Chapter 3 From 1685 to 2008: An Introduction to Restless Legs Syndrome

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a dysesthesia that is difficult for patients to define. There is a great variability in the wording of its description. Some patients have used phrases such as “water running under my skin” or “a snake inside my legs.” They have described twitching, burning, and irritating sensations. The result of the dysesthesia is an urge to move. The symptom appears nearly exclusively at rest and is at its peak in the evening or early part of the night.

It was very accurately described by Thomas Willis in 1685.1 The dysesthesia disturbing the sleep of patients was characterized as follows:

RLS was once considered to be a form of hysteria. In 1861, Wittmaack2 coined the term anxieties tibiarum. In 1923, Oppenheim3 pointed out that RLS could be described as a neurosis that could be familial or inherited. In 1940, Mussio-Fournier and Rawak4 affirmed the neurological origin of RLS and made the initial observation that RLS was exacerbated during pregnancy; several years later, they re-emphasized that upper limbs may be involved.5

The term “restless legs syndrome” was coined in 1945 by Ekbom,6 who also defined all the clinical features of the syndrome.6,7 He maintained that there was a vascular etiology for the syndrome and recommended vasodilators as treatment. Since that time, the presence of a circulatory disturbance has been investigated. Vasodilators have demonstrated limited therapeutic success, leading some to speculate on a hypersensitivity of peripheral autonomic receptors combined with an abnormal motor response.

In 1962, Menninger-Lerchenthal8 noted that RLS patients commonly had low blood iron levels. He suggested that RLS was an iron metabolism disorder with secondary dysfunction of the pallidonigral system.

In 1965, Lugaresi and colleagues9 investigated RLS patients with the use of polysomnography and noted the presence of short leg jerks during their sleep. These jerks were similar to those observed earlier by Symonds,10 who named the phenomenon “nocturnal myoclonus” and had associated it with an epileptic phenomenon. But Lugaresi and colleagues11 clearly demonstrated in 1968 the absence of any seizure disorder with these jerking movements. These repetitive movements are now called periodic limb movements.

The clinical neurophysiology of RLS is still unclear. Martinelli and Coccagna12 examined H reflexes and polysynaptic lower limb reflexes; they performed repeated stimulations and found that the polysynaptic reflexes failed to cease, persist, or even increase in response. The onset of the reflex may trigger electromyographic activity. These changes were more pronounced in the evening, and the authors interpreted their findings as suggestive of a partial spinal cord disinhibition. In 2000, Bara-Jimenez and colleagues13 found a sleep-related increase in the spinal flexor response on stimulation of the median plantar nerve. They noted a greater diffusion of the reflexes, which suggested some impairment of spinal activity during sleep. Provini and coauthors14 showed that periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) in RLS patients has varying patterns of muscular recruitment and muscle inhibition. This finding was interpreted as being indicative of involvement of different and occasionally unsynchronized generators and led to the hypothesis that there was abnormal hyperexcitability along the spinal cord triggered by sleep-related, supraspinal, and unknown factors. But the clinical neurophysiological investigations in RLS patients are still limited.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) has also been performed in RLS patients by many researchers with varying findings. Provini and coauthors14 reported normal findings, whereas Tergau and colleagues15 and Scalise and collaborators16 observed a reduction in the intracortical inhibition for feet and hands. Varying conclusions were drawn, and it was suggested that there may be an abnormal motor excitability and disinhibition of inhibitory circuits.

Imaging Studies

Imaging studies have been performed on RLS patients17–23 based on treatment response results involving iron and dopaminergic agonists. These studies used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and positron emission tomography (PET). SPECT studies have looked at presynaptic and postsynaptic receptor bindings. Using iodine-123 iodobenzamide (IBZM) binding, Michaud and collaborators23 reported a significant reduction in the postsynaptic median striatal dopamine receptor binding in RLS patients. PET studies are rare and were never performed in the evening; results have been inconclusive to this point. Bucher and colleagues20 performed the early fMRI studies in RLS patients and found an activation in the red nucleus and brainstem close to the reticular formation when patients developed involuntary periodic limb movements; the authors concluded that subcortical generators are involved in RLS. Overall, however, results obtained from imaging studies have been rather limited and mixed. There is a suggestion of mild reductions in the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system, but additional work is needed.

