120 First Trimester Ultrasonography

• Patients with ectopic pregnancy have highly variable and often unhelpful findings on physical examination.

• Ultrasound is the initial imaging modality of choice to locate a pregnancy in the first trimester.

• Emergency physicians proficient in ultrasound are capable of rapidly diagnosing ectopic pregnancy and expediting definitive care.

• Most first trimester pregnancies can be localized within the uterus on initial ultrasound in the emergency department.

• All patients discharged from the emergency department without a confirmed intrauterine pregnancy by ultrasound should thoroughly understand the “ectopic precautions,” have close outpatient follow-up arranged with their obstetrician, and have the means to return immediately to the emergency department if complications arise.

Introduction

All female patients of reproductive age seen in the emergency department (ED) with vaginal bleeding or abdominal or back pain should have a urine or serum pregnancy test performed. Ectopic pregnancy is the number one cause of death in patients in the first trimester.1 Emergency physicians (EPs) caring for these patients understand that no historical clues or physical findings can effectively affirm or refute an ectopic pregnancy.2 The rate-limiting step is finding the location of the pregnancy. Ultrasound imaging and interpretation play a crucial role in this decision-making process. The faster this information is available, the quicker management can be implemented. In the late 1980s, a few EP pioneers invested the time and effort to learn the technical and interpretive skills necessary to bring ultrasound to the bedside.3 The ability to locate a first trimester pregnancy saves valuable time in the search for an ectopic pregnancy.4 Ultrasound performed at the patient’s bedside quickly classifies patients by ultrasound criteria.5 Based on this ultrasound classification, management strategies can be implemented. The following sections describe the ultrasound techniques and management skills used in symptomatic patients in the first trimester of pregnancy.

Evidence-Based Review

In most EDs, when “formal” ultrasound is traditionally ordered, it is actually performed in the department of radiology. This requires (1) time to transport the patient out of the ED, (2) a sonographer available to obtain the images, and (3) a radiologist to interpret the study. Ultimately, the combination of these factors postpones the diagnosis, delays definitive care, and increase the patient’s length of stay.4 As an alternative to formal ultrasound, many EPs have learned how to perform and interpret ultrasound images at the patient’s bedside. As early as 1989, a number of small studies suggested that EPs were able to perform ultrasound for ectopic pregnancies with high sensitivity.3 When previous studies from multiple institutions are compiled to increase the sample size (N = 2057), it is estimated that EPs have a pooled sensitivity of 99.3% when diagnosing ectopic pregnancies at the bedside. Sensitivity is defined as the proportion of bedside ultrasound images demonstrating a true absence of definitive intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) in patients with ectopic pregnancies.4

Multiple retrospective and prospective studies from the late 1990s and early 2000s have reported that when compared with formal imaging, the use of bedside ultrasound to evaluate first trimester bleeding reduced length of stay in the ED by a mean time of 48 to 169 minutes. Time of day, day of the week, and whether ultrasound technicians were in house 24 hours a day were some of the factors that had an impact on the length of stay.5 Finally, based on two separate studies from the early 2000s, bedside ultrasound performed by EPs saved an estimated $229 to $1244 per ED visit when compared with patients who underwent radiology-performed ultrasound. In some cases this was a 40% savings in billed charges.5 Literature from the past 20 years has and continues to demonstrate that ultrasound performed by an EP to evaluate for ectopic pregnancies is feasible, fast, and accurate. Bedside ultrasound in symptomatic first trimester pregnant patients has high sensitivity in ruling out ectopic pregnancy, speeds time to diagnosis, and decreases true costs.

