Chapter 22 Gait Disorders

Physiological and Biomechanical Aspects of Gait

History and Common Symptoms of Gait Disturbance

Sensory Symptoms and Pain Associated with Gait Disorders

Incontinence and Gait Disorders

Examination of Posture and Walking

Discrepancies on Examination of Gait

Classification of Gait Patterns

Elderly Gait Patterns, Cautious Gaits, and Fear of Falling

Perceptions of Instability and Illusions of Movement

Anatomical Aspects of Gait

The neuroanatomical structures responsible for equilibrium and locomotion in humans are inferred from studies in lower species that suggest two basic systems. First, brainstem locomotor centers (Takakusaki, 2008) project through descending reticulospinal pathways into the ventromedial spinal cord. Stimulation of brainstem locomotor centers results in an increase in axial and limb muscle tone to assume an upright posture before stepping begins. Second, assemblies of spinal interneurons (central pattern generators or spinal locomotor centers) activate motoneurons of limb and trunk muscles in a patterned and repetitive manner to drive stepping movements and stimulate propriospinal networks that link the trunk and limbs to facilitate the synergistic coordinated limb and trunk movements of locomotion. In quadrupedal animals, spinal locomotor centers are capable of maintaining and coordinating rhythmic stepping movements after spinal transection. The cerebral cortex and corticospinal tract are not necessary for experimentally induced locomotion in quadrupeds but are required for precision stepping. The isolated spinal cord in humans can produce spontaneous movements, but it cannot generate rhythmic stepping or maintain truncal balance, indicating that brainstem and higher cortical connections are necessary for bipedal walking in humans. In monkeys, spinal stepping requires preservation of the descending ventromedial brainstem and ventrolateral spinal motor pathways. Lesions of the medial brainstem in monkeys interrupt descending reticulospinal, vestibulospinal, and tectospinal systems, resulting in dysequilibrium.

History and Common Symptoms of Gait Disturbance

Slowness and Stiffness

Slowness of walking is encountered in the elderly and in most gait disorders. Recent pooled analysis from nine selected cohorts has provided evidence that the speed of gait may correlate with longer survival in older adults (Studenski et al., 2011). Walking slowly is a normal reaction to unstable or slippery surfaces that cause postural insecurity and threaten balance. Similarly, those who feel their balance is less secure because of any musculoskeletal or neurological disorders walk slower. In Parkinson disease (PD) and other basal ganglia diseases, slowness of walking is due to shuffling with short, shallow steps. Difficulty initiating stepping when starting to walk (start hesitation) and when encountering an obstacle or turning (freezing) are common in more advanced stages of parkinsonian syndromes.

Examination of Posture and Walking

A scheme for the examination of posture and walking is summarized in Box 22.1. A convenient starting point is to observe the overall pattern of limb and body movement during walking. Normal walking progresses in a smooth and effortless manner. The truncal posture is upright, and the legs swing in a fluid motion with a regular stride length. Synergistic head, trunk, and upper-limb movement flow with each step. Observation of the pattern of body and limb movement during walking also helps the examiner decide whether the gait problem is caused by a focal abnormality (e.g., shortening, hip disease, muscle weakness) or a generalized disorder of movement, and whether the problem is unilateral or bilateral. After observing the overall walking pattern, the specific aspects of posture and gait should be examined (see Box 22.1).

