CHAPTER 65 Forensic gynaecology

Introduction

There seems to be an escalating epidemic of rape globally, and it is known that the majority of sexual assaults are not reported to the police, and domestic or spousal rape is even less commonly reported. Sexual assault is not only a serious criminal justice problem but is also a major public health issue. In the UK, ‘intimate violence’ is a collective term used for partner abuse, family abuse and sexual assault, with ‘sexual assault’ being defined as indecent exposure, sexual threats and unwanted touching (‘less serious’), rape or assault by penetration including attempts (’serious’) by any person including a partner or family member (Roe 2008). Annual figures relating to crime in England and Wales are published as the Home Office Statistical Bulletin, reflecting not only the police recorded crime but also findings from the British Crime Survey (BCS) (Kershaw et al 2008). The BCS is a large victimization survey of approximately 47,000 adults living in private houses in England and Wales. Based on the 2006/07 BCS self-completion module on intimate violence, approximately 3% of women and 1% of men had experienced a sexual assault (including attempts) in the previous 12 months. The majority of these were less serious sexual assaults. A significant minority (40%) of victims of serious sexual assault had not told anyone about their most recent experience, with only 11% informing the police. A further worrying statistic is that for victims of serious sexual assault, 37% were repeat victims. In a three-city comparative study of client violence against prostitutes working from street and off-street locations, 28% of women involved in street-based prostitution reported attempted rape (Barnard et al 2002).

Most rape allegations do not proceed to court; in 1982–1985, 20% of reported cases went to court in Oslo (Bang 1993). In the UK, the conviction rate for all reported cases is currently between 5.7% and 6.5% (Dyer 2008, Williams 2009). The Home Office figures suggest that actual numbers of convictions for rape are increasing year on year, but the increase in convictions is not keeping pace with the increased reporting, thus there is a high level of attrition or case drop-out. Victims who decline to complete the initial investigative process are more likely to do this in areas where there is no sexual assault referral centre (SARC) (Kelly et al 2005). SARCs are widely regarded as the ideal environment for quality forensic examination, ensuring that the victim has access to other services such as sexual health and professional counsellors.

Legal aspects

The SOA 2003 was a significant overhaul of the UK law that dealt with sexual violence, and there are now new offences such as the offence of rape to include oral and anal penetration with a penis, and assault by penetration; penetration may be by part of the defendant’s body but not the penis, or penetration with an object (Rights of Women 2008).

Medical practitioners need to be aware of the legal context in which they gather evidence, and the forensic examination has a dual purpose: firstly, to address the immediate needs and concerns of women; and secondly, the justice system’s need for the documentation of physical findings, the rigorous collection and preservation of evidence, an interpretation of the findings, and provision of expert opinion in legal proceedings (Kelly and Regan 2003).

Her Majesty’s Government have indicated that they have strengthened the capacity of specialist rape prosecutors and rape coordinators to ensure that the best case is built, and expanded special measures to make it easier for vulnerable victims to give evidence (H.M. Government 2007). Indeed, the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999 legislation gives vulnerable and intimidated witnesses the opportunity to give evidence from behind screens, by video link or for the court to be cleared.

Reasons for failure to report sexual assault

The most important barriers to reporting rape and sexual assault are:

Attrition

Attrition in sexual offences cases refers to cases dropping out from the time of initial complaint to the trial. There is an increasing justice gap for victims as the increasing number of convictions for rape is not keeping pace with the increased reporting (H.M. Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate 2007). Attrition during investigations begins early. Two significant factors were identified by the review of the handling of investigations by the police and Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate, one of which is the decision by the victim not to complete the initial process. The other factor was the decision to withdraw support for the investigation or prosecution (H.M. Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate 2007).

Sexual Assault Referral Centres

In early 2009, there were 24 SARCs in England and Wales, the main client group being complainants of recent sexual assault and where the victim has access to a range of agencies including health, the services of counsellors and trained volunteers (H.M. Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate 2007). The UK Home Office has indicated that SARCs should have the infrastructure to support ongoing victim care, and there should be adequate training and development and quality assurance. There should also be evidence of operational and management policies and procedures (Home Office 2005). It is important that despite the need for cleanliness in the examination room, there are separate interview rooms with a calming and relaxing feel about them (Kelly and Regan 2003).