Epidemiology

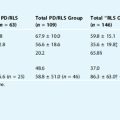

Several epidemiological studies have been performed to evaluate the prevalence of RLS.23–27 These studies reflect an overwhelming predominance of white patients; there is little information on the presence of RLS in patients of different races and ethnicities (see Chapter 7). To be valid, epidemiological studies must involve a representative sample of the general population, but many studies have failed to meet this requirement. Most epidemiological studies were based on the minimum criteria for the diagnosis of RLS (International Classification of Sleep Disorders or International Restless Leg Syndrome Study Group). There are problems with epidemiological studies based on these criteria. For example, some subjects (particularly in the younger age group) may have a complaint that is so intermittent and mild that the presence of the syndrome cannot be recognized. Thus, information on the pediatric population is unknown. Current studies indicate a prevalence of approximately 6% to 7%, with a range between 5% and 9%.24–27

But many questions remain unanswered. For instance, the prevalence in different ethnic groups and in white women (who appear to be affected more often than their male counterparts) still needs to be established. Preliminary studies suggest that Japanese28 and African-American populations are less affected than whites, but the percentage of affected subjects is unknown.

The familial incidence of RLS was noted as early as 1861 by Wittmaak.2 In 1923, Oppenheim3 believed it to be a hereditary disorder. Several groups29–31 have performed familial studies of idiopathic RLS, and the results are concordant, even if percentages differ. There is a clear subgroup of subjects with idiopathic RLS that presents a positive family history. The most recent studies indicate that the frequency of positive family history oscillates between about 40% and 65% of the cases. The highest percentage had been found by a Quebec group.32 This specific group may be of interest, as the French-speaking individuals came from a geographically limited part of France and had a great deal of intermarriage between the families. It is known that groups coming from the area around “Lac Saint Jean” have a larger percentage of familial-specific neuromuscular disorders than do populations from many other places in Canada. Some specific genes may have a greater chance of being present due to these historical conditions, and identification of specific genetic markers may occur earlier there. At the same time, however, the genetic findings may not be completely applicable to other subject groups, and familial cases in other white populations may be less.

Since Ekbom’s studies in the 1940s,6,7 the pattern of inheritance described in familial cases has been assumed to be a Mendelian autosomal dominant mode of inheritance. Montagna and collaborators30 further supported this claim with their extensive familial investigation. Several studies agree that familial cases are recognized at an earlier age than sporadic cases. The unresolved question is which cutoff age to use. This cutoff point varies widely between studies, with a range between 20 and 45 years. In support of the genetic origin of the syndrome, the phenomenon of anticipation (i.e., the evidence of earlier age of onset of the syndrome in successive generations)33,34 has been found in a subset of symptomatic families. Anticipation has been observed in several inherited neurological disorders and is caused by “unstable” mutations. Several linkages have been found, the first found in the French Canadian population.35 It should be noted that linkage studies are difficult to perform and require exact phenotypic definition. More promising may be gene-wide-association studies that have implicated specific variants of three genes related to RLS36 (see Chapter 8). Investigators are rapidly following up on these studies to determine differences in ethnic groups and to develop new pathophysiological investigations.

Treatment

The greatest advances have been made in the treatment of RLS. In 1982, Akpinar37 reported the very successful response to levodopa with benserazide; in 1987,38 he reported a response to other dopaminergic drugs. Guilleminault and colleagues39 were the first to report the negative responses to dopaminergic agents, such as development of symptoms during other periods of the circadian cycle, with appearance of symptoms earlier in the day. A phenomenon known as “augmentation”40 may also occur, in which symptoms are noted to extend beyond the originally affected limbs. It seems that augmentation is seen sooner with levodopa than with other dopaminergic agonists, but it has been reported with all of these compounds.40 Two positive findings have been that a change from one dopamine (DA) agonist to another commonly restores full efficacy of the treatment, and the negative phenomena disappear. After several months of discontinuation, the original drug may return to full efficacy without any evidence of problems (see Chapter 31).

