Chapter 32 Fertility Preservation in Cancer Patients

INTRODUCTION

In the modern era of aggressive treatment of malignancies, many cancer survivors will be of reproductive age and wish to resume normal lives. Consequently, fertility preservation has become an increasingly important issue. In addition to the expected difficulties with fertility, obstetrics disorders, such as early pregnancy loss, premature labor, and low birth weight, have also been described after cancer treatment.1

PATIENT POPULATION

The target population is comprised of female and male cancer patients who wish to retain future fertility. Childhood cancer is relatively uncommon, affecting only about 14 of every 100,000 children in the United States each year, and almost 80% of these children survive to adulthood. The most common childhood malignancies are acute lymphoblastic leukemia, central nervous system tumors, and lymphomas. During adolescence, the incidence of osteosarcoma also increases. In the early 20s, the risk of sarcomas and embryonic cancers increases as well.1 In adults, the leading cancers are lung, colon and rectum, and breast, the latter of which is the most common cancer in women. Gynecologic malignancies, lymphomas (including Hodgkin’s disease), melanomas, and bladder cancers are also relatively common. The mainstay of treatment of all of these malignancies remains surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation.

Premature gonadal failure is a well-known consequence of ovarian exposure to chemotherapeutic drugs. A wide variety of malignant and nonmalignant conditions during the reproductive years are treated with gonadotoxic chemotherapy. Although there are several reports of girls under age 16 who have requested preservation of fertility before cancer therapy, the most common malignancy in reproductive-age women that requires immediate fertility intervention is breast cancer.2,3 Fifteen percent of all breast cancer cases are estimated to occur in women younger than age 40.4

Premature gonadal failure is also a well-known consequence of ovarian exposure to radiation. In general, radiotherapy is used cautiously in children and adolescents because of its late sequelae on immature and developing tissues.1 Pelvic radiotherapy is most commonly used to provide local disease control for solid tumors, including tumors of the bladder, rectum, uterus, cervix, and vagina, all of which are more common in adult women. Cervical cancer is perhaps the most common malignancy in reproductive-age women desiring fertility-preserving intervention. It is estimated that 50% of the 13,000 women newly diagnosed with cervical cancer in the United States will be younger than age 35.5

CHEMOTHERAPY AND OVARIAN DAMAGE

Cytotoxic Drug Targets

The menstrual dysfunction that occurs during chemotherapy is not always due to the direct toxic effects on the ovary. Severe illness, malnutrition, and general mental and physical stress can interfere with normal function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. Short-term disruption of a menstrual cycle can also be the result of destruction of growing follicles rather than primordial follicles. Destruction of all growing follicles will delay menses for at least 3 months, because it takes a primordial follicle approximately 85 days to reach the stage of ovulation.

Risk Factors for Gonadal Damage

The most important risk factors for gonadal damage are the age of the patient, the drug class, and cumulative dose of the drug. The risk of gonadal damage increases with the age of the woman. This is most likely due to the presence of fewer remaining oocytes compared to younger patients. In one study of women who had received mechlorethamine, Oncovin (vincristine), procarbazine, and prednisone (MOPP protocol) for Hodgkin’s disease, the subsequent amenorrhea rate was 20% for women younger than age 25, compared to 45% for those at least 25 years old.6 In another study, the overall incidence of premature ovarian failure after MOPP chemotherapy was 61%.7

Cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents are not equally gonadotoxic. Cell-cycle nonspecific chemotherapeutic agents are considered to be more gonadotoxic than cell-cycle specific ones (Table 32-1). Alkylating agents are among the most gonadotoxic of these cell-cycle nonspecific drugs, and women who have received high-dose alkylating agent therapy are at highest risk for premature ovarian failure. Cyclophosphamide is considered to be the most gonadotoxic member of this category.

* Female gonads; male gonads may have different sensitivity. Many drugs have unknown risks.

Predicting Ovarian Failure

Premature ovarian failure does not consistently occur in patients receiving multiagent chemotherapy, regardless of age or type of chemotherapeutic agent. Most young patients with Hodgkin’s disease treated with multiagent chemotherapy and radiation to a field that does not include the ovaries will be fertile, although their fertility will begin to decrease at a younger age than matched controls.8 A spontaneous conception was reported in a young woman with premature ovarian failure after 14 courses of an alkylating agent combined with pelvic irradiation for treatment of Ewing’s sarcoma of the pelvis.9 This exemplifies the difficulties in predicting the probability of ovarian failure after chemotherapy, which also makes it difficult to evaluate the efficacy of treatment aimed at preserving ovarian function.