The services that SARCs provide include:

The clinical requirements of the SARC include:

Consenting to a medical and forensic examination

In achieving consent for a forensic examination, it is important to remember the principles of confidentiality. The General Medical Council (GMC) indicate that ‘Patients have a right to expect that information about them will be held in confidence by their doctors’, accepting that doctors may have contractual obligations to third parties, such as in their work as police surgeons, and in such circumstances, disclosure may be expected (General Medical Council 2006). In such circumstances, the GMC recommends that the doctor is ‘satisfied that the patient has been told at the earliest opportunity about the purpose of the examination and/or disclosure, the extent of the information to be disclosed and the fact that relevant information cannot be concealed or withheld’.

The complainant may agree to a ‘qualified consent’ (i.e. to the release of information to the prosecution without allowing scrutiny by the defence). If she does not consent to release of the medical details, the examiner may be ordered to disclose information by a judge, in which case the forensic physician (FP) should only disclose information relevant to the request for disclosure. In the ‘Disclosures to courts or in connection with litigation’ section of the GMC document ‘Confidentiality: Protecting and Providing Information’, it is stated ‘You should object to the judge or the presiding officer if attempts are made to compel you to disclose what appear to you to be irrelevant matters’ (General Medical Council 2004). The section continues, ‘You must not disclose personal information to a third party such as a solicitor, police officer or officer of a court without the patient’s express consent’.

Examination of the complainant of sexual assault

The forensic examination may provide vital evidence that identifies the assailant and/or supports the complainant’s account should the case come to court. Not only does the forensic examination itself increase the likelihood of legal action, but having a forensic examination doubles the likelihood of prosecution (McGregor et al 2002, Kelly and Regan 2003).

Who should undertake the examination?

In ideal circumstances, the victim of sexual assault should be allowed to choose the gender of the examining doctor. In the 1980s, the gender of the examining physician was not always felt to be a factor affecting the victim’s response to the medical examination (Hockbaum 1987), but recent evidence shows that most victims (male and female) prefer female staff; 43.5% of victims said that they would not continue the forensic examination if the doctor was male (Chowdhury-Hawkins et al 2008).

Training in sexual assault examination

Few doctors have received formal training in the principles of clinical forensic medicine.

To ensure optimal care for the victims of sexual assault, a coordinated multidisciplinary approach should be made to tackle the theoretical and practical training issues. Local and national programmes have been developed at all levels, from specialist registrars through to continuing medical education of those actively involved in rape examination. Subspecialist gynaecology trainees in sexual and reproductive health are expected to compete the forensic and domestic violence competencies module as part of their subspecialty training, which emphasizes the importance of preserving evidence and maintaining the evidence chain whilst providing appropriate sexual and reproductive health care for the complainants of sexual assault (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2009).

The examining doctor

The examining doctor must be objective and non-judgemental, and must avoid giving even the smallest cues of suspicion or disbelief which may heighten the victim’s anxiety and emotional trauma, and cause a spiralling decline as her guilt and shame increase and her story is shaken (Dupré et al 1993).

Forensic examination is time-consuming and often lasts in excess of 2 h. A speedy response from the forensic examiner is, however, essential for evidential purposes and victim comfort. The importance of examination within 24 h was emphasized in a study on the outcome of sexual assault victims who pursue legal action (Wiley et al 2003). The characteristics positively associated with a legal outcome included:

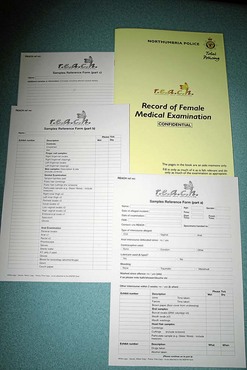

The Record of Forensic Examination

Documentation

Complainant and SARC personnel information

Consent

General medical examination

The Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine (FFLM) has reminded forensic examiners about the importance of recording and measuring injuries caused by teeth, and that a full description and overall dimensions should be documented (Rowlinson et al 2008).

Colposcopic examination

Colposcopic examination is known to increase the positive genital findings compared with inspection of the genitalia. A study of 200 cases of sexual assault examined with a colposcope revealed positive findings in 32% on inspection; however, the positive findings increased to 87% with colposcopic examination (Sommers 2006). Where forced digital penetration is alleged, colposcopy has been found to be particularly useful (Rossman et al 2004).

Questions have been raised regarding why photocolposcopic examination of AGI in a sexually assaulted child is considered the ‘gold standard’ of examination, yet gross visualization is the standard procedure in adult examination (Brennan 2006). A possible explanation is that colposcopy is seen as an invasive procedure which is ethically unacceptable.

The significance of some of the genital findings during the colposcopic examination remains controversial, especially when images are interpreted by inexperienced clinicians (Templeton and Williams 2006).

