85 Foot and Ankle Injuries

• Most ankle sprains are due to inversion during plantar flexion of the ankle, and 85% involve the lateral ligaments.

• Isolated injury to the medial (deltoid) ligament is uncommon; such injury is usually associated with a medial malleolar fracture.

• Examination techniques that cause pain make complete examination less feasible; do not start the examination at the point of maximal swelling and tenderness.

• Because magnetic resonance imaging is better at detecting ligamentous injuries involving the ankle, stress testing is less commonly performed in the acute phase of injury.

• Do not mistake subluxating peroneal tendons for an ankle sprain because the treatment and prognosis are different.

• The Thompson test to assess Achilles tendon rupture can be misleading, especially with partial tears.

• Dislocations at the level of the tibiotalar joint require prompt anatomic reduction to minimize cutaneous and neurovascular injury.

• Talar dome fractures are often missed; further evaluation is required in patients with swelling or locking of the ankle 4 to 5 weeks after injury.

Epidemiology

Inversion injuries may at first glance appear to be common and minor. A large percentage of these injuries continue to be symptomatic for a year or longer after the injury. Chronic instability eventually develops in some individuals and requires surgical repair.1

Pathophysiology

Anatomy

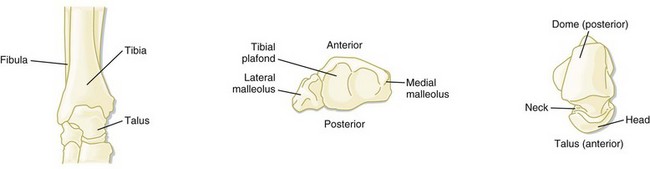

The ankle is composed of two joints: the talar mortise and the subtalar joint. The talar joint is a modified hinge joint similar to a “mortise and tenon,” as referred to in carpentry. It is composed of three bones: the tibia, the mortise, and the talus of the fibula, which form the tenon (Fig. 85.1). The plafond or “ceiling” of this joint is formed by the tibia with its medial malleolus and articulation with the fibula.

The dome of the talus has a trapezoidal shape—wider anteriorly and narrower posteriorly. This anatomic shape confers greater stability in dorsiflexion. However, when the ankle moves into plantar flexion, the narrow part of the talus sits in the mortise, which results in ankle instability and predisposes it to injury.2,3

Ligaments of the Ankle

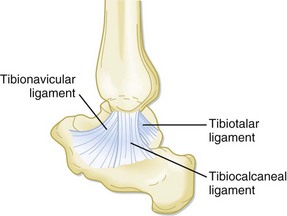

The medial side of the ankle is supported by the deltoid ligament (Fig. 85.2). The deltoid ligament has five components: one deep and four superficial. The deep ligament attaches to the tibia and the undersurface of the talus. The superficial ligaments are the tibionavicular, anterior talotibial, calcaneotibial, and posterior talotibial.

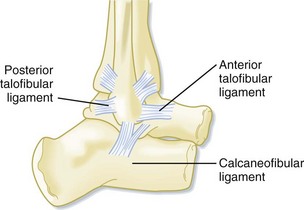

The lateral aspect of the ankle has three supporting ligaments: the anterior talofibular, calcaneofibular, and posterior talofibular (Fig. 85.3). The tibiofibular ligaments include the anterior and posterior inferior ligaments, which bind the distal ends of the tibia and fibula, and the superior ligaments of the same name, which bind the tibia and fibula at the proximal articulation. Other supporting structures are the inferior transverse ligament and the interosseous ligament. The latter is not part of the ankle but nevertheless provides a strong bond between the tibia and fibula.2,3

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Most ankle sprains are due to inversion during plantar flexion of the ankle. Thus approximately 85% of injuries involve the lateral ligaments: the anterior talofibular ligament, the calcaneofibular ligament, and the posterior talofibular ligament. Of sprains caused by inversion, 65% are isolated to the anterior talofibular ligament. In some patients the subtalar complex may also be injured. The calcaneofibular ligament is rarely injured in isolation. Classification of these injuries and examination findings are presented in Table 85.1.

