Gastrointestinal Clinical Assessment and Diagnostic Procedures

Clinical Assessment

A thorough clinical assessment of the patient with GI dysfunction is imperative for the early identification and treatment of GI disorders. The completed assessment serves as the foundation for developing the management plan for the patient. The assessment process can be brief or can involve a detailed history and examination, depending on the nature and immediacy of the patient’s situation.1,2

History

The initial presentation of the patient determines the rapidity and direction of the interview. For a patient in acute distress, the history should be curtailed to a few questions about the patient’s chief complaint and the precipitating events. For a patient in no obvious distress, the history should focus on current symptoms, the patient’s medical history, and the family’s history. Specific items regarding each of these areas are outlined in Box 29-1, Data Collection.3,4

Physical Examination

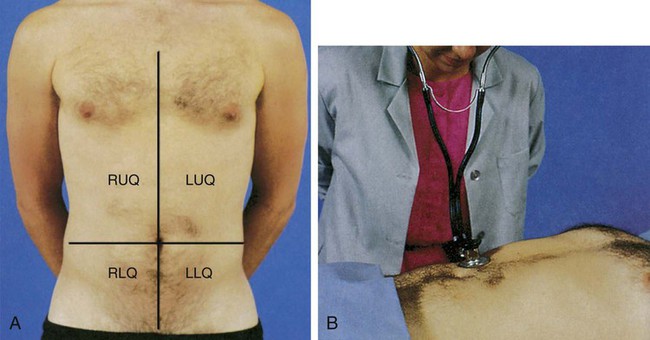

The physical examination helps establish baseline data about the physical dimensions of the patient’s situation.3 The abdomen is divided into four quadrants (left upper, right upper, left lower, and right lower), with the umbilicus as the middle point, to specify the location of examination findings (Fig. 29-1 and Box 29-2). The assessment should proceed when the patient is as comfortable as possible and in the supine position; however, the position may need readjustment if it elicits pain. To prevent stimulation of GI activity, the order for the assessment should be changed to inspection, auscultation, percussion, and palpation.4

Inspection

Observe the skin for pigmentation, lesions, striae, scars, petechiae, signs of dehydration, and venous pattern. Pigmentation may vary considerably and still be within normal limits because of race and ethnic background, although the abdomen usually is of a lighter color than other exposed areas of the skin. Abnormal findings include jaundice, skin lesions, and a tense and glistening appearance of the skin. Old striae (stretch marks) usually are silver, whereas pinkish purple striae may indicate Cushing syndrome.4 A bluish discoloration of the umbilicus (Cullen sign) and of the flank (Grey-Turner sign) indicates retroperitoneal bleeding.1

Observe the abdomen for contour, noting whether it is flat, slightly concave, or slightly round; observe for symmetry and for movement. Marked distention is an abnormal finding. In particular, ascites may cause generalized distention and bulging flanks. Asymmetric distention may indicate organ enlargement or a mass. Peristaltic waves should not be visible except in very thin patients. In the case of intestinal obstruction, hyperactive peristaltic waves may be observed. Pulsation in the epigastric area is often a normal finding, but increased pulsation may indicate an aortic aneurysm. Symmetric movement of the abdomen with respirations is usually seen in men.4,5

Auscultation

Auscultation of the abdomen provides clinical data regarding the status of the bowel’s motility. Initially, listen with the diaphragm of the stethoscope below and to the right of the umbilicus. The examination proceeds methodically through all four quadrants, lifting and then replacing the diaphragm of the stethoscope lightly against the abdomen (see Fig. 29-1). Normal bowel sounds include high-pitched, gurgling sounds that occur approximately every 5 to 15 seconds or at a rate of 5 to 34 times per minute. Colonic sounds are low pitched and have a rumbling quality. A venous hum may be audible sometimes.6 Table 29-1 provides a list of abnormal abdominal sounds.

TABLE 29-1

| SOUND | CAUSE |

| Hyperactive bowel sounds (borborygmi), loud and prolonged | Hunger, gastroenteritis, or early intestinal obstruction |

| High-pitched, tinkling sounds | Intestinal air and fluid under pressure; characteristic of early intestinal obstruction |

| Decreased (hypoactive) bowel sounds | Possible peritonitis or ileus |

| Infrequent and abnormally faint sounds | |

| Absence of bowel sounds (confirmed only after auscultation of all four quadrants and continuous auscultation for 5 minutes) | Temporary loss of intestinal motility, as occurs with complete ileus |

| Friction rubs | Pathologic conditions such as tumors or infection that cause inflammation of organ’s peritoneal covering |

| High-pitched sounds heard over liver and spleen (RUQ and LUQ), synchronous with respiration | |

| Bruits | Abnormality of blood flow (requires additional evaluation to determine specific disorder) |

| Audible swishing sounds that may be heard over aortic, iliac, renal, and femoral arteries | |

| Venous hum | Increased collateral circulation between portal and systemic venous systems |

| Low-pitched, continuous sound |

LUQ, Left upper quadrant; RUQ, right upper quadrant.

From Doughty DB, Jackson DB. Gastrointestinal Disorders. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993.

Abnormal findings include the absence of bowel sounds throughout a 5-minute period, extremely soft and widely separated sounds, and increased sounds with a high-pitched, loud rushing sound (peristaltic rush). Absent bowel sounds may result from inflammation, ileus, electrolyte disturbances, and ischemia. Bowels sounds may be increased with diarrhea and early intestinal obstruction.6

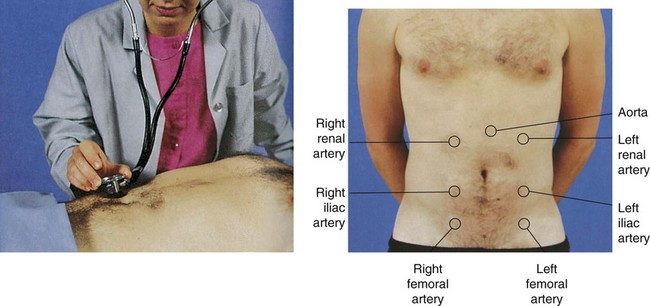

The abdomen should be auscultated for the presence of bruits, using the bell of the stethoscope (Fig. 29-2). Bruits are created by turbulent flow over a partially obstructed artery and are always considered an abnormal finding. The aorta, the right and left renal arteries, and the iliac arteries should be auscultated.5,6