How to Scan

Transabdominal Technique

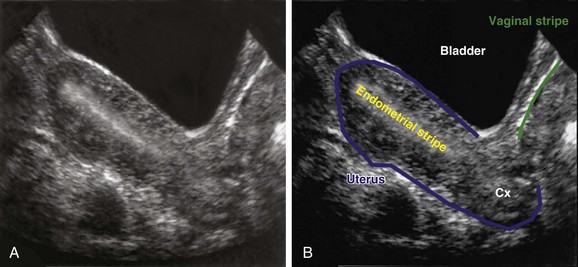

In the sagittal view, in which the uterus is seen in its long axis, the probe is placed just superior to the pubic symphysis with the indicator pointed toward the patient’s head. The anterior-most organ on screen is the fluid-filled, triangular-shaped bladder. Just posterior to the bladder is the pear-shaped uterus. The uterus more commonly lies in an anteverted position, with the fundus pointed toward the anterior abdominal wall, but it may also be seen in a retroverted lie with the fundus pointing posteriorly toward the spine. The endometrial stripe serves as the landmark for identifying the longitudinal uterus in the midline. The endometrial stripe is a result of the endometrial mucosal lining coming together to form a hyperechoic, curvilinear line that continues as the cervical stripe more inferiorly (Fig. 120.1, A and B). After the midline of the longitudinal uterus is identified, the probe is panned from side to side to evaluate the entire width of the uterus. Much of the hyperechoic area surrounding the uterus is the bowel and rectum, which are poorly defined because of their solid and gas contents.

Endovaginal Technique

The arrival of endovaginal transducers in the 1980s significantly improved the quality of ultrasound imaging in female patients. Simplified, the engineering design placed an ultrasound transducer on the end of a stick that could be inserted into the vaginal vault. This permits the transducer scanning head to be in close proximity to the pelvic organs, which has several important implications in ultrasound imaging. First, there is a clearer path to transmit and receive echoes, and second, the shorter distance between the transducer and the pelvic organs allows higher transducer frequencies to be used.6 In contrast to the transabdominal approach, the quality of images from an endovaginal approach is enhanced with an empty bladder because of less distortion of the pelvic anatomy.

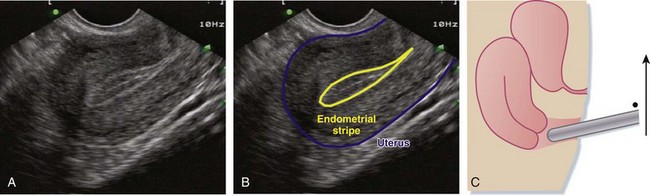

For the sagittal view, the transducer is inserted so that the indicator is straight up and down, with the body sliced into left and right halves. Even after voiding, the bladder usually retains a small amount of fluid, which enables this anechoic structure to be used as a landmark in endovaginal imaging. After initially placing the probe into the vaginal vault, the bladder or uterus (or both) may not initially be visible. To look for these structures, the handle of the probe should be brought down and the footprint of the probe tilted more anteriorly and angled up to get the uterus in its full, longitudinal (sagittal) plane. In this plane, the anterior-most structure is a sliver of bladder, the pear-shaped uterus is posterior to the bladder, and the more hyperechoic bowel and rectum surround the uterus (Fig. 120.2, A to C). As in transabdominal imaging, the endometrial stripe serves as the landmark for identifying the longitudinal uterus in its midline. Once it is identified, the uterus should be interrogated along its entire width by fanning from side to side.

Identification and Localization of the Pregnancy

First trimester pregnancies can be categorized into three groups according to location: intrauterine, extrauterine, or indeterminate (Box 120.1). Within these three categories, further subdivisions into one of five diagnostic possibilities based on specific criteria (Box 120.2) are possible. The significance of this unambiguous classification scheme is that it corresponds with EP management strategies for first trimester symptomatic patients.

