CHAPTER 56 Frequency, urgency and the painful bladder

Introduction

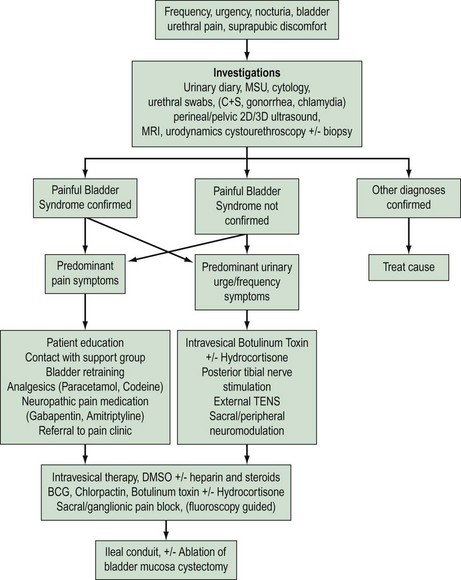

‘Cystitis’ is a term used for irritative urinary symptoms of frequency, urgency, suprapubic pain and dysuria. These symptoms of altered lower urinary tract sensation may be of recent onset (acute), longstanding (chronic) or recurrent. They may be caused by a variety of intravesical pathology such as infection, calculi, drug-induced inflammation, non-infective inflammatory processes due to local [e.g. painful bladder syndrome (PBS)] or systemic conditions (e.g. sarcoidosis), benign or malignant lower urinary tract tumours, or extravesical pelvic pathology such as pelvic masses (e.g. fibroids, endometriosis). Accurate diagnosis, appropriate intervention and therapy requires careful patient evaluation and a sound understanding of the differential causes (Figure 56.1).

Definitions

The Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society (ICS) published a terminology statement on lower urinary tract function in 2002 (Abrams et al 2002a,b). The majority of the following definitions are based on this statement.

24-h frequency is the total number of daytime voids and episodes of nocturia during a 24-h period.

Haematuria is an important symptom that requires urgent evaluation to exclude carcinoma.

Prevalence

A population-based study on the prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms showed that the most commonly reported storage symptom in women is nocturia (54.5%). Urgency occurs in 12.8% and frequency in 7.4% of women. If nocturia is defined as two or more nocturnal micturitions per night, instead of one or more, the prevalence is decreased to 24% (Irwin et al 2006). PBS is a common condition in women, with reported prevalence of 1.7% in those aged under 65 years and 4% in those aged over 80 years. The vast majority of women with PBS have moderate or severe symptoms (Lifford and Curhan 2009).

Aetiology

Irritative bladder symptoms can be caused by a number of conditions originating within the lower urinary tract (Box 56.1). Infection and functional disorders, such as detrusor overactivity or voiding dysfunction, may cause urge symptoms and should be excluded. These conditions should be differentiated from more generalized systemic disorders (e.g. pregnancy, diabetes mellitus, renal disease), pelvic inflammatory disease or gynaecological surgery. A pelvic mass may cause urge-frequency symptoms due to bladder compression.

Box 56.1 Non-infective sensory disorders of the lower urinary tract

The aetiology of PBS is poorly understood. Several theories have been proposed over the years, including infection, immunological factors, leaky urothelium due to glycosaminoglycan deficiency, mast cell activation and altered neural function. Consensus is developing regarding epithelial dysfunction, mast cell activation and neurogenic inflammation; all part of a possible inflammatory response (Elgavish 2009).

Assessment

Investigations

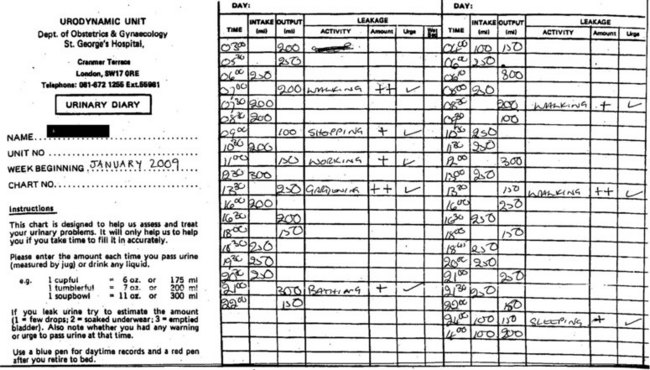

Urinary diary

A detailed 3-day urinary frequency–volume diary is an important part of the initial and ongoing assessment (Figure 56.2). These diaries are more accurate than patient recall, allowing rapid and accurate diagnosis of urinary frequency, nocturia, estimation of voided volumes, functional bladder capacity, and assessment of episodes of urgency, pain and incontinence as well as their temporal relationship. A diary will also educate the patient regarding voiding habits, and is essential for bladder retraining.