Percussion

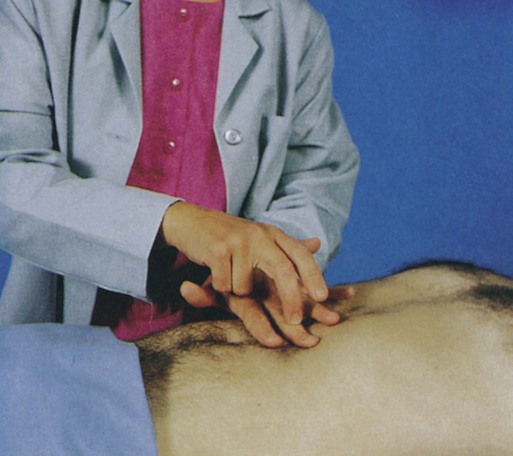

Percussion is used to elicit information about deep organs such as the liver, spleen, and pancreas (Fig. 29-3). Because the abdomen is a sensitive area, muscle tension may interfere with this part of the assessment. Percussion often helps relax tense muscles, and it is performed before palpation. Percussion in the absence of disease helps delineate the position and size of the liver and spleen, and it assists in the detection of fluid, gaseous distention, and masses in the abdomen.5

Percussion should proceed systematically and lightly in all four quadrants. Normal findings include tympany over the empty stomach, tympany or hyper-resonance over the intestine, and dullness over the liver and spleen. Abnormal areas of dullness may indicate an underlying mass. Solid masses, enlarged organs, and a distended bladder also produce areas of dullness. Dullness over both flanks may indicate ascites and necessitates further assessment.6

Palpation

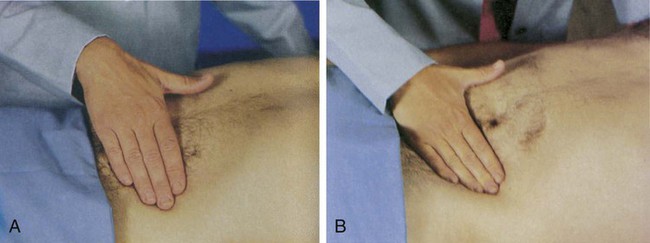

Palpation is the assessment technique most useful in detecting abdominal pathologic conditions. Light and deep palpation of each organ and quadrant should be completed. Light palpation, which has a palpation depth of approximately 1 cm, assesses to the depth of the skin and fascia (Fig. 29-4A). Deep palpation assesses the rectus abdominis muscle and is performed bimanually to a depth of 4 to 5 cm (see Fig. 29-4B). Deep palpation is most helpful in detecting abdominal masses. Areas in which the patient complains of tenderness should be palpated last.6

Normal findings include no areas of tenderness or pain, no masses, and no hardened areas. Persistent involuntary guarding may indicate peritoneal inflammation, particularly if it continues even after relaxation techniques are used. Rebound tenderness, in which pain increases with quick release of a palpated area, indicates an inflamed peritoneum.4