Forensic sampling

The forensic evidence collected during the examination is used to help to:

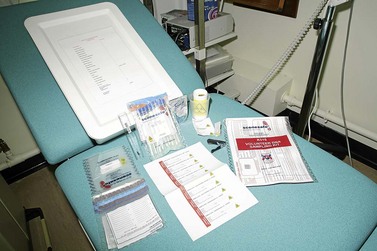

The FFLM has produced a guideline for good practice regarding collection of forensic specimens which is updated at 6-monthly intervals (Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine 2008a). Most SARCs/police forces will have access to a ‘sample reference form’ (Figure 65.3), with tables listing the forensic samples with their corresponding exhibit number, sample description etc. Recent evidence has shown that positive forensic results are achieved in approximately 38% of forensic examinations (McGregor et al 2002).

Postexamination arrangements

Photographs of injuries

Where there is complex skin trauma, photography may act as an adjunct to the description to the findings. It has been claimed that a carefully observed, well-documented description of any injury or group of injuries is worth many photographs (Bunting 1996). Others claim that a photograph can be worth a thousand words if the assailant is claiming consent and the attorney has pictures of the victim with a black eye or worse (Ledray 1993).

Referral to counselling services

At best, a follow-up rate of 31% was achieved in a sexual assault follow-up evaluation clinic, despite efforts to encourage female victims to use the clinic (Holmes et al 1996) (Figure 65.4). Our ability to reduce the occurrence of the long-term effects of sexual assault is limited by the low rates of reporting and lack of focused follow-up for those who do report their assault. However, the doctor can significantly enhance the uptake of counselling in the aftermath of an assault.

Sexually transmitted infections

The frequency of STIs in victims of sexual assault is difficult to estimate due to the low reporting and follow-up of victims. In Mexico, the frequency of STIs was 20% amongst 213 patients (Martinez et al 1999).

Clients are offered referral to a genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinic, where they are seen for screening for STIs 10–14 days after the assault to allow for incubation of newly acquired infection (Home Office 2005). If, however, there are no SARC facilities for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis screening, the client should be seen in the GUM clinic as soon as possible, preferably within 72 h. Where the complainant declines referral, the forensic examiner should recommend antibiotic prophylaxis against gonorrhoea and chlamydia.

HIV testing and hepatitis screening

The risk of acquiring HIV and hepatitis B following rape in the UK is rare and is estimated to be approximately 0.1–0.2% for vaginal rapes and 1–2% for anal rapes for HIV in developed countries (Kelly and Regan 2003). HIV risk assessment should be carried out, assessing the type of assault and enquiring about additional factors which increase or decrease risk (trauma, breech of hymen, condom usage), together with an appraisal of known or overt risk factors to do with the assailant (Home Office 2005).

Postexposure prophylaxis, if given, should be started as soon as possible after sexual assault as it is unlikely to be beneficial after 72 h. The Clinical Effectiveness Group of the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV have updated the UK guideline for the use of postexposure prophylaxis for HIV after sexual exposure (PEPSE), facilitating calculation of the risk of HIV infection after potential exposure, recommending when PEPSE would and would not be considered. It is believed that transmission of HIV is likely to be increased following aggravated sexual intercourse (anal or vaginal) such as occurs during sexual assault, and the authors recommend that clinicians should consider recommending PEPSE more readily in such situations where the ‘source’ individual’s HIV status is unknown (Fisher et al 2006).

Injuries

Non-genital injury

The majority of female victims (40–88%) will have some form of physical injury, although most will be of a minor nature (Bowyer and Dalton 1997, McGregor et al 2002, Palmer et al 2004). Less than 5% of complainants attending SARCs require hospital admission for treatment (Home Office 2005). Where a clinical injury extent score was applied to rate the physical severity of the assault in 113 cases of sexual crime, the injuries were ranked as:

Genital injury

The overall incidence of genital injury is of the order of 20–49% (McGregor et al 2002, Palmer et al 2004, Drocton et al 2008). Genital injury in the absence of non-genital injury is rare (3%) (Palmer et al 2004). Palmer et al also found that risk factors for genital injury were:

Clinical injury extent scoring

McGregor et al devised a clinical injury extent scoring, categorizing injuries as none, mild, moderate or severe, based upon observed genital and extragenital injury (McGregor et al 1999). Criteria for clinical injury scoring were devised; for example, one of the criteria for a moderate injury score was ‘injury or injuries expected to have some impact on function’. The results supported the hypothesis that there is an association between the laying of charges and the presence of documented moderate or severe injury. These findings were supported by a subsequent study where a gradient association was found for genital injury extent score and charge filing, but an injury extent score defined as severe was the only variable significantly associated with conviction.

