3

Fever and Rash

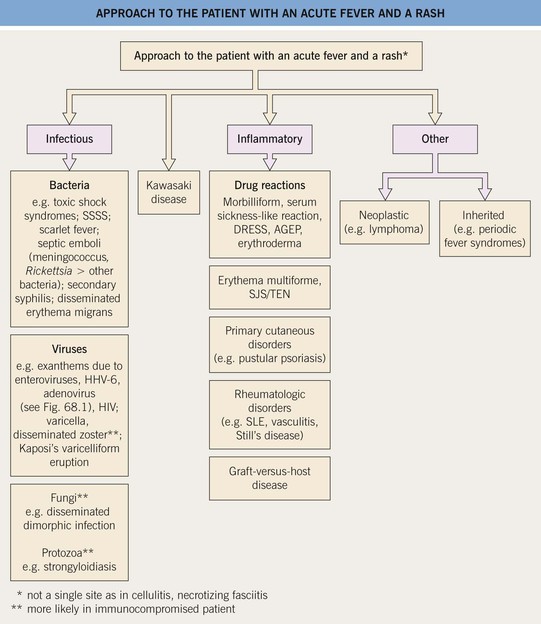

• A variety of infectious and inflammatory conditions can present with fever and a rash (Fig. 3.1). The cutaneous findings range from a morbilliform eruption or urticaria (Figs. 3.2 and 3.3) to confluent erythema (Fig. 3.4) to petechial, vesiculobullous, and pustular lesions (Figs. 3.5–3.9).

Fig. 3.1 Approach to the patient with an acute fever and a rash. AGEP, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (also referred to as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome [DIHS]); HHV, human herpes virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SSSS, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Fig. 3.2 Morbilliform drug eruptions. A Fine pink macules and thin papules, becoming confluent on the posterior upper arm, which is a dependent area in this hospitalized patient. B More edematous (‘urticarial’) pink papules; unlike true urticaria, these lesions are not transient. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 3.3 Urticaria and serum sickness-like reaction. A Giant annular urticaria (urticaria ‘multiforme’) in a young child with a recent viral upper respiratory tract infection. Individual lesions last <24 hours, but they often resolve with a dusky purplish hue that can lead to misdiagnosis as erythema multiforme. B Serum sickness-like reaction due to amoxicillin. Some of the urticarial papules and annular plaques have a purpuric component, and the eruption was accompanied by high fevers, lymphadenopathy, arthralgias, and acral edema. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 3.4 Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Diffuse, tender erythema, with an early superficial erosion in the antecubital fossa. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 3.5 Viral exanthems. A Enteroviral exanthem presenting as widespread small pink papules, many with petechiae centrally. B, C Widespread vesicular eruption due to coxsackievirus A6 infection. D Scattered vesicles on erythematous bases in varicella, with lesions in different stages of evolution. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 3.6 Stevens–Johnson syndrome. The patient initially developed multiple small pink papules mimicking a morbilliform eruption, but with accentuation on the palms (A). A day later, confluent erythema and bullae had developed (B), and involvement of the vermilion lips and conjunctiva was evident. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 3.7 Bullous pemphigoid. Multiple tense bullae and crusted erosions on a background of erythematous skin. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 3.8 Pustular psoriasis in a pediatric patient. Multiple sterile papulopustules and expanding annular red plaques with pustulation at the advancing edge. This eruption was widespread and associated with fever and malaise. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 3.9 Staphylococcal folliculitis on the back of a hospitalized boy. Other eruptions with a predilection for occluded sites such as the back of a bedridden patient include miliaria rubra (especially if febrile), non-infectious folliculitis, Grover’s disease (in the setting of chronic photodamage), and candidiasis. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