Assessment Findings for Common Disorders

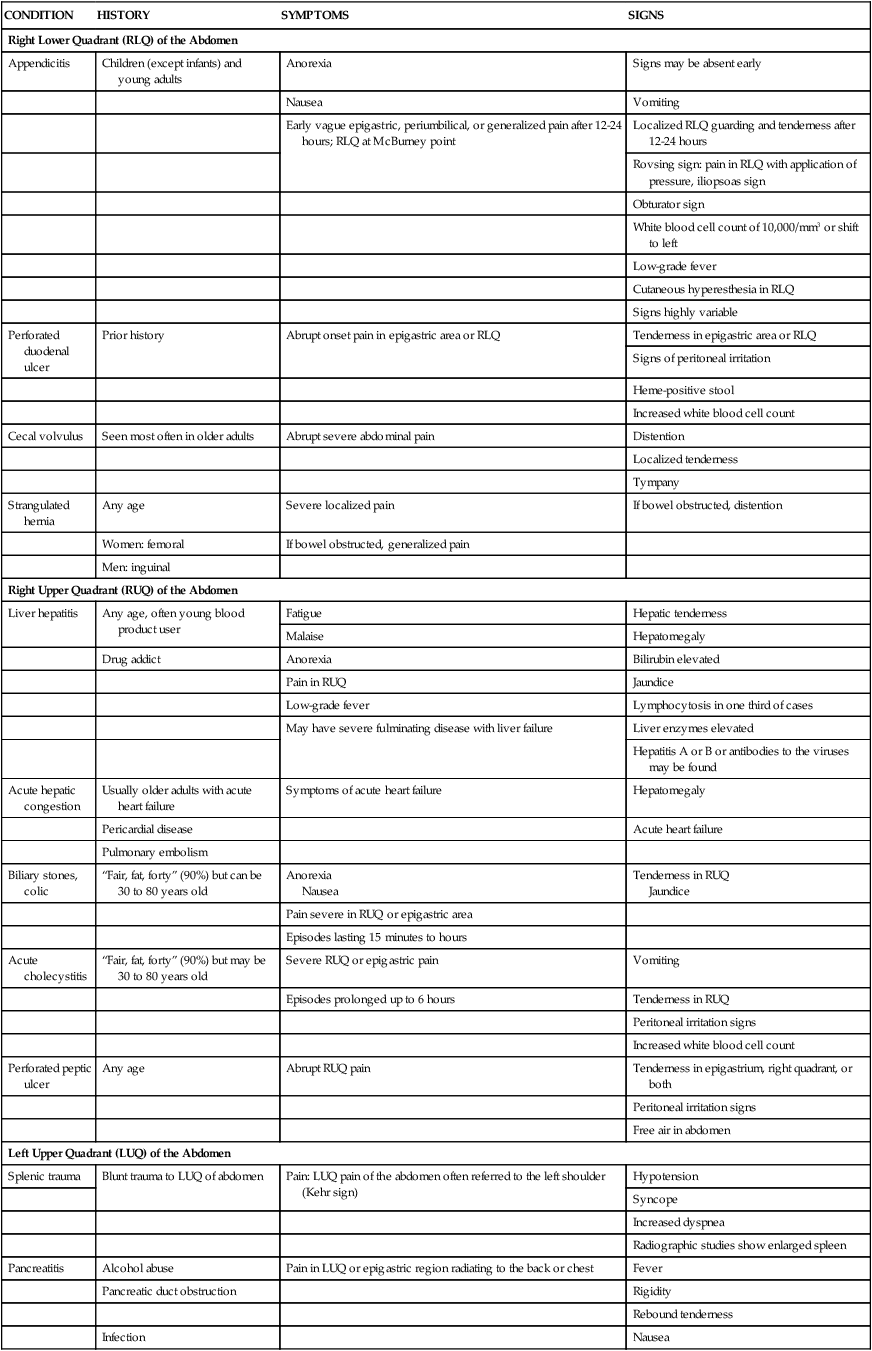

Table 29-2 presents a variety of common GI disorders and their associated assessment findings.

TABLE 29-2

ASSESSMENT FINDINGS OF COMMON GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS

| CONDITION | HISTORY | SYMPTOMS | SIGNS |

| Right Lower Quadrant (RLQ) of the Abdomen | |||

| Appendicitis | Children (except infants) and young adults | Anorexia | Signs may be absent early |

| Nausea | Vomiting | ||

| Early vague epigastric, periumbilical, or generalized pain after 12-24 hours; RLQ at McBurney point | Localized RLQ guarding and tenderness after 12-24 hours | ||

| Rovsing sign: pain in RLQ with application of pressure, iliopsoas sign | |||

| Obturator sign | |||

| White blood cell count of 10,000/mm3 or shift to left | |||

| Low-grade fever | |||

| Cutaneous hyperesthesia in RLQ | |||

| Signs highly variable | |||

| Perforated duodenal ulcer | Prior history | Abrupt onset pain in epigastric area or RLQ | Tenderness in epigastric area or RLQ |

| Signs of peritoneal irritation | |||

| Heme-positive stool | |||

| Increased white blood cell count | |||

| Cecal volvulus | Seen most often in older adults | Abrupt severe abdominal pain | Distention |

| Localized tenderness | |||

| Tympany | |||

| Strangulated hernia | Any age | Severe localized pain | If bowel obstructed, distention |

| Women: femoral | If bowel obstructed, generalized pain | ||

| Men: inguinal | |||

| Right Upper Quadrant (RUQ) of the Abdomen | |||

| Liver hepatitis | Any age, often young blood product user | Fatigue | Hepatic tenderness |

| Malaise | Hepatomegaly | ||

| Drug addict | Anorexia | Bilirubin elevated | |

| Pain in RUQ | Jaundice | ||

| Low-grade fever | Lymphocytosis in one third of cases | ||

| May have severe fulminating disease with liver failure | Liver enzymes elevated | ||

| Hepatitis A or B or antibodies to the viruses may be found | |||

| Acute hepatic congestion | Usually older adults with acute heart failure | Symptoms of acute heart failure | Hepatomegaly |

| Pericardial disease | Acute heart failure | ||

| Pulmonary embolism | |||

| Biliary stones, colic | “Fair, fat, forty” (90%) but can be 30 to 80 years old | Anorexia Nausea |

Tenderness in RUQ Jaundice |

| Pain severe in RUQ or epigastric area | |||

| Episodes lasting 15 minutes to hours | |||

| Acute cholecystitis | “Fair, fat, forty” (90%) but may be 30 to 80 years old | Severe RUQ or epigastric pain | Vomiting |

| Episodes prolonged up to 6 hours | Tenderness in RUQ | ||

| Peritoneal irritation signs | |||

| Increased white blood cell count | |||

| Perforated peptic ulcer | Any age | Abrupt RUQ pain | Tenderness in epigastrium, right quadrant, or both |

| Peritoneal irritation signs | |||

| Free air in abdomen | |||

| Left Upper Quadrant (LUQ) of the Abdomen | |||

| Splenic trauma | Blunt trauma to LUQ of abdomen | Pain: LUQ pain of the abdomen often referred to the left shoulder (Kehr sign) | Hypotension |

| Syncope | |||

| Increased dyspnea | |||

| Radiographic studies show enlarged spleen | |||

| Pancreatitis | Alcohol abuse | Pain in LUQ or epigastric region radiating to the back or chest | Fever |

| Pancreatic duct obstruction | Rigidity | ||

| Rebound tenderness | |||

| Infection | Nausea | ||

| Cholecystitis | Vomiting | ||

| Jaundice | |||

| Cullen sign | |||

| Turner sign | |||

| Abdominal distention | |||

| Diminished bowel sounds | |||

| Pyloric obstruction | Duodenal ulcer | Weight loss | Increasing dullness in LUQ |

| Gastric upset | Visible peristaltic waves in epigastric region | ||

| Vomiting | |||

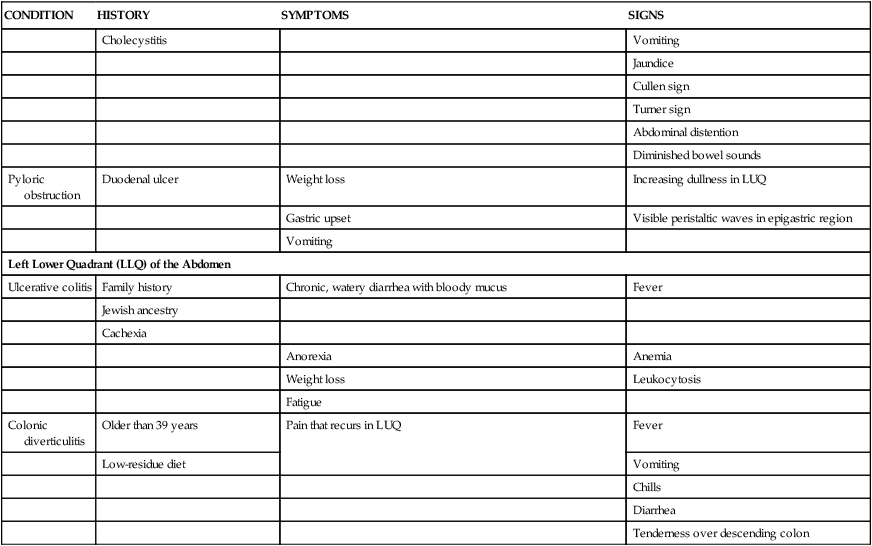

| Left Lower Quadrant (LLQ) of the Abdomen | |||

| Ulcerative colitis | Family history | Chronic, watery diarrhea with bloody mucus | Fever |