Genital trauma associated with forced digital penetration has been found in 81% of complainants (Rossman et al 2004). This retrospective study documented the frequency and type of injury in 53 women in whom forced digital penetration was the only reported type of assault. The mean number of genital injuries was 2.4, and 56% of the injuries occurred at four sites: the fossa navicularis, labia minora, cervix and posterior fourchette. The most common types of injury were erythema (34%), superficial tears (29%) and abrasions (21%).

Forensic examiners remain unsure about why some sexual victims display acute injury while others do not (Drocton et al 2008). The potential reasons for these differential findings among female victims were explored for 3356 complainants, of whom 49% displayed AGI. Significant increased risk for AGI was noted with vaginal penetration or attempted penetration using penis, finger or object, and anal-penile penetration. Victims less likely to display AGI were those with a longer postcoital interval and those with increased parity.

The Influence of Alcohol- and Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault

The true extent of alcohol- and drug-facilitated sexual assault (DFSA) is not known and is difficult to estimate, but drugs and alcohol do impair the recollection of events surrounding the sexual assault, making identification and prosecution of the assailant even more difficult. The SOA 2003 states that voluntary intoxication affects a woman’s capacity to choose. The BCS also noted that a significant minority of victims report that they were under the influence of drink in the most recent incident of sexual assault they had experienced (Kershaw et al 2008). Alcohol is also known to be a factor involved in 34% of rape cases reported to the police (Kelly et al 2005). The proportion of DFSA in four American localities was estimated with urine and hair specimens tested for 45 drugs (Juhascik et al 2007). Of 144 subjects, 43% were characterized as DFSA. There was considerable under-reporting of the use of drugs by the subjects.

A study into the nature of DFSA in England examined samples from 120 cases of sexual assault (Operation Matisse 2006). One hundred and nineteen of the 120 victims reported drinking alcohol; however, alcohol was only detected in 62 (52%) cases. In 22 of the 62 (35%) cases, blood alcohol at the time of the incident was estimated to be greater than or equivalent to 200 mg% (i.e. more than twice the driving limit of 80 mg%). The authors commented that a combination of drugs and alcohol exacerbates intoxication, and suggested that some of the cases could be opportunistic DFSA (i.e. where an assailant assaults a victim who is profoundly intoxicated by her own action), whereas other offenders facilitate sexual assault by administering drugs, including alcohol, to the victim.

Description of Wounds

The doctor examining a complainant of sexual assault may experience difficulty with the nomenclature when describing wounds, and may be daunted by the medicolegal significance of the lesions. Even more difficulty may be encountered when asked to give an opinion as to how they may have been caused. The following classification has been adapted from Crane (1996).

Bruises

Factors to remember about bruising

A study into the ageing of bruises determined that the only reliable fact is that bruises with a yellow colour are more than 18 h old, and that the appearance of the other colours is less reliable (Langlois and Gresham 1991).

The following observations should be recorded for each bruise:

Absence of Genital Injury

The absence of genital injuries should not negate an allegation of sexual assault/rape, but the presence of genital injury is thought to carry more weight in obtaining a successful conviction. In a retrospective view of case records of women from Northumbria Police area, only 22 of 83 women had genital injuries (27%) (Bowyer and Dalton 1997). It was concluded that the ‘absence of genital injury should not be used as pivotal evidence by the police or CPS’. Similar incidence of genital injury was reported in a study of 440 cases of reported sexual assault, where 16% of the victims had visible genital injury (Cartwright et al 1986). By the same token, absence of genital injury in no way implies consent by the victim nor the absence of vaginal penetration by the assailant (Cartwright et al 1986).

Reasons for absence of genital injury

Reasons for absence of genital injury may include:

A common tactic of the barrister defending a suspect in a rape trial is not to deny that sexual intercourse between their client and the complainant took place, but rather to claim that she consented to the encounter (Cartwright et al 1986). The defending barrister may also point out to the FP and jury that there are no injuries to the victim’s genitalia, and may ask the doctor how a victim of an alleged rape could escape injury unless, of course, she actually consented to intercourse, highlighting how unimpressive a case may look where there is absence of injury. Cartwright et al found that 75 victims in a review of 440 cases of reported rape showed objective evidence of non-compliance (injuries to non-genital sites) and vaginal penetration (sperm in the vagina), and only 28% of these women had sustained genital injury.

