15

Figurate Erythemas

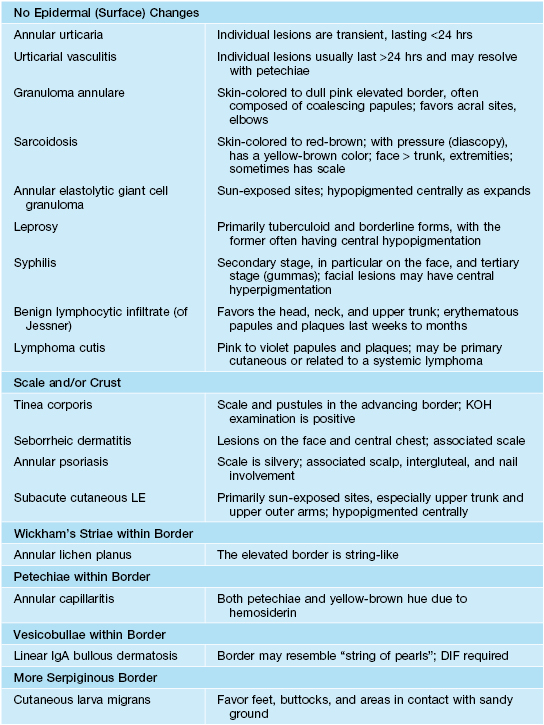

A number of cutaneous diseases can have an annular, arciform, or polycyclic configuration, from urticaria to granuloma annulare and tinea corporis (Table 15.1). Sites of involvement, rate of expansion, and characteristics of the border assist in narrowing the differential diagnosis, along with histologic examination of the active edge. This chapter discusses in more detail the classic figurate erythemas.

Table 15.1

Additional entities that can have an annular, arciform, or polycyclic configuration.

These disorders are covered in other chapters. See text for discussion of the classic figurate erythemas. Both erythema multiforme and erythema migrans can have a bull’s-eye appearance.

DIF, direct immunofluorescence; KOH, potassium hydroxide; LE, lupus erythematosus.

Erythema Annulare Centrifugum (EAC)

• This gyrate erythema is sometimes divided into superficial and deep forms, based on clinicopathologic findings, with the superficial form being minimally elevated with “trailing” white scale (Fig. 15.1A) and the deep form having a more infiltrated border (Fig. 15.1B); some authors reserve the designation EAC for the superficial form.

Fig. 15.1 Erythema annulare centrifugum. A Superficial form, with polycyclic plaques and delicate scale on the inner margin of the advancing edge (trailing scale). The scale is detached centrally. B Deep form, with obvious elevation of advancing edges and without trailing scale.

• DDx: Tinea corporis (especially if scale is present); if no surface changes, annular urticaria (Fig. 15.2), benign lymphocytic infiltrate (of Jessner), cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia, cutaneous lupus erythematosus (tumidus), and lymphoma cutis as well as the other entities covered in this chapter and Table 15.1; in some patients, the diagnosis of EAC is rendered after exclusion of other disorders.

Erythema Marginatum

• Migratory annular and polycyclic erythematous eruption that represents a major Jones criterion (Fig. 15.3); subcutaneous nodules can also develop, but during a later phase of the disease; both findings are seen in the minority of patients.

Fig. 15.3 Erythema marginatum (rheumaticum). Polycyclic and evanescent annular lesions are seen on the trunk of this young patient. Courtesy, Agustin España, MD.

• Associated systemic manifestations: carditis, migratory polyarthritis, chorea, fever.

Erythema Gyratum Repens

• Migratory figurate erythema composed of multiple concentric rings that is said to resemble the grain of wood (Fig. 15.4); the lesions can migrate up to 1 cm per day and may have associated scale or pruritus.

Fig. 15.4 Erythema gyratum repens. Multiple concentric annular plaques, with a wood-grain appearance. Courtesy, Agustin Alomar, MD.

• Paraneoplastic dermatosis in the vast majority of patients, with lung cancer and breast cancer representing the most common underlying malignancies; patients may have other paraneoplastic phenomena, e.g. acquired ichthyosis, palmoplantar keratoderma.

Erythema Migrans (EM; Erythema Chronicum Migrans [ECM])

• Can be localized to the site of the bite of an infected Ixodes tick (Fig. 15.5) or as the disease progresses, become disseminated with multiple secondary lesions (Fig. 15.6); several species of Ixodes can transmit disease, including I. scapularis, I. pacificus, I. ricinus.