| TYPE OF INJURY | EXTENT OF INJURY | PHYSICAL FINDINGS |

|---|---|---|

| Grade I | Stretch of the ligament with microscopic but not macroscopic tearing | Minor swelling but no joint instability |

| Grade II | Involves partial tearing of the particular ligament | Minor to moderate swelling and some instability of the affected ankle |

| Grade III | Involves complete rupture of the ligament | Significant swelling, tenderness, and ecchymosis; instability of the joint and inability to bear weight |

Isolated injury to the medial (deltoid) ligament is uncommon, and such injury is usually accompanied by a medial malleolar fracture. Distal tibiofibular syndesmotic rupture is very rare and is associated with forceful dorsiflexion and external rotation.2,4

History and Physical Examination

A methodic approach to elicitation of the history of the injury and examination of the ankle joint is of paramount importance. Frequently, the mechanism is unknown because of the sudden and rapid occurrence of the injury. Specific questions about the mechanism, time of the injury, ability to bear weight, and previous history of injury involving the affected joint are helpful in arriving at an accurate diagnosis (Box 85.1).

Box 85.1 Suggested Questions During the History in Patients with Ankle Injuries

The physical examination (Box 85.2) should be thorough and orderly with the intent of assessing joint stability and possible neurovascular compromise. The emergency physician (EP) should make sure that the patient is in a comfortable position for the examination. Many times patients are examined in hallways while sitting in chairs with their feet resting on the floor or a wheelchair footrest. Uncomfortable approaches to examination of the ankle—or any joint for that matter—are detrimental to the welfare of both the patient and physician. All that is derived from this approach is an incomplete examination and an uncomfortable patient and physician.

Box 85.2 Sequential Examination of the Injured Ankle

4. Midshaft tibia and interosseous membrane

5. Medial malleolus and deltoid ligament

6. Lateral malleolus and ligaments

8. Anterior talofibular ligament

10. Posterior talofibular ligament

13. Navicular and bifurcated ligament

14. Base of the fifth metatarsal

16. Other maneuvers (anterior drawer, tilt, side-to-side tests)

The EP should make sure that the patient is seated at a level higher than the examiner (e.g., seated on a gurney with the affected limb dependent, seated on the examining table with both extremities on the table). Never begin the examination at the point of maximal swelling and tenderness. The examination should begin with visual inspection to assess the degree of swelling and the presence of any deformity and discoloration. The neurovascular status of the extremity is evaluated by testing sensation, capillary refilling, and presence of pulses. Once a preliminary assessment is done, the EP should proceed in detail from distal to proximal in an orderly fashion as noted in Box 85.2.5

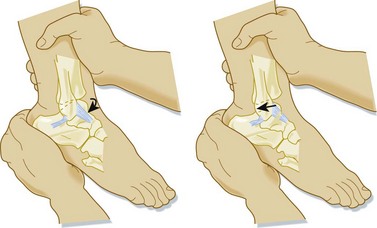

Other Maneuvers

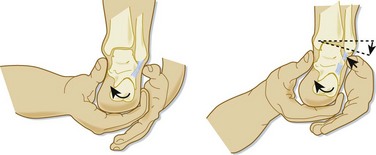

Other maneuvers sometimes used in the evaluation of an injured ankle are worth mentioning. The anterior drawer test (Fig. 85.4) is used to determine the integrity of the anterior talofibular ligament. It is, unfortunately, not very reliable, especially in acute injuries with significant swelling and pain. It is performed by holding the foot at the calcaneus with one hand while the other hand stabilizes the extremity at its middle third. The foot is moved forward while one observes or feels (or both) for displacement of the foot and ankle anteriorly.

The talar tilt test can be used to assess the deltoid ligament and the calcaneofibular ligament by applying eversion and inversion stress, respectively. The calcaneus is held in one hand while the examiner moves the ankle into inversion or eversion (Fig. 85.5). Frequently, it is accompanied by simultaneous radiographic evaluation to determine the amount of tilt at the level of the talus.2

Stress testing is not generally performed in the acute phase of an injury because of its inaccuracy and the pain that it inflicts on the patient. Since the advent of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which can reveal soft tissue injuries of varying degrees, stress testing is rarely used at all.2

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Classification of Ankle Sprains

