159 Fluid Management

• Shock is defined by inadequate tissue perfusion and not by systemic blood pressure.

• The majority of emergency department patients who require resuscitation are in compensated shock with normal blood pressure.

• Volume expansion with isotonic fluid is the most important immediate therapy for most patients with circulatory insufficiency.

• Resuscitation and maintenance fluids should be tailored to an individual patient’s acid-base and electrolyte status.

• The fluid dose titrated to appropriate end points is more important than the individual fluid class (i.e., crystalloid versus colloid) used for resuscitation.

• Normal vital signs do not guarantee adequate systemic perfusion and should not be the ultimate end point of resuscitation.

• Dynamic measures of fluid responsiveness should be used to assist in the management of patients who remain hypoperfused despite initial empiric volume therapy.

Perspective

Hypovolemia is a common crisis in acute care medicine. Loss of volume is often a direct consequence of acute fluid or blood loss, but relative hypovolemia complicates many clinical conditions. Its severity ranges from mild compensated hypovolemia to shock and hypotension that place end-organ perfusion and function at risk. Fluid therapy to optimize cardiac performance and restore fluid and electrolyte balance is a cornerstone of medical support. Timely and appropriate fluid therapy maintains macrocirculatory and microcirculatory support and reduces mortality.1 In contrast, both underresuscitation and overly aggressive fluid therapy can have an adverse impact on organ function and outcome.2,3 Inadequate resuscitation risks leaving a patient in compensated shock. Overly aggressive fluid administration results in volume overload without improving oxygen delivery and is associated with worse clinical outcomes.4 In addition to sustaining circulating blood volume, intravenous (IV) fluids also correct and maintain normal acid-base and electrolyte balance. A thorough understanding of the appropriate selection, timing, and goals of fluid therapy is vital to optimize patient care.

Pathophysiology

Water

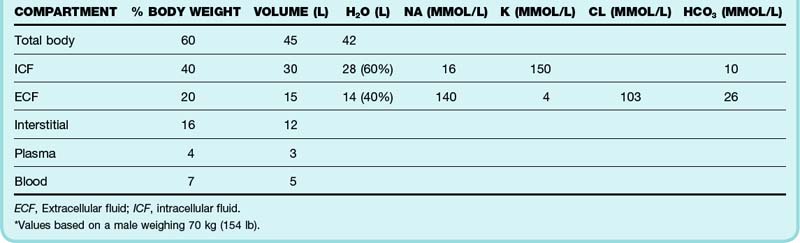

Water is the most abundant constituent of the body. An adult man weighing 70 kg (154 lb) contains approximately 45 L of water, which accounts for 60% of body mass (Table 159.1). Total body water (TBW) is proportional to lean body mass and affects maintenance fluid requirements. TBW is physiologically compartmentalized into intracellular and extracellular spaces. The extracellular compartment is anatomically and conceptually divided into vascular and interstitial spaces.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Absolute hypovolemia occurs as a consequence of loss of water, electrolytes, or blood (or any combination of the three) (Box 159.1). Patients with hypovolemia most often have symptoms related to reduced cardiac output such as fatigue, dyspnea, postural dizziness, and near or true syncope. Tolerance is variable and depends on the acuity and severity of the hypovolemia, associated anemia, individual physiologic reserve, and primary cause. Organ dysfunction is often a heralding sign of hypovolemia and may occur in the absence of global hypoperfusion or frank hemodynamic instability.

Shock is defined as a state of inadequate tissue perfusion in which oxygen delivery does not meet metabolic requirements. The term does not reflect perfusion pressure—shock may occur with low, normal, or elevated blood pressure. Unfortunately, clinical signs are unreliable indicators of oxygen delivery and blood volume.5,6

Compensated shock refers to inadequate perfusion in the setting of normal blood pressure. The majority of critically ill patients are in compensated shock. The difficulty in identifying these patients prompted the terms occult and cryptic shock to describe normotensive patients with alternative evidence of cardiovascular insufficiency. Hyperlactatemia (<3 mmol/L) is an important marker to aid in identification of these high-risk patients.7 Left unresuscitated, these patients often progress to frank hypotension.

