Fetal Growth and Development

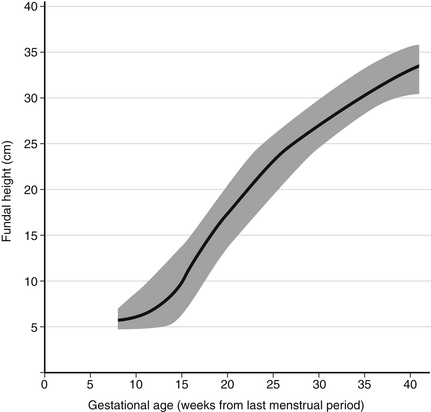

Fetal growth assessments can be made clinically by assessing the fundal height; clinical assessment of fetal weight can be made by performing Leopold maneuvers ( Fig. 2-1).

Leopold maneuvers involve the palpation of the fetus through the maternal abdomen. Advantages of Leopold maneuvers include the fact that the procedure is relatively easy to perform and does not incur the expense of ultrasound; disadvantages include a low sensitivity for macrosomia. In general, clinical estimates of fetal weight are more likely to underestimate the weight of macrosomic infants than to overestimate the weight.

When fetal growth is estimated, several individual biometric parameters are commonly entered into a standard formula to calculate a composite weight. Because two-dimensional estimates of fetal weight do not account for variation in fetal body composition and because of the margin of error inherent in sonographic measurement of fetal biometries, sonographic assessments of fetal weight are associated with a significant (~10% to 20%) margin of error. ∗†

Macrosomia is a term used to describe excessive fetal growth. No threshold weight has been universally accepted, but common definitions include a birth weight above 4000 or 4500 grams. In contrast to macrosomia, which is determined solely by birth weight, the term large for gestational age is used to describe any fetus with an estimated weight above the 90th percentile for a given gestational age. ∗

4. Is there a difference between growth retardation and growth restriction? Define fetal growth restriction.

Symmetric IUGR is characterized by equal reduction in head, abdominal, and skeletal dimensions. It is indicative of an insult during the period of most active cell division, as seen in chromosomal or congenital abnormalities.

Symmetric IUGR is characterized by equal reduction in head, abdominal, and skeletal dimensions. It is indicative of an insult during the period of most active cell division, as seen in chromosomal or congenital abnormalities.

Asymmetric IUGR is distinguished by a reduction in abdominal circumference but sparing of head and skeletal growth. It most likely represents an insult during cell growth caused by extrinsic factors such as uteroplacental insufficiency or maternal vascular disease. ∗

Asymmetric IUGR is distinguished by a reduction in abdominal circumference but sparing of head and skeletal growth. It most likely represents an insult during cell growth caused by extrinsic factors such as uteroplacental insufficiency or maternal vascular disease. ∗

5. How do you differentiate a growth-restricted infant from a small-for-gestational-age (SGA) infant and a low-birth-weight (LBW) infant?

Factors that affect fetal growth are typically categorized as fetal, placental, or maternal in origin and are summarized in Table 2-1. Common examples include the following:

TABLE 2-1

RISK FACTORS FOR INTRAUTERINE GROWTH RESTRICTION

| MATERNAL | PLACENTAL | FETAL |

| Poor or inadequate nutritional intake | Mosaicism | Chromosomal abnormalities |

| Medical disease | Abnormal implantation | Trisomy 13, 18, and 21 |

| Preeclampsia | Previa | Turner syndrome |

| Chronic hypertension | Accreta | Genetic syndromes |

| Collagen vascular disease | Abnormal morphology | Russell–Silver |

| Diabetes mellitus with vascular disease | Small size | Cornelia de Lange |

| Thrombophilia (congenital or acquired) | Bilobed, battledore, or circumvallate | Congenital malformations |

| Asthma | Velamentous cord insertion | Anencephaly |

| Cyanotic heart disease | Lesions | Congenital heart defect |

| Genetic disorder | Chorioangiomata | Congenital diaphragmatic hernia |

| Environment | Abruptio placentae | Gastroschisis |

| High altitude | Infarction | Omphalocele |

| Emotional or physical stress | Secondary to maternal chronic disease | Renal abnormalities |

| Medications and drugs | Chronic abruption | Multiple malformations |

| Warfarin | Infection | Multiple gestation |

| Anticonvulsants | Chorionitis | Twin-twin transfusion syndrome |

| Retin-A | Chorioamnionitis | Infection |

| Cigarette smoking | Funisitis | TORCH infections: Toxoplasmosis, other (syphilis and other viruses), rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus |

| Alcohol | ||

| Cocaine | ||

| Heroin | ||

| Prior obstetric complications | ||

| Spontaneous abortion | ||

| Stillbirth | ||

| Intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight, or premature offspring |