Imaging

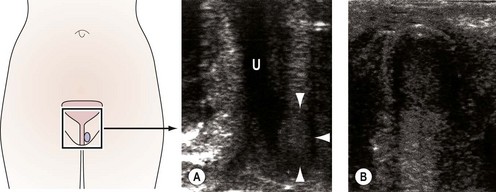

Imaging of the urinary tract can be performed using ultrasound or contrast radiography, either alone or synchronously with urodynamic assessment [videocystourethrography (VCU)]. VCU demonstrates voiding function and can identify urethral obstruction, a urethral diverticulum or external compression due to fibroids or prolapse. Haematuria in the absence of identifiable uropathogens, negative cystoscopy or recurrent UTI is an indication for assessment of the upper urinary tract using contrast intravenous urography or urinary tract ultrasound. Ultrasound can also determine bladder residual volume and bladder wall thickness, and identify any structural abnormalities, including urethral diverticulae (Figure 56.3) (Doumouchtsis et al 2008).

Plain abdominal X-ray will demonstrate 90% of calculi present in the kidney, ureters or bladder due to the presence of calcium or cystine. Computed tomography (urogram or magnetic resonance imaging) may be required to provide accurate imaging of upper and lower urinary tract pathology. The automated bladder ultrasound machine is a simple, inexpensive tool used to measure urinary residual volume. However, it does have relatively poor sensitivity for volumes of less than 100 ml or more than 400 ml. In addition, artefacts may be introduced by the presence of pelvic pathology (e.g. uterine fibroids, pelvic haematoma, ovarian cysts) (Cooperberg et al 2000). The automated bladder ultrasound machine is a useful screening tool in older women with urge-frequency syndrome and/or recurrent cystitis with suspected voiding difficulty.

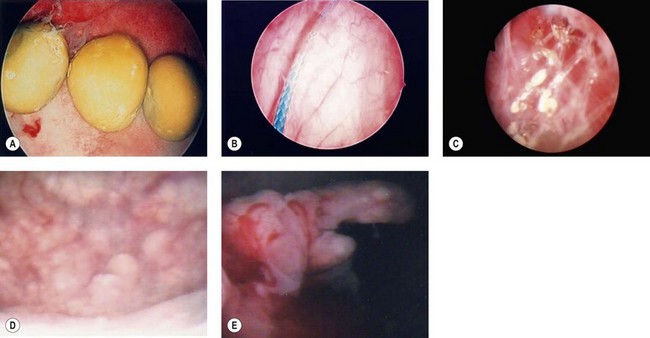

Cystourethroscopy

Evaluation of the lower urinary tract by cystourethroscopy is an essential skill for all gynaecological surgeons, not only in the assessment of urinary symptoms and pain but during pelvic surgery for the prevention and early treatment of bladder and urethral injury. Cystoscopy is undertaken in an inpatient or outpatient setting using a flexible or rigid system. Rigid cystosocopy is well tolerated by women under local anaesthetic in an outpatient setting (Lee et al 2009). Cystoscopy is indicated for haematuria, abnormal urinary cytology, recurrent UTI or persistent symptoms despite conservative treatment. At cystourethroscopy, the lower urinary tract should be carefully visualized using a 70° or 30° scope for the bladder and a 0° scope with Sasche sheath for the urethra. Features such as mucosal trabeculation, bladder diverticula, tumours, squamous metaplasia, bladder calculi and foreign bodies are readily identifiable (Figure 56.4). Women with misplaced intravesical sutures (e.g. colposuspension), eroded mesh following slings for incontinence or grafts for prolapse surgery, exposed urethral bulking agents or sterile abscess (e.g. Zuidex) may present with urgency, bladder pain and/or recurrent UTI. A biopsy should be taken of any suspicious localized lesions to exclude carcinoma.