Brief episodes of hypotension are important markers of hypoperfusion and herald progressive hemodynamic deterioration. These self-limited episodes of transient hypotension represent progressive exhaustion of cardiovascular compensation and are the first sign of uncompensated shock.8 Uncompensated shock is characterized by hypotension that occurs when physiologic attempts to maintain normal perfusion pressure are overwhelmed or exhausted. Sustained hypotension signifies a late stage of shock.

Volume status and perfusion should be evaluated during every emergency department (ED) examination (Box 159.2). Delayed capillary refill, dry axillae and mucous membranes, abnormal skin turgor, sunken eyes, and a depressed fontanelle are classic but imperfect hallmarks of hypovolemia.9,10 Peripheral cyanosis, cool extremities, and cutaneous mottling (cutis marmorata) characterize classic hypodynamic shock but are not a primary indication of hypovolemia. In contrast, early hyperdynamic septic shock may be manifested as peripheral vasodilation with warm extremities and brisk capillary refill.

Treatment

Early recognition of hypovolemia and shock must be coupled with aggressive resuscitation to have an effect on patients. Timely resuscitation is important because the window to reverse critical organ hypoperfusion and affect clinical outcome is measured in hours and often transpires in the ED.11 Equivalent but delayed resuscitation yields greater morbidity and mortality.12–15 The immediate goal of fluid resuscitation is intravascular expansion to optimize stroke volume and oxygen delivery.

Fluid Resuscitation

Resuscitation Targets (End Points)

The target end point of resuscitation guides the dose and selection of interventions, including fluid therapy. In high-risk patients, fluid selection appears to be less important than volume dosage titrated to an appropriate therapeutic end point.1,16 Rapid restoration of systemic pressure (mean arterial pressure > 65 mm Hg) is a first priority to support vital organ autoregulated blood flow. However, stabilization of blood pressure does not guarantee adequate organ perfusion—resuscitation aimed primarily at normotension risks leaving the patient in persistent compensated shock.17 Unfortunately, there is no single best resuscitation end point for all clinical circumstances. An approach seeking to normalize a combination of both global and regional perfusion markers is most prudent (Box 159.3).

Empiric Fluid Challenge

Total volume requirements are difficult to predict at the onset of resuscitation and are often underestimated. Classic hypovolemia, as occurs with acute hemorrhage or fluid loss, may stabilize rapidly with appropriate volume expansion. The 3 : 1 rule of hemorrhage resuscitation suggests that 3 volumetric units of crystalloid are required to replete an extracellular fluid deficit of 1 unit of blood loss. However, experimental models have confirmed that with severe hemorrhage, volume requirements exceed the 3 : 1 suggestion. Pathologic vasodilation and capillary leak contribute to the need for ongoing volume replacement. Exaggerated transcapillary fluid shifts are common with early burns, peritonitis, and pancreatitis. Crystalloid requirements average greater than 60 mL/kg in the first hours of septic shock but may be as high as 200 mL/kg to normalize perfusion.18,19

Predicting Volume Responsiveness

The utility of fluid administration to improve stroke volume depends on a number of variables, including venous tone and ventricular function. Critically ill patients may manifest continued hypoperfusion despite initial empiric volume resuscitation. As an example, only half of hypotensive patients with sepsis are stabilized with volume resuscitation alone.19 In the absence of overt clinical hypovolemia or ongoing fluid loss, volume responsiveness should not be assumed. Continued fluid therapy does not have any impact on macrocirculatory flow in up to 50% of critically ill patients.20

Volume or preload responsiveness refers to the ability to augment stroke volume with fluid administration. In contrast to an empiric volume challenge, volume responsiveness is gauged before fluid administration, and the resulting information is used to guide whether fluid administration is a solution to reverse clinical hypoperfusion. Fluid loading in volume-unresponsive patients is optimally avoided because it delays appropriate therapy and contributes to fluid excess that contributes to organ dysfunction, including hypoxemic respiratory failure and abdominal compartment syndrome.4 A more rational approach for patients who remain hypoperfused after initial empiric management incorporates selection and titration of subsequent therapy under the guidance of objective cardiovascular monitoring.