Prior maternal history of fetal growth restriction

Prior maternal history of fetal growth restriction

Maternal history of immunologic or collagen vascular disease

Maternal history of immunologic or collagen vascular disease

Maternal TORCH infection: Toxoplasmosis, Other (syphilis and other viruses), Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, and Herpes simplex virus

Maternal TORCH infection: Toxoplasmosis, Other (syphilis and other viruses), Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, and Herpes simplex virus

Maternal hypertension or preeclampsia

Maternal hypertension or preeclampsia

Genetic abnormalities in the fetus, including some aneuploidies and genetic syndromes

Genetic abnormalities in the fetus, including some aneuploidies and genetic syndromes

Teratogens: cigarette smoke, Retin-A, warfarin, alcohol

Teratogens: cigarette smoke, Retin-A, warfarin, alcohol

7. What is the initial work-up when fetal growth restriction is suspected?

In pregnancies at risk for IUGR, Doppler analysis is used to evaluate placental resistance and fetal status and may improve fetal and neonatal outcomes. Normal umbilical arterial Doppler flow is reassuring and rarely associated with significant morbidity. Absence of end-diastolic flow in the umbilical artery is indicative of significant placental resistance; reversal of flow is suggestive of worsening fetal status and impending demise. Abnormalities in venous circulation (e.g., ductus venosus a-wave reversal) represent worsening circulatory compromise and may reflect a greater risk of fetal death than abnormalities in the arterial circulation. ∗†‡§

Once IUGR is suspected, fetal well-being should be closely monitored with serial antenatal testing (biophysical profile ± non-stress test; Doppler studies); the frequency of testing will be influenced by the gestational age as well as the maternal and the fetal condition. The timing of delivery is based on fetal maturity, signs of fetal distress, or worsening maternal disease. ∗†‡§

The timing of delivery is determined by the gestational age and clinical status of the fetus. For an IUGR fetus at term or near term, delivery is indicated if fetal lung maturity has been documented, there has been minimal fetal growth observed over serial ultrasounds, significant fetal compromise is evident on testing or Doppler study, or maternal status is worsening (e.g., hypertension). The IUGR fetus is at increased risk of metabolic acidosis and hypoxia, which may be apparent in the fetal heart tracing; continuous monitoring is indicated in labor. ∗†‡

An IUGR infant is initially at risk for perinatal asphyxia, intraventricular hemorrhage, meconium aspiration, respiratory distress syndrome, impaired thermoregulation, fasting and alimented hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, hyperviscosity–polycythemia syndrome, immunodeficiency, and necrotizing enterocolitis. The potential long-term complications are cerebral palsy, behavioral and learning problems, and altered postnatal growth. ∗

16. When in gestation do the five senses develop in the fetus?

Touch: Between 8 and 15 weeks of gestation, the fetal somatosensory system develops in a cephalocaudal pattern. By 32 weeks of gestation, the fetus consistently responds to temperature, pressure, and pain.

Touch: Between 8 and 15 weeks of gestation, the fetal somatosensory system develops in a cephalocaudal pattern. By 32 weeks of gestation, the fetus consistently responds to temperature, pressure, and pain.

Taste: Taste buds are morphologically mature by 13 weeks of gestation. By 24 weeks of gestation, gustatory responses may be present.

Taste: Taste buds are morphologically mature by 13 weeks of gestation. By 24 weeks of gestation, gustatory responses may be present.

Hearing: Auditory function begins at 20 weeks of gestation, when the cochlea becomes functional. By 25 weeks of gestation, response to intense vibroacoustic stimuli can be elicited. Sensitivity and frequency resolution approach adult level by 30 weeks of gestation and are indistinguishable from the adult by term.

Hearing: Auditory function begins at 20 weeks of gestation, when the cochlea becomes functional. By 25 weeks of gestation, response to intense vibroacoustic stimuli can be elicited. Sensitivity and frequency resolution approach adult level by 30 weeks of gestation and are indistinguishable from the adult by term.

Sight: Pupillary response to light appears as early as 29 weeks of gestation and is present consistently by 32 weeks of gestation.