Box 22.1 Examination of Gait and Balance*

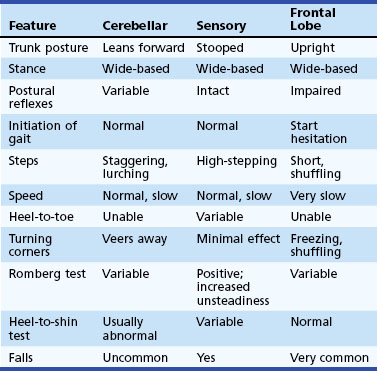

Stance

The width of the stance base (the distance between the feet) during quiet arising from sitting, standing, and walking gives some indication of balance. Wide-based gaits are typical of cerebellar or sensory ataxia but also may be seen in diffuse cerebrovascular disease and frontal lobe lesions (Table 22.1). Widening the stance base is an efficient method of reducing body sway in the lateral and anteroposterior planes. Persons whose balance is insecure for any reason tend to adopt a wider stance and a posture of mild generalized flexion and to take shorter steps. Those who have attempted to walk on ice or other slippery surfaces will recognize this phenomenon. Eversion of the feet is another manner in which to increase stability and is particularly common in patients with diffuse cerebrovascular disease. Spontaneous sway, drift of the body in any direction, postural tremor, or ability to stay upright without touching furniture or assistance of another person are important clues.

Trunk Posture

The trunk is normally upright during standing and walking. Flexion of the trunk and a stooped posture are prominent features in PD. Slight flexion at the hips to lower the trunk and shift the center of gravity forward to minimize posterior body sway and reduce the risk of falling backward is common in many unsteady cautious gait syndromes. Neck and trunk extension is characteristic of progressive supranuclear palsy. Neck flexion occurs with weakness of the neck extensors in motor neuron disease and myasthenia and as a dystonic manifestation in multiple system atrophy and parkinsonism. An exaggerated lumbar lordosis, caused by hip-girdle weakness, is typical of proximal myopathies. Paraspinal muscle spasm and rigidity also produces an exaggerated lumbar lordosis in the stiff person syndrome. Tilt of the trunk to one side in dystonia is accompanied by axial muscle spasms, the most common being an exaggerated flexion movement of the trunk and hip with each step. Truncal tilt away from the affected side is observed in some acute vascular lesions of the thalamus and basal ganglia. Misperception of truncal posture and position results in inappropriate movements to correct the perceived tilt in the pusher syndrome, associated with posterolateral thalamic hemorrhages (Karnath et al., 2005). Acute vestibular imbalance in the lateral medullary syndrome leads to sway or tilt toward the side of the lesion (lateropulsion). Abnormal truncal postures occur in paraspinal myopathies that produce weakness of trunk extension and a posture of truncal flexion (camptocormia). Dystonia and parkinsonism also may alter truncal posture and lead to camptocormia or lateral truncal flexion (Pisa syndrome). Abnormal thoracolumbar postures also result from spinal ankylosis and spondylitis. A restricted range of spinal movement and persistence of the abnormal spinal posture when supine or during sleep are useful pointers toward a bony spinal deformity as the cause of an abnormal truncal posture. Truncal postures, particularly in the lumbar region, can be compensatory for shortening of one lower limb, lumbar or leg pain, or disease of the hip, knee, or ankle.

Postural Responses

Reactive postural responses are examined by sharply pulling the upper trunk backward or forward while the patient is standing. The pull should be sufficient to require the patient to step to regain their balance. This maneuver is referred to as the pull test (Hunt and Setni, 2006). The examiner must be prepared, generally by having a wall behind them, to prevent the patient from falling. A few short, shuffling steps backward (retropulsion) or a backwards fall after backward displacements, or forward (propulsion) after forward displacements, suggest impairment of postural righting (reactive postural) reactions. Falls after postural changes such as arising from a chair or turning while walking suggest impaired anticipatory postural responses. Falls without rescue arm movements or stepping movements to break the fall indicate loss of protective postural responses. Injuries sustained during falls provide a clue to the loss of these postural responses. A tendency to fall backward spontaneously is a sign of impaired postural reflexes in progressive supranuclear palsy and gait disorders associated with diseases of the frontal lobes.

Motor and Sensory Examination

Changes in muscle tone such as spasticity, lead-pipe or cogwheel rigidity, or paratonic rigidity (gegenhalten) point toward diseases of the upper motor neuron, basal ganglia, and frontal lobes, respectively. In the patient who complains of symptoms in only one leg, a detailed examination of the other leg is important. If signs of an upper motor neuron syndrome are present in both legs, a disorder of the spinal cord or parasagittal region is likely. Muscle bulk and strength are examined for evidence of muscle wasting and the presence and distribution of muscle weakness. Examination reveals whether the abnormal posture of the leg in a patient with foot drop (Box 22.2) is caused by spasticity or weakness of ankle dorsiflexors, which in turn may be due to anterior horn cell disease, a peripheral neuropathy, a peroneal compression neuropathy, or an L5 root lesion. Joint position sense should be examined for defects of proprioception in the ataxic patient or awkward posturing of the foot. Other signs such as a supranuclear gaze palsy, ataxia, and frontal lobe release signs should be sought where relevant.

