CHAPTER 8 Gastrectomy

Case Study

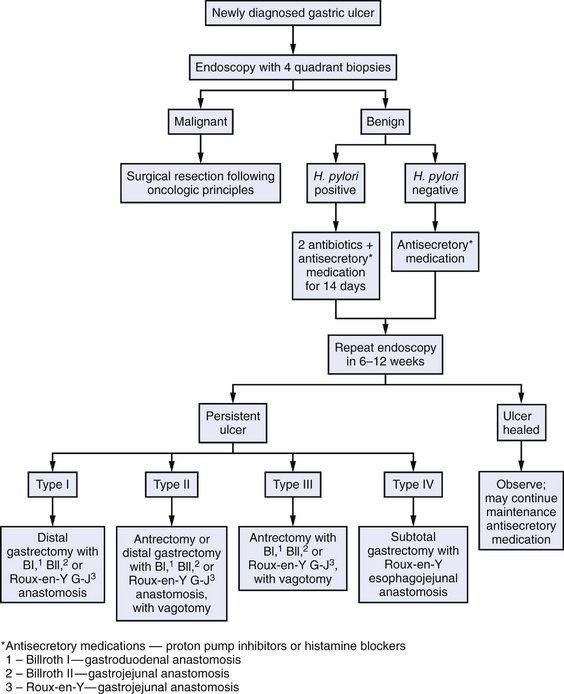

Repeat endoscopy shows a nonhealing ulcer. Biopsy of the rim of the ulcer reveals adenocarcinoma.

BACKGROUND

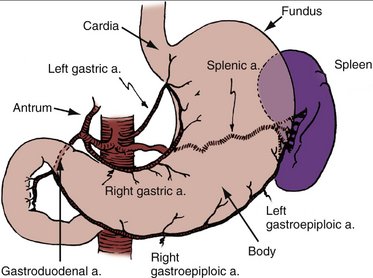

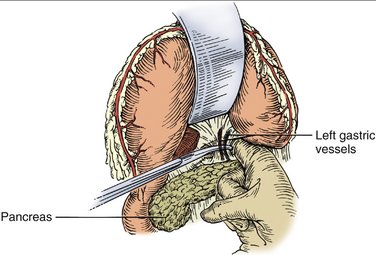

The stomach may be divided into four anatomic regions: the cardia, fundus, body, and antrum. The stomach derives its blood supply from four main arterial trunks: the right and left gastric arteries along the lesser curvature and the right and left gastroepiploic arteries along the greater curvature. Additional blood supply is provided by the short gastric arteries (Fig. 8-1). Given this extensive collateral vascular network, the stomach may remain viable after ligation of multiple main feeding vessels. Venous and lymphatic drainage, in general, follows the arterial supply.