Sight: Pupillary response to light appears as early as 29 weeks of gestation and is present consistently by 32 weeks of gestation.

Smell: By 28 to 32 weeks of gestation, premature infants appear to respond to concentrated odor. ∗†

Smell: By 28 to 32 weeks of gestation, premature infants appear to respond to concentrated odor. ∗†

Fetal breathing movements (one or more episodes of rhythmic fetal breathing movement of 30 seconds or more within 30 minutes)

Fetal breathing movements (one or more episodes of rhythmic fetal breathing movement of 30 seconds or more within 30 minutes)

Gross body movements (three or more discrete body or limb movements within 30 minutes)

Gross body movements (three or more discrete body or limb movements within 30 minutes)

Fetal tone (one or more episodes of extension of a fetal extremity with return to flexion, or opening or closing of a hand)

Fetal tone (one or more episodes of extension of a fetal extremity with return to flexion, or opening or closing of a hand)

Qualitative amniotic fluid volume (a single pocket of amniotic fluid exceeding 2 cm)

Qualitative amniotic fluid volume (a single pocket of amniotic fluid exceeding 2 cm)

The presence of a normal assessment is scored as 2 points, and the absence of the finding is scored as 0. The maximum score is 10, and the minimum score is 0. If all of the ultrasound measurements are normal (i.e., BPP = 8), fetal heart monitoring may be omitted because it will not improve the test’s predictive accuracy. If oligohydramnios is detected, further fetal evaluation is necessary, regardless of the BPP. ∗

A regular pattern of fetal breathing movements is observed by 20 to 21 weeks of gestation. Fetal breathing movement is controlled by centers on the ventral surface of the fourth ventricle. As a result, the presence of fetal breathing indicates an intact central nervous system. Fetal breathing movements appear to assist the movement of fetal lung fluid into the amniotic cavity and also tone the respiratory muscles for the initiation of breathing at the time of birth. ∗

19. How does one differentiate pathologic absence of fetal breathing movements from periodic breathing that occurs during fetal sleep?

Fetal sleep cycles are generally approximately 20 minutes in length. Accordingly, to account for the possibility of fetal sleep during an observation period, a BPP must be performed over a minimum of 30 minutes before absence of fetal breathing can be diagnosed. ∗

Whereas the other BPP parameters reflect more acute changes, amniotic fluid volume assessment is a measure of chronic fetal status. Oligohydramnios may be seen in response to impaired uteroplacental perfusion. ∗

Figure 2-2 reveals the relationship between the fetal BPP and mean umbilical venous pH. ∗

Figure 2-2 Relationship between the fetal biophysical profile and mean umbilical venous pH. (From Manning FA, Snijders R, Harman CR, et al. Fetal biophysical profile score. VI: Correlation with antepartum umbilical venous fetal pH. Am J Obstet Gynecol 169:755–763, 1993, as adapted in Spitzer AR: Intensive Care of the Fetus and Neonate. Philadelphia, Elsevier, 2005, p 117.)

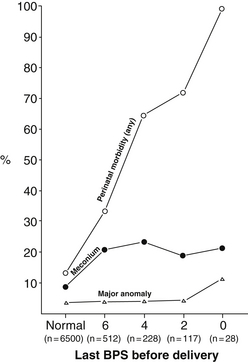

Figure 2-3 depicts the relationship between the fetal BPP and risk of any perinatal morbidity, meconium aspiration, and major congenital anomaly. A normal BPP is never associated with fetal acidemia. The perinatal mortality rate is 0.8 per 1000 live births after a normal BPP. However, a BPP of 0 is almost always associated with fetal compromise.

Figure 2-3 Relationship between the fetal biophysical profile score (BPS) and neonatal outcome. (From Manning FA, Harman CR, Morrison I, et al. Fetal assessment based on fetal biophysical profile scoring. VI: An analysis of perinatal morbidity and mortality. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;162:703–709, as adapted in Spitzer AR: Intensive Care of the Fetus and Neonate. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. p 118.)