Subluxation of the Peroneal Tendons

The peroneus longus and brevis tendons lie in a shallow groove immediately posterior to the distal end of the fibula. Rupture of the superior peroneal retinaculum results in subluxation or dislocation of the peroneal tendons. This injury is often mistaken for a common sprain in the emergency department (ED). However, it differs in that the pain and swelling are located along the posterior border of the lateral malleolus. It results from forced dorsiflexion with reflex contraction of the peroneal muscles. Patients complain of pain and a snapping sensation over the posterolateral aspect of the ankle with weakness of eversion.6

Achilles Tendon Injuries

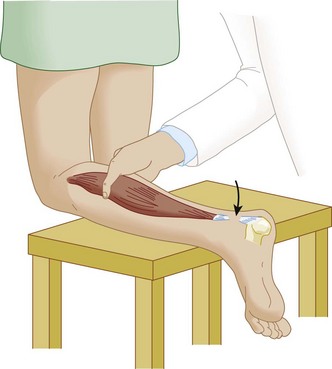

Physical examination reveals swelling and tenderness, as well as a partial or complete defect in the tendon. A positive Thompson test is diagnostic. It is performed by having the patient lie prone on a gurney or stand with the knee of the affected leg resting on a chair (Fig. 85.6). The examiner then squeezes the calf muscles. Individuals with normal Achilles tendons will plantar flex as the maneuver is performed.3

Classification of Fractures

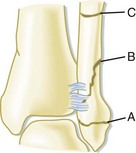

Several classifications of ankle fractures have been published over the years in an effort to facilitate accurate description and subsequent treatment. The most comprehensive classification, still in use, was proposed by Lauge-Hansen in 1950 and was based on cadaver experiments involving the use of foot position (supination or pronation) and direction of the force exerted on the joint (external rotation, adduction, or abduction) at the time of the injury. The Danis-Weber Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (AO) classification proposes a simpler description based on the location and appearance of the fibular fracture. The fracture lines are designated A, below the syndesmosis; B, at the level of the syndesmosis; and C, above the syndesmosis (Fig. 85.7).

The Orthopedic Trauma Association has since expanded the Danis-Weber classification by keeping the three types (A, B, and C) and adding nine groups (1, 2, and 3 for each type) and 27 subgroups.3

In 1987, Tile recommended another classification that identifies ankle fractures by their stability. Because unstable fractures require a different treatment approach than stable fractures do, such distinction is clinically important. For example, identification of a medial injury will generally determine the stability of the ankle joint. Therefore, always suspect an unstable fracture of the ankle when the medial structures are identified as injured clinically or radiographically.4,7

Danis-Weber Classification System

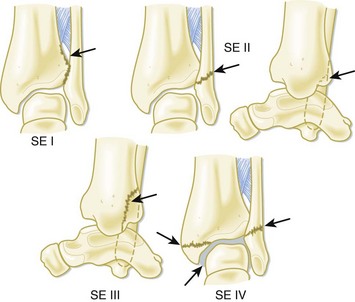

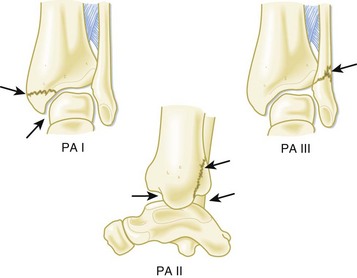

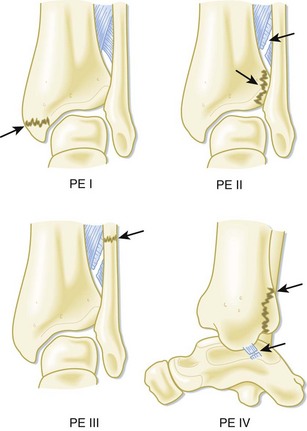

This classification system has four injury patterns: (1) supination adduction (SA or Weber A), (2) supination external rotation (SE or Weber B), (3) pronation abduction (PA or Weber C1), and (4) pronation external rotation (PE or Weber C2). The names of these injury patterns can be thought of in simple terms as indicating the initial position of the foot (supination or pronation) and the direction of the injuring force acting through the talus (adduction, abduction, external rotation). The location and type of fibula fracture are the key to understanding the classification.2

Supination Adduction (SA, Weber A)

Supination (inversion) of the foot and application of an adducting force on the talus result in two sequential injuries: transverse fracture of the lateral malleolus below or up to the level of the tibiofibular joint and a ligament tear (SA I). As the force progresses, the talus impacts the medial malleolus and causes an oblique medial malleolar fracture (SA II) (Fig. 85.8).

