64

Fungal Diseases

Key Points

• Cutaneous fungal diseases can be broadly divided into two groups:

– Superficial – limited to the stratum corneum, hair, and/or nails.

– Deep – dermal and/or subcutaneous.

• Superficial fungal infections can be further subdivided into:

– Noninflammatory – most commonly tinea versicolor, but includes tinea nigra and piedra.

Superficial Fungal Infections

Tinea (Pityriasis) Versicolor

• Secondary to transformation of Malassezia spp., especially M. furfur, from the yeast form to the hyphal form (see Fig. 2.1A).

• Malassezia spp. are part of the normal flora.

• Most commonly develops on the upper trunk and shoulders, but can also involve flexural sites such as the antecubital fossae, submammary folds, and groin (Fig. 64.1); in children more frequently than adults, there can also be facial involvement.

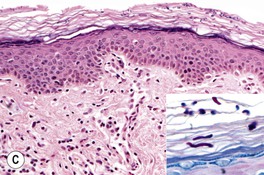

Fig. 64.1 Tinea (pityriasis) versicolor. A Hyperpigmented variant. B Hypopigmented variant on the face. C Yeast and short hyphae in the stratum corneum highlighted by a PAS stain (insert). A, B, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD; C, Courtesy, Lorenzo Cerroni, MD.

• Often first noticed in the summer, and a suntan accentuates the hypopigmented variant.

• DDx: postinflammatory hypopigmentation and idiopathic macular hypomelanosis (if hypopigmented); confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud (if hyperpigmented; see Chapter 89).

Tinea Nigra, Black Piedra, and White Piedra

• Typically seen in tropical areas.

– Most commonly due to infection with Hortaea werneckii, a pigmented fungus found in soil.

– Brown, sharply marginated macule or patch; most commonly on the palms (Fig. 64.2).

Fig. 64.2 Tinea nigra. Single, sharply demarcated brown macule on the finger. Courtesy, Frank Samarin, MD.

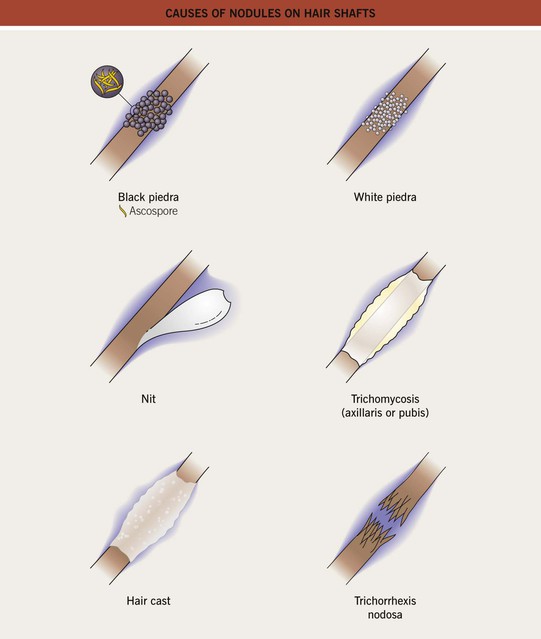

• Black piedra and white piedra are characterized by the formation of nodules on hair shafts (Table 64.2; Fig. 64.3).

Table 64.2

Comparison of black and white piedra.

| White Piedra | Black Piedra | |

| Nodule color | White (occasionally red, green, or light brown) | Brown to black |

| Nodule firmness | Soft | Hard |

| Nodule adherence to the hair shaft | Loose | Firm |

| Typical anatomic location | Face, axillae, and pubic region (occasionally scalp) | Scalp and face (occasionally pubic region) |

| Favored climate | Tropical | Tropical |

| Causative organism | Trichosporon beigelii | Piedraia hortae |

| KOH examination of ‘crush prep’ of cut hair shafts | Nondematiaceous hyphae with blastoconidia and arthroconidia (see Fig. 2.17A) | Dematiaceous hyphae with asci and ascospores (sexual reproduction) |

| Culture on Sabouraud’s agar | Moist, cream-colored, yeast-like colonies* | Slow-growing, dark green to dark brown-black colonies |

| Treatment | Clip affected hairs, wash affected hairs with antifungal shampoo | Clip affected hairs, wash affected hairs with antifungal shampoo |

* Growth inhibited by cycloheximide.