2D ultrasound is the primary tool used to screen for fetal structural abnormalities. Although the majority of anomalies are detected in the second or third trimester, some major birth defects can be diagnosed already in the first trimester. Measurement of the nuchal translucency between 11 and 14 weeks of gestation can be used as an early screening tool for aneuploidy, fetal congenital heart disease, and other structural anomalies. ∗

Although many birth defects can be diagnosed prenatally, some major and many minor anomalies are not detected until birth (or later). Several factors can affect the ability to detect a fetal malformation prenatally. In general, major anomalies are generally more likely to be detected before birth than minor abnormalities, but some major anomalies—such as congenital heart disease and orofacial clefts—have relatively low detection rates despite routine prenatal screening. In addition to the nature of the ultrasound facility and the experience of the sonographer or sonologist, ultrasound detection rates can also be affected by maternal factors, such as obesity and abdominal wall scarring, which can make it difficult to see fetal structures prenatally. Furthermore, some anomalies cannot be detected early in gestation either because the structure is not developed at the time the ultrasound is performed or because the abnormality may develop after the scan was done. ∗

27. Aside from two-dimensional ultrasound, what other imaging tools can be used to diagnose anomalies prenatally?

Fetal echocardiogram is recommended in all cases of suspected fetal congenital heart disease as well as in women at increased risk of fetal cardiac anomalies (e.g., personal or family history of congenital heart disease, pregestational diabetes, conception by way of in vitro fertilization, presence of other fetal structural anomalies). ∗†

TTTS is defined as the presence of oligohydramnios in one amniotic sac and polyhydramnios in the other sac in a monochorionic diamniotic twin gestation. TTTS results from an unbalanced interfetal transfusion from a net unidirectional flow through arteriovenous anastomoses deep within the shared placenta. The severity of clinical presentation is modulated by the degree of bidirectional flow from superficial anastomoses. ∗

Complications specific to the recipient twin are polycythemia, systemic hypertension, biventricular cardiac hypertrophy, and congestive heart failure. The donor twin is at risk for growth failure, anemia, high-output cardiac failure, and hydrops. Both twins are at increased risk of congenital anomalies, in utero demise, and cerebral palsy. ∗

Stage I: Oligo-polyhydramnios sequence and visible donor-twin bladder

Stage I: Oligo-polyhydramnios sequence and visible donor-twin bladder

Stage II: “Stuck twin” phenomenon and empty (nonvisible) donor-twin bladder

Stage II: “Stuck twin” phenomenon and empty (nonvisible) donor-twin bladder

Stage III: Critically abnormal Doppler studies in either twin

Stage III: Critically abnormal Doppler studies in either twin

31. What are the available treatment modalities for TTTS?

Serial amnioreduction of the recipient twin amniotic sac increases perfusion to the “stuck twin” by decreasing pressure on the donor amniotic sac.

Serial amnioreduction of the recipient twin amniotic sac increases perfusion to the “stuck twin” by decreasing pressure on the donor amniotic sac.

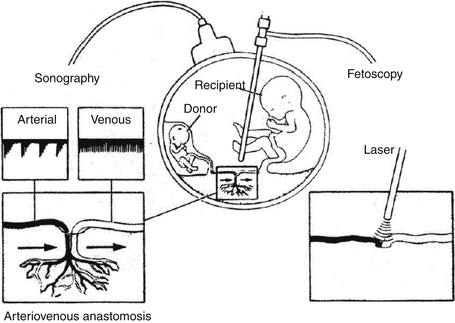

Selective laser photocoagulation of connecting arteriovenous anastomoses decreases the intertwin transfusion ( Fig. 2-4). This is the only intervention that may be potentially curative.

Selective laser photocoagulation of connecting arteriovenous anastomoses decreases the intertwin transfusion ( Fig. 2-4). This is the only intervention that may be potentially curative.

Figure 2-4 Selective laser photocoagulation of connecting arteriovenous anastomoses. (From Cortes RA, Farmer DL. Recent advances in fetal surgery. Semin Perinatol 2004;28:199–211. [with permission])

Amniotic intertwin septostomy restores normal amniotic fluid pressure gradient by allowing hydrostatic flow of amniotic fluid from the recipient to the donor.

Amniotic intertwin septostomy restores normal amniotic fluid pressure gradient by allowing hydrostatic flow of amniotic fluid from the recipient to the donor.

Selective feticide by cord occlusion is reserved for severe or refractory cases and imminent in utero fetal demise of one twin to improve the survival of the co-twin. ∗

Selective feticide by cord occlusion is reserved for severe or refractory cases and imminent in utero fetal demise of one twin to improve the survival of the co-twin. ∗

32. What pathophysiologic factors prompt treatment for fetal tachyarrhythmias? What are the possible fetal interventions?

