Fever in the Adult Patient

Perspective

Fever is a common presenting complaint in both pediatric and adult (aged 18-65 years) emergency department (ED) patients. Patients often confuse fever with a disease process itself, rather than a sign of an illness. Morbidity and mortality rates from febrile illnesses vary dramatically with age. Younger adults with fever usually have benign self-limited disease, with less than 1% mortality. The challenge in this group is to identify the rare meningitis or septic conditions when confronted with a predominance of self-limited viral and focal bacterial diseases. Patients older than 65 years, or those with chronic disease who have fever, represent a group at high risk for serious disease. Morbidity and mortality rates in this group are significant. From 70 to 90% are hospitalized, and 7 to 9% die within 1 month of admission.1 Infection is the most common cause of fever in these patients, and most of these infections are bacterial in nature. Three body systems—the respiratory tract, the urinary tract, and the skin and soft tissue—are the target for more than 80% of these infections.1,2 The relative mortality and morbidity for any given infection are much higher in the geriatric population. For example, elders are at 5 to 10 times greater risk for urinary tract infections and 15 to 20 times for appendicitis.1,3 Even viral illnesses that are generally not fatal, such as influenza, can be highly lethal in elder persons.

Pathophysiology

Moderate elevations of the body temperature may serve to aid the host defense by increasing chemotaxis, decreasing microbial replication, and improving lymphocyte function. Elevated temperatures directly inhibit the growth of certain bacteria and viruses.4

Fever also results in certain increased physiologic costs to the host, including increased oxygen consumption, metabolic demands, protein breakdown, and gluconeogenesis. These costs are particularly problematic in elders, who typically have a smaller margin of reserve for any given body system. It is well established that the ability to develop fever in elders is somewhat impaired. Older individuals also are known to have lower baseline temperatures than younger adults.5 It has not been shown that treatment of fever with antipyretics has a beneficial effect on outcome or prevents complications; however, treatment to reduce the fever makes febrile patients more comfortable.4

Diagnostic Approach

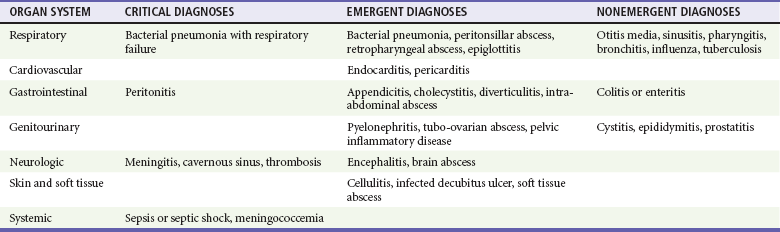

The complete differential diagnosis for the patient in the ED with fever is extensive. The major infectious and noninfectious causes are summarized in Table 12-1 and Box 12-1, respectively. The vast majority of serious causes are infectious in origin. Immediate threats to life are from decompensated shock (usually septic), respiratory failure (related to shock or pneumonia), or central nervous system infection (meningitis). Some critical noninfectious causes of fever also exist (see Box 12-1), but these are relatively rare and frequently do not occur with fever as the primary symptom.

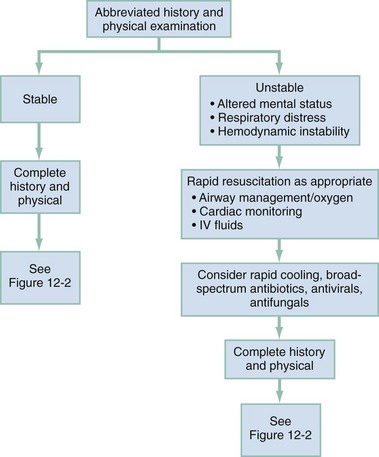

A primary medical decision in acute febrile illness is based on assessment of patient stability (Fig. 12-1). Patients with life-threatening signs and symptoms, including significant alterations in mental status, respiratory distress, and cardiovascular instability, may require rapid, vigorous treatment. Prompt airway management and initiation of monitoring, intravenous access, fluid resuscitation, supplemental oxygen, and respiratory support are often necessary despite incomplete information concerning the cause of the fever. Sustained temperatures above 41.0° C are rare but can be damaging to neural tissue and require rapid cooling (e.g., misting, fans, cooling blankets).

In the younger, otherwise healthy patient with fever, immediate threats to life such as toxic or septic shock, meningitis, meningococcemia, and peritonitis should be considered and treated empirically. In older, chronically ill patients with fever, most of the serious illnesses originate from infections in the respiratory tract, the genitourinary tract, and the skin and soft tissues.2 Meningitis, although less common, can also be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in this group.