Fig. 15.6 Disseminated erythema migrans. Multiple circular and a few annular plaques are scattered on the lower extremities as well as the trunk (not shown). Courtesy, Thomas Schwarz, MD.

• At the site of the tick bite, usually after a period of 1 or 2 weeks (range 2–28 days), an erythematous patch or plaque appears that expands over days to weeks to reach a diameter of at least 5 cm; central clearing can result in an annular lesion and sometimes the lesion has a bull’s-eye appearance; occasionally, vesicles are seen.

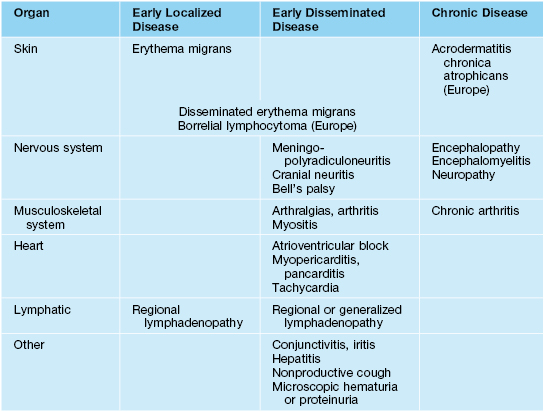

• Transmission usually requires attachment of the infected Ixodes tick for over 24 hours; if untreated, sequelae include arthritis, Bell’s palsy, and atrioventricular heart block (Table 15.2); Ixodes ticks may also transmit babesiosis and human anaplasmosis.

Table 15.2

Stages and major organ manifestations of Lyme borreliosis.

Adapted from Müllegger RR. Dermatological manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2004;14:296–309.

• Development of additional cutaneous findings (e.g. pseudolymphoma, acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans; Fig. 15.7) is seen in individuals infected outside the United States and reflects the geographic distribution of different genospecies of Borrelia, e.g. B. afzelii is found in Europe but not the United States.

Fig. 15.7 Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans is another manifestation of Lyme borreliosis. Note the shiny and wrinkled skin plus more visible superficial veins – signs of atrophy.

• DDx: exaggerated local reaction to an arthropod bite, cellulitis, allergic contact dermatitis, southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI), nonpigmented fixed drug eruption, and other causes of pseudocellulitis (see Table 61.2); of note, peak specific IgM antibodies usually appear at 3–6 weeks into infection so they may not be detected in patients with early EM (false-negative rate as high as 60%).

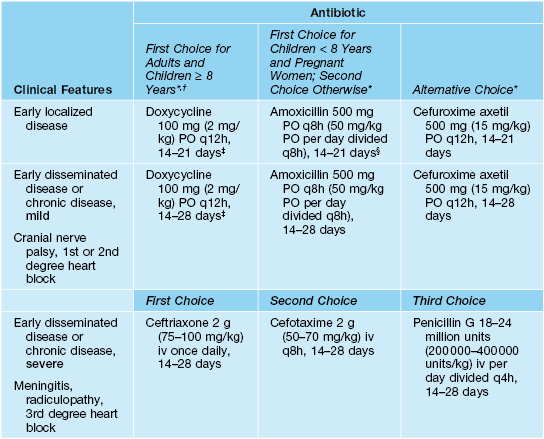

• Rx is outlined in Table 15.3; for patients who (1) live in an endemic area, (2) had a tick attached for >36 hours, (3) removed the tick within the past 72 hours, and (4) had the tick identified as I. scapularis, a single dose of oral doxycycline (200 mg) may reduce the risk of developing Lyme borreliosis from 3.2% to 0.4%.

Table 15.3

Treatment options for borreliosis.

Doses for children are in parentheses, with adult dose as maximum. A Jarisch–Herxheimer-like reaction with an increase in systemic symptoms and in the size or intensity of the inflammation of the erythema migrans lesion occurs in ~15% of patients within 24 hours after the initiation of antimicrobial therapy.

* No comparative trials for early localized disease, so no established superior treatment; doxycycline also treats human anaplasmosis.

† Avoid doxycycline in children <8 years and pregnant women.

‡ In a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial, similar outcomes were observed for a 10-day versus 20-day course of doxycycline.

§ Recommended for 21 days for pregnant women.

For further information see Ch. 19. From Dermatology, Third Edition.