The major concern in fetuses with tachyarrhythmia (e.g., supraventricular tachycardia and atrial flutter) is compromised cardiac output leading to the development of fetal hydrops. When cardiac output is compromised, maternal antiarrhythmic therapy may be initiated. If the fetal arrhythmia remains refractory, direct fetal therapy with antiarrhythmic medications may be considered.

CVR is an ultrasonographic measurement used as a prognostic tool for fetuses with a prenatal diagnosis of congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM). CVR is calculated using the formula: [(mass length × height × width) × 0.52] / fetal head circumference; all variables should be in centimeters. ∗

Neonatal survival approaches 100% in the absence of hydrops. The CVR identifies fetuses at high risk for developing hydrops, and a CVR greater than 1.6 is associated with an 80% risk of developing hydrops; these fetuses may benefit from closer surveillance and possible fetal intervention. ∗

LHR is an ultrasonographic measurement used in fetuses between 24 and 26 weeks of gestation with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. LHR is calculated according to the following formula: right lung length × right lung length/fetal head circumference; all variables should be in millimeters. ∗

In general, LHR greater than or equal to 1.4 is considered a good prognostic indicator, whereas LHR below 0.6 is associated with poor outcomes. Nevertheless, there is a degree of unpredictability in the clinical course despite an accurate LHR measurement. ∗

The major neonatal diseases that may benefit from fetal intervention are listed in Table 2-2. In utero therapy has been successfully performed for diseases such as primary fetal pleural effusion, lower urinary tract obstruction, neural tube defect, some obstructive heart defects, CCAM, and sacrococcygeal teratoma. Fetal intervention for congenital diaphragmatic hernia is currently investigational. ∗†‡

TABLE 2-2

| FETAL DIAGNOSIS | PEARLS | FETAL INTERVENTION |

| Myelomeningocele | Incidence: 1:2000 live births | In select cases may reduce need for shunting and improve motor outcomes |

| Associated with Arnold–Chiari malformation (ACM) type II | ||

| 70%-85% require ventricular shunt | ||

| 75% have normal intelligence; 50% can live independently | ||

| Overall mortality: 14%; higher if associated with ACM type II | ||

| Congenital diaphragmatic hernia | Incidence: 1:3000-4000 live births | Fetal intervention is currently not recommended outside of ongoing research trials |

| 90% are left sided | ||

| Associated with chromosomal or congenital abnormalities | ||

| If isolated, morbidity is related to degree of pulmonary hypoplasia | ||

| Overall mortality: 26%-68%; higher if associated with other defects | ||

| Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM) | Incidence: 1:25,000-1:35,000 pregnancies Multilobar or bilateral lesions are rare |

Consider in cases of immature fetus with hydrops Options based on fetal maturity and CCAM type Possible options |

| Types: | ||

| n Macrocystic ≥5 mm (single or multiple cysts) | n Fetal resection for microcystic lesion | |

| n Microcystic <5 mm (“solid” appearance) | n Thoracoamniotic shunt for macrocystic lesion | |

| n Mixed | ||

| 10%-15% undergo spontaneous reduction or resolution | ||

| 10%-40% progress to hydrops | ||

| Morbidity is related to size of defect | ||

| Mortality: ≈100% if hydrops develops | ||

| Primary fetal pleural effusion | Incidence: 1:15,000 pregnancies | Possible options |

| 70% are unilateral, usually on the right | Thoracocentesis (in mature fetus) | |

| Good prognostic indicators: isolated, unilateral, or small volume | Shunt placement (in immature fetus with unilateral lesion) | |

| Poor prognostic indicators: hydrops, chromosomal abnormalities, | ||

| or multiple congenital malformations | ||

| Overall mortality: 15%-20% | ||

| Sacrococcygeal teratoma | Incidence: 1:35,000-40,000 live births | Possible options |

| Types: cystic, solid, or mixed | Amnioreduction for polyhydramnios | |

| High risk: high output cardiac failure, hydrops, or placentomegaly | Cyst aspiration if risk of tumor rupture or mass dystocia | |

| Malignancy risk increases with delay in excision | Open fetal resection if high output cardiac failure or hydrops | |

| Morbidity is related to risk of tumor hemorrhage, rupture, or dystocia | ||

| Overall mortality: 45%-100% | ||

| Lower urinary tract obstruction | Incidence: 1% of pregnancies | Consider in fetus who has poor predicted outcome based on ultrasound and urinary fetal electrolyte findings |