Supination External Rotation (SE, Weber B)

This is the most common mechanism of a “twisted ankle” injury. Supination of the foot and application of an external rotation force on the talus result in up to four sequential injuries (Fig. 85-9): tear of the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (SE I); short oblique fracture of the fibula (SE II), which is best seen on a lateral radiograph; fracture of the posterior malleolus (SE III); and transverse fracture of the medial malleolus (SE IV) or a tear of the deltoid ligament (or both).

Pronation Abduction (PA, Weber C1)

In this injury, pronation (eversion) of the foot and application of an abducting force on the talus result in up to three sequential injuries (Fig. 85.10). First, a transverse fracture of the medial malleolus occurs (PA I), and then as the forces progress, the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament tears (PA II). Finally, further abduction of the talus results in an oblique fracture of the distal end of the fibula (PA III). This fibula fracture ends just above the level of the joint line and is best seen on an anteroposterior (AP) or mortise view.

Pronation External Rotation (PE, Weber C2)

In pronation external rotation, pronation (eversion) of the foot and application of an external rotation force through the talus result in up to four sequential injuries (Fig. 85.11). Similar to the pronation abduction mechanism, the first two injuries are the same: transverse fracture of the medial malleolus (PE I), followed by a tear of the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (PE II). The third injury is a short spiral or oblique fracture, usually 6 to 8 cm above the syndesmosis but possibly as high as the midshaft level (PE III). The fourth injury is fracture of the posterior malleolus (PE IV).

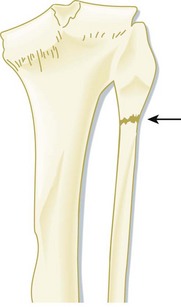

Maisonneuve Fracture (Weber C3)

The exact mechanism leading to a Maisonneuve fracture is not clear. It appears to combine different forces and possibly shifting foot positions. Patients have isolated medial ankle tenderness and swelling. On further examination, tenderness at the level of the proximal end of the fibula is also identified. This fracture is unstable and warrants clinical and radiographic evaluation of the entire lower extremity below the knee. It often goes unrecognized and is identified merely as “just another ankle sprain.” Therefore, vigilance must be exercised when a medial ankle injury is identified in any patient. These medial ankle injuries could be limited to the deltoid ligament, an isolated fracture of the posterior tibial tubercle, or a medial malleolar fracture in the absence of a lateral malleolar fracture. The classic appearance of the injury is a fracture of the neck of the fibula—either linear or comminuted (Fig. 85.12). Emergency orthopedic consultation is necessary.4

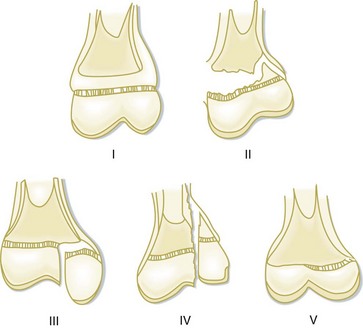

Salter-Harris Classification System

Injuries to the ankle in the pediatric population generally occur at the level of the bone physis. The Salter-Harris classification system enables definition of the type and severity of the fracture. Salter-Harris fractures are generally broken down into five categories as shown in Figure 85.13 and Table 85.2.5