INDICATIONS FOR GASTRECTOMY

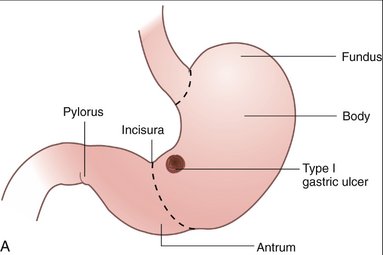

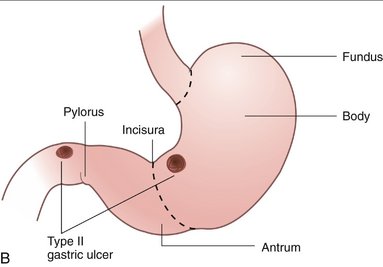

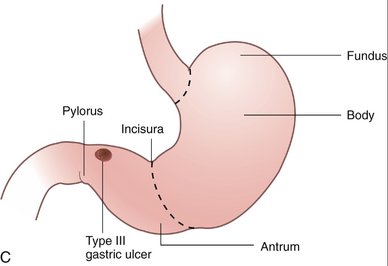

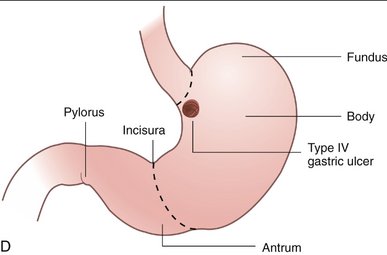

| Johnson Classification | Location | Acid Hypersecretion |

|---|---|---|

| Type I | Lesser curve | No |

| Type II | Lesser curve and duodenum | Yes |

| Type III | Prepyloric | Yes |

| Type IV | Proximal lesser curve near gastroesophageal junction | No |

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

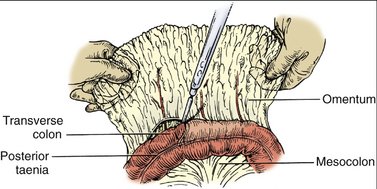

COMPONENTS OF THE OPERATION AND APPLIED ANATOMY

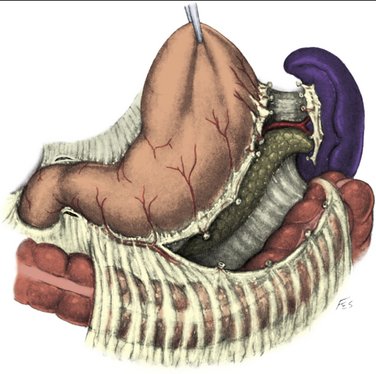

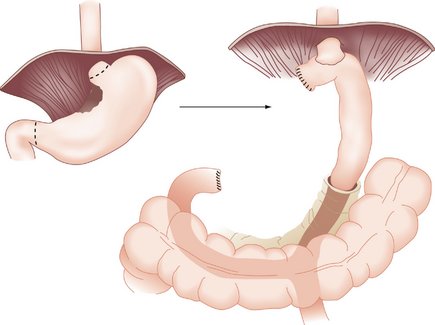

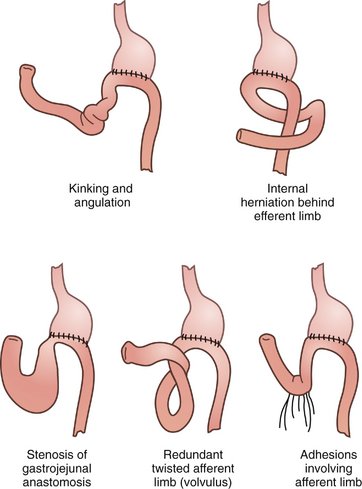

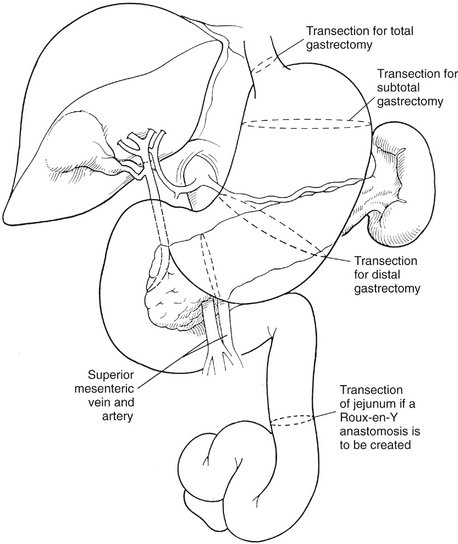

Total gastrectomy is described below. Unique features of partial resections (Fig. 8-4), including reconstructive options, are discussed in the subsequent section on additional operative considerations.

Figure 8-4 The levels of transection of the stomach for total, subtotal, or distal gastrectomy.

(From Khatri VP, Asensio JA: Operative Surgery Manual. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2003.)

Patient Positioning and Preparation

Preoperative Considerations

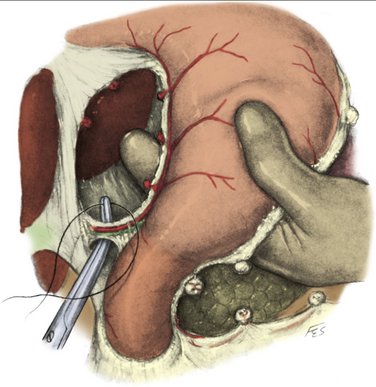

Exposure and Dissection: Total Gastrectomy

Reconstruction: Roux-en-Y Anastomosis

Additional Operative Considerations

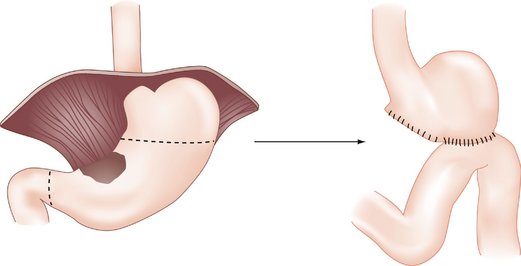

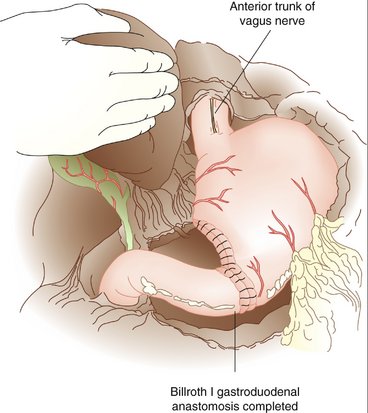

Figure 8-10 Partial gastrectomy with Billroth I reconstruction.

(From Dempsey D, Pathak A: Antrectomy. Op Tech Gen Surg 5:86–100, 2003.)