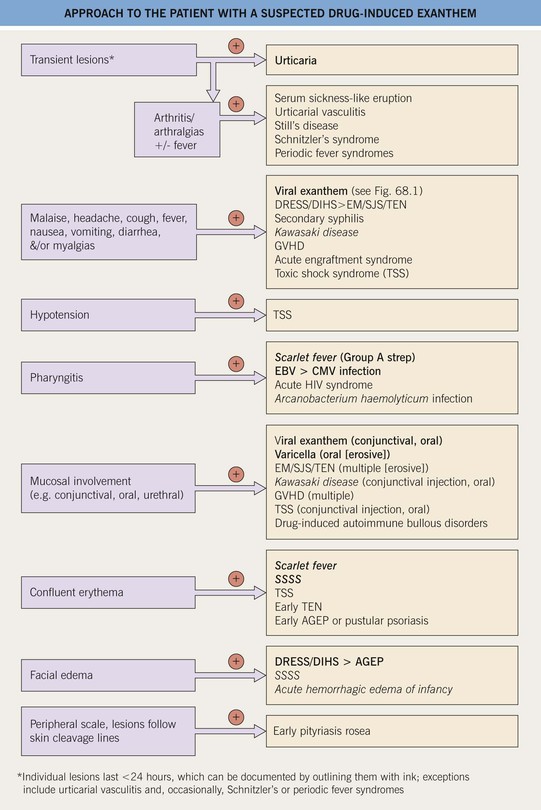

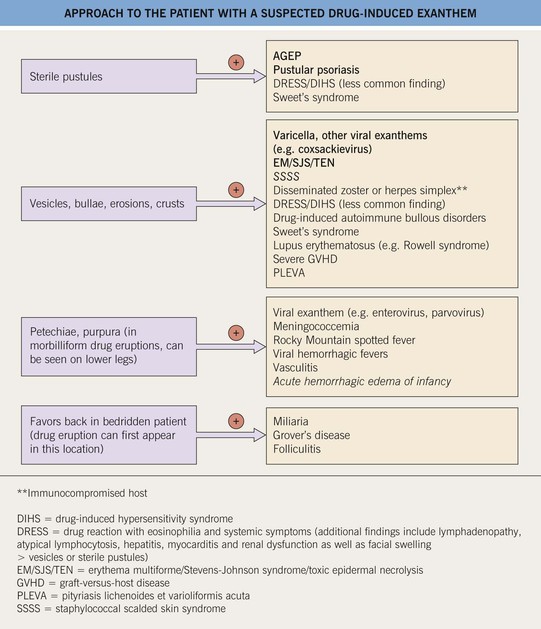

• Clinical features that differentiate among entities in the differential diagnosis of an exanthematous drug eruption are summarized in Fig. 3.10.

Fig. 3.10 Approach to the patient with a suspected drug-induced exanthem (morbilliform, urticarial). With a few exceptions (e.g., pityriasis rosea, drug-induced autoimmune bullous disorders), patients with these entities may be febrile. Entities in italics occur primarily in children. Toxic shock syndrome can be staphylococcal or streptococcal (see Ch. 61). Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is also referred to as a pustular drug eruption. Drug-induced autoimmune bullous disorders: bullous pemphigoid or linear IgA bullous dermatosis > drug-induced pemphigus.

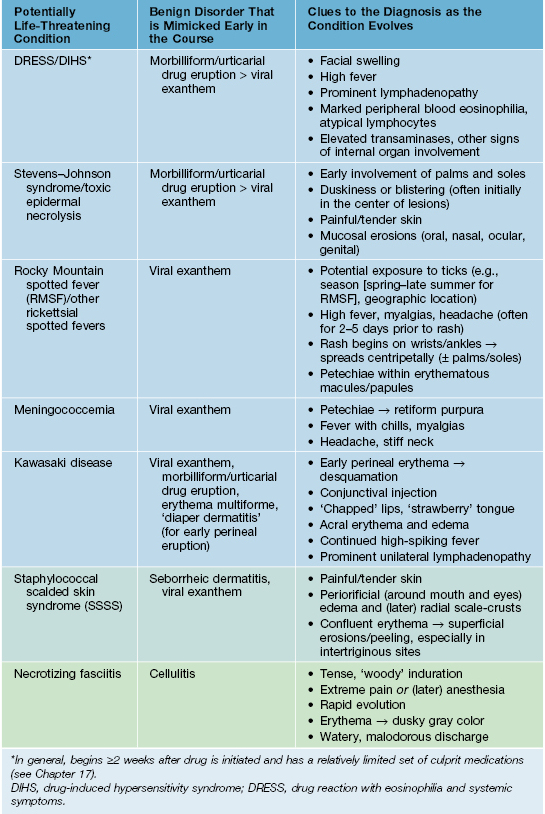

• Although the initial skin findings of some potentially life-threatening disorders can mimic a more common benign disorder, the development of other cutaneous and extracutaneous features as the condition evolves points to the correct diagnosis (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1

Potentially life-threatening conditions with initial skin findings that can mimic a more common benign disorder.

The cutaneous manifestations are most likely to resemble those of milder disorder during the first 24 hours. Diffuse erythema, often beginning on the trunk, or a scarlatiniform exanthem can also be early manifestations of toxic shock syndrome.