Intrauterine Pregnancy

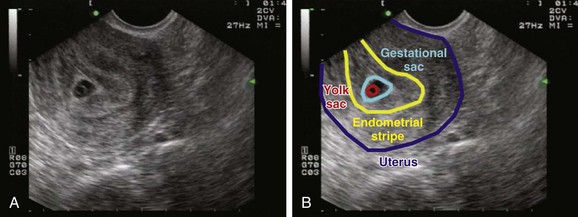

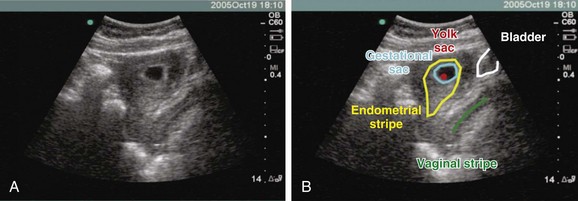

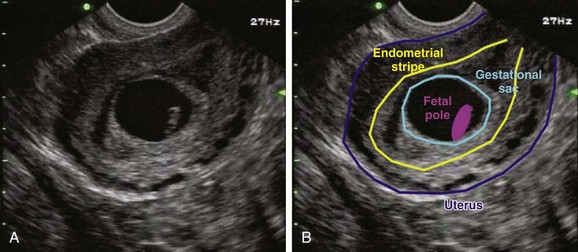

To define a pregnancy as intrauterine, it is imperative to have a clear understanding of the criteria necessary to support the diagnosis by ultrasound (Box 120.3). The first component of the criteria is to visualize a gestational sac with a mean sac diameter (height, width, and length) larger than 5 mm and an echogenic ring. Second, this gestational sac must be clearly visualized within the endometrial lining of the uterus and many times may demonstrate a “double decidual sac sign.” Finally, this gestational sac, which lies within the endometrial echo of the uterus, must contain a yolk sac or a fetal pole. Although this may be excessive for a radiologist who uses the double decidual sac sign as the earliest criteria for an IUP, it is a conservative safety measure that has served EPs well to avoid confusing the pseudogestational sac of an ectopic pregnancy with a true IUP. Because ectopic pregnancies secrete hormones that stimulate the endometrial lining, occasionally there may be changes in the endometrial lining that can approximate the appearance of a gestational sac. This pseudosac will never have an inner yolk sac or fetal pole. Use of these two additional findings for defining an IUP helps ensure that the EP will not be confused. Whether scanning from a transabdominal or an endovaginal approach, all these criteria should be visualized and documented on every sonogram. The safest way to ensure that these criteria are present is a systematic approach to documenting these landmarks. In the endovaginal approach, documentation is best achieved by obtaining a single sagittal view of the gestational and yolk sacs clearly within the endometrial echo of the uterus, along with the inferiorly positioned endometrial stripe as it passes through the corpus and cervical region of the uterus (Fig. 120.3, A and B). In the transabdominal approach, documentation is best achieved by obtaining a single sagittal view of the gestational and yolk sacs clearly within the endometrial echo of the uterus, along with the anteriorly positioned bladder and the inferiorly positioned vaginal stripe (Fig. 120.4, A and B). By identifying pregnancies as intrauterine, ectopic pregnancy has effectively been excluded with reasonable certainty. There is a theoretic risk for a heterotopic pregnancy of approximately 1 in 30,000 pregnancies.7 When assisted reproduction is involved, the heterotopic rate is 1 in 7000 overall and as high as 1 in 900 with induction of ovulation.8 Even when a live IUP is identified in an assisted reproduction patient, close follow-up with the fertility specialist is recommended.

Box 120.3 Diagnostic Criteria

Intrauterine pregnancy—Gestational sac with a concentric echogenic ring lying within the endometrial echo of the uterus that is greater than 5 mm in mean sac diameter (height, width, and length) and contains a yolk sac with or without a fetal pole

Live intrauterine pregnancy—Gestational sac with a concentric echogenic ring lying within the endometrial echo of the uterus that is greater than 5 mm in mean sac diameter (height, width, and length) and contains a yolk sac plus a fetal pole and cardiac activity

Abnormal intrauterine pregnancy—Gestational sac with a concentric echogenic ring lying within the endometrial echo of the uterus that is greater than 13 mm in mean sac diameter (height, width, and length) without a yolk sac or greater than 18 mm in mean sac diameter (height, width, and length) without a fetal pole or with an obvious fetal pole without cardiac activity

No definitive pregnancy—No definite gestational sac is apparent within the endometrial echo of the uterus, or if a gestational sac is visualized, it is less than 5 mm in mean sac diameter (height, width, and length)

Extrauterine gestation: ectopic—Gestational sac with a concentric echogenic ring lying outside the endometrial echo of the uterus that is greater than 5 mm in mean sac diameter (height, width, and length) and contains a yolk sac with or without a fetal pole and cardiac activity

