as marked on the tube.

10. Connect suction to the gastric and esophageal lumens to check for contents and to decrease the likelihood of aspiration.

11. Confirm proper tube placement with radiographs even if gastric contents or blood is evacuated. The tip of the tube or balloon should be located below the diaphragm if properly placed.

12. Remove the clamps or plugs and inflate the gastric balloon slowly with 100-mL increments of air. Check the pressure of the gastric balloon after each injection; with each 100 mL of air insufflated, the pressure should not be more than 15 mm Hg higher than the pressure measurements previously obtained for the same volume of air (step 2). If the pressure rises by more than 15 mm Hg, the balloon may be located in the esophagus and not in the stomach. If this occurs, deflate the balloon and obtain another radiograph to ensure proper tube location before resuming air insufflation. Generally, 400 to 500 mL of air must be insufflated to obtain the proper pressure; check the manufacturer’s recommendation for the tube being used.

13. Once proper pressure is obtained, clamp or plug the lumens of the gastric balloon and the air inlet.

14. Gently pull back on the GEBT tube until it snugs up against the diaphragm and applies pressure at the gastroesophageal junction.

15. Secure the GEBT tube to the traction device to be used while applying a small amount of tension to the GEBT tube to keep constant pressure on the lower esophageal sphincter. The traction devices may be an orthopedic trapeze apparatus or another device provided by the manufacturer.

16. If the tube was passed nasally, place the sponge rubber cuffs provided by the manufacturer into each nostril or pad the nostrils with gauze to prevent pressure ulcers.

17. Once the tube is properly placed and secured, lavage the stomach with room-temperature water to assess for active bleeding. Attach the gastric lumen to high-pressure, intermittent suction.

18. If blood continues to be aspirated from the gastric lumen, the esophageal balloon can be inflated to a minimum pressure level to control the bleeding or to the maximum pressure advised by the manufacturer (typically 30 to 45 mm Hg). Clamp or plug the lumen of the esophageal balloon once a desired pressure level is obtained.

19. Frequent manometer readings of the esophageal balloon should be obtained to decrease the risk for complications.

20. If bleeding continues, the most likely source is gastric; tension on the gastric balloon may be increased gradually to help control the bleeding.

21. Obtain radiographs any time that the position of the tube comes into question.

22. Once the bleeding is controlled, attempts should be made to decrease the pressure in the esophageal balloon by increments of 5 mm Hg every 3 hours until a pressure of 25 mm Hg is reached (or as recommended by the manufacturer). Typically, a pressure of 25 mm Hg can be maintained for 12 to 24 hours if the bleeding is controlled.

23. If the esophageal balloon requires inflation at pressures greater than 30 mm Hg, the balloon should be deflated every 6 hours for 5-minute intervals to prevent complications such as mucosal ischemia and necrosis.

24. To prevent vomiting and aspiration, the esophagus must be emptied continuously even if the esophageal balloon is not inflated. The gastric balloon will preclude passage of secretions into the stomach. Aspirate with either an esophageal aspiration port in a Minnesota tube or an NGT with its tip located in the esophagus next to the GEBT tube. The volume of oral and esophageal secretions can total up to 1500 mL/day.

25. Once the GEBT tube is properly inserted and bleeding has been controlled, the tube should not be disturbed for 12 to 24 hours.

26. If bleeding cannot be controlled, further therapies are indicated, such as emergency surgery, endoscopic interventions, or angiographic embolization.

Complications

Use of the GEBT tube is associated with many minor and major complications (Box 46.2). Such tubes should be used only when life-threatening bleeding occurs and other available modalities have failed. Approximately 8% to 16% of patients treated with GEBT tubes have a major complication, with reported mortality rates of 3%.34–36

Jacobson G, Brokish PA, Wrenn K. Percutaneous feeding tube replacement in the ED—are confirmatory x-rays necessary? Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:519–524.

Kadakia SC, Cassaday M, Shaffer RT. Comparison of Foley catheter as a replacement gastrostomy tube with commercial replacement gastrostomy tube: a prospective randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:188–193.

Kuo YW, Yen M, Fetzer S, et al. Reducing the pain of nasogastric tube intubation with nebulized and atomized lidocaine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:613–620.

McCormick PA, Burroughs AK, McIntyre N. How to insert a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube. Br J Hosp Med. 1990;43:274–277.

1 Ikard RW, Federspiel CF. A comparison of Levin and sump nasogastric tubes for postoperative gastrointestinal decompression. Am Surg. 1987;53:50–53.

2 McCormick PA, Burroughs AK, McIntyre N. How to insert a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube. Br J Hosp Med. 1990;43:274–277.

3 Hanson RL. Predictive criteria for length of nasogastric tube insertion for tube feeding. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1979;3:160–163.

4 Singer AJ, Richman PB, et al. Comparison of patient and practitioner assessments of pain from commonly performed emergency department procedures. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:652–658.

5 Spektor M, Kaplan J, Kelley J, et al. Nebulized or sprayed lidocaine as anesthesia for nasogastric intubations. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:406–408.