Classification of Gait Patterns

Lower-Level Gait Disorders

Middle-Level Gait Disorders

Tremor of the Trunk and Legs

Leg tremor in benign essential tremor is occasionally symptomatic, but leg tremor is generally overshadowed by tremor of the upper limbs. Trunk and leg tremor may contribute to unsteadiness in cerebellar disease (see cerebellar gait above). Orthostatic tremor has a unique frequency (16 Hz) and distribution, affecting trunk and leg muscles while standing. This rapid tremor produces an intense sensation of unsteadiness rather than shaking, which is relieved by walking or sitting down. Patients avoid standing still (e.g., in a queue) and may shuffle on the spot or pace about in an effort to avoid the unsteadiness experienced when standing still. Falls are rare. Examination reveals only a rippling of the quadriceps muscles during standing, and the rapid tremor is often only appreciated by palpation of leg muscles. Recording the patterns of electromyographic activity in leg muscles assists the differential diagnosis of involuntary movements of the legs when standing (Box 22.3).

Higher-Level Gait Disorders

Hypokinetic Higher-Level Gait Patterns

With progression of PD, freezing of gait, dysequilibrium, and falls become increasingly troublesome and do not respond to increasing doses of levodopa. There is some evidence from clinical, imaging, and pathological studies to suggest that dysequilibrium is mediated via mechanisms other than dopaminergic deficiency, and subcortical cholinergic projections from the pedunculopontine nucleus have been implicated (Bohnen et al., 2009). Falls occur late in the course of PD, and a number of causes must be considered. These include festinating steps that are too small to restore balance, tripping or stumbling over rough surfaces because shuffling steps fail to clear small obstacles, and failure to step, with start hesitation and freezing. In each of these examples, falling stems from locomotor hypokinesia and a lack of normal-sized, rapid, compensatory voluntary movements. These falls are forward onto knees and outstretched arms (indicating preservation of rescue reactions). Other falls, in any direction, occur when changing posture or turning in small spaces and result from loss of postural and righting responses, either spontaneously when multitasking or after minor perturbations. It is also important to consider collapsing falls related to orthostatic hypotension, a common finding in PD.

Unlike the hypokinetic steps and flexed truncal posture, the loss of postural and righting responses generally does not respond to levodopa. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subthalamic nucleus (STN) or the globus pallidus interna (GPi) may improve gait but also may worsen gait and may be associated with increased falls (Ferraye et al., 2008; Weaver et al., 2009). DBS in the region of the pedunculopontine nucleus is under investigation for disequilibrium and freezing of gait, with mixed results (Ferraye et al., 2010).

Similar slowness of leg movement and shuffling occurs in a variety of other akinetic-rigid syndromes (Box 22.4), the most common of which are multiple system atrophy, corticobasal degeneration, and progressive supranuclear palsy. A number of clinical signs help distinguish among these conditions (Table 22.2). In progressive supranuclear palsy, the typical neck posture is one of extension, with axial and nuchal rigidity rather than neck and trunk flexion as in PD. A stooped posture with exaggerated neck flexion is sometimes a feature of multiple system atrophy. A distinguishing feature of progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy is the early appearance of falls due to loss of postural and righting responses, in comparison to the preservation of these reactions in PD until later stages of the illness. There also may be an element of ataxia in these akinetic-rigid syndromes that is not evident in PD. Falls occur in 80% of patients with progressive supranuclear palsy and can be dramatic, leading to injury. The disturbance of postural control in progressive supranuclear palsy is coupled with impulsivity due to frontal executive dysfunction that leads to reckless lurching movements during postural changes, such as sitting or arising, and toppling falls. Accordingly, the patient who presents with falls and an akinetic-rigid syndrome is more likely to have one of these variants of parkinsonism rather than PD. Finally, the dramatic response to levodopa that is typical of PD does not occur in these variants of parkinsonism, although some cases of multiple system atrophy respond partially for a short period.