Pivotal Findings

Although the differential diagnosis of fever is broad, most of the treatable causes are of infectious origin. Most of these causes of fever may be diagnosed by careful history and physical examination alone.6 Age and the presence of underlying medical conditions can substantially influence the evaluation and subsequent decision-making regarding management.

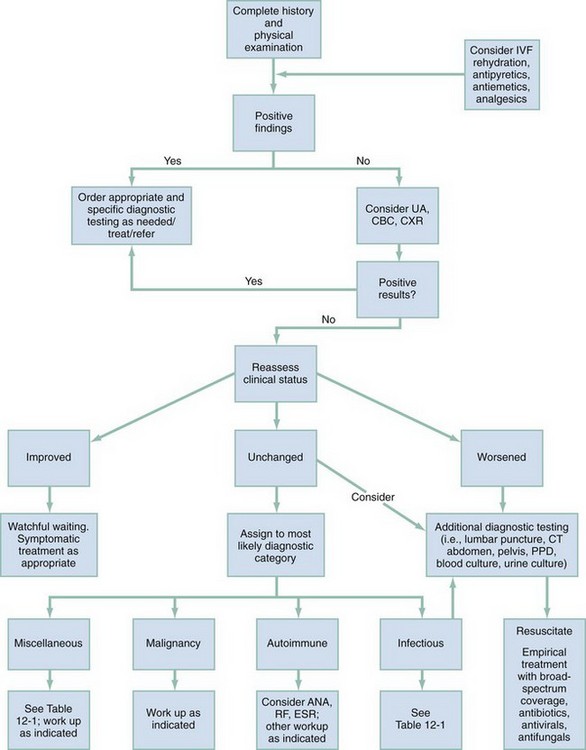

An approach to diagnosis and management of the healthy, otherwise well, stable adult patient with acute febrile illness is shown in Figure 12-2. In younger and otherwise healthy adults, self-limited, localized bacterial infections or benign systemic viral infections are usually the cause of fever. The challenge with this group is to identify the rare life-threatening illness, such as meningococcemia, meningitis, or systemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection.

In the older or chronically ill population, fever is frequently a sign of severe illness. Usually the cause is infectious. In addition to the most common infectious causes of illness (respiratory, urinary, or skin sources), infections such as meningitis, cholecystitis, appendicitis, and diverticulitis are considered and may cause atypical signs and symptoms in elders or immunosuppressed patients. In these populations, subtle changes in behavior may be the only sign of severe infection. Abnormal vital signs, especially significant tachypnea and hypotension, may portend a complicated and severe course. Seventy-five percent of the cases of functional decline in nursing home patients are a result of infection.1,2

Symptoms

The onset of the fever, its duration and magnitude, and any associated symptoms help identify possible causes and severity of illness. Localizing symptoms such as dysuria or productive cough are especially helpful. The timing of the fever and its patterns may implicate certain diseases (e.g., malaria). Recent or remote travel, chronic illnesses, past surgeries, hospitalizations, and treatment modalities may raise the suspicion of exotic or nosocomial infections. The presence of prosthetic heart valves or any indwelling device may be critical to the diagnosis. With the emergence of community-acquired MRSA, it is important to seek a history of skin infections in close family members or other close contacts. MRSA should also be considered in military personnel, prisoners, and persons involved in competitive sports that involve close contact.7,8

Atypical symptoms of illness are common in elder patients. Pneumonia or urinary tract infection in the older patient may be heralded by only a change in mental status, difficulty ambulating, or some other functional decline. Dysuria, frequency, and flank pain often are absent entirely in elders with urinary tract infection. Patients with pneumonia may inconsistently demonstrate productive cough or shortness of breath. Other frequent but nonspecific symptoms include anorexia, weight loss, weakness, lethargy, nausea, and recurrent falls.1,2 A history of cancer with recent chemotherapy or radiation therapy may be a clue to leukopenia or other immunodepressed states. Assessment of the patient’s baseline mental and physical function often relies on the reports of others who know the patient well.