A target central venous pressure (CVP) of 8 to 12 mm Hg is recommended to maximize preload before instituting pressor and inotropic support.21 Unfortunately, there is no consistent threshold CVP to reliably estimate response to fluid administration.22 Values that are considered low, normal, or high can be found in patients who respond positively to fluid.20

Dynamic hemodynamic indices are more dependable signs of volume responsiveness. Respirophasic variation in stroke volume during positive pressure mechanical ventilation is among the most useful signs of fluid responsiveness.20 Respiratory collapse of the inferior vena cava (IVC) is another helpful indicator. Minimal IVC variation is associated with supranormal CVP and a low probability of fluid responsiveness. Inspiratory IVC collapse greater than 50% indicates a high probability of augmenting stroke volume with fluid therapy.

Fluid Selection

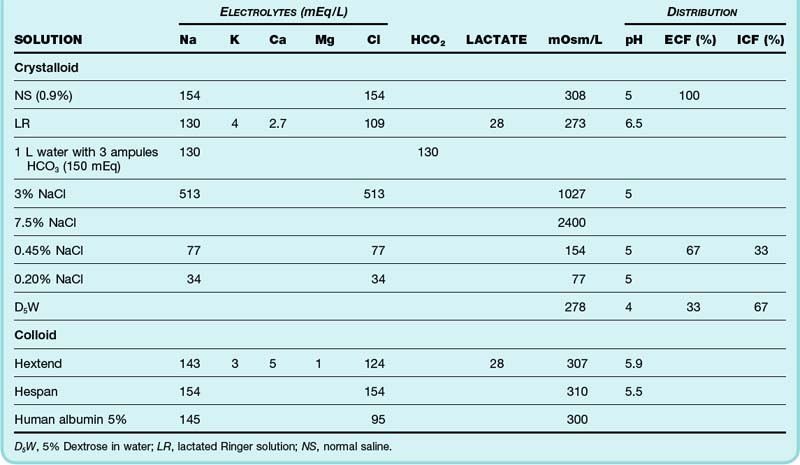

Early resuscitation and ongoing replacement of fluid deficits may be performed with a variety of fluids. Because each possesses specific benefits and potential disadvantages in given clinical scenarios, an understanding of fluid composition is important. Isotonic solutions are effective volume expanders (Table 159.2). Electrolyte disorders (including hypernatremia and hyponatremia) take secondary priority to isotonic volume loading in hypoperfused patients. Hypotonic solutions are ineffective and inappropriate volume expanders.

Colloids

Colloid solutions are composed of electrolyte preparations reinforced with macromolecules designed to preserve colloid oncotic pressure. Vascular retention of colloid makes these formulations more efficient volume expanders with a longer duration of action than is the case with crystalloids. Crystalloid solutions require two to four times more volume for equivalent resuscitation. Dilutional hypoalbuminemia, transcapillary fluid shift, and interstitial and pulmonary edema may therefore be limited with colloid use. When dosed to the same end points, colloids and crystalloids are equally effective. Randomized clinical trials have failed to prove clinical superiority of one fluid class, with comparable rates of mortality and lung dysfunction.23,24 Traumatic brain injury remains one important exception in which isotonic albumin is associated with a higher risk for adverse outcomes when compared with equivalent crystalloid.23,25 Crystalloid solutions remain the standard ED choice for resuscitation and confer a significant cost advantage over colloid solutions.