| Complications: oligohydramnios, pulmonary hypoplasia, renal dysplasia, and deformational structural anomalies | Possible options | |

| Vesicoamniotic shunt | ||

| Morbidity is related to timing and duration of obstruction | Open vesicostomy | |

| Mortality is correlated with the severity of pulmonary hypoplasia |

39. What are the key principles in determining the potential value of a prenatal therapy for a fetal anomaly?

40. What are the major considerations for fetal intervention in cases of congenital cardiac lesions?

Severe aortic stenosis: Fetal aortic valvuloplasty may reverse left ventricular dysfunction, thereby improving flow through the left side of the heart and left ventricular growth and possibly preventing the development of hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS).

Severe aortic stenosis: Fetal aortic valvuloplasty may reverse left ventricular dysfunction, thereby improving flow through the left side of the heart and left ventricular growth and possibly preventing the development of hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS).

HLHS and intact/restrictive atrial septum: In utero balloon septostomy may increase in utero pulmonary blood flow, thereby decreasing or preventing pathologic pulmonary parenchymal remodeling and possibly reducing the degree of subsequent postnatal pulmonary hypertension.

HLHS and intact/restrictive atrial septum: In utero balloon septostomy may increase in utero pulmonary blood flow, thereby decreasing or preventing pathologic pulmonary parenchymal remodeling and possibly reducing the degree of subsequent postnatal pulmonary hypertension.

Pulmonary atresia/severe pulmonary valve stenosis with intact ventricular septum: In utero balloon valvuloplasty may preserve cardiac function by decompressing the right ventricular load and ensuring adequate right-sided heart blood flow and right ventricular growth. ∗

Pulmonary atresia/severe pulmonary valve stenosis with intact ventricular septum: In utero balloon valvuloplasty may preserve cardiac function by decompressing the right ventricular load and ensuring adequate right-sided heart blood flow and right ventricular growth. ∗

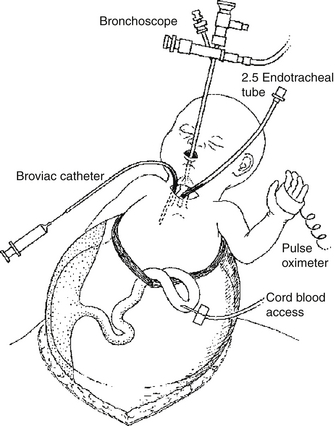

As shown in Figure 2-5, the ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) is a technique by which a mother undergoes partial cesarean delivery so that placental support to the fetus can be maintained while airway identification, stabilization, and, if necessary, mass resection are performed. The procedure is currently used for the delivery and management of fetal airway compromise resulting from extrinsic mass compression or intrinsic airway defect.

Figure 2-5 The ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT). (From Cortes RA, Farmer DL. Recent advances in fetal surgery. Semin Perinatol 2004;28:199–211. [with permission])

Maternal mirror syndrome is a preeclampsia-like state that occurs in the setting of fetal hydrops; other terms that are used interchangeably are Ballantyne syndrome and pseudotoxemia. When the syndrome is identified, immediate delivery is generally indicated. Although the symptoms are similar to those of true preeclampsia, mothers with this syndrome typically exhibit anemia caused by hemodilution rather than hemoconcentration and do not commonly develop thrombocytopenia.

∗ACOG practice bulletin No. 101: Ultrasonography in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:451–61.

†ACOG practice bulletin No. 22: Fetal Macrosomia. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96(3).

∗ACOG practice bulletin No. 22: Fetal Macrosomia. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96(3).

∗ACOG practice bulletin No. 12: Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95(1).

∗ACOG practice bulletin No. 12: Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95(1).

∗ACOG practice bulletin No. 12: Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95(1).

∗ACOG practice bulletin No. 101: Ultrasonography in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:451–61.

†ACOG practice bulletin No. 12: Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95(1).

‡ACOG practice bulletin No. 9: Antepartum Fetal Surveillance. Obstet Gynecol 1999;94(4).

§Turan S, Miller J, Baschat AA. Integrated testing and management in fetal growth restriction. Semin Perinatol 2008 Jun;32(3):194–200.

∗ACOG practice bulletin No. 101: Ultrasonography in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:451–61.

†ACOG practice bulletin No. 12: Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95(1).

‡ACOG practice bulletin No. 9: Antepartum Fetal Surveillance. Obstet Gynecol 1999;94(4).