Signs

Although the most accurate measure of core body temperature is thought to be via the thermistor of a pulmonary artery catheter, in the ED, rectal temperature measurements or, when a Foley catheter is indicated, bladder thermistors are the most practical and accurate.9 Axillary and tympanic temperatures often are unreliable. Oral temperatures may be transiently distorted by recent ingestion of hot or cold liquids, smoking, or hyperventilation. For example, rectal temperatures are typically 0.7 to 1.0° C higher than oral temperatures.9

The skin and extremities should be evaluated for rash, petechiae, joint inflammation, or evidence of soft tissue infection. In the absence of trauma, tenderness over the long bones or the spine may be evidence of osteomyelitis or neoplastic processes. Elders and bedridden patients should be checked for the presence of pressure sores or decubitus ulcers.2

Ancillary Testing

Ancillary testing is directed by the history and physical examination. The two most useful ancillary tests, especially in elder patients, are urinalysis and chest radiography. Chest radiographs are often helpful in the diagnosis of pulmonary infection but may be difficult to interpret in the patient with concurrent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, dehydration, or other chronic lung disease. The urinalysis, although not foolproof, is highly accurate for urinary tract infection, especially in men. Although the white blood cell count is almost universally used in the evaluation of febrile patients, it lacks the sensitivity and specificity to be of discriminatory value. The white blood cell count may incorrectly indicate serious infection when none is present or may be normal in the presence of life-threatening infection.10 Other indirect tests of infection and inflammation, such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, are also plagued with irregular sensitivity and poor specificity. Gram’s stain of appropriate specimens may be helpful, and cultures may be ordered, although the results do not often influence emergency evaluation and treatment. With the emergence of MRSA, it has become increasingly important to obtain cultures from soft tissue skin abscesses in patients considered at risk for MRSA infection. In elder or chronically ill patients with acute fever of unknown source, blood and urine cultures are frequently appropriate. Outpatient blood cultures should rarely, if ever, be done. A patient ill enough to require blood cultures from the ED generally requires hospitalization and empirical antibiotic coverage. Cerebrospinal fluid evaluation should be considered when mental status changes are evident, or if headache, meningismus, or other unexplained neurologic symptoms are present and cannot be clearly accounted for by infection outside the central nervous system. Thyroid function studies may be helpful when thyroid storm is suspected. Arterial or venous blood gas studies may help identify patients with critical disease who require prompt treatment.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of infectious causes of fever are summarized in Table 12-1. The differential diagnoses of noninfectious causes of fever are listed in Box 12-1. However, differences in patient characteristics can cause different manifestations of the same illness. For example, pneumonia or a urinary tract infection manifests in and is tolerated by an 80-year-old very differently compared with a young adult. A careful history and physical examination, along with strategic ancillary testing, will allow the practitioner to identify when a critical condition is present and will determine the operational tempo of subsequent evaluation and treatment.

Empirical Management

Patients with temperatures greater than 41.0° C require prompt and vigorous treatment with antipyretics and possibly external cooling measures. Temperatures above this range can result in damage to neuronal tissue. There is no evidence for improved outcome by routine use of antipyretic therapy, such as acetaminophen, in patients without extreme temperature elevation, but it is not harmful, and patients often feel better when their temperature declines.4 Recent studies have shown that intravenous acetaminophen is as effective as oral acetaminophen and may be used in patients who are unable to take oral medication.11

References

1. Angus, DA, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: Analysis of the incidence, outcome and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2011;29:1303–1310.

2. High, KP, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation of fever and infection in older adults residents of long term care facilities: 2008 update by the Infectious Disease Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:149–171.

3. Tal, S, Guller, V, Gurevich, A, Levi, S. Fever of unknown origin in the elderly. J Intern Med. 2002;252:295–304.

4. Greisman, LA, Mackowiak, PA. Fever: Beneficial and detrimental effects of antipyretics. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2002;15:241–245.

5. Roghhmann, MC, Warner, J, Mackowiak, PA. The relationship between age and fever magnitude. Am J Med Sci. 2001;322:68–70.

6. Tolan, RW, Jr. Fever of unknown origin: A diagnostic approach to this vexing problem. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2010;49:207–210.

7. Aiello, AE, Lowy, FD, Wright, LN, Larson, EL. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among U.S. prisoners and military personnel: Review and recommendations for future studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:335–341.

8. Turbeville, SD, Cowan, LD, Greenfield, RA. Infectious disease outbreaks in competitive sports: A review of the literature. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1860–1865.

9. O’Grady, N, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation of new fever in critically ill adult patients: 2008 update from the American College of Critical Care Medicine and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1330–1353.

10. Furer, V, Raveh, D, Picard, E, Goldberg, S, Izbicki, G. Absence of leukocytosis in bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia. Prim Care Respir J. 2011;20:276–281.

11. Peacock, WF, Breitmeyer, JB, Pan, C, Smith, WB, Royal, MA. A randomized study of the efficacy and safety of intravenous acetaminophen compared to oral acetaminophen for the treatment of fever. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:360–366.