Markers for Gonadal Damage

Serum Markers

Cancer chemotherapy is associated with a transient suppression of inhibin B in prepubertal girls. Consequently, inhibin B levels, together with sensitive measurements of FSH, are potential markers of the gonadotoxic effects of cancer chemotherapy in prepubertal girls.10

Ultrasonographic Markers

Another method to assess ovarian reserve in these patients is ultrasonographic determination of ovarian volume and antral follicle count.11 Cancer survivors with normal ovarian function tend to have normal antral follicle counts, although their ovarian volumes are often smaller than controls.

RADIOTHERAPY AND DAMAGE TO PELVIC ORGANS

Pelvic radiotherapy damages both the ovaries and the uterus. Ovarian damage from radiotherapy results in impaired fertility and premature ovarian failure.11–19 Radiation therapy–induced uterine damage manifests as impaired growth and blood flow.20 The effects on subsequent pregnancies can be substantial.

Ovarian Damage

The ovarian follicles are remarkably vulnerable to DNA damage from ionizing radiation. Radiation therapy results in ovarian atrophy and reduced follicle stores.18 As a result, serum FSH and luteinizing hormone (LH) levels progressively rise and estradiol levels decline within 4 to 8 weeks after radiation exposure.

However, a recent study suggested the presence of germline stem cells in the adult ovary.19 If these findings are confirmed by others, they leave open the possibility that new oocytes might be able to be regenerated after depletion by chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

Risk Factors for Ovarian Damage

Cancer patients are at high risk for premature ovarian failure after treatment with pelvic or total body radiation. The degree of ovarian damage is related to the patient’s age and the total dose of radiation to the ovaries (Table 32-2). For example it may take 12 Gray (Gy; 1 rad = 1 cGy) to induce permanent ovarian failure in prepubertal girls and only 2 Gray to achieve the same result in women older than age 45.12 It is generally estimated that a single dose of 6.5 to 8.0 Gy will cause permanent ovarian failure in most postpubertal women.13

Table 32-2 Determinants of Radiation-induced Gonadal Failure

| Age of patient |

A dose-dependent reduction in the primordial follicle pool occurs when exposing ovaries to radiotherapy. It is estimated that as little as 3 Gy is enough to destroy 50% of the oocyte population in young reproductive-age women.14

The dose-response of the ovaries to irradiation has been demonstrated in several studies.15–17 When the mean radiation dose to the ovary was 1.2 Gy, 90% of patients retained their ovarian function. When the mean dose was 5.2 Gy, only 60% retained ovarian function. Ovarian failure will occur in virtually all patients exposed to pelvic radiation at doses necessary to treat cervical cancer (85 Gy) or rectal cancer (45 Gy) or to total body radiation for bone marrow transplantation (8 to 12 Gy to the ovaries). The addition of chemotherapy to radiotherapy further decreases the dose required to induce premature ovarian failure.

Uterine Damage

Pregnancy after Radiation Therapy

Pregnancies achieved by survivors of childhood cancer who have received pelvic irradiation must be considered high risk due to the uterine factor.20,21 Common obstetric problems reported in these patients include early pregnancy loss, premature labor, and low birthweight infants.

FERTILITY PRESERVATION STRATEGIES

Pharmacologic Protection

Gonadotropin-releasing Hormone (GnRH) Agonists

One of the first strategies attempted was to mimic the premenarchal state by administering GnRH agonists.22,23 This was based on the observation that ovaries of premenarchal girls are less sensitive to cytotoxic drugs than adult ovaries. The hypothesis is that suppressing FSH and LH elevation will inhibit the normal physiologic loss of primordial follicles by recruitment and subsequent atresia. Other possibilities include a protective effect of decreased ovarian perfusion secondary to the resultant hypoestrogenic milieu or a direct gonadal effect mediated through sphingosine-1-phosphate or germline stem cell preservation.24

The most compelling study of this approach to date was performed in primates. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial using rhesus monkeys demonstrated that administration of GnRH agonists protected the ovary against cyclophosphamide-induced damage.25