However, patients do not always respond to DA agonists. Another effective treatment option includes the opioids, from codeine to methadone, but caution should be taken, with consideration of related adverse effects (see Chapter 32). Another interesting therapeutic option is the treatment of iron deficiency.41–43 A series of recent studies have emphasized the relation between RLS and a decrease in central nervous system iron,17 particularly in the substantia nigra; cellular changes (inadequate storage and acquisition of iron) have been noted in post-mortem brain tissue analysis (see Chapter 34). Abnormality of the transferrin receptor has been hypothesized. RLS appears with low blood iron and can be corrected with oral iron supplementation in patients with low ferritin. In 1953, Norlander44 reported that intravenous iron infusion could lead to complete remission of the syndrome. Earley and colleagues45 replicated this study and reported that a single intravenous infusion of iron dextran was associated with lasting, beneficial effects, but this experimental study needs to be replicated using double-blind protocols.

1. Willis T. The London Practice of Physic. London: Bassett and Crooke, 1685.

2. Wittmaack T. Pathologie und Therapie der Sensibilitatneurosen. Leipzig: E. Schafer, 1861;459.

3. Oppenheim H, 7. Lehrbuch der Nervenkrankheiten. Berlin: Karger. 1923:1774.

4. Mussio-Fournier JC, Rawak F. Familiares Auftreten von Pruritus. Urtikaria and parasthetischer Hyperkinese der unteren Extremitaten. Confin Neurol. 1940;3:110-114.

5. Mussio-Fournier JC, Rawak F. Agitation paresthesique des extremites. Rev Neurol (Paris). 1947;79:37-41.

6. Ekbom KA. Restless legs. Acta Med Scand. 1945;158(suppl):1-123.

7. Ekbom KA. Asthenia crurum paresthetica (‘irritable legs’). New syndrome consisting of weakness, sensation of cold and nocturnal paresthesia in legs, responding to certain extent to treatment with Priscol and Doryl; note on paresthesia in general. Acta Med Scand. 1944;118:197-209.

8. Menninger-Lerchenthal E. Ruhelosigkeit der Beine (Restless legs, Tachyathetosis). Wien Ztschr Nervenhk 1962;19-62.

9. Lugaresi E, Tassinari CA, Coccagna G, et al. Particularites cliniques et polygraphiques du syndrome d’impatience des membres inferieurs. Rev Neurol. 1965;113:545-555.

10. Symonds CP. Nocturnal myoclonus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1953;16:166-171.

11. Lugaresi E, Coccagna G, Berti-Ceroni G, Ambrosetto C. Restless legs syndrome and nocturnal myoclonus. In: Gastaut H, Lugaresi E, Berti-Ceroni G, Coccagna G, editors. The Abnormalities of Sleep in Man. Bologna: Aulo Gaggi; 1968:285-296.

12. Martinelli P, Coccagna G. Rilievi neurofisiologici sulla syndrome delle gambe senza riposo. Riv Neurol. 1976;66:553-560.

13. Bara-Jimenez W, Aksu M, Graham B, Sato S, Hallett M. Periodic limb movements in sleep: State-dependent excitability of the spinal flexor reflex. Neurology. 2000;54:1609-1616.

14. Provini F, Vetrugno R, Meletti S, et al. Motor pattern of periodic limb movements during sleep. Neurology. 2001;57:300-304.

15. Tergau F, Wischer S, Paulus W. Motor system excitability in patients with restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1999;52:1060-1063.

16. Scalise A, Cadore IP, Gigli GL. Motor cortex excitability in restless leg syndrome. Sleep Med. 2004;5:393-396.

17. Allen RP, Barker PB, Wehrl F, et al. MRI measurement of brain iron in patients with restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2001;56:263-265.

18. Eisensehr I, Wetter TC, Linke R, et al. Normal IPT and IBZM SPECT in drug-naïve and levodopa-treated idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2001;57:1307-1309.

19. Staedt J, Stoppe G, Kogler A, et al. Single photon emission tomography (SPET) imaging of dopamine D2-receptors in the course of dopamine replacement therapy in patients with nocturnal myoclonus syndrome (NMS). J Neurol Transm. 1995;99:187-193.

20. Bucher SF, Seelos KC, Oertel WH, et al. Cerebral generators involved in the pathogenesis of the restless legs syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:639-645.