Treatment

Painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis

The European Society for the Study of Interstitial Cystitis (ESSIC) recently proposed the term ‘bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis’ (van de Merwe et al 2008). Guy Hunner first described this condition in 1914, and the mucosal tearing and fissuring which he described as an ‘ulcer’ carries his name. PBS/interstitial cystitis is a chronic bladder condition seen mainly in women (10 : 1 female:male ratio). The main presenting symptoms are frequency, urgency, nocturia and bladder pain, which often increase as the bladder fills and reduce after micturition. Pain may be experienced in the urethra, loin area and/or perineum. Chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia and dysmenorrhoea are also common symptoms, and coexistence with other causes of pelvic pain (e.g. endometriosis) is well recognized. There are cystoscopic and histological features which are considered typical, but in many cases, the diagnosis is one of exclusion, having ruled out specific causes such as infection and malignancy.

The reported prevalence of PBS/interstitial cystitis varies widely due to different diagnostic criteria. It has been estimated at 18 per 100,000 women in Finland (Oravisto 1975), eight to 16 per 100,000 in the Netherlands (Bade et al 1995), 30 per 100,000 in 1987 in the USA, and 865 per 100,000 women in 1994 in the USA (Rosamilia 2005). Delay between onset of symptoms and diagnosis can be 5–7 years. Leppilahti et al (2005) found that the prevalence of clinically confirmed probable interstitial cystitis in women was 230/100,000 and the prevalence of possible/probable interstitial cystitis was 530/100,000.

The pathophysiology is poorly understood and the condition is considered multifactorial (Nickel 2002). Proposed aetiologies include an infective agent, allergic or autoimmune conditions, ‘leaky’ urothelium secondary to a defective glycosaminoglycan layer, urinary toxins, lymphatic or vascular abnormalities and neurogenic inflammation. Any of these pathological changes may be a result rather than cause of the disease process. Loss of integrity at the epithelial surface of the bladder, secondary to an infective or other inflammatory insult, has been implicated along with sensory nerve upregulation and enhanced mast cell activation (Sant 2002), resulting in regional neuropathy. Other gynaecological and gastrointestinal manifestations may be present, including pain and voiding symptoms (Nickel 2002).

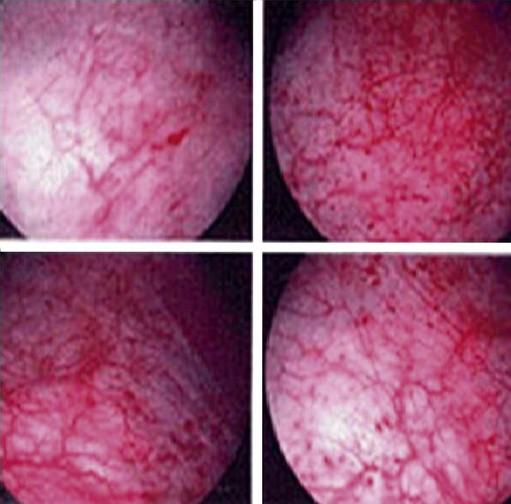

The ESSIC group (van de Merwe et al 2008) proposed that a diagnosis of PBS should be made on the basis of exclusion of confusable diseases and by the recognition of the specific combination of symptoms and signs of PBS. Confusable diseases include carcinoma, infection, urethral diverticulum, prolapse, endometriosis, OAB and pudendal nerve entrapment. Symptoms and signs for use in diagnostic criteria do not need to be specific. On the contrary, if a specific symptom or sign existed for the target disease, a diagnosis would only require the presence of the specific feature, and diagnostic criteria would not be necessary. PBS should be diagnosed on the basis of chronic (>6 months) pelvic pain, pressure or discomfort perceived to be related to the urinary bladder, accompanied by at least one other urinary symptom such as persistent urge to void or frequency. Further classification of PBS is based on findings at cystoscopy using hydrodistension and bladder biopsies. Cystoscopic features accepted as positive signs are glomerulations, Hunner’s lesions or both (Figure 56.5). Hunner’s lesion is ‘a circumscript, reddened mucosal area with small vessels radiating towards a central scar, with a fibrin deposit or coagulum attached. This site ruptures with increasing bladder distension, with petechial oozing of blood from the lesion and mucosal margins in a waterfall manner. A rather typical, slightly bullous edema develops post-distension with varying peripheral extension’. Biopsy findings accepted as positive signs of PBS are inflammatory infiltrates and/or granulation tissue and/or detrusor mastocytosis and/or intrafascicular fibrosis (van de Merwe et al 2008). Only 50% of cases have positive histopathology findings, and the purpose of biopsy is often to exclude malignancy.

