32 Gait Disorders

Etiology and Classification

Gait disorders can be classified in a number of ways: etiologically (Table 32-1), anatomically (Table 32-2), and clinically (Table 32-3; Fig. 32-1). Perhaps the most useful approach to understanding gait disorders is a clinicoanatomic one. According to this method, gait disorders can be divided into roughly three anatomic categories: cortical, subcortical, and peripheral. A variety of well-defined clinical gait syndromes can be described under each anatomic rubric.

| Myelopathy |

Table 32-2 Gait Disorders—Anatomic Classification

Table 32-3 Clinical Gait Syndromes: Specific Examples

| Gait Type | Clinical Features | Associated Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Frontal gait | ||

| Cautious gait | ||

| Psychogenic gait |

Cortical Gait Disorders

Frontal Gait

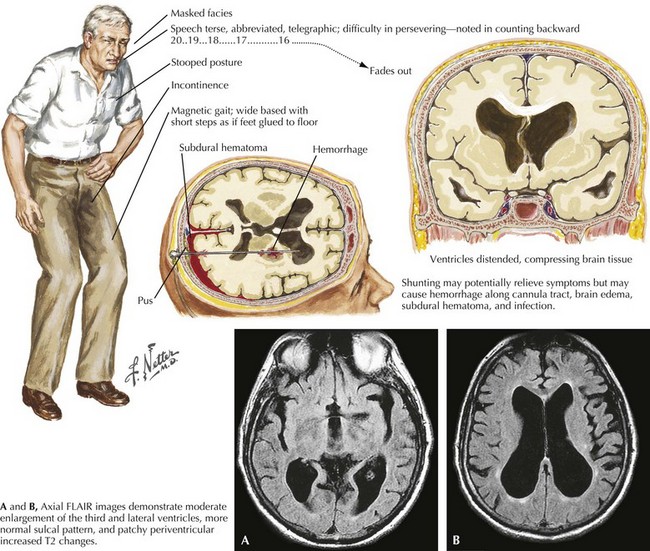

Bilateral frontal lobe dysfunction and/or disconnection between cortical and subcortical motor areas (i.e., basal ganglia, brainstem, cerebellum) leads to a distinctive gait, variously known as magnetic gait, “marche a petits pas,” lower-body parkinsonism, and frontal apraxia of gait. It is characterized by a combination of gait initiation failure, impaired walking and disequilibrium. The patient exhibits a wider than normal gait base, reduced stride length and heel strike, and shuffling steps (Fig. 32-2). There is often a pronounced hesitation to the initiation of the gait. Such patients frequently exhibit retropulsion, something that often leads to falls backwards. Paradoxically, there is usually preservation of other types of leg movements, that is, pedaling or bicycling in the recumbent position (hence the term apraxia of gait).

Frontal gait, on initial clinical assessment, can resemble parkinsonian gait, although there is generally only involvement of the lower body (hence the term lower-body parkinsonism). Features that can help differentiate frontal gait from typical parkinsonian gait are more erect posture, wide base, lack of tremor, and preserved arm swing. Patients can sometimes develop freezing of gait (see hypokinetic-rigid gait) as well. Associated signs of frontal gait disorder include frontal release signs, behavioral changes, and executive dysfunction.

The most common cause of frontal gait is cerebrovascular disease (small vessel ischemic changes or infarcts) affecting the basal ganglia and/or periventricular white matter. Normal-pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is another and very important etiology, particularly because it is potentially remediable. NPH is characterized by the clinical triad of frontal gait disorder, urinary incontinence, and dementia. Imaging of the brain demonstrates hydrocephalus (Fig. 32-2). Diagnostic workup includes large-volume lumbar puncture, which reveals improvement of gait hours to days after removal of CSF. Treatment involves placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

Subcortical Gait Disorders

Spastic Gait

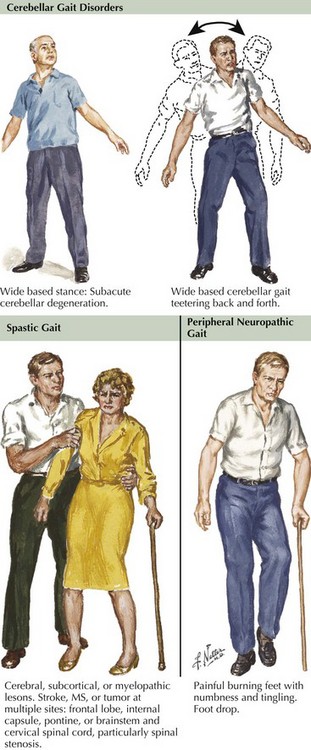

This represents a pyramidal gait disorder, originating in the motor cortex or corticospinal tracts. Unilateral disease leads to a spastic hemiparetic gait characterized by stiff-legged extension and circumduction of the affected leg (Fig. 32-1, middle row) and flexion of the ipsilateral upper limb. In the case of bilateral involvement, the patient exhibits adduction and scissoring of the legs. Associated findings include leg weakness, hyperreflexia, and extensor plantar responses. Causes of hemiparetic gait include stroke, demyelinating lesion, mass, or trauma. Paraparetic gait can be caused by cerebral palsy, primary lateral sclerosis, and spinal cord lesions. Botulinum toxin and oral medications such as baclofen and tizanidine can be beneficial.