Fig. 64.3 Causes of nodules on hair shafts.

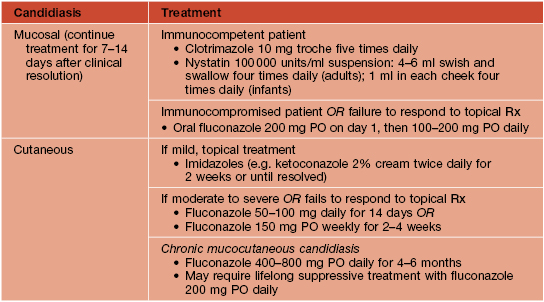

Dermatophytoses (Tinea Infections)

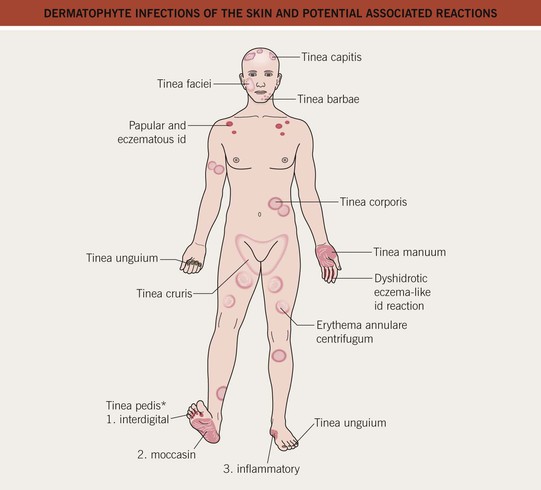

• The names of dermatophyte infections consist of the word ‘tinea’ followed by the Latin name for the involved body site; examples are tinea pedis (foot) and tinea cruris (groin) (Fig. 64.4).

Fig. 64.4 Dermatophyte infections of the skin and potential associated reactions. *Often associated with an id reaction, particularly dyshidrotic eczema-like findings on the palms and lateral digits; papular and eczematous id may also be seen, especially in association with tinea capitis. Erythema annulare centrifugum is a reaction pattern that can be idiopathic or associated with tinea infections (see Chapter 15).

• Due to fungi of three genera – Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton – that invade only keratinized tissue (stratum corneum, hair, and nails).

– Trichophyton mentagrophytes has two major variants that infect the skin, which can lead to confusion; T. mentagrophytes var. interdigitale is spread human-to-human, whereas T. mentagrophytes var. mentagrophytes is acquired from animals; these variants are also known as T. interdigitale [anthropophilic] and [zoophilic], respectively.

• The classic presentation is an erythematous, annular lesion with an active, scaly border; superficial pustules may also be present (Fig. 64.5).

Fig. 64.5 Tinea corporis. A Lesions with subtle annular configuration and border composed of individual, slightly scaly papules. B Scaly concentric rings on the arm. C Extensive figurate lesions on the neck and upper chest. D Pustules within multiple figurate lesions on the upper arm. E Tinea ‘incognito’ due to use of topical corticosteroids. A, B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD. C, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD; E, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Occasionally, vesicles may develop, especially in tinea pedis or manuum due to T. mentagrophytes.

• Dx: KOH ± fungal culture of skin scrapings (see Fig. 2.1) as well as hairs and nails, in the case of tinea capitis and tinea unguium, respectively.

– Tinea incognito refers to atypical clinical presentations, often due to inappropriate treatment with potent topical CS or combination topical therapies that contain CS; lesions may lack scale or be minimally inflamed (Fig. 64.6; see Fig. 64.5E).

Fig. 64.6 Tinea faciei. A Area of erythema and scale on the nose and philtrum of a young child. B Serpiginous lesion with minimal scale on the upper cheek of an older woman. A, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

– Majocchi’s granuloma is characterized by erythematous papules or pustules within an area of tinea corporis; the papules represent sites of hair shaft invasion, usually due to T. rubrum; often seen in women with tinea pedis who shave their legs or in immunosuppressed patients (see Fig. 31.4A; Fig. 64.7).