Botulinum toxin A has been used in the treatment of PBS with variable results. A Cochrane review on intravesical therapy showed that BCG and oxybutynin are reasonably well tolerated, and evidence is most promising for these. Resiniferatoxin has limited efficacy and causes pain, reducing treatment compliance (Dawson and Jamison 2007). Major urological surgery involving ulcer resection, bladder denervation, and partial or total cystectomy with urinary diversion should be considered as a last resort.

Drug-induced cystitis

The bladder is susceptible to the adverse effects of drugs because of the excretion of several drug metabolites in the urine. A history of present and past medications is important as drug-induced cystitis can occur immediately following administration or may manifest many years later. The term ‘drug-induced cystitis’ is therefore dependent on evidence of the onset of irritative symptoms and inflammatory changes at cystoscopy following drug administration, resolution following withdrawal, and recurrence with readministration of the drug. Implicated drugs include cyclophosphamide, tiaprofenic acid (Surgam), sulphasalazine, fenfluramine, fluoxetine, simvastatin, danazol and a number of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Drugs that cause cystitis should be withdrawn if a patient develops irritative symptoms or haematuria. Adverse effects of cyclophosphamide can be reduced with prophylactic administration of Mesna (2-meracaptoethane sulfonate sodium) and adequate hydration. Mitomycin, doxorubicin or BCG instilled locally to treat bladder tumours can also cause cystitis, contracture and calcification. Their administration should therefore be limited to 1 h/week for a maximum of 8 weeks (Drake et al 1998).

Radiation cystitis

Radiation cystitis may occur as an early or late complication. The bladder can be irradiated intentionally for the treatment of bladder cancer, or incidentally for the treatment of pelvic malignancies. Radiation cystitis is characterized by dysuria and increased urinary frequency (Chuang et al 2008). Acute cystitis is caused by the inflammatory response to radiation, and consists of urgency, frequency, dysuria and haematuria. Chronic cystitis is the end result of the inflammatory process. Ischaemia and fibrosis may result in a small contracted non-functional bladder with severe frequency, urgency and incontinence. Radiation cystitis can range from minor temporary irritative voiding symptoms to severe haematuria, incontinence, fistula formation, necrosis and death. The total single dose, duration of radiotherapy, treatment cycle, preceding surgery, pre-existent infection and previous radiotherapy all influence the risk of radiation cystitis.

Eosinophilic cystitis

Eosinophilic cystitis is a rare inflammatory condition of the bladder which has been associated with allergy, bladder tumours, bladder injury, infections and drugs. It is characterized by the antigen–antibody reaction and probably represents a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction to exogenous allergens. Transmural inflammation of the bladder, predominantly with eosinophils, is followed by fibrosis in the chronic phase. Affected individuals typically have a history of atopy and present with frequency, dysuria, suprapubic pain, haematuria, proteinuria and pyuria. Eosinophiluria occurs in 30% of cases, but up to 50% will have a raised serum eosinophil count. Cystoscopy and biopsy are the gold standard for diagnosis. Medical therapy, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents or steroids, may provide symptomatic relief, but long-term follow-up is mandatory as the lesion tends to recur (Teegavarapu et al 2005).

Proliferative and metaplastic lesions of the bladder

Squamous metaplasia is a well-delineated ‘white patch’ confined to the trigone, and is present in oestrogen-producing women. Keratinizing squamous metaplasia is also known as ‘leukoplakia’. It is generally diffuse and associated with recurrent infection and chronic irritation. It often occurs in association with bladder calculi, urethral diverticula or a foreign body. Macroscopically, the affected areas of the bladder have a thickened white and shiny appearance interspersed with areas of bladder inflammation. Bladder biopsies typically demonstrate mature keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. Its clinical significance remains unclear, but has been linked to the development of invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Both synchronous diagnosis of urothelial tumour and subsequent tumour development on follow-up have been identified. The risk of malignancy is increased in cases with dysplasia as well as extensive keratinization. Lesions should be treated with local transurethral resection. Although dysplasia is considered to be a premalignant condition, there is not enough evidence to identify keratinizing squamous metaplasia of the bladder as premalignant. However, all patients should undergo regular surveillance (Ahmad et al 2008).