The Statement

Medical witness statement

The minimum requirement for a doctor’s (professional) statement is in the form of a ‘witness to the fact’ document providing a basic interpretation of the findings alone. The FFLM has recommended that all FPs should have training in the production of a factual statement, and should have ongoing support with writing statements from experienced FPs (Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine 2008b).

Interpretation of findings

It is important to comment upon whether appearances of the genital area are normal or abnormal.

Conclusions

Use of relevant references

The absence of genital injuries should not negate an allegation of sexual assault or rape, but it does make it more difficult to prove to a jury as the presence of genital injury is thought to carry more weight in obtaining a successful conviction. With reported rates of visible genital injury being of the order of 20–49%, it is important that the examining doctor is able to quote published data to support the statement that the absence of genital injury does not imply consent by the complainant, and that the presence of genital injury should not be required to validate an allegation of sexual assault (Cartwright et al 1986, McGregor et al 2002, Palmer et al 2004, Drocton et al 2008).

Patterns of Injury

Patterns

Some female survivors of sexual assault sustain more physical injuries than others, and factors influencing the type of injury include the complainant’s skin fragility. Genital trauma is more common in older women (Ramin et al 1992). Where there are multiple bruises, it is essential to undertake a collective assessment of both the bruises and any other surrounding injury in an attempt to reconstruct events. It is also important to recognize particular patterns of injury (e.g. finger-tip bruising consisting of a row or a pair of circular or oval bruises, suggesting the blunt force of gripping associated with resistance in areas such as the upper arms, breasts and legs).

Postmenopausal women

One of the factors influencing the type of injury sustained is the victim’s age. Postmenopausal women only represent a small percentage of the number reporting sexual assault: 2.2% in Dallas County between 1986 and 1991 (Ramin et al 1992). There was no significant difference in the relative proportion of women experiencing non-genital injuries; trauma in general occurred as frequently in the older woman (67%) as in the younger group. This was confirmed in a later study on the effects of age and ethnicity on physical injury from rape (Sommers et al 2006).

Genital trauma is more common: 43% in the postmenopausal group compared with 18% in younger women (Ramin et al 1992). Almost one in five older women had genital lacerations. Other authors have reported an increased frequency of genital injuries in the older victim of sexual assault, and being aged over 40 years has been identified as a risk factor for genital injury (Cartwright et al 1986, Palmer et al 2004). However, no significant association between age and genital injury was found by Sommers et al (2006).

Where there is an increased genital trauma rate, it is presumably due to postmenopausal atrophy causing increased genital tissue susceptibility. It is sad to reflect that older victims tend to live alone, are often robbed and are more likely to be raped by a stranger (Tyra 1993).

Adolescent victims

A pre-existing relationship between a victim and the assailant may explain other elements that distinguish an adolescent victim from her adult counterpart (Muram et al 1995). An assessment of the epidemiology and patterns of AGI in a group of adolescents (13–17 years old) compared with women over 17 years of age showed that adolescents were more likely to be assaulted by an acquaintance or relative (Jones et al 2003).

Weapons and physical force are used less frequently where adolescent victims are involved, but alcohol and drug use is prevalent in adolescent victims (47% of cases) (Muram et al 1995). There are conflicting opinions about the frequency of physical, non-genital injuries in adolescents compared with older victims of sexual assault, but a recent study showed that adolescent victims were less likely to experience non-genital injuries than adults but had a greater frequency of AGI (Jones et al 2003). Common sites of injury in adolescents were posterior, including fossa navicularis, labia minora, fourchette and hymen, whereas for adults, there was a less consistent pattern of AGI, although they did have fewer hymenal injuries and greater injury to the perianal area.

A significant association has been found between race (Black vs White) and genital injury, where Whites were four times as likely as Blacks to have genital injury (Sommers et al 2006). The reasons for this disparity appear to be complex, and the simple explanation of skin colour explaining race/ethnic difference in injury prevalence may suffice for the forensic examiner. However, health disparities may affect the reporting of genital injuries amongst women of colour in the USA.

Vulnerable Women

Mental health

It is important that all the professionals involved with victims of sexual assault recognize that the assault may be followed by rape-related PTSD. This is a debilitating psychiatric condition that can occur in people who experience extremely stressful or traumatic life events, and sexual assault is thought to be one of the most traumatic stressors in life. It is believed that victims attending for forensic examination may already be in the acute phase of PTSD, exhibiting shock, disbelief, anger and possibly memory blocking. The risk of PTSD among female victims of sexual assault is 2.9 times higher compared with women who reported no history of sexual assault, according to a cross-sectional telephone survey of 1769 adult female residents in Virginia (Masho and Ahmed 2007).