Human albumin and hydroxyethyl starch (HES) are the colloids primarily used in clinical practice in the United States. Human albumin solutions are heat-sterilized derivatives of donor plasma. Isotonic 5% albumin is recommended for resuscitation of patients with severe hypoalbuminemia and end-stage liver disease, but there is little outcome evidence to support this position.21,26,27 HES, a semisynthetic polymerized amylopectin compound, has supplanted dextran and gelatin-based colloids. A 6% solution provides volume expansion equivalent to that of 5% albumin. The renal dysfunction and coagulopathy that complicated early-generation synthetic colloids do not appear to be clinically significant with new-generation HES solutions.

Hypertonic Solutions

Hyperoncotic Albumin

Infusions of hyperoncotic albumin (20% to 25%) result in vascular expansion greater than two times the volume administered. Besides the obvious benefits of small-volume resuscitation, improved portability, and more rapid hemodynamic stabilization, hyperoncotic albumin has additional advantages. Synergistic interaction with administered drugs and primary antioxidant effects are explanations hypothesized for the improved morbidity linked to hyperoncotic albumin administrated to patients with complicated hypoalbuminemic states.27 End-stage liver disease is one important example in which hyperoncotic albumin attenuates renal dysfunction and death in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis or those undergoing large-volume paracentesis.28–30

Hypertonic Saline

Hypertonic sodium solutions rapidly expand intravascular volume by mobilizing water from the interstitial and intracellular spaces. A small infusion expands plasma several times the volume infused. Used alone, the hemodynamic impact of hypertonic crystalloid is transient. Hypertonic crystalloid is often used in combination with hyperoncotic colloid (6% dextran or 10% HES) to sustain vascular expansion. Animal resuscitation models have demonstrated additional benefits, including enhanced cardiac output, improved microcirculatory flow, and attenuated inflammatory response. Hypertonic saline is safe, but data are insufficient to conclude that it is better than isotonic crystalloid for the resuscitation of patient with burns, trauma, or sepsis.31 Severely traumatized patients with associated traumatic brain injury remain an exceptional use for hypertonic saline, but outcome evidence is mixed.32,33

Special Treatment Considerations

Minimal-Volume Resuscitation of Hemorrhagic Shock

The rationale is that the increased intravascular pressure and hemodilution resulting from aggressive fluid resuscitation compounds the blood loss by precipitating rebleeding from hemostatic sites. Animal models of uncontrolled hemorrhage reveal that aggressive fluid administration reduces oxygen delivery and results in higher mortality. The widely recognized Houston experience showed a mortality benefit in penetrating trauma victims, but the results have yet to be matched by other investigators.34,35 In this strategy, hypotensive patients with a source of uncontrolled life-threatening hemorrhage receive IV fluids titrated to sustain critical organ flow until definitive surgical control is achieved (see Box 159.3). Conventional resuscitation ensues once surgical hemostasis is achieved.

Burn Resuscitation

Patients with partial-thickness and full-thickness burns exhibit marked fluid shifts related to denuded skin, injured tissue, and the systemic inflammatory response. Early anticipation of these large fluid requirements prevents underresuscitation. The Parkland formula remains the most commonly used guide for acute burn resuscitation. Formula calculations are based on the time of injury rather than the time until medical attention and incorporate prehospital fluid administration. All burn formulas provide only estimates of fluid requirements. The requirements must be modified and individualized based on patient response because volume needs may substantially exceed formula approximation.36 LR solution is the resuscitation crystalloid preparation of choice for acute burn management. In addition to burn formula replacement, maintenance fluid requirements should be allocated. Urine output greater than 1 mL/kg/hr is a traditional end point of acute burn resuscitation and may be augmented by the perfusion end points discussed earlier.

Oral Rehydration Therapy

Oral rehydration therapy is a valuable tool for maintenance and correction of mild to moderate dehydration secondary to gastroenteritis in children and adults. It remains underused in the United States despite worldwide success, guideline support, and evidence from controlled trials.37 When used as per published guidelines, oral rehydration therapy is comparable with IV therapy, but with reduced hospitalization and improved safety and expense. Small aliquots of fluid (as low as 5 mL, depending on patient size and tolerance) are administered by bottle, spoon, syringe, or nasogastric tube at regular 2- to 5-minute intervals to meet deficit and maintenance goals. After patient and family education, appropriate fluid selection is the most important factor in successful oral rehydration therapy.