Lower urinary tract tumours

Carcinoma in situ (CIS) may be asymptomatic or present with microscopic or gross haematuria, urgency, frequency and dysuria. Diagnosis is often delayed because symptoms are attributed to UTI. More than 50% of patients with CIS have coexistent papillary cancer. Cystoscopic appearance varies from normal to erythema or oedema. Histology usually demonstrates abnormal pleomorphic transitional cells confined to the urothelium. Investigation includes urine cultures for fungi and tuberculosis, and cytology studies. Urine cytology is positive in 80–90% of cases. Intravesical BCG instillation is considered the preferred treatment. Surgical resection with radical cystectomy or ablation using transvesical laser or diathermy are indicated for persistent disease, but recurrence or progression to muscle invasion will occur in more than 40% of these women. Chemotherapy, α-interferon and photodynamic therapy are other treatment options for BCG-refractory cases. Outcomes vary and depend on whether CIS is de novo, secondary or concomitant to papillary bladder cancer (Nese et al 2009).

Urethral diverticulum

Female urethral diverticula are an uncommon variable in presentation, and the diagnosis is sometimes difficult and delayed. They represent an outpouching of the urethral mucosa through a defect of the periurethral fascia, and may be congenital (embryonic cystic remnants) or more commonly acquired. Obstruction of the periurethral glands, infection and subsequent rupture into the urethral lumen may lead to a urethral diverticulum. Weakening of the periurethral fascia following intraurethral trauma (urethral dilatation), continence surgery or childbirth may result in a diverticulum. Diverticula may be asymptomatic or present with a variety of symptoms, including urgency, recurrent cystitis, haematuria, urethral discharge, vaginal pain or dyspareunia (Romanzi et al 2000). Depending on the patency of the diverticular ostium, contents may stagnate, predisposing to infection or abscess in up to 30% of cases (El-Mekresh 2000), calculi in 1.5–10% of cases or metaplasia leading to malignancy. Investigations include cystourethroscopy, retrograde urethrography, magnetic resonance imaging, and high-resolution transvaginal or transperineal ultrasound (Rovner 2007).

Surgical excision is necessary in symptomatic women. The aim of surgical repair is to excise the diverticular wall, close the ostium and repair the periurethral fascial defect in layers without tension to reduce the risk of recurrence or fistula formation. In the presence of a large defect or poor tissue integrity, reinforcement of the repair is required. Autologous pubovaginal slings with rectus abdominis fascia or local vaginal, labial or bladder wall flaps have been used. The Martius labial fat graft uses a sleeve of adipose tissue mobilized from the labia majora, still attached to its vascular pedicle. This is rotated and tunnelled under the skin into the vagina (Leach 1991). Complications of diverticulectomy include stricture or scarring, recurrence, stress incontinence, fistula, sloughing, urethral pain and dyspareunia. Stress incontinence is more common where the diverticular ostium crosses the urethral sphincter.

Urethral syndrome

Urethral syndrome is a non-specific group of lower urinary tract symptoms, which include pain (suprapubic or urethral) with urinary frequency and urgency. The pain is typically exacerbated by micturition. The diagnosis is one of exclusion. Investigations should exclude infectious and non-infectious causes of cystitis, inflammation secondary to trauma, foreign bodies, contact irritation or localized paraurethral lesions (Skene’s abscess, urethral stricture, diverticulum, tumour), and urethral manifestations of systemic disorders (Reiter’s syndrome, Stevens–Johnson syndrome). Cystourethroscopy is necessary to exclude local pathology. An MSU and urethral swab should be performed for microscopy and culture. In women with recent-onset dysuria and frequency (acute urethral syndrome), and an MSU specimen demonstrating pyuria with less than 105 micro-organisms/ml, an infective cause is often identified (Stamm et al 1980). The most common organisms isolated on culture of urinary specimens or urethral swabs include coliforms, C. trachomatis, S. saprophyticus and N. gonorrhoeae. If cultures are negative, empirical antibiotic therapy with doxycycline alone or in combination with a sulphonamide should be considered, and is frequently associated with symptomatic resolution (Latham and Stamm 1984).