| Jewish ancestry | |||

| Cachexia | |||

| Anorexia | Anemia | ||

| Weight loss | Leukocytosis | ||

| Fatigue | |||

| Colonic diverticulitis | Older than 39 years | Pain that recurs in LUQ | Fever |

| Low-residue diet | Vomiting | ||

| Chills | |||

| Diarrhea | |||

| Tenderness over descending colon | |||

Modified from Barkauskas V, et al. Health & Physical Assessment. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002.

Laboratory Studies

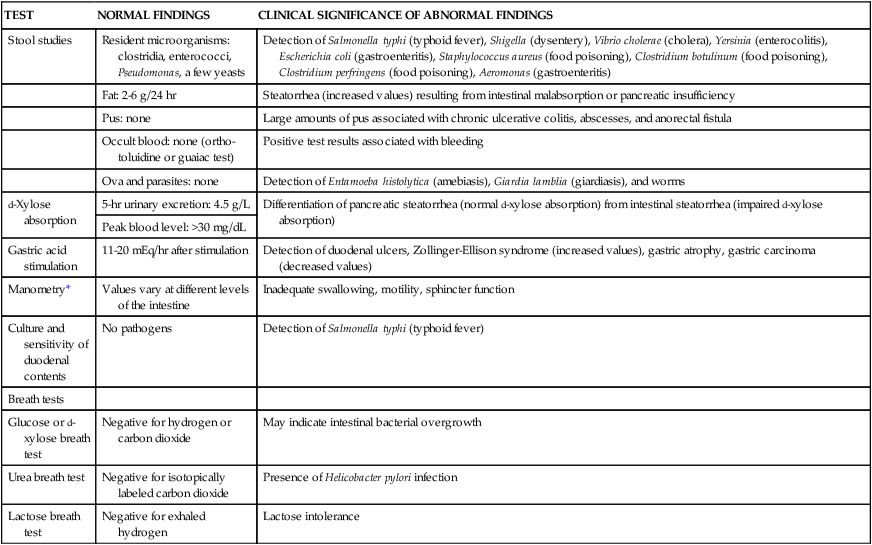

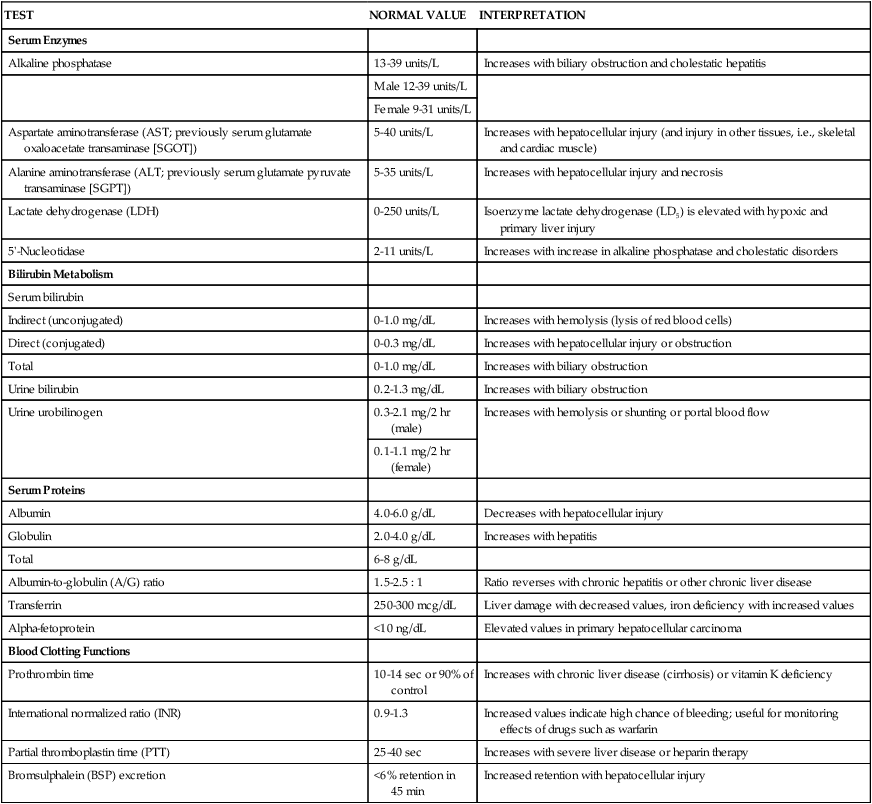

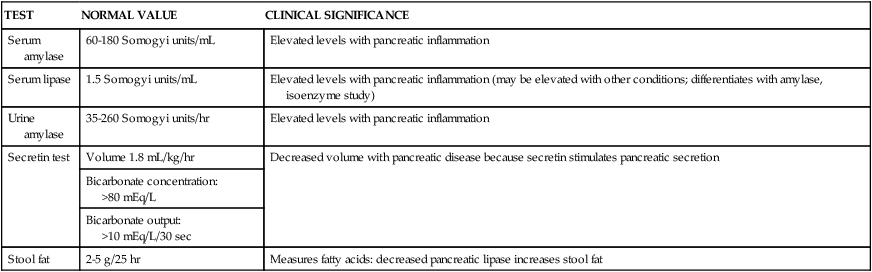

The value of various laboratory studies used to diagnose and treat diseases of the GI system has been emphasized often. However, no single study provides an overall picture of the various organs’ functional state, and no single value is predictive by itself. Laboratory studies used in the assessment of GI function, liver function, and pancreatic function are found in Tables 29-3, 29-4, and 29-5, respectively.