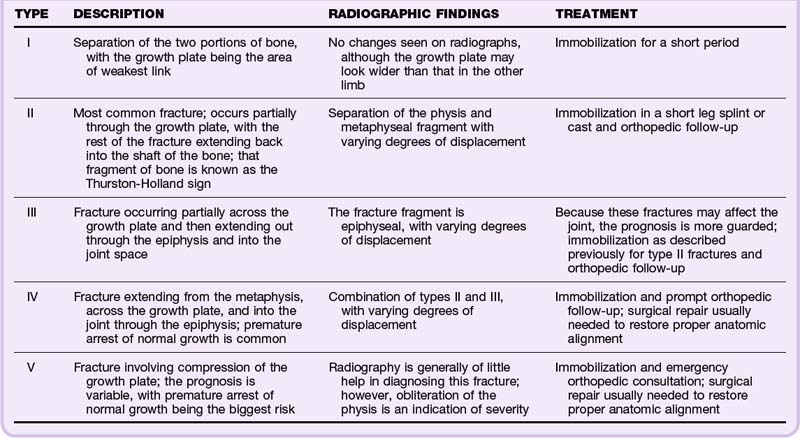

Triplane Fractures

This type of fracture is generally seen in older children with partially closed epiphyses and resembles a Salter-Harris type IV fracture. The mechanism is usually external rotation. Even with proper care and reduction, this fracture can result in epiphyseal growth arrest and deformity. If unsure of the fracture lines on plain film radiographs, computed tomography (CT) is recommended to ascertain the position of the fracture fragments (Fig. 85.14).

Dislocations

The second type is subtalar dislocation. This injury occurs at the level of the talocalcaneal and talonavicular joints. Subtalar dislocations can be medial or lateral, depending on the direction of the foot and the effecting forces. These high-energy injuries result from sports (basketball and baseball), as well as from motor vehicle accidents and falls from heights.6

Foot Injuries

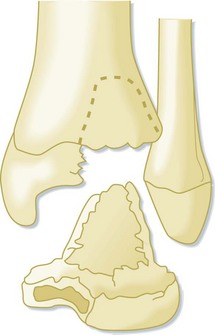

Osteochondritis Dissecans (Osteochondral Fracture)

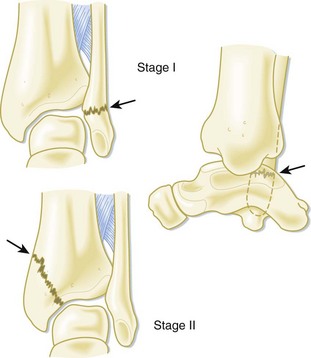

These fractures result from a mechanism similar to that of ankle sprains. When the ankle is forcibly inverted while in plantar flexion or dorsiflexion, the dome of the talus is compressed against the fibula or the tibial plafond. This results in several degrees or “stages” of lesions (Fig. 85.15). More often than not, the initial radiographs are negative, and diagnosis will require CT or MRI. The diagnosis is missed in 40% to 50% of patients seen in the ED with an ankle injury. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is warranted with these injuries, especially if the patient has experienced reinjury, chronic swelling, or locking of the ankle 4 to 5 weeks after the injury.2

Calcaneal Injuries

The most common extraarticular fracture is a calcaneal body fracture. In decreasing frequency, other locations of calcaneal fractures are at the anterior process, the superior tuberosity, and the area of the sustentaculum tali; isolated injuries are rarely seen at these sites. Calcaneal fractures are infrequently encountered as open fractures. Open injuries are reported to occur in only 2% of cases. As a result of the accompanying mechanisms and forces related to calcaneal fractures, other pathology such as spinal injuries and extremity fractures are usually associated with injuries to the os calcis. Multiple complications such as gait abnormalities, arthritis, and leg length discrepancy are generally the sequelae of calcaneal fractures.8

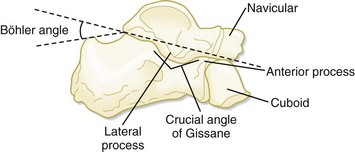

One method of assessing the integrity of the calcaneus is measurement of the Böhler angle. This angle is normally 30 to 35 degrees and is determined by tracing two lines on a lateral view of a radiograph of the foot (Fig. 85.16). One line is drawn from the posterior tuberosity to the apex of the posterior facet. A second line connects the apex of the posterior facet to the anterior (beak) process. An angle of 20 degrees or less should raise suspicion for a compression fracture of the calcaneus.3

Another less frequently used angle measurement is the crucial angle of Gissane. This angle is formed by the downward portion of the posterior facet where it connects to the upward portion. This angle normally measures 100 degrees.3

Other Tarsal Conditions

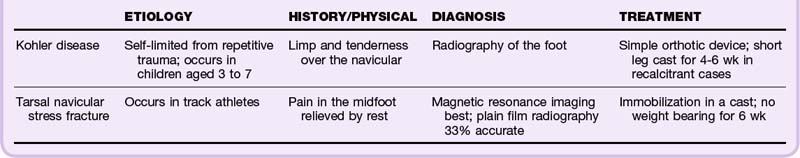

Avascular necrosis occurs in many areas of the skeleton. The foot is not spared, with the tarsal navicular experiencing the greatest frequency of this condition. Stress fractures can result in avascular necrosis when they go unrecognized and untreated.8 Examples of these injuries, with a description of the clinical findings, diagnosis, and treatment, appear in Table 85.3.