Kawasaki Disease

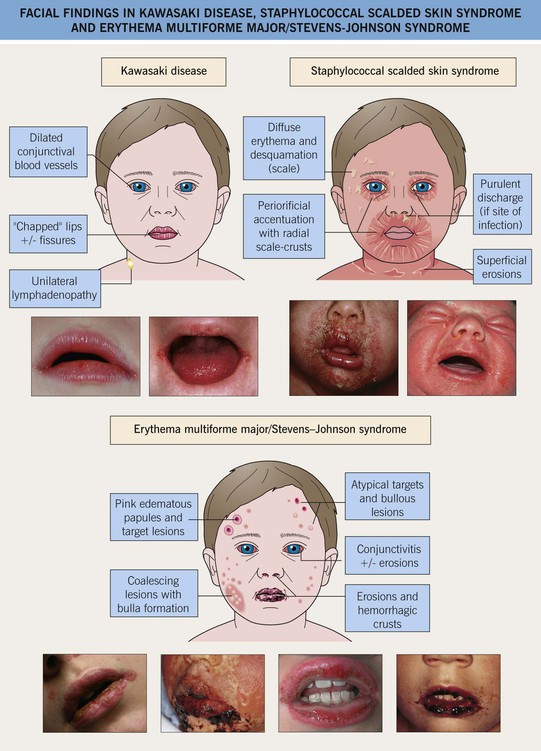

• Diagnostic criteria include fever (>39°C/102°F) for ≥5 days plus the presence of ≥4 of the following five criteria.

– Bilateral nonpurulent bulbar conjunctival injection.

– Oropharyngeal changes such as ‘chapped’/fissured lips (Fig. 3.11), a ‘strawberry’ tongue, and diffuse hyperemia.

Fig. 3.11 Facial findings in Kawasaki disease, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and erythema multiforme major/Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Hemorrhagic crusting and erosions of the vermilion portion of the lips can also be seen in primary gingivostomatitis due to herpes simplex virus, pemphigus vulgaris, and paraneoplastic pemphigus.

– Cervical lymphadenopathy (>1.5 cm; usually unilateral).

– Erythema, edema, and (eventually) desquamation of the hands and feet (Fig. 3.12A).

Fig. 3.12 Kawasaki disease. A Erythema and edema of the palm early in the disease course. B, C Erythema multiforme-like lesions becoming confluent in the perineal region on the second day of fever (B), followed by desquamation 2 days later (C). D Erythema (less evident due to the patient’s darkly pigmented skin) and desquamation in the genital area. Involvement of the skin in this location is a characteristic early finding in Kawasaki disease. A–C, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD. D, Courtesy, Anthony Mancini, MD.

– Polymorphous exanthem – morbilliform or urticarial > erythema multiforme-like (Fig. 3.12B), scarlatiniform, or pustular.

• Initial manifestation is often erythema in the perineal area, followed by desquamation (Fig. 3.12B–3.12D).

Periodic Fever Syndromes

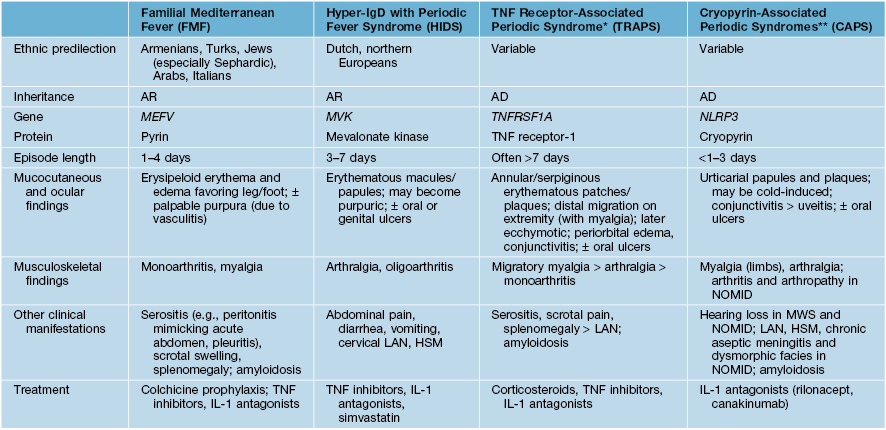

• Group of hereditary autoinflammatory disorders that feature recurrent episodes of fever and rash (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2

Hereditary periodic fever syndromes that present with a rash.

In all of these disorders, episodic ‘attacks’ are characterized by fever and may be associated with headache.

* Includes familial Hibernian fever.

** Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) include familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome, Muckle–Wells syndrome (MWS), and neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID; also known as chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous and articular syndrome [CINCA]).

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; HSM, hepatosplenomegaly; IL-1, interleukin-1; LAN, lymphadenopathy; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

For further information see Chs. 20, 21, 45 and 81. From Dermatology, Third Edition.