6 Ducharme J, Matheson K. What is the best topical anesthetic for nasogastric insertion? A comparison of lidocaine gel, lidocaine spray, and atomized cocaine. J Emerg Nurs. 2003;29:427–430.

7 Kuo YW, Yen M, Fetzer S, et al. Reducing the pain of nasogastric tube intubation with nebulized and atomized lidocaine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:613–620.

8 Middleton RM, Shah A, Kirkpatrick MB. Topical nasal anesthesia for flexible bronchoscopy. A comparison of four methods in normal subjects and in patients undergoing transnasal bronchoscopy. Chest. 1991;99:1093–1096.

9 Webb AR, Woodhead MA, Dalton HR, et al. Topical nasal anaesthesia for fibreoptic bronchoscopy: patients’ preference for lignocaine gel. Thorax. 1989;44:674–675.

10 Cullen L, Taylor D, Taylor S, et al. Nebulized lidocaine decreases the discomfort of nasogastric tube insertion: a randomized, double-blind trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:131–137.

11 Wu TS, Leech SJ, Rosenberg M, et al. Ultrasound can accurately guide gastrostomy tube replacement and confirm proper tube placement at the bedside. J Emerg Med. 2009;36:280–284.

12 Metheny N, Reed L, Wiersema L, et al. Effectiveness of pH measurements in predicting feeding tube placement: an update. Nurs Res. 1993;42:324–331.

13 Bankier AA, Wiesmayr MN, Henk C, et al. Radiographic detection of intrabronchial malpositions of nasogastric tubes and subsequent complications in intensive care unit patients. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:406–410.

14 Alessi DM, Berci G. Aspiration and nasogastric intubation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;94:486–489.

15 Roubenoff R, Ravich WJ. Pneumothorax due to nasogastric feeding tubes. Report of four cases, review of the literature, and recommendations for prevention. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:184–188.

16 Slater RG. Tension gastrothorax complicating acute traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. J Emerg Med. 1992;10:25–30.

17 Wollman B, D’Agostino HB, Walus-Wigle JR, et al. Radiologic, endoscopic, and surgical gastrostomy: an institutional evaluation and meta-analysis of the literature. Radiology. 1995;197:699–704.

18 Wollman B, D’Agostino HB. Percutaneous radiologic and endoscopic gastrostomy: a 3-year institutional analysis of procedure performance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1551–1553.

19 Cataldi-Betcher EL, Seltzer MH, Slocum BA, et al. Complications occurring during enteral nutrition support: a prospective study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1983;7:546–552.

20 Ponsky JL, Gauderer MW, Stellato TA, et al. Percutaneous approaches to enteral alimentation. Am J Surg. 1985;149:102–105.

21 Rombeau JL, Twomey PL, McLean GK, et al. Experience with a new gastrostomy-jejunal feeding tube. Surgery. 1983;93:574–578.

22 Torosian MH, Rombeau JL. Feeding by tube enterostomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1980;150:918–927.

23 Wolf EL, Frager D, Beneventano TC. Radiologic demonstration of important gastrostomy tube complications. Gastrointest Radiol. 1986;11:20–26.

24 Coventry BJ, Karatassas A, Gower L, et al. Intestinal passage of the PEG end-piece: is it safe? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;9:311–313.

25 Korula J, Harma C. A simple and inexpensive method of removal or replacement of gastrostomy tubes. JAMA. 1991;265:1426–1428.

26 Yaseen M, Steele MI, Grunow JE. Nonendoscopic removal of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes: morbidity and mortality in children. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:235–238.

27 Tintinalli JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS. Emergency medicine: a comprehensive study guide, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004.

28 Kadakia SC, Cassaday M, Shaffer RT. Comparison of Foley catheter as a replacement gastrostomy tube with commercial replacement gastrostomy tube: a prospective randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:188–193.

29 Strodel W. Complications of percutaneous gastrostomy. In: Ponsky JL, ed. Techniques of percutaneous gastrostomy. New York: Igaku-Shoin, 1988.

30 Kadakia SC, Cassaday M, Shaffer RT. Prospective evaluation of Foley catheter as a replacement gastrostomy tube. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1594–1597.

31 Jacobson G, Brokish PA, Wrenn K. Percutaneous feeding tube replacement in the ED—are confirmatory x-rays necessary? Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:519–524.

32 Burke DT, El Shami A, Heinle E, et al. Comparison of gastrostomy tube replacement verification using air insufflation versus Gastrografin. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:1530–1533.

33 Bentz ML, Tollett CA, Dempsey DT. Obstructed feeding jejunostomy tube: a new method of salvage. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1988;12:417–418.

34 Bauer JJ, Kreel I, Kark AE. The use of the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube for immediate control of bleeding esophageal varices. Ann Surg. 1974;179:273–277.

35 Hermann RE, Traul D. Experience with the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube for bleeding esophageal varices. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1970;130:879–885.

36 Panes J, Teres J, Bosch J, et al. Efficacy of balloon tamponade in treatment of bleeding gastric and esophageal varices. Results in 151 consecutive episodes. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:454–459.