Maintenance Fluid Therapy

Routine water and electrolyte maintenance is based on normal energy expenditure, sensible loss from urine and stool, and insensible loss from the respiratory tract and skin. Calculations assume euvolemia and are adjusted for body mass. The greater per-kilogram fluid requirements in children are proportionate to their TBW and metabolism (Table 159.3).

| BODY WEIGHT | DAILY MAINTENANCE (mL/DAY) | HOURLY MAINTENANCE (mL/HR) |

|---|---|---|

| 1-10 kg | 100 mL/kg | 5 mL/kg |

| 10-20 kg | 1000 mL plus 50 mL/kg | 40mL plus 2 mL/kg |

| 20-80 kg | 1500 mL plus 20 mL/kg† | 60mL plus 1 mL/kg† |

* Note that the following two formulas calculate disparate rates. The difference between these calculated rates is clinically insignificant. Sodium and chloride—2 to 3 mEq per 100 mL water; potassium—1 to 2 mEq per 100 mL water. D5NS with 20 mEq KCl is a common maintenance solution for most euvolemic pediatric patients and provides 20% of the daily calories at a routine maintenance rate. Comorbid conditions or electrolyte abnormalities may require modification.

† To a maximum of 2400 mL/day or 100 mL/hr.

Hypotonic solutions (e.g., 0.45% and 0.2% sodium chloride) with or without dextrose and potassium are popular fixed-combination maintenance solutions. Hospitalized patients often suffer impaired free water excretion because of nonosmotic release of antidiuretic hormone, which makes them vulnerable to hyponatremia. The serum sodium concentration provides a simple and accurate marker of hydration status. Isotonic maintenance solutions should be considered in all patients (including children), especially those with a serum sodium concentration of less than 138 mEq/L.38–40 Glucose infusions are best formulated by adding dextrose to an electrolyte solution (e.g., LR solution, 0.45% or 0.9% normal saline) rather than using 5% dextrose in water, which behaves as electrolyte-free water on sugar metabolism.

1 Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368–1377.

2 Murphy CV, Schramm GE, Doherty JA, et al. The importance of fluid management in acute lung injury secondary to septic shock. Chest. 2009;136:102–109.

3 Balogh Z, McKinley BA, Cocanour CS, et al. Supranormal trauma resuscitation causes more cases of abdominal compartment syndrome. Arch Surg. 2003;138:637–642.

4 Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, et al. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2564–2575.

5 Wo CC, Shoemaker WC, Appel PL, et al. Unreliability of blood pressure and heart rate to evaluate cardiac output in emergency resuscitation and critical illness. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:218–223.

6 Shippy CR, Appel PL, Shoemaker WC. Reliability of clinical monitoring to assess blood volume in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1984;12:107–112.

7 Howell MD, Donnino M, Clardy P, et al. Occult hypoperfusion and mortality in patients with suspected infection. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1892–1899.

8 Jones AE, Aborn LS, Kline JA. Severity of emergency department hypotension predicts adverse hospital outcome. Shock. 2004;22:410–414.

9 McGee S, Abernethy WB, III., Simel DL. The rational clinical examination. Is this patient hypovolemic? JAMA. 1999;281:1022–1029.

10 Steiner MJ, DeWalt DA, Byerley JS. Is this child dehydrated? JAMA. 2004;291:2746–2754.

11 Barbee RW, Reynolds PS, Ward KR. Assessing shock resuscitation strategies by oxygen debt repayment. Shock. 2010;33:113–122.

12 Jones AE, Brown MD, Trzeciak S, et al. The effect of a quantitative resuscitation strategy on mortality in patients with sepsis: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2734–2739.

13 Kern JW, Shoemaker WC. Meta-analysis of hemodynamic optimization in high-risk patients. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1686–1692.

