Chapter 356 Fulminant Hepatic Failure

Etiology

Various hepatotoxic drugs and chemicals can also cause fulminant hepatic failure. Predictable liver injury can occur after exposure to carbon tetrachloride or Amanita phalloides mushroom or after acetaminophen overdose. Acetaminophen is the most common etiology of acute hepatic failure in children and adolescents in the United States and England. In addition to the acute intentional ingestion of a massive dose, a therapeutic misadventure leading to severe liver injury can also occur in ill children given doses of acetaminophen exceeding weight-based recommendations for many days. Such patients can have reduced stores of glutathione after a prolonged illness and a period of poor nutrition. Idiosyncratic damage can follow the use of drugs such as halothane, isoniazid, or sodium valproate. Herbal supplements are additional causes of hepatic failure (see Table 355-2).

Clinical Manifestations

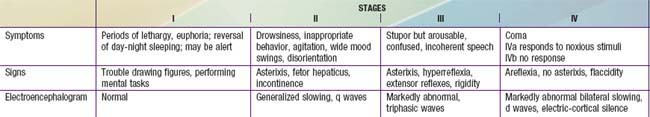

Patients should be closely observed for hepatic encephalopathy, which is initially characterized by minor disturbances of consciousness or motor function. Irritability, poor feeding, and a change in sleep rhythm may be the only findings in infants; asterixis may be demonstrable in older children. Patients are often somnolent, confused, or combative on arousal and can eventually become responsive only to painful stimuli. Patients can rapidly progress to deeper stages of coma in which extensor responses and decerebrate and decorticate posturing appear. Respirations are usually increased early, but respiratory failure can occur in stage IV coma (Table 356-1).

Prognosis

Children with hepatic failure might fare somewhat better than adults, but overall mortality with supportive care alone exceeds 70%. The prognosis varies considerably with the cause of liver failure and stage of hepatic encephalopathy. With intensive medical support, survival rates of 50-60% occur with hepatic failure, complicating acetaminophen overdose (may be as high as 90%) and with fulminant HAV or HBV infection. By contrast, spontaneous recovery can be expected in only 10-20% of patients with liver failure caused by the idiopathic form of acute liver failure or an acute onset of Wilson disease. In patients who progress to stage IV coma (see Table 356-1), the prognosis is extremely poor. Brainstem herniation is the most common cause of death. Major complications such as sepsis, severe hemorrhage, or renal failure increase the mortality. The prognosis is particularly poor in patients with liver necrosis and multiorgan failure. Age <1 yr, stage 4 encephalopathy, an INR >4, and the need for dialysis before transplantation have been associated with increased mortality. Pretransplant serum bilirubin concentration or the height of hepatic enzymes is not predictive of post-transplant survival. Children with acute hepatic failure are more likely to die while on the waiting list compared to children with other diagnoses. Owing to the severity of their illness, the 6 mo post–liver transplantation survival of ~75% is significantly lower than the 90% achieved in children with chronic liver disease. Patients who recover from fulminant hepatic failure with only supportive care do not usually develop cirrhosis or chronic liver disease. Aplastic anemia occurs in ~10% of children with the idiopathic form of fulminant hepatic failure and is often fatal.

Baliga P, Alvarez S, Lindblad A, et al. Posttransplant survival in pediatric fulminant hepatic failure: the SPLIT experience. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1364-1371.

Bass NM, Mullen KD, Sanyal A, et al. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(12):1071-1080.

Bernal W, Auzinger G, Dhawan A, et al. Acute liver failure. Lancet. 2010;376:190-198.

Ciocca M, Ramonet M, Cuarterolo M, et al. Prognostic factors in paediatric acute liver failure. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:48-51.

Dhawan A. Etiology and prognosis of acute liver failure in children. Liver Transpl. 2008;14(Suppl 2):S80-S84.

Emre S, Schwartz ME, Shneider B, et al. Living related liver transplantation for acute liver failure in children. Liver Transpl Surg. 1999;5:161-165.

Garcia-Pagan J, Caca K, Bureau C, et al. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2370-2378.

Grabhorn E, Richter A, Fischer L, et al. Emergency liver transplantation in neonates with acute liver failure: long-term follow-up. Transplantation. 2008;86:932-936.

Kirsch R, Yap J, Roberts EA, et al. Clinicopathologic spectrum of massive and submassive hepatic necrosis in infants and children. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:516-526.

Kortsalioudaki C, Taylor RM, Cheeseman P, et al. Safety and efficacy of N-acetylcysteine in children with non–acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure. Liver Transplant. 2008;14:25-30.

Medical The. Letter: Rifaximin (Xifaxan 550) for hepatic encephalopathy. Med Lett. 2010;52(1350):87-88.

Murray KF, Hadzic N, Wirth S, et al. Drug-related hepatotoxicity and acute liver failure. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:395-405.

Narkewicz MR, Olio DD, Karpen SJ, et al. Pattern of diagnostic evaluation for the causes of pediatric acute liver failure: an opportunity for quality improvement. J Pediatr. 2009;155:801-806.

Savino F, Lupica MM, Tarasco V, et al. Fulminant hepatitis after 10 days of acetaminophen treatment at recommended dosage in an infant. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e494-e497.

Squires RHJr. Acute liver failure in children. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:153-166.

Squires RH, Shneider BL, Bucuvalus J, et al. Acute liver failure in children: the first 348 patients in the pediatric acute liver failure study group. J Pediatr. 2006;148:652-658.

Stravitz RT, Kramer AH, Davern T, et al. Intensive care of patients with acute liver failure: recommendations of the US acute liver failure study group. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2498-2508.