TABLE 29-3

SELECTED LABORATORY STUDIES OF GASTROINTESTINAL FUNCTION

| TEST | NORMAL FINDINGS | CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF ABNORMAL FINDINGS |

| Stool studies | Resident microorganisms: clostridia, enterococci, Pseudomonas, a few yeasts | Detection of Salmonella typhi (typhoid fever), Shigella (dysentery), Vibrio cholerae (cholera), Yersinia (enterocolitis), Escherichia coli (gastroenteritis), Staphylococcus aureus (food poisoning), Clostridium botulinum (food poisoning), Clostridium perfringens (food poisoning), Aeromonas (gastroenteritis) |

| Fat: 2-6 g/24 hr | Steatorrhea (increased values) resulting from intestinal malabsorption or pancreatic insufficiency | |

| Pus: none | Large amounts of pus associated with chronic ulcerative colitis, abscesses, and anorectal fistula | |

| Occult blood: none (ortho-toluidine or guaiac test) | Positive test results associated with bleeding | |

| Ova and parasites: none | Detection of Entamoeba histolytica (amebiasis), Giardia lamblia (giardiasis), and worms | |

| d-Xylose absorption | 5-hr urinary excretion: 4.5 g/L | Differentiation of pancreatic steatorrhea (normal d-xylose absorption) from intestinal steatorrhea (impaired d-xylose absorption) |

| Peak blood level: >30 mg/dL | ||

| Gastric acid stimulation | 11-20 mEq/hr after stimulation | Detection of duodenal ulcers, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (increased values), gastric atrophy, gastric carcinoma (decreased values) |

| Manometry* | Values vary at different levels of the intestine | Inadequate swallowing, motility, sphincter function |

| Culture and sensitivity of duodenal contents | No pathogens | Detection of Salmonella typhi (typhoid fever) |

| Breath tests | ||

| Glucose or d-xylose breath test | Negative for hydrogen or carbon dioxide | May indicate intestinal bacterial overgrowth |

| Urea breath test | Negative for isotopically labeled carbon dioxide | Presence of Helicobacter pylori infection |

| Lactose breath test | Negative for exhaled hydrogen | Lactose intolerance |

*Use of water-filled catheters connected to pressure transducers passed into the esophagus, stomach, colon, or rectum to evaluate contractility.

From McCance KL, Huether SE, eds. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2010.

TABLE 29-4

COMMON LABORATORY STUDIES OF LIVER FUNCTION

| TEST | NORMAL VALUE | INTERPRETATION |

| Serum Enzymes | ||

| Alkaline phosphatase | 13-39 units/L | Increases with biliary obstruction and cholestatic hepatitis |

| Male 12-39 units/L | ||

| Female 9-31 units/L | ||

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST; previously serum glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase [SGOT]) | 5-40 units/L | Increases with hepatocellular injury (and injury in other tissues, i.e., skeletal and cardiac muscle) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT; previously serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase [SGPT]) | 5-35 units/L | Increases with hepatocellular injury and necrosis |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | 0-250 units/L | Isoenzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LD5) is elevated with hypoxic and primary liver injury |

| 5′-Nucleotidase | 2-11 units/L | Increases with increase in alkaline phosphatase and cholestatic disorders |

| Bilirubin Metabolism | ||

| Serum bilirubin | ||

| Indirect (unconjugated) | 0-1.0 mg/dL | Increases with hemolysis (lysis of red blood cells) |

| Direct (conjugated) | 0-0.3 mg/dL | Increases with hepatocellular injury or obstruction |

| Total | 0-1.0 mg/dL | Increases with biliary obstruction |

| Urine bilirubin | 0.2-1.3 mg/dL | Increases with biliary obstruction |

| Urine urobilinogen | 0.3-2.1 mg/2 hr (male) | Increases with hemolysis or shunting or portal blood flow |

| 0.1-1.1 mg/2 hr (female) | ||

| Serum Proteins | ||

| Albumin | 4.0-6.0 g/dL | Decreases with hepatocellular injury |

| Globulin | 2.0-4.0 g/dL | Increases with hepatitis |

| Total | 6-8 g/dL | |

| Albumin-to-globulin (A/G) ratio | 1.5-2.5 : 1 | Ratio reverses with chronic hepatitis or other chronic liver disease |

| Transferrin | 250-300 mcg/dL | Liver damage with decreased values, iron deficiency with increased values |

| Alpha-fetoprotein | <10 ng/dL | Elevated values in primary hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Blood Clotting Functions | ||

| Prothrombin time | 10-14 sec or 90% of control | Increases with chronic liver disease (cirrhosis) or vitamin K deficiency |

| International normalized ratio (INR) | 0.9-1.3 | Increased values indicate high chance of bleeding; useful for monitoring effects of drugs such as warfarin |

| Partial thromboplastin time (PTT) | 25-40 sec | Increases with severe liver disease or heparin therapy |

| Bromsulphalein (BSP) excretion | <6% retention in 45 min | Increased retention with hepatocellular injury |

From McCance KL, Huether SE, eds. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2010.

TABLE 29-5

COMMON LABORATORY STUDIES OF PANCREATIC FUNCTION

| TEST | NORMAL VALUE | CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE |

| Serum amylase | 60-180 Somogyi units/mL | Elevated levels with pancreatic inflammation |

| Serum lipase | 1.5 Somogyi units/mL | Elevated levels with pancreatic inflammation (may be elevated with other conditions; differentiates with amylase, isoenzyme study) |

| Urine amylase | 35-260 Somogyi units/hr | Elevated levels with pancreatic inflammation |

| Secretin test | Volume 1.8 mL/kg/hr | Decreased volume with pancreatic disease because secretin stimulates pancreatic secretion |

| Bicarbonate concentration: >80 mEq/L | ||

| Bicarbonate output: >10 mEq/L/30 sec | ||

| Stool fat | 2-5 g/25 hr | Measures fatty acids: decreased pancreatic lipase increases stool fat |

From McCance KL, Huether SE, eds. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2010.