Examples of Specific Types of Dermatophytoses

– Most commonly due to T. rubrum or T. mentagrophytes var. interdigitale > Epidermophyton floccosum.

– Three major types: (1) interdigital – erythema, scaling, and maceration in the web spaces, especially the two lateral web spaces, which have the most occlusion; can be accompanied by fissures as well as superimposed bacterial infection; (2) moccasin – diffuse scaling and erythema that extends onto the lateral aspect of the feet; and (3) inflammatory (vesicular) – vesicles and bullae, especially on the medial aspect of the plantar surface.

– Occasionally, especially in immunocompromised and diabetic patients, a more severe ulcerative toe-web infection can occur where there is both a dermatophyte and a bacterial (e.g. pseudomonal) infection; see discussion of gram-negative toe-web infection in Chapter 61.

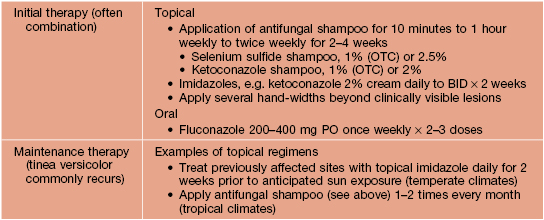

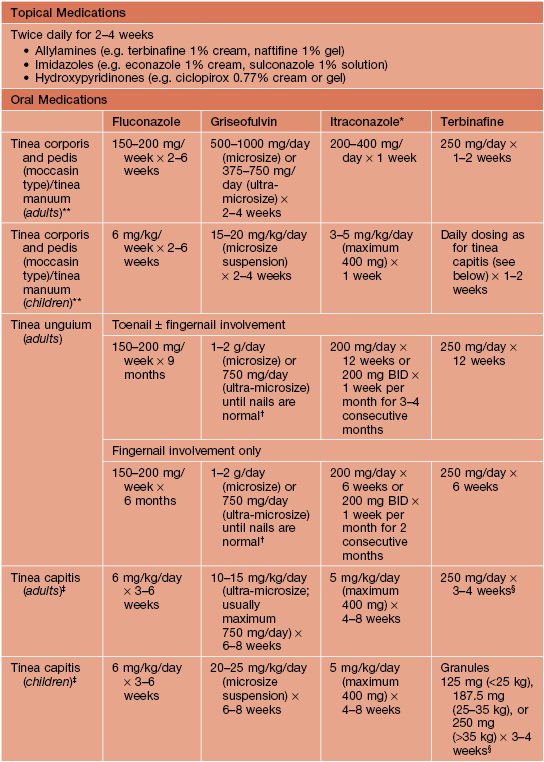

– Consider use of oral antifungal medications if the tinea pedis fails to respond to topical agents or is severe (Table 64.3).

Fig. 64.8 Tinea pedis. Diffuse scaling in the moccasin type (A), maceration between the third and fourth toes in the interdigital form (B), and erythema, scale-crust, and bullae in the inflammatory form (C). The patient in (A) also has involvement of the right hand (i.e. one hand–two feet tinea). B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Table 64.3

Therapeutic regimens for dermatophytoses.

* Not approved in the United States for use in children.

** In general, the shorter courses and lower doses tend to be used for tinea corporis.

† No longer commonly used for this indication.

‡ Combined with 2.5% selenium sulfide shampoo or ketoconazole 2% shampoo; ‘id’ reaction should not be confused with a medication allergy.

§ Not recommended for Microsporum canis, unless given at double-dose.

– Of note, onychomycosis is a more general term that includes nail infections due to dermatophytes, Candida spp., and saprophytes (up to 10% of toenail infections; Table 64.4).

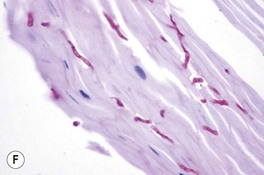

Fig. 64.9 Tinea unguium. Onycholysis, yellowing, crumbling, and thickening of the fingernails (A), thumb nails (B), and toenails (C) in the distal/lateral subungual variant. Diffuse (D) and striate (E) white discoloration of the toenail in the superficial white variant. Hyphae within a formalin-fixed, PAS-stained nail plate (F). A, C, D, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD; B, Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD; E, Courtesy, Boni Elewski, MD; F, Courtesy, Mary Stone, MD.