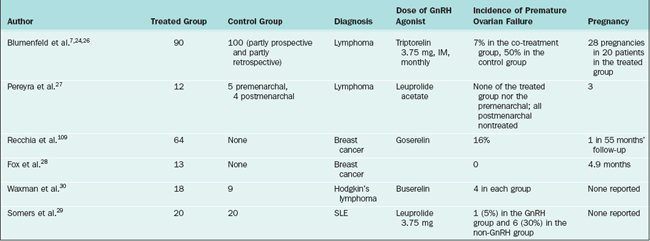

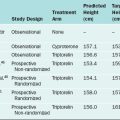

Several human studies have also shown promising results (Table 32-3). In the largest study, 90 lymphoma patients treated with chemotherapy and GnRH agonists had a premature ovarian failure rate of 7% compared to a 30% rate for patients treated with chemotherapy alone.7 Similar results were reported by others.26–29 One small prospective, controlled study of 18 women showed that GnRH agonists were not effective in the prevention of premature ovarian failure.30

Some investigators have questioned the theoretical value of GnRH agonist gonadal suppression in preserving ovarian function in susceptible patients.31,32 Research has shown that primordial follicles initiate follicle growth through an unknown mechanism, which is gonadotropin independent.33 GnRH-1 receptor is expressed on the human ovary, but its physiologic or pharmacologic role is unclear. However, 80% of human ovarian cancers express GnRH receptor and both GnRH agonists and antagonists inhibit the proliferation of cancer cell lines.34

Another important fact is that although mRNA expression for FSH receptors has been identified in human primordial follicles, there is no report of identification of the FSH receptor protein in these follicles.35 FSH receptor protein is uniformly present in as early as 3–4 granulosa layer preantral follicles.31 Consequently, it is possible that GnRH analogues preserve only follicles that have initiated growth, which constitute less than 10% of all the follicular pool at any given time in the ovary. Once follicle growth has been initiated, each follicle is destined either to undergo atresia or to ovulate. It is quite possible that GnRH agonist cotreatment delays the fate of these follicles, hence giving the impression that ovarian function is protected in the short run.

A final observation that suggests that GnRH therapy might not work is that prepubertal children receiving heavy chemotherapy still suffer from ovarian failure.36 Meirow proposed that because younger patients have a larger ovarian reserve, absence of immediate ovarian failure does not mean that gonads are unaffected by the chemotherapy37 but simply that the patient has a sufficient number of oocytes not to demonstrate immediate failure. Given the above-mentioned arguments and counterarguments, a prospective, randomized study with sufficient power will appropriately evaluate the effectivness of GnRH analogues as a potential strategy for fertility preservation.

Oral Contraceptive Pill and Progestins

Unfortunately, suppressive therapy with a variety of oral steroids such as oral contraceptives or progestins has not been shown to be effective in preventing damage from chemotherapy or radiation therapy.38–41

Apoptotic Inhibitors: A New Research Direction

Inhibition of apoptosis signaling events could potentially stop the apoptotic process and protect the patient from premature ovarian failure. Apoptosis plays an essential role in germ cell dynamics, both prenatally and postnatally.42,43 Moreover, apoptosis could be activated aberrantly via chemotherapeutic drugs.44,45

Sphingosine-1-phosphate may be an example of an apoptotic inhibitor. Ceramide is a sphingolipid molecule believed to be an early messenger signaling apoptosis in response to stress. It was shown that oocytes of mice that lacked the enzyme to generate ceramide, acid sphingomyelinase, and wild type mice oocytes that had been treated with sphingosine-1-phosphate therapy resisted apoptosis induced by doxorubicin.46

OVARIAN TRANSPOSITION

Transposing the ovaries out of the field of irradiation appears to help to maintain ovarian function in patients scheduled to undergo gonadotoxic radiotherapy. Transposing the ovaries reduced the radiation dose to each ovary compared to ovaries left in their original location.47 Transposed ovaries received a dose of 126 cGy during intracavitary radiation, 135 to 90 cGy during external radiation therapy with a total dose of 4500 cGy, and 230 to 310 cGy during para-aortic node irradiation with a dose of 4500 cGy.48

Lateral versus Medial Transposition

Lateral transposition appears to be more effective than medial transposition. Initial experience with medial transposition (i.e., suturing the ovaries posterior to the uterus and shielding them during treatment) showed that this approach is generally ineffective. A compilation of 10 case reports and small series showed an ovarian failure rate of 14% after lateral transposition compared to 50% after medial transposition.49

One study compared 7 cervical cancer patients who underwent lateral ovarian transposition to 9 Hodgkin’s disease patients who underwent medial transposition, all of whom underwent radiation therapy.50 Six of the 7 patients with lateral transposition were shown to have ovaries outside the field by computed tomography (CT), and all retained ovarian function. Scattered doses to the ovaries were calculated to be 100 to 300 cGy. The 1 patient with ovaries within the field received 450 cGy and developed ovarian failure. After medial transposition, CT showed that only 3 of the 13 ovaries were outside the field. Even the 3 ovaries outside the field received approximately 300 cGy.