Diagnostic Procedures

Endoscopy

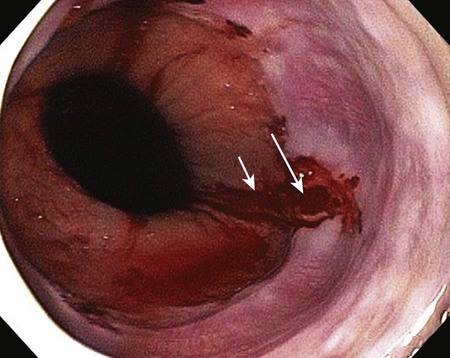

Available in several forms, fiberoptic endoscopy is a diagnostic procedure for the direct visualization and evaluation of the GI tract. Endoscopy can provide information about lesions, mucosal changes, obstructions, and motility dysfunction, and a biopsy specimen can be obtained during the procedure. The main difference between the various diagnostic forms is the length of the anatomic area that can be examined. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) permits viewing of the upper GI tract from the esophagus to the upper duodenum, and it is used to evaluate sources of upper GI bleeding (Fig. 29-5). Colonoscopy permits viewing of the lower GI tract from the rectum to the distal ileum, and it is used to evaluate sources of lower GI bleeding. Enteroscopy permits viewing of the small bowel beyond the ligament of Treitz, and it is used to evaluate sources of GI bleeding that have not been identified previously with EGD or colonoscopy. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) enables viewing of the biliary and pancreatic ducts, and it is used in the evaluation of pancreatitis. During this procedure, contrast is injected into the ducts through the endoscope, and radiographs are obtained.7 Endoscopy also provides therapeutic benefits for a variety of conditions, including GI bleeding.8

Nursing Management

The patient should take nothing by mouth (NPO) for 6 to 12 hours before endoscopy of the upper GI tract. The patient should receive a bowel preparation before endoscopy of the lower GI tract.7 In some cases, the procedure is performed at the patient’s bedside, particularly if the patient is actively bleeding and too unstable to be moved to the GI suite. Fiberoptic endoscopy may present risks for the patient. Although rare, potential complications include perforation of the GI tract, hemorrhage, aspiration, vasovagal stimulation, and oversedation.7 Signs of perforation include abdominal pain and distention, GI bleeding, and fever.9

Angiography

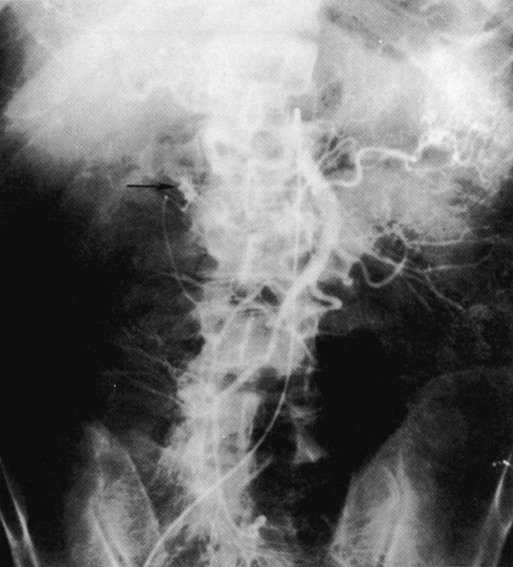

Angiography is used as a diagnostic and a therapeutic procedure. Diagnostically, it is used to evaluate the status of the GI circulation (Fig. 29-6).7 Therapeutically, it is used to achieve transcatheter control of GI bleeding.10 Angiography is used in the diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding only when endoscopy fails, and it is used to treat patients (approximately 15%) whose GI bleeding is not stopped with medical measures or endoscopic treatment.10 Angiography also is used to evaluate cirrhosis, portal hypertension, intestinal ischemia, and other vascular abnormalities.7

The radiologist cannulates the femoral artery with a needle and passes a guidewire through it into the aorta. The needle is removed, and an angiographic catheter is inserted over the guidewire. The catheter is advanced into the vessel supplying the portion of the GI tract that is being studied. After the catheter is in place, contrast medium is injected, and serial radiographs are obtained. If the procedure is undertaken to control bleeding, vasopressin (Pitressin Synthetic) or embolic material (Gelfoam) is injected after the site of the bleeding is located.10

Nursing Management

Complications include overt and covert bleeding at the femoral puncture site, neurovascular compromise of the affected leg, and sensitivity to the contrast medium. Before the procedure, the patient should be asked about any sensitivity to contrast. Postprocedural assessment involves monitoring vital signs, observing the injection site for bleeding, and assessing neurovascular integrity distal to the injection site every 15 minutes for the first 1 to 2 hours. Depending on how the puncture site is stabilized after the procedure, the patient may have to remain flat in bed for a specified length of time. Any evidence of bleeding or neurovascular impairment must be immediately reported to the physician.11

Plain Abdominal Series

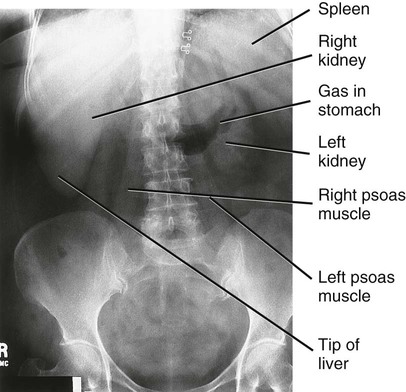

Although numerous radiologic studies are available to investigate GI dysfunction further, many of these studies are not performed on the critically ill patient. The radiologic study that is performed most often is the plain abdominal series (Fig. 29-7). An abdominal radiograph is useful in the diagnosis of a bowel obstruction and perforation.12

Air in the bowel serves as a contrast medium to aid in the visualization of the bowel. Gas patterns (the presence of gas inside or outside the bowel lumen and the distribution of gas in dilated and nondilated bowel) are best revealed by plain radiographs. Common radiologic signs of free air in the abdomen include the presence of air on both sides of the bowel wall and the presence of air in the right upper quadrant anterior to the liver.12 Table 29-6 lists common radiologic findings. Abdominal radiographs are used to verify nasogastric or feeding tube placement.

