Francisella

1. List the media of choice for optimal recovery and cultivation of Francisella tularensis.

2. Describe the optimal incubation conditions for F. tularensis.

3. Describe the normal habitat and means of transmission of Francisella spp.

4. Describe the symptoms of tularemia and differentiate the various clinical presentations, including ulceroglandular, glandular, oculoglandular, oropharyngeal, systemic (typhoidal), and pneumonic tularemia.

General Characteristics

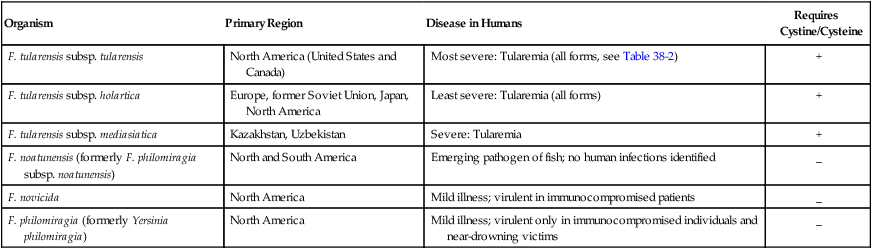

Organisms belonging to the genus Francisella are faintly staining, tiny, gram-negative coccobacilli that are oxidase and urease negative, catalase-positive, nonmotile, non–spore forming, strict aerobes. The taxonomy of this genus continues to be in flux. Current members of the genus share greater than 97% identity based on 16SrRNA sequence analysis. The most current proposed taxonomy is summarized in Table 38-1. For the most part, different subspecies are associated with different geographic regions.

TABLE 38-1

Most Recent Taxonomy of the Genus Francisella and Key Characteristics

| Organism | Primary Region | Disease in Humans | Requires Cystine/Cysteine |

| F. tularensis subsp. tularensis | North America (United States and Canada) | Most severe: Tularemia (all forms, see Table 38-2) | + |

| F. tularensis subsp. holartica | Europe, former Soviet Union, Japan, North America | Least severe: Tularemia (all forms) | + |

| F. tularensis subsp. mediasiatica | Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan | Severe: Tularemia | + |

| F. noatunensis (formerly F. philomiragia subsp. noatunensis) | North and South America | Emerging pathogen of fish; no human infections identified | _ |

| F. novicida | North America | Mild illness; virulent in immunocompromised patients | _ |

| F. philomiragia (formerly Yersinia philomiragia) | North America | Mild illness; virulent only in immunocompromised individuals and near-drowning victims | _ |

Spectrum of Disease

The disease associated with F. tularensis, known as tularemia, is recognized worldwide. In the United States the clinical manifestations have been referred to as rabbit fever, deer fly fever, and market men’s disease. The clinical manifestation depends on the mode of transmission, the virulence of the infecting organism, the immune status of the host, and the length of time from infection to diagnosis and treatment. The typical clinical presentation after inoculation of F. tularensis through abrasions in the skin or by arthropod bites includes the development of a lesion at the site and progresses to an ulcer; lymph nodes adjacent to the site of inoculation become enlarged and often necrotic. Once the organism enters the bloodstream, patients become systemically ill with high temperature, chills, headache, and generalized aching. Clinical manifestations of infection with F. tularensis range from mild and self-limiting to fatal; they include glandular, ulceroglandular, oculoglandular, oropharyngeal, systemic, and pneumonic forms. These clinical presentations are briefly summarized in Table 38-2.

TABLE 38-2

Clinical Manifestations of Francisella tularensis Infection

| Types of Infection | Clinical Manifestations and Description |

| Ulceroglandular | Common; ulcer and lymphadenopathy; rarely fatal |

| Glandular | Common; lymphadenopathy; rarely fatal |

| Oculoglandular | Conjunctivitis, lymphadenopathy |

| Oropharyngeal | Ulceration in the oropharynx |

| Systemic (typhoidal) tularemia | Acute illness with septicemia; 30% to 60% mortality rate; no ulcer or lymphadenopathy |

| Pneumonic tularemia | Acquired by inhalation of infectious aerosols or by dissemination from the bloodstream; pneumonia; most serious form of tularemia |

Laboratory Diagnosis

Specimen Collection, Transport, and Processing

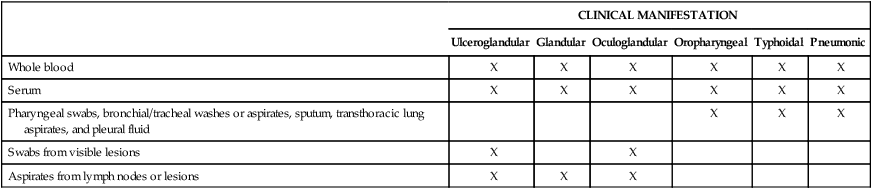

Specimen collection for the identification of F. tularensis is highly dependent on the type of clinical manifestation. A detailed description of the recommended type of specimen associated with the patient’s clinical presentation is presented in Table 38-3. In light of recent events and concerns about bioterrorism, laboratories must keep in mind that isolation of F. tularensis from blood cultures might be considered a potential bioterrorist attack; F. tularensis is considered one of the Select Biological Agents of Human Disease (see Chapter 80).

TABLE 38-3

Recommended Specimen Type Based on Clinical Manifestation

| CLINICAL MANIFESTATION | ||||||

| Ulceroglandular | Glandular | Oculoglandular | Oropharyngeal | Typhoidal | Pneumonic | |

| Whole blood | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Serum | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Pharyngeal swabs, bronchial/tracheal washes or aspirates, sputum, transthoracic lung aspirates, and pleural fluid | X | X | X | |||

| Swabs from visible lesions | X | X | ||||

| Aspirates from lymph nodes or lesions | X | X | X | |||

Approach to Identification

In previous reports, problems have been identified in association with Francisella species isolated from clinical specimens. Twelve microbiology employees were exposed to F. tularensis even though bioterrorism procedures were in place; the organism had been isolated from blood, respiratory, and autopsy specimens and grew on chocolate agar. In this situation, multiple cultures were worked up on open benches without any additional personal protective equipment for what had been thought to be most consistent with a Haemophilus species. As a result of this report, microbiologists must be aware of not only the key characteristics of this group of organisms (Box 38-1), but also the possible pitfalls in their identification (e.g., some strains grow well on sheep blood agar; identification kits may incorrectly suggest an identification of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans). If F. tularensis is suspected, all culture Petri dishes should be taped from the top to the bottom in two places to keep them together for safety purposes.