A high background prevalence of mental health problems and deliberate self-harm was found in a study of 121 complainants of sexual violence at The Haven, Whitechapel (Campbell et al 2007). When mental health problems were identified, additional questions were asked. Of the female victims, 8% had learning difficulties, 21% had a past history of deliberate self-harm and 20% had a psychiatric history. Three percent of the female victims required immediate referral to the psychiatric liaison team. One must not forget that vulnerable people are at increased risk following sexual violence; indeed, a high frequency of PTSD is seen in female refugees who allege torture (Asgary et al 2006, Edston and Olsson 2007, Hooberman et al 2007).

Women with disabilities

Very few studies have examined how sexual assault patterns differ for women with disabilities, and whether a woman’s disability status influences the degree and nature of the sexual violence. Study data derived from the initial encounter of 16,672 women survivors of sexual assault in Massachusetts from 1987 to 1995 showed that more than 10% of survivors reported one or more disability (Nannini 2006). Among women with a single disability, a survivor who delayed seeking services for 6 months or more was more likely to have a mental health disability. Women with disabilities have been shown to have four times the odds of experiencing sexual assault in the past year compared with women without disability, according to a study in North Carolina (Martin et al 2006). A retrospective longitudinal study of 6273 non-institutionalized women participating in the National Violence Against Women survey in the USA found that women with disabilities that severely limit activities of daily living are four times more likely to be sexually assaulted than women with no reported disability (Casteel et al 2008).

There are even fewer studies concerning refugees who allege that they have been sexually assaulted as victims of torture. In Sweden, the records of 63 female victims of torture were studied (Edston and Olsson 2007). Rape, often both anal and vaginal, several times and by different persons, was reported by 76% of the women. Physical abuse by use of blunt force was alleged by 95%. In a study in the USA, 89 asylum seekers/torture survivors from 30 countries were assessed in an urban primary care clinic, and 7% of cases alleged that rape was the means of abuse (Asgary et al 2006). The authors point out that physicians evaluating torture survivors should be trained in identification and documentation of torture. This is particularly important where sexual violence as a means of torture is alleged.

Migrant women

In the UK, migrant women may be reluctant to seek help and advice, or approach the criminal justice authorities if they perceive that their immigration status might be put at risk by coming forward. In addition, such women may not be aware of the interpreter services that exist for women seeking help with health-related problems. Worldwide, the higher vulnerability of migrant women to sexual abuse and violence is known to place them at risk of STIs and mental health problems associated with sexual violence. Migrant women face sexual abuse by employers in receiving countries, and from personnel in refugee camps (Carballo et al 1996). Migration also fuels the sex tourism industry in countries as diverse as the Netherlands and Thailand.

Court Proceedings

Expert witnesses in sexual assault

Medical evidence is an important factor in the prosecution of rape offences, but it is felt that its evidential worth is not always properly understood by the prosecution. ‘It is vital that the quality of the expert evidence relied upon to support the investigation and prosecution of rape is sound. If it is flawed then challenge by the Defence is inevitable’ (H.M. Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate 2007). The FFLM believes that expert evidence should only be sought from FPs who have gained a postgraduate qualification in clinical forensic medicine.

Expert witness statement

The FFLM recommend that all FPs should annotate their professional statements with ‘this is a professional witness statement of fact. I am able/unable to provide expert opinion evidence in relation to this matter/and would be happy to do so on supply of all relevant documents’ (Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine 2008b).

It is recognized that an important factor in the development of expertise is the building of case experience, and so within the REACH organization, it has been established that an ‘expert’ forensic examiner is one who has examined 20 rape/sexual assault cases and has been actively involved as a FP for at least 2 years. In addition, the expert will have undertaken appropriate training and be an ‘accredited’ FP. The term ‘accredited FP’ implies that the doctor is willing and able to provide an expert statement. An ‘accredited FP’ is under no obligation and the provision of an expert opinion is optional to those experienced enough to do so. Such a two-tier system may prove costly, but with UK conviction rates running at approximately 6.5%, this novel approach may assist the CPS in their assessment of the strength of a particular case (McGregor et al 2002).

Conclusion

Alempijevic D, Savic S, Pavlekic S, Jecmenica D. Severity of injuries among sexual assault victims. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 2007;14:266-269.