– Most commonly due to T. rubrum > Epidermophyton floccosum > T. mentagrophytes var. interdigitale.

• Often due to same dermatophyte as associated tinea pedis.

• Can be unilateral (‘one hand, two feet syndrome’; see Fig. 64.8A).

• Tinea unguium of the involved hand is a clinical clue.

• Tinea faciei (see Fig. 64.6).

– An arciform shape with pustules in the border points to the diagnosis.

• Tinea barbae (Fig. 64.12; see Fig. 31.7).

Fig. 64.12 Tinea barbae. More superficial form due to Trichophyton rubrum. Several follicular pustules are seen. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

– Occurs more frequently in children.

– Tinea capitis due to T. tonsurans can be more difficult to diagnose because the clinical findings may be subtle with only seborrheic dermatitis-like scaling of the scalp, minimal alopecia, and no fluorescence by Wood’s lamp examination (in contrast to ectothrix infection due to M. canis).

– Multiple spores (conidia) within or surrounding hair shafts, referred to as endothrix or ectothrix tinea capitis, respectively, cause fragility and breakage of hair, leading to areas of alopecia (see Figs. 2.2 and 2.3).

– In addition to alopecia, clinical clues include pustules, scale, and crusting; occasionally, there is formation of a kerion (see Fig. 64.13E) or development of posterior cervical and posterior auricular lymphadenopathy.

– A type of tinea capitis seen in the Mediterranean basin and Middle East is favus, in which there are keratotic masses that contain hyphae and keratin (Fig. 64.14).

– Rx: oral treatment is required; for children, an adequate dose of griseofulvin is 20–25 mg/kg/day (microsized suspension) × 6–8 weeks; combination therapy with 2.5% selenium sulfide or 2% ketoconazole shampoo is recommended to kill spores and reduce transmission; see Table 64.3 for additional oral therapies.

Fig. 64.13 Tinea capitis. The range of clinical presentations of tinea capitis due to Trichophyton tonsurans, from mild scalp scaling (A) to patchy alopecia with black dots (B) or scale (C) to large areas of alopecia with pustules and scale-crust (D). E Kerion formation due to T. tonsurans. There is a boggy plaque that can be misdiagnosed as a bacterial abscess. B, Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD.

Fig. 64.14 Favus due to Trichophyton schoenleinii. Scarring alopecia with erosions and several scutula on the occipital scalp. The latter represent masses of keratin plus fungi. Courtesy, Israel Dvoretzky, MD.

• Id reactions (see Chapter 11) can occur in the setting of dermatophyte infections; two of the more common examples are as follows (see Fig. 64.4):

– Pruritic papules favoring the upper trunk in the setting of tinea capitis, often following the initiation of appropriate therapy.

• Erythema annulare centrifugum may also be present in association with tinea pedis (see Chapter 15 and Fig. 64.4).

Superficial Mucocutaneous Candida Infections

• Most commonly due to Candida albicans or C. tropicalis.

• Wide spectrum of clinical presentations, from diaper dermatitis in infants (see Fig. 13.4) to intertrigo (see Table 60.5 and Fig. 13.2) to chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (see Chapter 49).

– Additional forms: intraoral erythematous patches and adherent white plaques, glossitis, angular cheilitis (see Fig. 13.5), and vulvovaginitis and balanitis (see Chapter 60).

– Most common presentation is an erosive, erythematous patch with satellite pustules in an intertriginous zone (inframammary, axillary, inguinal, beneath a pannus; Fig. 64.15), on the scrotum, or in the diaper area of infants (see Fig. 13.4).