Lisfranc Injury

A Lisfranc injury is uncommon and generally associated with significant force. Physical examination reveals significant swelling and tenderness of the midfoot area commensurate with the magnitude of the injury. On occasion, ecchymoses of the midarch area of the foot are present and are diagnostic of this injury. The vasculature should be scrutinized carefully, especially if the intercommunicating arterial branch between the dorsalis pedis artery and the plantar arterial arch has been disrupted. It can lead to a compartment syndrome, which requires prompt intervention by an orthopedic surgeon.8

Metatarsal Injuries

Metatarsal Fractures

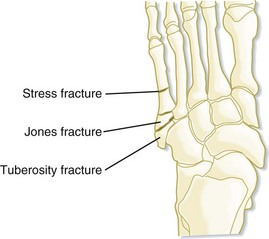

Three types of fractures commonly occur in the proximal fifth metatarsal (proximal to distal): tuberosity avulsion fracture, Jones fracture, and proximal diaphysial stress fracture. Each has distinct characteristics, and the approach to treatment is often controversial. Nevertheless, most of these fractures heal with immobilization over a period of 3 to 8 weeks, depending on location. Treatment of displaced intraarticular fractures, delayed union, and nonunion usually requires operative methods. A Jones fracture has a high rate of nonunion and may require surgical intervention. Patients must be warned of this potential problem. Tuberosity fractures and Jones fractures must not be confused despite their proximity on the fifth metatarsal (Fig. 85.17).3,9

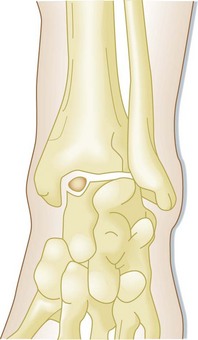

Sesamoid Bone Fractures

The foot has many sesamoid bones. However, those most commonly injured are in the area of the great toe and occasionally in the os trigonum located posterior to the posterior tubercle of the talus. These fractures are infrequent and often go unrecognized. They can occur as a result of direct and indirect trauma. Direct traumatic injuries result from crush-type mechanisms such as falling from a height or direct impact with an external object. Indirectly, the great toe suffers a hyperdorsiflexion-type injury that results in the fracture. In the case of the os trigonum, plantar flexion is the mechanism. Ballet dancers suffering from these injuries may at some time require removal of the bone because of chronic pain.3

Treatment is directed at protection and immobilization of the affected area in either a walking cast or boot for 4 to 6 weeks.3

Toe Fractures

Treatment is directed at anatomic integrity and immobilization. Therefore, reduction of displaced fractures with “buddy tape” immobilization is the standard. All other fractures that are not displaced warrant immobilization in the same fashion; a hard-soled cast shoe is recommended until the pain resolves, at which time an athletic shoe can be worn. In the event of a large intraarticular fracture fragment or significant displacement of the fragments, emergency orthopedic consultation is required.8

Plantar Fasciitis

Treatment consists of ice massage and gentle stretching of the fascia. The latter is accomplished by stretching of the Achilles tendon, as well by rolling the foot back and forth over an object such as a can of soup. An orthotic device is helpful for individuals with excessive pronation on ambulation. Physical therapy in the form of massage and ultrasonography is sometimes necessary. Steroid injections can occasionally be used but should be done judiciously.5

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

Shooting pain distally may be elicited when the entrapped nerve is percussed (Tinel sign). Nerve conduction velocity studies are helpful in obtaining a definitive diagnosis. The multiple causes of tarsal tunnel syndrome are listed in Box 85.3.