§Turan S, Miller J, Baschat AA. Integrated testing and management in fetal growth restriction. Semin Perinatol 2008 Jun;32(3):194–200.

∗ACOG practice bulletin No. 12: Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95(1).

†Turan S, Miller J, Baschat AA. Integrated testing and management in fetal growth restriction. Semin Perinatol 2008 Jun;32(3):194–200.

†Galan HL. Timing delivery of the growth-restricted fetus. Semin Perinatol 2011 Oct;35(5):262–9.

∗ACOG practice bulletin No. 12: Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95(1).

∗Lasky RE, Williams AL. The development of the auditory system from conception to term. NeoReviews 2005;6:141–152.

†Lecanuet JP, Schaal B. Fetal sensory competencies. Eur J Obstet Gynecol 1996;68:1–23.

∗ACOG practice bulletin No. 9: Antepartum Fetal Surveillance. Obstet Gynecol 1999;94(4).

∗ACOG practice bulletin No. 9: Antepartum Fetal Surveillance. Obstet Gynecol 1999;94(4).

∗ACOG practice bulletin No. 9: Antepartum Fetal Surveillance. Obstet Gynecol 1999;94(4).

∗ACOG practice bulletin No. 9: Antepartum Fetal Surveillance. Obstet Gynecol 1999;94(4).

∗Manning FA, Snijders R, Harman CR, et al. Fetal biophysical profile score. VI: Correlation with antepartum umbilical venous fetal pH. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993;169:755–763.

∗ACOG practice bulletin No. 101: Ultrasonography in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:451–61.

∗ACOG practice bulletin No. 101: Ultrasonography in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:451–61.

∗Merz E, Abramowicz JS. 3D/4D ultrasound in prenatal diagnosis: is it time for routine use? Clin Obstet Gynecol 2012 Mar;55(1):336–51.

†We JS, Young L, Park IY, et al. Usefulness of additional fetal magnetic resonance imaging in the prenatal diagnosis of congenital abnormalities. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012;286(6):1443–52.

∗Mosquera C, Miller RS, Simpson LL. Twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Semin Perinatol 2012 Jun;36(3):182–9.

∗Mosquera C, Miller RS, Simpson LL. Twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Semin Perinatol 2012 Jun;36(3):182–9.

∗Mosquera C, Miller RS, Simpson LL. Twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Semin Perinatol 2012 Jun;36(3):182–9.

∗Mosquera C, Miller RS, Simpson LL. Twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Semin Perinatol 2012 Jun;36(3):182–9.

∗Cromleholme TM, Coleman B, Hedrick H, et al. Cystic adenomatoid malformation volume ratio predicts outcome in prenatally diagnosed cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung. J Pediatr Surg 2002;37:331–338.

∗Cromleholme TM, Coleman B, Hedrick H, et al. Cystic adenomatoid malformation volume ratio predicts outcome in prenatally diagnosed cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung. J Pediatr Surg 2002;37:331–338.

∗Cromleholme TM, Coleman B, Hedrick H, et al. Cystic adenomatoid malformation volume ratio predicts outcome in prenatally diagnosed cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung. J Pediatr Surg 2002;37:331–338.

∗Laudy JAM, Van Gucht M, Van Dooren MF, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: an evaluation of the prognostic value of the lung-to-head ratio and other prenatal parameters. Prenat Diagn 2003;23:634–639.

∗Laudy JAM, Van Gucht M, Van Dooren MF, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: An evaluation of the prognostic value of the lung-to-head ratio and other prenatal parameters. Prenat Diagn 2003;23:634–639.

∗Adzick NS, Thom EA, Spong CY, et al; MOMS Investigators. A randomized trial of prenatal versus postnatal repair of myelomeningocele. N Engl J Med 2011 Mar 17;364(11):993–1004.

†Arzt W, Tulzer G. Fetal surgery for cardiac lesions. Prenat Diagn 2011 Jul;31(7):695–8.

‡Deprest JA, Nicolaides K, Gratacos E. Fetal surgery for congenital diaphragmatic hernia is back from never gone. Fetal Diagn Ther 2011;29(1):6–17.

∗Ville Y. Fetal therapy: practical ethical considerations. Prenat Diagn 2011 Jul;31(7):621–7.

∗Arzt W, Tulzer G. Fetal surgery for cardiac lesions. Prenat Diagn 2011 Jul;31(7):695–8.