Fig. 64.15 Mucocutaneous candidiasis. A Thrush with ‘cottage cheese’-like exudate on the buccal mucosa. B Candidal cheilitis with white plaques of the vermilion lip. C Angular cheilitis (perlèche). D Candidiasis of the suprapubic area, scrotum and penis in a young boy. Note the collarettes of scale on the coalescing, brightly erythematous papules. E Candidiasis of the scrotum and medial thighs with beefy red erythema, scale, and satellite papules. F This infection occurred in a hospitalized patient with diabetes mellitus who was receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics. Note the multiple satellite lesions. G Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica in the classic location between the third and fourth fingers. A, Courtesy, Judit Stenn, MD; B, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD; C, D, Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD; E, G, Courtesy, Eugene Mirrer, MD.

– Predisposing factors for cutaneous infection – similar to oral candidiasis plus hyperhidrosis with occlusion.

• DDx of candidal intertrigo: see Chapter 13.

• Rx of candidal intertrigo or balanitis: outlined in Table 60.5.

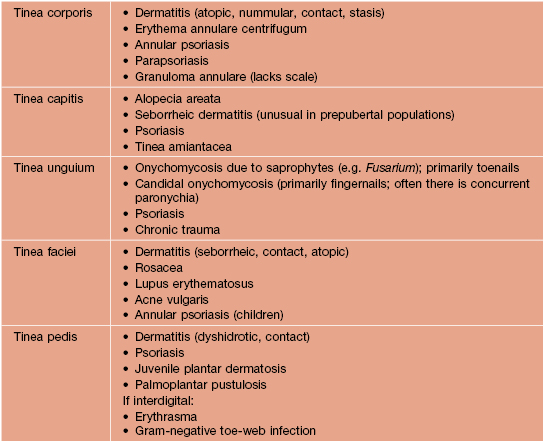

Systemic Candidiasis

• Generally affects immunosuppressed hosts in the setting of neutropenia.

• Clinical features are outlined in Table 64.6.

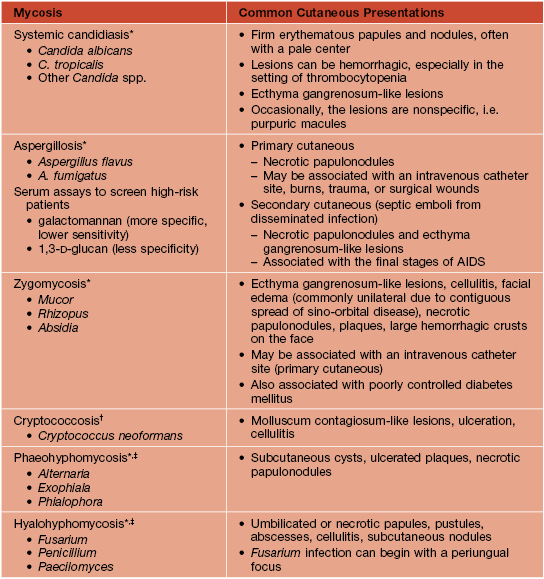

Table 64.6

Cutaneous features of common opportunistic mycoses.

* With use of prophylactic fluconazole and (more recently) voriconazole in high-risk oncology patients, incidences of systemic candidiasis and (with voriconazole use) aspergillosis have decreased, but incidences of zygomycosis and (with fluconazole use) fusariosis have increased as well as other hyalohyphomycoses.

† Especially in the setting of AIDS; also histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, penicilliosis, and sporotrichosis.

‡ Less common infections.

Congenital Candidiasis

Congenital candidiasis is discussed in Chapter 28.

Perianal Pseudoverrucous Papules (Granuloma Gluteale Infantum)

Deep Fungal Infections

Deep mycoses are treated with oral or intravenous antifungal medications, often for an extended period of time (e.g. 6 months). Culture results direct therapy, but initial empiric treatment is often started based on the clinical presentation plus histologic findings (e.g. itraconazole 200–400 mg/day for chromoblastomycosis).

Dermal/Subcutaneous

Chromoblastomycosis

• Follows trauma and implantation of the fungus into the skin.

• Expanding, verrucous plaque, usually on an extremity (Fig. 64.16); central scarring can occur.

Fig. 64.16 Chromoblastomycosis. Annular and figurate plaques due to central clearing and scarring with a verrucous surface on the arm (A) and a more granulomatous appearance on the leg (B).