Diagnostic Testing

Imaging

Stress views are sometimes helpful but are not presently used as much as in the past. A posteroanterior or mortise view is obtained while stressing the affected ligaments (lateral ligaments) to ascertain the degree of instability as identified by talar tilt. Comparison with the uninjured ankle is necessary, and joint stability is defined as less than 5 degrees of difference between the injured and uninjured sides. A tilt angle greater than 15 degrees with respect to the uninjured side often signifies rupture of the anterior talofibular and calcaneofibular ligaments.2

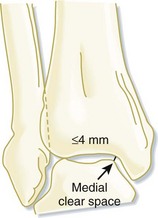

Another radiographic method of assessing ankle joint stability is identification of the medial clear space. This is the distance, as measured on a mortise view, between the lateral border of the medial malleolus and the medial border of the talus. Any value greater than 4 mm is considered abnormal and is a sign of instability (Fig. 85.18).3

Fig. 85.18 Distance between the tibial surface and the medial wall of the fibula.

Any measurement greater than 4 mm is considered abnormal and a sign of instability.

Ottawa Ankle Rules

In an effort to decrease the number of ankle radiographs used in the diagnosis of acute ankle injuries, Stiell et al. from the Ottawa Civic and the Ottawa General Hospitals in Canada conducted a prospective study that included more than 750 patients seen in the ED with acute blunt ankle injuries. They determined that ankle films were necessary only when patients with pain near the malleoli exhibited one or more of the findings shown in Box 85.4.

Likewise, for injuries to the foot, radiographs would be necessary only with pain in the midfoot area and with bone tenderness at the navicular, the cuboid, or the base of the fifth metatarsal.11

Treatment

In general, the approach to treatment of foot and ankle injuries is directed at protecting the affected limb from further injury at the same time that other modalities, including early mobilization, are used. Box 85.5 outlines a brief summary of the standard and basic treatment of these injuries.

Box 85.5 ICEMM Mnemonic for Treatment of Fractures of the Foot and Ankle

ICE: Every 2 hours or as needed for the first 24 to 48 hours

COMPRESSION: Compression dressing (Webril or Ace) to decrease swelling; ankle stirrup to lend stability, if indicated

MOBILIZATION: Early, as soon as patient is pain free

MEDICATION: Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or narcotics when applicable

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

For weekend and other athletes, depending on age and conditioning, Box 85.6 outlines some guidelines when sports activities can be resumed safely.

Anderson RB, Hunt KJ, McCormick JJ. Management of common sports-related injuries about the foot and ankle. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18:546–556.

Davis KW. Imaging of pediatric sports injuries: lower extremity. Radiol Clin North Am. 2010;48:1213–1235.

Hanlon DP. Leg, ankle and foot injuries. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:885–905.

Khan W, Oragui E, Akagha E. Common fractures and injuries of the ankle and foot: functional anatomy, imaging, classification and management. J Perioper Pract. 2010;20:249–258.

Scott AM. Diagnosis and treatment of ankle fractures. Radiol Technol. 2010;81:457–475.

1 Garrick JG. The frequency of injury, mechanism of injury, and epidemiology of ankle sprains. Am J Sports Med. 1977;56:241–242.

2 Canale TS. Ankle injuries. 10th ed. Daugherty K, Jones L, eds. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2003;vol. 3:2131.

3 Marsh JL, Saltzman CL. Ankle fractures. 5th ed. Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, eds. Fractures in adults. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001;vol. 2.

4 del Castillo J, Geiderman JM. The Frenchman’s fibular fracture (Maisonneuve fracture). JACEP. 1979;8:404–406.

5 Trojian TH, McKeag DB. Ankle sprains: expedient assessment and management. In: Howe WB, ed. The physician and sports medicine, vol. 26. New York: Vendome Group; 1998. No. 10

6 Sammarco GJ. Peroneal tendon injuries. Orthop Clin North Am. 1994;25:135–145.

7 Lauge-Hansen N. Fractures of the ankle: combined experimental-surgical and experimental roentgenologic investigations. Arch Surg. 1950;60:957–985.

8 Einhorn TA, Tornetta P, III. Foot and ankle. In: Thordarson DB, ed. Orthopaedic surgery essentials. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:243.

9 Lawrence SJ, Botte MJ. Jones’ fractures and related fractures of the proximal fifth metatarsal. Foot Ankle. 1993;14:358–365.

10 Simons SM. Foot injuries of the recreational athlete. Phys Sportsmed. 1999;27:57–70.

11 Stiell IG, Greenberg GH, McKnight RD, et al. A study to develop clinical decision rules for the use of radiography in acute ankle injuries. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:384–390.