14 Carcillo JA, Davis AL, Zaritsky A. Role of early fluid resuscitation in pediatric septic shock. JAMA. 1991;266:1242–1245.

15 Han YY, Carcillo JA, Dragotta MA, et al. Early reversal of pediatric-neonatal septic shock by community physicians is associated with improved outcome. Pediatrics. 2003;112:793–799.

16 Jansen TC, van Bommel J, Schoonderbeek FJ, et al. Early lactate-guided therapy in intensive care unit patients: a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:752–761.

17 Rady MY, Rivers EP, Nowak RM. Resuscitation of the critically ill in the ED: responses of blood pressure, heart rate, shock index, central venous oxygen saturation, and lactate. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:218–225.

18 Brierley J, Carcillo JA, Choong K, et al. Clinical practice parameters for hemodynamic support of pediatric and neonatal septic shock: 2007 update from the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:666–688.

19 Hollenberg SM, Ahrens TS, Annane D, et al. Practice parameters for hemodynamic support of sepsis in adult patients: 2004 update. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1928–1948.

20 Michard F, Teboul JL. Predicting fluid responsiveness in ICU patients: a critical analysis of the evidence. Chest. 2002;121:2000–2008.

21 Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:296–327.

22 Osman D, Ridel C, Ray P, et al. Cardiac filling pressures are not appropriate to predict hemodynamic response to volume challenge. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:64–68.

23 Finfer S, Bellomo R, Boyce N, et al. A comparison of albumin and saline for fluid resuscitation in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2247–2256.

24 Perel P, Roberts I. Colloids versus crystalloids for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2007. CD000567

25 Myburgh J, Cooper DJ, Finfer S, et al. Saline or albumin for fluid resuscitation in patients with traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:874–884.

26 Vincent JL, Navickis RJ, Wilkes MM. Morbidity in hospitalized patients receiving human albumin: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2029–2038.

27 Dubois MJ, Orellana-Jimenez C, Melot C, et al. Albumin administration improves organ function in critically ill hypoalbuminemic patients: a prospective, randomized, controlled, pilot study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2536–2540.

28 Sort P, Navasa M, Arroyo V, et al. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:403–409.

29 Runyon BA. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2004;39:841–856.

30 Jacob M, Chappell D, Conzen P, et al. Small-volume resuscitation with hyperoncotic albumin: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Crit Care. 2008;12(2):R34.

31 Bunn F, Roberts I, Tasker R, et al. Hypertonic versus near isotonic crystalloid for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2004. CD002045

32 Bulger EM, May S, Brasel KJ, et al. Out-of-hospital hypertonic resuscitation following severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1455–1464.

33 Simma B, Burger R, Falk M, et al. A prospective, randomized, and controlled study of fluid management in children with severe head injury: lactated Ringer’s solution versus hypertonic saline. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1265–1270.

34 Bickell WH, Wall MJ, Jr., Pepe PE, et al. Immediate versus delayed fluid resuscitation for hypotensive patients with penetrating torso injuries. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1105–1109.

35 Dutton RP, Mackenzie CF, Scalea TM. Hypotensive resuscitation during active hemorrhage: impact on in-hospital mortality. J Trauma. 2002;52:1141–1146.

36 Blumetti J, Hunt JL, Arnoldo BD, et al. The Parkland formula under fire: is the criticism justified? J Burn Care Res. 2008;29:180–186.

37 Fonseca BK, Holdgate A, Craig JC. Enteral vs intravenous rehydration therapy for children with gastroenteritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:483–490.

38 Choong K, Kho ME, Menon K, et al. Hypotonic versus isotonic saline in hospitalised children: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:828–835.

39 Hoorn EJ, Geary D, Robb M, et al. Acute hyponatremia related to intravenous fluid administration in hospitalized children: an observational study. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1279–1284.

40 Moritz ML, Ayus JC. Water water everywhere: standardizing postoperative fluid therapy with 0.9% normal saline. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:293–295.