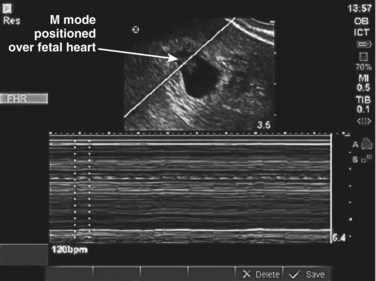

Live Intrauterine Pregnancy

Once the pregnancy is determined to be intrauterine, the next designation is viability. This involves real-time documentation of the cardiac activity normally present at 6 weeks’ gestational age when using the endovaginal technique and at 7 to 8 weeks’ gestation when using the transabdominal technique. The criteria for documentation of a live IUP is detailed below (see Box 120.3). Simply having a fetal pole within the endometrial echo of the uterus will not suffice (Fig. 120.5, A and B). For our purposes, an IUP is not live until cardiac activity is documented. The flickering of cardiac activity is an unmistakable sign of life that can be identified by the novice sonographer and the patient as well. Documentation can be confirmed by video in B mode or by identifying the fetal heart rate by M mode (Fig. 120.6). Pulsed wave Doppler should never be used to document fetal heart rates because of the theoretic risk to the fetus of the increased heat generated by this form of ultrasound. Novice sonographers will occasionally use the zoom feature and record or print an image of a pregnancy without any definite landmarks confirming the pregnancy as intrauterine (Fig. 120.7). The problem is that ectopic pregnancies can be indistinguishable with this particular example of a cone-down view, which does not allow visualization of the landmarks that support the criteria for an IUP.

Abnormal Intrauterine Pregnancy

A pregnancy can be categorized as abnormal when the gestational sac is disproportionate to its contents. For example, by the time that a gestational sac measures 13 mm in diameter, a yolk sac should clearly be visualized. Likewise, by 18 mm, all intrauterine gestational sacs containing live embryos should have cardiac activity. When using conservative criteria, it is safe to conclude that any sac larger than 13 mm without a yolk sac or larger than 18 mm without evidence of cardiac activity is termed abnormal (Fig. 120.8, A and B). It has been shown in the obstetric ultrasound literature that gestational sacs reaching 13 mm in size with no yolk sac or fetal pole have virtually no viability and ultimately result in miscarriage. In most cases in which viability is equivocal, there is no rush to make a specific diagnosis (IUP versus abnormal IUP). Because these pregnancies have only a gestational sac visualized on ultrasound, obstetric consultation and close follow-up in 48 hours, repeated ultrasound, and quantitative measurement of β-human chorionic gonadotropin will be required.

Extrauterine Pregnancy

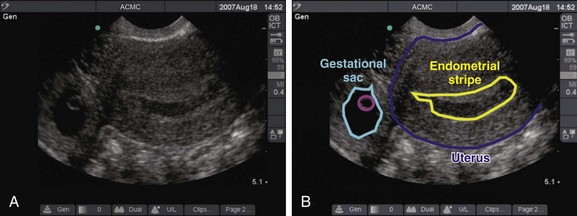

Ectopic pregnancies represent approximately 2% of reported pregnancies, and ectopic pregnancy–related deaths account for 9% of all pregnancy-related deaths.9 The most common implantation site is within the fallopian tube (95.5%). Sites of tubal implantation in descending order of frequency are ampullary (73.3%), isthmus (12.5%), fimbrial (11.6%), and interstitial (2.6%). The remaining sites are ovarian (3.2%) and abdominal (1.3%).10 Visualization of an ectopic pregnancy on ultrasound, even for experienced sonographers, is frequently difficult. As opposed to an IUP, for which ultrasound confirms the diagnosis, an extrauterine pregnancy is often not substantiated by ultrasound and is just presumed because of the absence of an IUP or other findings of a normal pregnancy. The criteria for diagnosis of an extrauterine gestation is a gestational sac outside the endometrial echo of the uterus with evidence of a yolk sac or fetal pole (Fig. 120.9, A and B). In patients who do not have this definitive finding, the diagnosis can be made either intraoperatively or by serial ultrasound in patients who are being monitored very closely. A “ruptured” ectopic pregnancy is frequently suspected on clinical grounds. Supportive sonographic findings of an intraperitoneal fluid collection or an adnexal mass (or both) further strengthen this suspicion.11 Recent literature suggests that a transabdominal approach in which a large intraperitoneal fluid collection is revealed will decrease the time to diagnosis and treatment.14 A pregnant female with free fluid visualized in the right upper quadrant should have these findings communicated immediately to obstetric consultants to help facilitate a shorter time to the operating room.