TABLE 29-6

| FINDING | APPEARANCE | ASSOCIATIONS |

| Pneumoperitoneum | Air seen under diaphragm on upright chest or overlying right lobe of liver on left lateral decubitus films | Most commonly associated with bowel perforation, although other causes exist |

| Peritoneal fluid | Medial displacement of colon separated from flank stripes by fluid density on flat plate | Ascites or hemorrhage |

| Adynamic ileus | Dilatation of entire intestinal tract, including stomach | Many causes, including trauma, infection (intra-abdominal and extra-abdominal), metabolic disease, and medications (e.g., narcotics) |

| Sentinel loop | Single distended loop of small bowel containing an air-fluid level | Represents localized ileus associated with localized inflammatory process such as cholecystitis, appendicitis, or pancreatitis |

| Small bowel obstruction | Dilated loops of small bowel (distinguished by valvulae conniventes, thin, transverse linear densities that extend completely across diameter of bowel) with air-fluid levels | Can be associated with other serious pathology such as incarcerated hernia, appendicitis, or mesenteric ischemia |

| Large bowel obstruction | Dilated loops, usually more peripheral in the abdomen (distinguished by haustra—short, thick indentations that do not completely cross-bowel and are less frequently spaced than valvulae conniventes) | Can be associated with diverticulitis and malignancy |

| Cecal volvulus | Usually found in middle or upper abdomen to the left; often kidney shaped | |

| Sigmoid volvulus | Dilated loop of colon arising from left side of pelvis and projecting obliquely upward toward right side of abdomen | |

| Early ischemic bowel findings | May resemble mechanical obstruction with dilated loops and air-fluid levels | |

| Later ischemic bowel findings | May resemble a dynamic ileus; thumbprinting (edema of bowel wall with convex indentations of lumen) and pneumatosis intestinalis (linear or mottled gas pattern in bowel wall) | |

| Gallbladder emergency findings | Ring of air outlining the gallbladder Air in biliary tree combined with signs of small bowel obstruction, possibly with visible calculus in pelvis |

Emphysematous cholecystitis Gallstone ileus |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) | Usually appears left of midline on supine film and anterior to spine in lateral projection; calcification in wall of aneurysm is variable | Ruptured or leaking AAA may reveal loss of psoas shadows or large soft tissue mass |

From Hendrickson M, Naparst TR. Abdominal surgical emergencies in the elderly. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:937.

Nursing Management

An abdominal radiographic series can be obtained at the patient’s bedside using a portable x-ray machine. The series includes two views of the abdomen: one in the supine position and one in the upright position. For patients unable to sit upright, a lateral decubitus radiograph may be obtained with the patient’s left side down. No special interventions are required before or after the procedure.11

Abdominal Ultrasound

Abdominal ultrasound is useful in evaluating the status of the gallbladder and biliary system, the liver, the spleen, and the pancreas. It plays a key role in the diagnosis of many acute abdominal conditions such as acute cholecystitis and biliary obstructions because it is sensitive in detecting obstructive lesions and ascites. Ultrasound is used to identify gallstones and hepatic abscesses, candidiasis, and hematomas. Intestinal gas, ascites, and extreme obesity can interfere with transmission of the sound waves and limit the usefulness of the procedure.13

The procedure uses sound waves to produce echoes that are converted into electrical energy and transferred to a screen for viewing. A transducer, which emits and receives sound waves, is moved slowly over the area of the abdomen being studied. Tissues with various densities produce different echoes, which translate into the different structures on the viewing screen.14

Nursing Management

An ultrasound scan can be obtained at the patient’s bedside using a portable scanning unit. Ultrasound is easily performed, noninvasive, and well tolerated even by critically ill patients. The procedure requires only that the patient lie still for 20 to 30 minutes. No special interventions are required before or after the procedure.11

Computed Tomography of the Abdomen

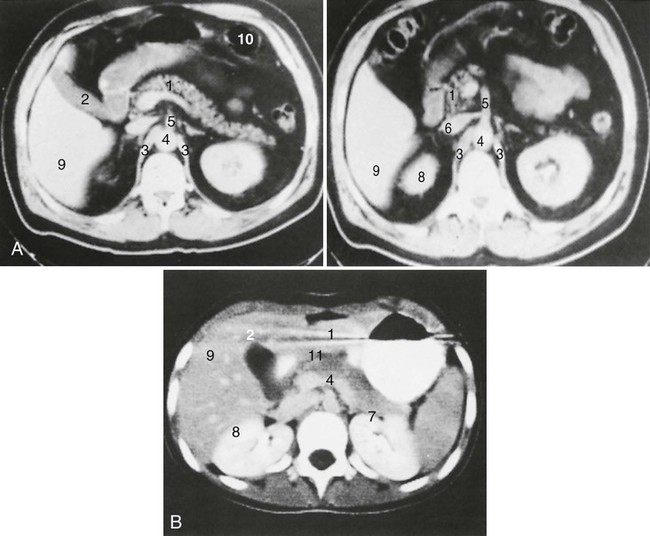

Computed tomography (CT) is a radiographic examination that provides cross-sectional images of internal anatomy (Fig. 29-8). It may be used to evaluate abdominal vasculature and identify focal points found on nuclear scans as solid, cystic, inflammatory, or vascular.14 CT detects mass lesions more than 2 cm in diameter and allows visualization and evaluation of many different aspects of GI disease. It is particularly useful in identifying pancreatic pseudocysts, abdominal abscesses, biliary obstructions, and a variety of GI neoplastic lesions.15

The procedure involves taking the patient to the CT scanner, placing the patient on the table, and inserting the area to be studied into the opening of the scanner. Multiple scans are obtained at various angles, and a computer synthesizes images of the structures being studied. Intravenous or GI contrast may be used to facilitate the imaging of the blood vessels or the GI tract, respectively.14

Nursing Management

Before the procedure, the patient should be asked about any sensitivity to contrast. The procedure usually takes 30 minutes without contrast and 60 minutes with contrast, during which time the patient must lie very still. No special interventions are required before or after the procedure.11

Hepatobiliary Scintigraphy

A hepatobiliary scan is a nuclear scan that is used to assess the status of the liver and the biliary system. It is valuable in detecting GI abnormalities such as acute and chronic cholecystitis, biliary obstruction, and bile leaks, and it yields additional information about organ size.16