Box 22.4 Differential Diagnosis of an Akinetic-Rigid Syndrome and Gait Disturbance

Table 22.2 Summary of Clinical Features Differentiating Parkinson Disease from Symptomatic Parkinsonism in Patients with an Akinetic-Rigid Gait Syndrome

| Feature | Parkinson Disease | Symptomatic Parkinsonism |

|---|---|---|

| Posture | Stooped (trunk flexion) | Stooped or upright (trunk flexion/extension) |

| Stance | Narrow | Often wide-based |

| Initiation of walking | Start hesitation | Start hesitation, magnetic feet |

| Steps | Small, shuffling | Small, shuffling |

| Stride length | Short | Short |

| Freezing | Common | Common |

| Leg movement | Stiff, rigid | Stiff, rigid |

| Speed | Slow | Slow |

| Festination | Common | Rare |

| Arm swing | Minimal or absent | Reduced or excessive |

| Heel-to-toe walking | Normal | Poor (truncal ataxia) |

| Postural reflexes | Preserved in early stages | Absent at early stage |

| Falls | Late (forward, tripping) | Early and severe (backward, tripping, or without apparent reason) |

In addition to the advanced hypokinetic disorders discussed previously, frontal lobe tumors (glioma or meningioma), anterior cerebral artery infarction, obstructive or communicating hydrocephalus (especially normal-pressure hydrocephalus), and diffuse cerebrovascular disease (multiple lacunar infarcts and Binswanger disease) also produce disturbance of gait and balance. These pathologies interrupt connections between the frontal lobes and other cortical and subcortical structures. The clinical appearance of the gait of patients with such lesions varies from a predominantly wide-based ataxic gait to an akinetic-rigid gait with slow, short steps and a tendency to shuffle. It is common for a patient to present with a combination of these features. In the early stages, the stance base is wide, with an upright posture of the trunk and shuffling when starting to walk or turning corners. There may be episodes of freezing. Arm swing is normal or even exaggerated, giving the appearance of a “military two-step” gait. The normal fluidity of trunk and limb motion is lost. Examination reveals normal voluntary upper-limb and hand movements and a lively facial expression. This “lower-half parkinsonism” is commonly seen in diffuse cerebrovascular disease. The marche à petits pas of Dejerine and Critchley’s atherosclerotic parkinsonism refer to a similar clinical picture. Patients with this clinical syndrome commonly are misdiagnosed as having PD. The normal motor function of the upper limbs, retained arm swing during walking, upright truncal posture, wide-based stance, upper motor neuron signs including pseudobulbar palsy, and the absence of a resting tremor distinguish this syndrome from PD. In addition, the lower-half parkinsonism of diffuse cerebrovascular disease does not respond to levodopa treatment (see Box 22.4). Walking speed in subcortical arteriosclerotic encephalopathy is slower than in cerebellar gait ataxia or PD (Ebersbach et al., 1999). Slowness of movement and the lack of heel-to-shin ataxia distinguish the wide-based stance of this syndrome from that of cerebellar gait ataxia (see Table 22.1).

Elderly Gait Patterns, Cautious Gaits, and Fear of Falling

Elderly patients with an insecure gait characterized by slow short steps, en bloc turns, and falls often have signs of multiple neurological deficits such as peripheral motor (mild proximal) weakness, subtle sensory loss (mild distal light touch and proprioceptive loss, blunted vestibular or visual function), and even mild spastic paraparesis due to cervical myelopathy, without any one lesion being severe enough to explain the walking difficulty. The cumulative effect of these multiple deficits may interfere with perceived stability and equilibrium. Along with musculoskeletal disorders, postural hypotension, and loss of confidence (especially after falls), these factors contribute to a cautious gait pattern. In this situation, brain imaging is valuable to look for subcortical white-matter ischemia (especially in the frontal lobes and periventricular regions) that correlates with imbalance, increased body sway, falls, and cognitive decline (Baezner et al., 2008).