Asgary RG, Melatlios EE, Smith CL, Paccione GA. Evaluating asylum seekers/torture survivors in urban primary care: a collaborative approach at the Bronx Human Rights Clinic. Health and Human Rights. 2006;9:164-179.

Bang L. Rape victims — assaults, injuries and treatment at a medical rape trauma service at Oslo Emergency Hospital. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care. 1993;11:15-20.

Barnard MA, Hurt G, Benson C, Church S. Client Violence Against Prostitutes Working from Street and Off-street Locations: a Three-city Comparison. Swindon: Economic and Science Research Council; 2002.

Bowyer L, Dalton ME. Female victims of rape and genital findings. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;104:617-620.

Brennan PA. The medical and ethical aspects of photography in sexual assault examination: why does it offend? Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine. 2006;13:194-202.

Bunting R. Clinical examination in the police context. In: McLay WDS, editor. Clinical Forensic Medicine. London: Greenwich Medical Media; 1996:59-73.

Campbell L, Keegan A, Cybulska D, Forster G. Prevalence of mental health problems and deliberate self-harm in complainants of sexual violence. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 2007;14:75-78.

Carballo M, Grocutt M, Hadzihasanovic A. Women and migration: a public health issue. World Health Statistics Quarterly — Rapport Trimestriel de Statistiques Sanitaires Mondiales. 1996;49:158-164.

Cartwright PS, Moore RA, Anderson JR, Brown DH. Genital injury and implied consent to alleged rape. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 1986;31:1043-1044.

Casteel C, Martin SL, Gurka KK, Kupper LL. National study of physical and sexual assault among women with disabilities. Injury Prevention. 2008;14:87-90.

Chowdhury-Hawkins R, McLean I, Winterholler M, Welch J. Preferred choice of gender of staff providing care to victims of sexual assault in sexual assault referral centres (SARCs). Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 2008;15:363-367.

Crane J. Injury. In: McLay WDS, editor. Clinical Forensic Medicine. London: Greenwich Medical Media; 1996:143-162.

Drocton P, Sachs C, Chu L, Wheeler M. Validation set correlates of anogenital injury after sexual assault. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2008;15:231-238.

Dupré AR, Hampton HL, Morrison H, Meeks GR. Sexual assault. Obstetrical and Gynaecological Survey. 1993;48:640-648.

Dyer C. Rape cases: police admit failing victims. The Guardian. Available at www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2008/mar/04/ukcrime.law, 2008.

Edston E, Olsson C. Victims of torture. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine. 2007;14:368-373.

Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine. Guidelines for the Collection of Forensic Specimens from Complainants and Suspects. Available at www.fflm.ac.uk, 2008.

Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine. Forensic Physicians as Witnesses in Criminal Proceedings. Available at www.fflm.ac.uk, 2008.

Fisher M, Benn P, Evans B, Poznaik A, Jones M, MacLean S, Davidson O, Summerside J, Hawkins D. BASHH Guideline. UK Guideline for the use of post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV following sexual exposure. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2006;17:81-92.

General Medical Council. Disclosures to courts or in connection with litigation. In: Confidentiality: Protecting and Providing Information. London: GMC; 2004. Available at www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/current/library/confidentiality.asp

General Medical Council. Relationships with patients — confidentiality. In: Good Medical Practice. London: GMC; 2006.

General Medical Council. Acting as an Expert Witness. London: GMC; 2008. Available at www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_ethicalguidance/expert_witness_guidance.asp

H.M. Government. Cross Government Action Plan on Sexual Violence and Abuse. London: Home Office; 2007.

H.M. Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate. Without Consent. A Report on the Joint Review of the Investigation and Prosecution of Rape Offence. London: HMIC; 2007.

Hockbaum SR. The evaluation and treatment of the sexually assaulted patient. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 1987;5:601-622.

Holmes MM, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Best CL. Rape-related pregnancy: estimates and descriptive characteristics from a national sample of women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;175:320-325.

Home Office. Medical Care Following Sexual Assault: Guidelines for Sexual Assault Referral Centre. London: Home Office; 2005.

Hooberman JB, Rosenfeld B, Lhewa D, Rasmussen A, Keller A. Classification of torture experiences of refugees living in US. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2007;22:108-123. Available at www.crimereduction.homeoffice.gov.uk/sexualoffences/sexual03.htm

Jones JS, Rossman L, Wynn BN, Dunnock C, Schwatz N. Comparative analysis of adult versus adolescent sexual assault: epidemiology and patterns of anogenital injury. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2003;10:872-877.