The scan involves injecting an intravenous technetium 99m (99mTc)–labeled iminodiacetic agent (radiotracer), such as disofenin (DISIDA) or mebrofenin (TMBIDA). Serial images are then obtained using a gamma (scintillation) camera. The liver cells take up 80% to 90% of the radiotracer, which is then secreted into the bile and transported throughout the biliary system, allowing visualization of the biliary tract, the gallbladder, and the duodenum.7 Pooling of the iminodiacetic agent around the liver indicates poor uptake and hepatocellular dysfunction.16

Nursing Management

The hepatobiliary scan is relatively noninvasive and safe, although the patient must be transported to the nuclear medicine department. The patient may need to maintain NPO status for 2 to 4 hours before the procedure. Sedation is usually not required, but the patient must be able to lie flat and remain still for 60 minutes during the scanning procedure. No special interventions are required after the procedure.11

Gastrointestinal Bleeding Scan

A GI bleeding scan is used to evaluate the presence of an active bleed, to identify the site of the bleed, and to assess the need for an arteriogram.17 The GI bleeding scan is sensitive to low rates of bleeding (0.1 milliliters per minute [mL/min]), but it is reliable only when the patient is actively bleeding.7,17

The scan is usually performed with intravenous 99mTc-labeled sulfur colloid or 99mTc-labeled red blood cells (radiotracers). To tag the red blood cells, a blood sample is taken from the patient. The red blood cells are separated, tagged with 99mTc, and then returned to the patient. Serial images are obtained using a gamma (scintillation) camera. Extravasation and accumulation or pooling of radiotracers in the bowel lumen indicates active bleeding is occurring and facilitates identification of the site.7,17

Nursing Management

The GI bleeding scan is relatively noninvasive and safe, although the patient must be transported to the nuclear medicine department. Sedation usually is not required, but the patient must be able to lie flat and remain still for 60 minutes or longer during the scanning procedure. No special interventions are required after the procedure.11

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to identify tumors, abscesses, hemorrhages, and vascular abnormalities. Small tumors, whose tissue densities are different from those of the surrounding cells, can be identified before they would be visible on any other radiographic test.7 Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is a form of MRI that is used to assess blood vessels and blood flow.14 Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is a form of MRI used to evaluate the biliary and pancreatic ducts.18

During MRI, the patient is placed in a large magnetic field that stimulates the protons of the body. Introduction of radiofrequency waves causes resonance of these protons, which then emit an image that a computer is able to reconstruct for viewing. Intravenous administration of a non–iodine-based contrast medium enhances the image by influencing the magnetic environment and signal intensity.14

Nursing Management

The MRI procedure is lengthy and requires that the patient be transported to the scanner. The patient must lie motionless in a tight, enclosed space (if a closed MRI scanner is used), and sedation may be necessary. Removal of all metal from the patient’s body is essential because the basis of MRI is a magnetic field. Patients with implanted metal objects are not candidates for the procedure. No special interventions are required after the procedure.11

Percutaneous Liver Biopsy

Liver biopsy is a diagnostic procedure that is used to evaluate liver disease. Morphologic, biochemical, bacteriologic, and immunologic studies are performed on the tissue sample to diagnose liver disorders such as cirrhosis, hepatitis, infections, or cancer. A biopsy can also yield information about the progression of the patient’s disease and response to therapy.7,19

Percutaneous liver biopsy can be performed at the bedside or in the imaging department and involves the use of an imaging-guided needle.20 Before the test, the patient should maintain NPO status for 6 hours and have blood drawn for coagulation studies. The procedure is performed by anesthetizing the pericapsular tissue, inserting a coring or suction needle between the eighth and ninth intercostal space into the liver while the patient holds his or her breath on exhalation, withdrawing the needle with the sample, and applying pressure to stop the bleeding.7

Nursing Management

During liver biopsy, the patient may experience a deep pressure sensation or dull pain that radiates to the right shoulder. After the procedure, the patient is positioned on the right side for 2 hours and kept on complete bed rest for the next 6 to 8 hours.7,19 Hemorrhage is the major complication associated with liver biopsy, although it occurs in less than 1% of patients. Other complications include damage to neighboring organs (e.g., kidney, lung, colon, gallbladder), bile peritonitis, hemothorax, and infection at the needle site. Puncturing of the gallbladder can cause leakage of bile into the abdominal cavity, resulting in peritonitis.19

Summary

History

• A review of the patient’s current illness and symptoms, including the presence or absence of bleeding, abdominal pain, and dysphagia, is an important part of obtaining the patient’s history.

• If the patient’s condition permits, additional information regarding the patient’s personal and social status, general health status, and family history, including nutritional intake, oral hygiene, and bowel elimination, should be obtained.

Clinical Assessment

• To prevent stimulation of GI activity, the order for the assessment should be changed to inspection, auscultation, percussion, and palpation.

• Inspection should focus on the oral cavity, skin, and abdomen.

• Auscultation provides clinical data on the status of the bowel’s motility.

• Normal bowel sounds are high-pitched, gurgling sounds that occur approximately every 5 to 15 seconds, and colonic sounds are low pitched and have a rumbling quality.

• Percussion is used to elicit information about deep organs such as the liver, spleen, and pancreas.

• Light and deep palpation methods are used to detect pathologic conditions of the abdomen.

Diagnostic Procedures

• Fiberoptic endoscopy is a diagnostic procedure for the direct visualization and evaluation of the GI tract.

• Angiography is used diagnostically to evaluate the status of GI circulation and therapeutically to achieve control of GI bleeding.

• An abdominal radiograph is useful in the diagnosis of a bowel obstruction and perforation.

• Abdominal ultrasound is used to evaluate the status of the gallbladder and biliary system, the liver, the spleen, and the pancreas.

• CT provides cross-sectional images of the internal anatomy of the abdomen and is used to evaluate abdominal vasculature and identify focal points found on nuclear scans as solid, cystic, inflammatory, or vascular.

• A hepatobiliary scan is a nuclear scan that is used to assess the status of the liver and the biliary system.

• A gastrointestinal bleeding scan is used to evaluate the presence of an active GI bleed, to identify the site of the bleed, and to assess the need for an arteriogram.

• MRI is used to identify tumors, abscesses, hemorrhages, and vascular abnormalities.

• Liver biopsy is a diagnostic procedure that is used to evaluate liver disease.