21. Tribl GG, Asenbaum S, Klosch G, et al. Normal IPT and IBZM SPECT in drug naive and levodopa-treated idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2002;59:649-650.

22. Bucher SF, Trenkwalder C, Oertel WH. Reflex studies and MRI in the restless legs syndrome. Acta Neurol Scand. 1996;94:145-150.

23. Michaud M, Soucy JP, Chabli A, et al. SPECT imaging of striatal pre- and postsynaptic dopaminergic status in restless legs syndrome with periodic leg movements in sleep. J Neurol. 2002;249:164-170.

24. Ulfberg J, Nystrom B, Carter N, Edling C. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome among men aged 18 to 64 years: An association with somatic disease and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Mov Disord. 2001;16:1159-1163.

25. Phillips B, Young T, Finn L, Asher K, et al. Epidemiology of restless leg symptoms in adults. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2137-2141.

26. Ohayon MM, Roth T. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in the general population. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:547-554.

27. Allen RP, Walters AS, Montplaisir J, et al. Restless legs syndrome prevalence and impact: REST General Population Study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1286-1292.

28. Tan EK, Seah A, See SJ, Lim E, Wong MC, Koh KK. Restless legs syndrome in an Asian population: A study in Singapore. Mov Disord. 2001;16:577-579.

29. Ondo WG, Vuong KD, Wang Q. Restless legs syndrome in monozygotic twins: Clinical correlates. Neurology. 2000;55:1404-1406.

30. Montagna P, Coccagna G, Cirignotta F, Lugaresi E. Familial restless legs syndrome: Long-term follow-up. In: Guilleminault C, Lugaresi E, editors. Sleep/Wake Disorders: Natural History, Epidemiology, and Long-Term Evolution. New York: Raven; 1983:231-235.

31. Winkelmann J, Wetter TC, Collado-Seidel V, Gasser T, et al. Clinical characteristics and frequency of the hereditary restless legs syndrome in a population of 300 patients. Sleep. 2000;23:597-602.

32. Montplaisir J, Boucher S, Poirier G, Lavigne G, et al. Clinical, polysomnographic, and genetic characteristics of restless leg syndrome: A study of 133 patients diagnosed with new standard criteria. Mov Disord. 1997;12:61-65.

33. Trenkwalder C, Collado-Seidel V, Gasser T, Oertel WH. Clinical symptoms and possible anticipation in a large kindred of familial restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 1997;11:389-394.

34. Lazzarini A, Walters AS, Hickey K, Coccagna G, et al. Studies of penetrance and anticipation in five autosomal-dominant restless legs syndrome pedigrees. Mov Disord. 1999;14:111-116.

35. Desautels A, Turecki G, Montplaisir J, Sequeira A, et al. Identification of a major susceptibility locus for restless legs syndrome on chromosome 12q. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1266-1270.

36. Winkelmann J, Ferini-Strambi L. Genetics of restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:179-183.

37. Akpinar S. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with levodopa plus benserazide. Arch Neurol. 1982;39:739.

38. Akpinar S. Restless leg syndrome with dopaminergic drugs. Clin Pharmacol. 1987;10:69-79.

39. Guilleminault C, Cetel M, Philip P. Dopaminergic treatment of restless leg and rebound phenomenon. Neurology. 1993;43:445.

40. Ferini-Strambi L. Restless legs syndrome augmentation and pramipexole treatment. Sleep Med. 2002;3(Suppl 1):S23-S25.

41. O’Keeffe ST, Gavin K, Lavan JN. Iron status and restless legs syndrome in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1994;23:200-203.

42. Lee KA, Zaffke ME, Baratte-Beebe K. Restless legs syndrome and sleep disturbance during pregnancy: The role of folate and iron. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:335-341.

43. Earley CJ, Connor JR, Beard JL, et al. Abnormalities in CSF concentrations of ferritin and transferrin in restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2000;54:1698-1700.

44. Nordlander NB. Therapy in restless legs. Acta Med Scand. 1953;145:453-457.

45. Earley CJ, Heckler D, Allen RP. The treatment of restless legs syndrome with intravenous iron dextran. Sleep Med. 2004;5:231-235.