Ataxic Gait

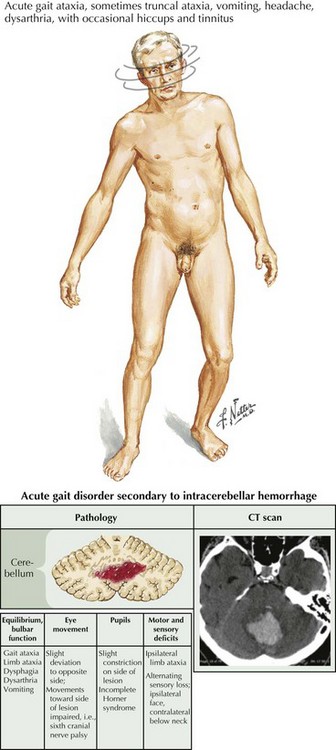

The gait has a lurching or veering quality, imitating a “drunken gait” that is marked by a widened base of support and irregular stepping. These patients also exhibit increased truncal instability that is exacerbated with standing with one’s feet together or tandem walking. Ataxic gait disorders signal cerebellar dysfunction (Fig. 32-1 top row). On examination, other signs of cerebellar disease can be elicited: dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesia, nystagmus, hypermetric saccades, and scanning dysarthria.

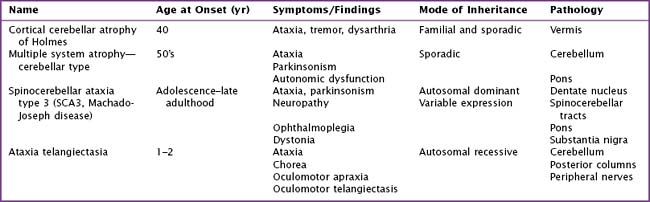

Causes are myriad: (Table 32-4, Table 32-5) toxic/metabolic disorders (i.e. acute or chronic alcoholism), neurodegenerative diseases such as the spinocerebellar ataxias, paraneoplastic disease, and ischemic (Fig. 32-3) or demyelinating disorders affecting the cerebellum or its connections. Pharmacologic treatments to date have been unsuccessful. Physical therapy is the main treatment available.

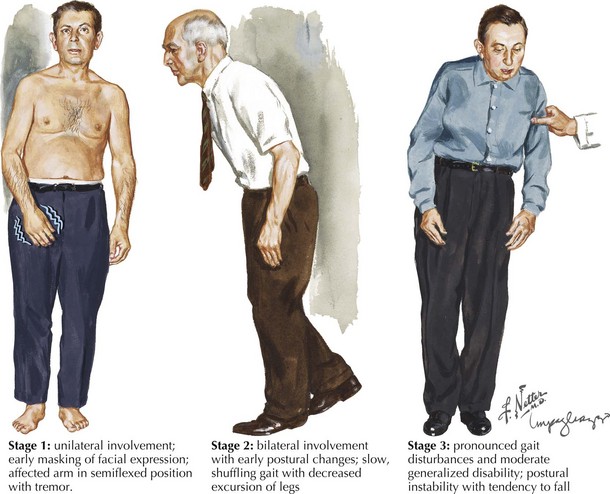

Hypokinetic-Rigid Gait

Common etiologies of hypokinetic-rigid gait include neurodegenerative disorders such as idiopathic PD and atypical parkinsonian syndromes, that is, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and corticobasal ganglionic degeneration (Fig. 32-4). One distinguishing feature between PD and other causes of parkinsonism is that the former is characterized by a normal or narrow base and the latter exhibits a broad-based gait. In addition, PD tends to start unilaterally versus the bilaterality seen with the atypical syndromes. Furthermore, the presence of a tremor is usually typical of idiopathic AD.

Peripheral Gait Disorders

Sensory Gait

These patients have a loss of proprioceptive input from the legs; they tend to walk with a wide base and reduced stride length. Arms are usually held in abduction. Gait unsteadiness is markedly worsened when visual input is reduced, that is, in the dark or closing the eyes. Lesions of the large-fiber sensory afferent nerves including peripheral neuropathies, dorsal root lesions, sensory ganglionopathies, and posterior column damage account for the typical sensory gait disorders (Fig. 32-1, bottom row).

Steppage Gait

This gait disorder results from distal anterolateral leg muscle group weakness. Weakness of foot dorsiflexors causes foot drop, and patients compensate by adopting a high-stepping gait with excessive flexion of the hips and knees. When the foot touches down, the toe or anterolateral portion of the foot touches first. These patients cannot walk on their heels because of the weakness in the dorsiflexors of the feet and toes. Associated signs include distal muscle atrophy, reduced or absent ankle reflexes, and often sensory loss. The most common cause of steppage gait is peripheral neuropathy (Fig. 32-1, bottom row).

Jankovic J, Nutt JG, Sudarsky L. Classification, diagnosis, and etiology of gait disorders. Adv Neurol. 2001;87:119-133.

Nutt JG. Classification of gait and balance disorders. Adv Neurol. 2001;87:135-141.

Nutt JG, Marsden CD, Thompson PD. Human walking and higher level gait disorders, particularly in the elderly. Neurology. 1993;43:268-279.

Ruzicka E, Jankovic JJ. Disorders of gait. In: Jankovic JJ, Tolosa E, editors. Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2002:409-429.

Snijders AH, van de Waarenburg BP, Giladi N, et al. Neurological gait disorders in elderly people: clinical approach and classification. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:63-74.

Sudarsky L. Gait disorders: prevalence, morbidity, and etiology. Adv Neurol. 2001;87:111-117.