Summary

KEY POINTS

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;187:116-126.

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2002;21:167-178.

Ahmad I, Barnetson RJ, Krishna NS. Keratinizing squamous metaplasia of the bladder: a review. Urology International. 2008;81:247-251.

Bade JJ, Rijcken B, Mensink HJ. Interstitial cystitis in The Netherlands: prevalence, diagnostic criteria and therapeutic preferences. Journal of Urology. 1995;154:2035-2037. discussion 2037–2038

Chuang YC, Kim DK, Chiang PH, Chancellor MB. Bladder botulinum toxin A injection can benefit patients with radiation and chemical cystitis. BJU International. 2008;102:704-706.

Cooperberg MR, Chambers SK, Rutherford TJ, Foster HEJr. Cystic pelvic pathology presenting as falsely elevated post-void residual urine measured by portable ultrasound bladder scanning: report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Urology. 2000;55:590.

Dawson TE, Jamison J 2007 Intravesical treatments for painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4: CD006113.

Doumouchtsis SK, Jeffery S, Fynes M. Female voiding dysfunction. Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey. 2008;63:519-526.

Drake MJ, Nixon PM, Crew JP. Drug-induced bladder and urinary disorders. Incidence, prevention and management. Drug Safety. 1998;19:45-55.

El-Mekresh M. Urethral pathology. Current Opinion in Urology. 2000;10:381-390.

Elgavish A. Epigenetic reprogramming: a possible etiological factor in bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis? Journal of Urology. 2009;181:980-984.

Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. European Urology. 2006;50:1306-1314. discussion 1314–1315

Latham RH, Stamm WE. Urethral syndrome in women. Urologic Clinics of North America. 1984;11:95-101.

Leach GE. Urethrovaginal fistula repair with Martius labial fat pad graft. Urologic Clinics of North America. 1991;18:409-413.

Lee JW, Doumouchtsis SK, Jeffery S, Fynes MM. Evaluation of outpatient cystoscopy in urogynaecology. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2009;279:631-635.

Leppilahti M, Sairanen J, Tammela TL, Aaltomaa S, Lehtoranta K, Auvinen A. Prevalence of clinically confirmed interstitial cystitis in women: a population based study in Finland. Journal of Urology. 2005;174:581-583.

Lifford KL, Curhan GC. Prevalence of painful bladder syndrome in older women. Urology. 2009;73:494-498.

Nese N, Gupta R, Bui MH, Amin MB. Carcinoma in situ of the urinary bladder: review of clinicopathologic characteristics with an emphasis on aspects related to molecular diagnostic techniques and prognosis. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2009;7:48-57.

Nickel JC. Interstitial cystitis: characterization and management of an enigmatic urologic syndrome. Reviews in Urology. 2002;4:112-121.

Oravisto KJ. Epidemiology of interstitial cystitis. Annales Chirurgiae et Gynaecologiae Fenniae. 1975;64:75-77.

Romanzi LJ, Groutz A, Blaivas JG. Urethral diverticulum in women: diverse presentations resulting in diagnostic delay and mismanagement. Journal of Urology. 2000;164:428-433.

Rosamilia A. Painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis. Best Practice and Research in Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;19:843-859.

Rovner ES. Urethral diverticula: a review and an update. Neurourology and Urodynamics. 2007;26:972-977.

Sant GR. Etiology, pathogenesis, and diagnosis of interstitial cystitis. Reviews in Urology. 2002;4(Suppl 1):S9-S15.

Stamm WE, Wagner KF, Amsel R, et al. Causes of the acute urethral syndrome in women. New England Journal of Medicine. 1980;303:409-415.

Teegavarapu PS, Sahai A, Chandra A, Dasgupta P, Khan MS. Eosinophilic cystitis and its management. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2005;59:356-360.

van de Merwe JP, Nordling J, Bouchelouche P, et al. Diagnostic criteria, classification, and nomenclature for painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: an ESSIC proposal. European Urology. 2008;53:60-67.