Mycetoma (Madura Foot)

• Two subtypes: (1) actinomycotic mycetoma – secondary to filamentous bacteria, especially Nocardia and Actinomyces (see Chapter 61); and (2) eumycotic mycetoma – caused by true fungi, e.g. Madurella mycetomatis, Pseudallescheria boydii.

• Contracted from trauma and implantation of fungus into the skin (Fig. 64.17A).

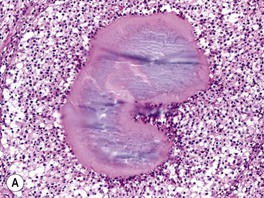

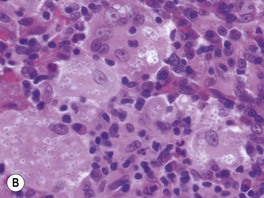

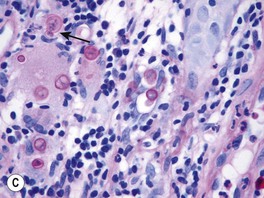

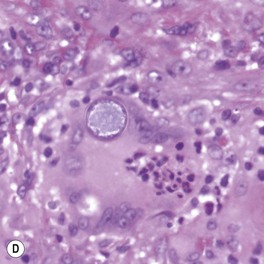

Fig. 64.17 Histologic features of selected deep fungal infections. A Eumycetoma with formation of a grain, which represents tightly packed colonies of fungal organisms. B Histoplasmosis – Histoplasma capsulatum yeast forms are present within macrophages. C Blastomycosis – budding yeast forms within the dermis, several of which are within a giant cell (PAS stain). Note the single, broad-based budding (arrow). D Coccidioidomycosis – an endospore-containing spherule within a giant cell. A, Courtesy, Lorenzo Cerroni, MD; B, D, Courtesy Jennifer McNiff, MD; C, Courtesy, Mary Stone, MD.

• Clinical triad of draining sinuses, grains (macroscopic colonies of organisms; see Chapter 61), and edema (Fig. 64.18).

Fig. 64.18 Madura foot. Note the soft tissue swelling of the foot as well as multiple nodules with pustular discharge.

• Rx: excision of more localized lesions; for larger areas of involvement as well as pre- and postoperatively, long-term course (i.e. 6 months or longer) of oral antifungal medication (e.g. itraconazole 400 mg PO daily × 3 months followed by 200 mg PO daily for 9 months).

Sporotrichosis

• Worldwide distribution; present in soil and sphagnum moss.

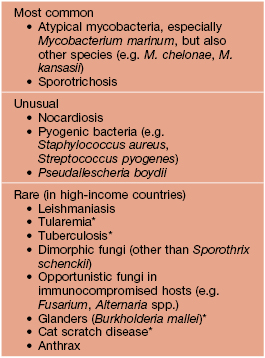

• Most common presentation is a lymphocutaneous or ‘sporotrichoid’ pattern (~75% of patients) that initially presents as a papule or nodule at the site of inoculation; this is followed by the appearance of papulonodules along the draining lymphatics (Fig. 64.19; Table 64.7).

Fig. 64.19 Lymphocutaneous (sporotrichoid) pattern. A An eroded nodule on the thumb, representing the primary lesion, with a secondary lesion along the lymphatics due to sporotrichosis. B Ulcerated nodule on the extensor forearm with multiple more proximal nodules due to nocardiosis in a patient with lymphoma who was receiving systemic corticosteroids. B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Table 64.7

Infectious causes of a lymphocutaneous (‘sporotrichoid’) pattern.

There are also noninfectious causes, such as lymphoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and in-transit metastases. In addition, perineural spread of leprosy can mimic a lymphocutaneous pattern.

* Often ulceroglandular.

• Less common variants: (1) a fixed, ulcerated plaque on the face in someone with prior exposure, a form prevalent in Brazil due to transmission by infected cats; and (2) cutaneous dissemination from a systemic infection.