Perceptions of Instability and Illusions of Movement

A number of syndromes have been described in which middle-aged individuals complain of unsteadiness and imbalance associated with “dizziness,” sensations or illusions of semicontinuous body motion, sudden brief body displacements, or body tilt. In some, the symptoms develop in open spaces where there are no visible supports (space phobia). Others develop sensations in particular situations such as on bridges, stairs, and escalators or in crowded rooms, leading to the development of phobic avoidance behavior and the syndrome of phobic postural vertigo (Brandt, 1996). Prolonged illusory swaying and unsteadiness after sea or air travel is referred to as the mal de débarquement syndrome. Past episodes of a vestibulopathy may suggest the possibility of a subtle semicircular canal or otolith disturbance, but a disorder of vestibular function is rarely confirmed in these syndromes. A fear of falling, anxiety, and related complaints are common accompaniments. These symptoms must be distinguished from the physiological “vertigo” and unsteadiness accompanying visual vestibular mismatch or conflict when observing moving objects, focusing on distant objects in large panoramas, or looking upward at moving objects.

Hysterical and Psychogenic Gait Disorders

A gait disorder is one of the more common manifestations of a psychogenic or hysterical movement disorder. The typical gait patterns encountered include transient fluctuations in posture while walking; knee buckling without falls; excessive slowness and hesitancy; a crouched, stooped, or other abnormal posture of the trunk; complex postural adjustments with each step; exaggerated body sway or excessive body motion especially brought out by tandem walking; and trembling, weak legs (Hayes et al., 1999). The more acrobatic hysterical disorders of gait indicate the extent to which the nervous system is functioning normally and is capable of high-level coordinated motor skills to perform various complex maneuvers. Suggestibility, variability, improvement with distraction, and a history of sudden onset or a rapid, dramatic, and complete recovery are other features of psychogenic gait (and movement) disorders. One must be cautious in accepting a diagnosis of hysteria, however, because a bizarre gait may be a presenting feature of primary torsion dystonia, and unusual truncal and leg postures may be encountered in truncal and leg tremors. Finally, higher-level gait disorders often have a disconnect between the standard neurological exam and the gait pattern.

Musculoskeletal Disorders and Antalgic Gait

Baezner H., Blahak C., Poggesi A., et al. Association of gait and balance disorders with age-related white matter changes: the LADIS study. Neurology. 2008;70:935-942.

Bohnen N.I., Muller M.L., Koeppe R.A., et al. History of falls in Parkinson’s disease is associated with reduced cholinergic activity. Neurology. 2009;73:1670-1676.

Brandt T. Phobic postural vertigo. Neurology. 1996;46:1515-1519.

Ebersbach G., Sojer M., Valldeoriola F., et al. Comparative analysis of gait in Parkinson’s disease, cerebellar ataxia and subcortical arteriosclerotic encephalopathy. Brain. 1999;122:1349-1355.

Ferraye M.U., Debu B., Fraix V., et al. Effects of subthalamic nucleus stimulation and levodopa on freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2008;70:1431-1437.

Ferraye M.U., Debu B., Fraix V., et al. Effects of pedunculopontine nucleus area stimulation on gait disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2010;133:205-214.

Hayes M.W., Graham S., Heldorf P., et al. A video review of the diagnosis of psychogenic gait: appendix and commentary. Mov Disord. 1999;14:914-921.

Hunt A.L., Sethi K.D. The pull test: a history. Mov Disord. 2006;21:894-899.

Karnath H.O., Johannsen L., Broets D., et al. Posterior thalamic haemorrhage induces “pusher syndrome. Neurology. 2005;64:1014-1019.

Studenski S., Perera S., Patel K., et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA. 2011;305:50-58.

Takakusaki K. Forebrain control of locomotor behaviours. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57:192-198.

Weaver F.M., Follet K., Stern M., et al. Bilateral deep brain stimulation vs best medical therapy for patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:63-73.