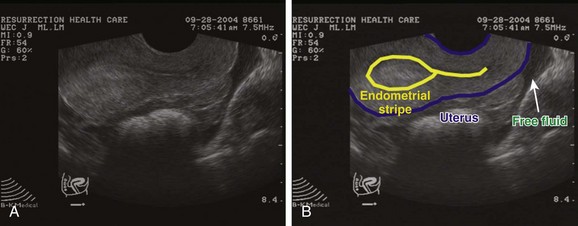

No Definitive Pregnancy

The diagnosis of no definitive pregnancy is established when a technically adept emergency ultrasound examination fails to diagnose an intrauterine or extrauterine gestation (Fig. 120.10, A and B). When this is encountered, three possible diagnoses exist. First, it is possible that an early IUP is present but no definitive signs are visualized within the uterus by ultrasound. Second, the products of conception my have been aborted and the empty uterus is a result of a miscarriage. Finally, a concealed ectopic pregnancy is not identified by emergency ultrasound.

Absence of proof is not proof of absence. It should be borne in mind that patients in whom no definitive pregnancy is diagnosed are at high risk for an ectopic pregnancy. The presence of free fluid in the pouch of Douglas or elsewhere in the pelvis should increase suspicion for an ectopic pregnancy substantially. The literature varies widely in defining ectopic pregnancy rates in patients with indeterminate or no definitive pregnancy. This may be due to variation in the specific criteria used to define this category. Many researchers have added subgroups such as probable ectopic pregnancy and probable IUP.11,12 The take-home message is that all patients in whom no definitive IUP is diagnosed should be managed closely with our obstetric colleagues regardless of the β-human chorionic gonadotropin level. An interdepartmental policy addressing this issue would clearly be advantageous to each specialty and the patient.

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pregnancy-related mortality ratios—United States, 1991-1999. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 2003;52(2):1–8.

2 Abbott J, Emmans LS, Lowenstein SR. Ectopic pregnancy: ten common pitfalls in diagnosis. Am J Emerg Med. 1990;8:515–522.

3 Jehle D, Davis E, Evans T, et al. Emergency department sonography by emergency physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7:605–611.

4 Blaivas M, Sierzenski P, Plecque D, et al. Do emergency physicians save time when locating a live intrauterine pregnancy with bedside ultrasonography? Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:988–993.

5 Mateer J, Valley VT, Aiman EJ, et al. Outcome analysis of a protocol including bedside endovaginal sonography in patients at risk for ectopic pregnancy. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27:283–289.

6 Burke RK, Fine RA. Basic physical principle of ultrasonography for the practicing clinician. Infertil Reprod Med Clin North Am. 1991;2:643.

7 Lyons EA, Levi CS, Sidney M, Rumak, CM, Wilson SR, Charboneau WK. Dashefsky in diagnostic ultrasound, 2nd ed, vol. 2. St. Louis: Mosby, 1998;999.

8 Glassner MJ, Aron E, Eskin BA. Ovulation induction with clomiphene and the rise in heterotopic pregnancies: a report of two cases. J Reprod Med. 1990;35:175–178.

9 NCHS. Advanced report of final mortality statistics, 1992. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, CDC; 1994. (Monthly Vital Statistics Report; vol 43, no. 6, suppl).

10 Bouyer J, Coste J, Fernandez H, et al. Sites of ectopic pregnancy: a 10-year population-based study of 1800 cases. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3224–3230.

11 Dart R, Kaplan B, Ortiz L. Normal intrauterine pregnancy is unlikely in emergency department patients with either menstrual days >38 days or β-hCG >3,000 mIU/mL, but without a gestational sac on ultrasonography. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:967–971.

12 Moore C, Tod WM, O’Brien E, Lin H. Free fluid in Morison’s pouch on bedside ultrasound predicts need for operative intervention in suspected ectopic pregnancy. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;8:755–759.

13 Barnhart KT, Fay CA, Suescum M, et al. Clinical factors affecting the accuracy of ultrasound in symptomatic first trimester pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:299–306.