Juhascik MP Negrusz A, Faugno D, Ledray L, Greene P, Lider A, Haner B, Gaensslen RE. An estimate of the proportion of drug-facilitation of SA in 4 US localities. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 2007;52:1396-1400.

Kelly L, Regan L. Good Practice in Medical Responses to Recently Reported Rape, Especially Forensic Examinations. A Briefing Paper for the Daphne Strengthening the Linkage Project. London: Child and Woman Abuse Studies Unit, London Metropolitan University; 2003.

Kelly L, Lovett J, Regan L. A Gap or a Chasm: Attrition in Reported Rape Cases. Home Office Research Study 293. London: Home Office; 2005.

Kershaw C, Nicholas S, Walker A, editors. Crime in England and Wales. Home Office Statistics Bulletin 07/08. London: Home Office Research Development and Statistics, Home Office, 2008.

Langlois NEI, Gresham GA. The ageing of bruises: a review and study of the colour changes with time. Forensic Science International. 1991;50:227-238.

Ledray L. Sexual assault nurse clinician: an emerging area of nursing experience. AWHONN’s Clinical Issues. 1993;4:180-190.

Martin SL, Ray N, Sotres-Alvarez D, Kupper LL, Moracco KE, Dickens PA, Scandlin D, Gizlice Z. Physical and sexual assault of women with disabilities. Violence against Women. 2006;12:823-837.

Martinez AH, Villanueva LA, Torres C, Garcia LE. Sexual aggression in adolescents. Epidemiologic study. Ginecologia y Obstetricia de Mexico. 1999;67:449-453.

Masho SW, Ahmed G. Age at sexual assault and posttraumatic stress disorder among women: prevalence, correlates and implications for prevention. Journal of Women’s Health. 2007;16:262-271.

McGregor MJ, Grace L, Marion SA, Wiebe E. Examination for sexual assault: is documentation of physical injury associated with the laying of charges? A retrospective cohort study. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1999;160:1565-1569.

McGregor MJ, Du Mont J, Myhr TL. Sexual assault forensic medical examination: is evidence related to successful prosecution? Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2002;39:639-647.

Muram D, Hostetler BR, Jones CE, Speck PM. Adolescent victims of sexual assault. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1995;17:372-375.

Nannini A. Sexual assault patterns among women with and without disabilities seeking survivor services. Women’s Health Issues. 2006;16:372-379.

Operation Matisse. Investigating Drug Facilitated Sexual Assault. ACPO. Available at www.acpo.police.uk/asp/policies/Data/operation%20Matisse, 2006.

Palmer CM, McNulty AM, D’Este C, Donovan B. Genital injuries in women reporting sexual assault. Sexual Health. 2004;1:55-59.

Ramin SM, Satin AJ, Stone IC, Wendel GD. Sexual assault in postmenopausal women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1992;80:860-864.

Rights of Women. From Report to Court. A Handbook for Adult Survivors of Sexual Violence. London: Aldgate Press; 2008.

Roe S. Intimate violence. In: Kershaw C, Nicholas S, Walker A, editors. Crime in England and Wales. Home Office Statistics Bulletin 07/08. London: Home Office Research Development and Statistics, Home Office, 2008.

Rossman L, Jones JS, Dunnock C, Wynn BN, Bermingham M. Genital trauma associated with forced digital penetration. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2004;22:101-104.

Rowlinson C, Ritchie G, Nicholson F, Wall IF. Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine in conjunction with the British Association for Forensic Odontology Recommendations. Management of Injuries Caused by Teeth. Available at www.fflm.ac.uk, 2008.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Sexual and Reproductive Health Subspecialty Curriculum Module 3. Forensic and Domestic Violence Competencies. RCOG. Available at www.rcog.org.uk/curriculum-module/sexual-reproductive-health-srh-0, 2009.

Sommers MS, Zink T, Baker RB, Fargo JD, Porter J, Weybright D, Schafer JC. Effects of age and ethnicity on physical injury from rape. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 2006;35:199-207.

Templeton DJ, Williams A. Current issues in the use of colposcopy for examination of sexual assault victims. Sexual Health. 2006;3:5-10.

Tyra PA. Older women: victims of rape. Journal of Gerontology Nursing. 1993;19:7-12.

Wiley J, Sugar N, Fine D, Eckert LO. Legal outcome of sexual assault. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;188:1638-1641.

Williams R. Conviction rates for rape remain appallingly low. The Guardian. Available at www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2009/mar/27/rape-convictions-rates, 2009.