Systemic (Unless Primary Inoculation into Skin)

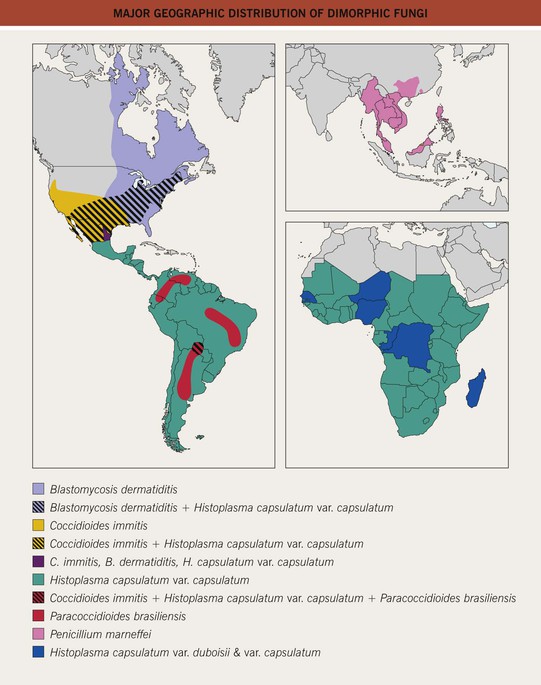

Blastomycosis

• Due to Blastomyces dermatitidis, a dimorphic fungus; yeast form displays broad-based budding (see Fig. 64.17C).

• Endemic to the southeastern United States and other areas of North America (Fig. 64.20).

• Cutaneous lesions can vary from papulopustules to verrucous plaques with crusted borders (Fig. 64.21).

Coccidioidomycosis

• Due to Coccidioides immitis, a dimorphic fungus that forms arthrospores in the soil and spherules within the skin (see Fig. 64.17D).

• Endemic to the southwestern United States (see Fig. 64.20).

• Cutaneous manifestations: lesions vary from papules to pustules, abscesses, and plaques with sinus tracts (Fig. 64.22).

Fig. 64.22 Coccidioidomycosis. Moist erythematous plaque on the face (A) and multiple papules and suppurative nodules on the arm (B) in two patients living in the southwestern United States.

• Molluscum contagiosum-like lesions may be seen in HIV-infected persons.

Cryptococcosis

• Molluscum contagiosum-like lesions may be seen in HIV-infected patients and other immunocompromised hosts (see Fig. 64.25G), in addition to ulcers and cellulitis (see Fig. 64.25F).

Histoplasmosis

• Due to Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus (see Fig. 64.17B).

• Endemic to the southeastern and central United States and many other countries with reservoirs in birds, including fowl, and bats (see Fig. 64.20).

• Disease contracted through inhalation or, rarely, implantation.

• Immunocompetent hosts: oral ulcers in up to 75% of patients; occasionally cutaneous papulonodules.

• Immunosuppressed hosts: oral ulcers and multiple papules or plaques (Fig. 64.23), including ones that resemble molluscum contagiosum.

Paracoccidioidomycosis

• Cutaneous lesions are primarily periorificial and associated with involvement of the oral mucosa; verrucous and ulcerative plaques are seen (Fig. 64.24).

Opportunistic Pathogens

See Table 64.6 and Fig. 64.25.

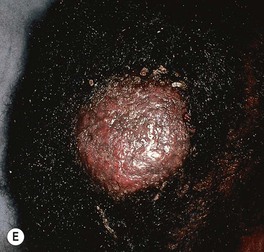

Fig. 64.25 Clinical findings of opportunistic fungal infections in immunocompromised hosts. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis characterized by hyperpigmented plaques with brown-black scale-crusts at the site of intravenous catheters on the arm (A); firm pink papulonodule due to disseminated candidiasis (B); erythematous papulonodule with central necrosis due to embolus of Mucor circinelloides (C); necrotic hemorrhagic bulla due to embolus of Aspergillus flavus (D); cellulitis with area(s) of necrosis due to Rhizopus (E) and Cryptococcus neoformans (F); and crusted molluscum contagiosum-like lesions due to disseminated cryptococcosis (G). C, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; F, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD; G, Courtesy, Athanasia Syrengelas, MD, PhD.

For further information see Ch. 77. From Dermatology, Third Edition.