Lateral Ovarian Transposition

There are several advantages to laparoscopic transposition; as a result, this approach has become the most common. Laparoscopic transposition can be performed as an outpatient procedure with little disruption of the planned therapeutic schedule. The ability to do this easily will eliminate unnecessary transposition in the majority of cervical cancer cases where radiation therapy is not required. An important advantage of laparoscopic ovarian transposition is that radiation therapy can be initiated immediately postoperatively, preventing failure due to the ovaries migrating back to the irradiation field.17,51,52 In cases of vaginal or cervical cancers being treated by brachytherapy, laparoscopic ovarian transposition can be performed under the same anesthetic for inserting the brachytherapy device.53

Surgical Technique for Lateral Ovarian Transposition

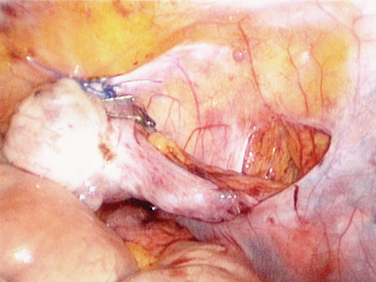

The surgery starts with transection of the utero-ovarian ligament and uterine tube. The adnexa are mobilized with the ovarian vessels to the paracolic gutters. Ideally, the vascular pedicles are kept retroperitoneal to avoid tension, torsion, or trauma and bowel herniation while the ovaries remain intraperitoneal to reduce cyst formation (Fig. 32-1).54 The ovary is then sutured with nonabsorbable suture to the posterior abdominal peritoneum. Clips are placed so that the radiotherapist can assess where the ovaries are located.

A different technique for ovarian transposition has been reported that requires less mobilization of the ovary. After transection of the utero-ovarian ligament, the ovary is not separated from the uterine tube and the ovarian vessels are completely mobilized. Although this approach has been described in a case report to have resulted in a spontaneous pregnancy,55 the technique may not allow sufficient movement of the ovaries out of the radiation field in most cases of malignancies requiring pelvic radiation if the purpose is to keep it close to the extended uterine tube. It is unlikely that a uterine tube would stretch as far as the anterior superior iliac spine.

High mobilization of the ovaries without the tube has been described by Morice and colleagues.15 In this technique, the tube is not detached from the uterus but is separated from the ovary. The ovary is detached and the ovarian vessels dissected to the aortic bifurcation. The pedicle is then rotated and attached to the paracolic gutters.

Success Rates

Most ovaries will maintain function if they are transposed at least 3cm from the upper edge of the field.56 The dose of radiation that ovaries receive after transposition has been calculated. It has been shown that when cervical cancer is treated with a radiation dose of 4,000 cGy, ovaries 3cm from the radiation field edge receive 280 cGy and those 4cm from the field edge receive 200 cGy due to scatter.57 One study found that ovaries will maintain function when transposed above the iliac crest.58

It has been shown that approximately 80% of women undergoing laparoscopic ovarian transposition will maintain ovarian function after radiation therapy for various indications.59 The majority of women with Stage I and II Hodgkin’s disease treated with radiation alone or with minimal chemotherapy after laparoscopic ovarian transposition will retain their ovarian function and fertility.17

Causes of Failure

Ovarian failure after transposition can be on the basis of several different mechanisms. Ovarian failure may result if the ovaries are not moved far enough out of the radiation field. Another reason for failure would be ovarian migration back to their original position. This may occur if absorbable suture is used. Ovarian failure after transposition may also be due to compromised ovarian blood flow from surgical technique or radiation injury to the vascular pedicle.60 Another concern with ovarian transposition is the development of symptomatic ovarian cysts. The mechanism causing the cysts is unknown but they can be surpressed with oral contraceptives.60

Fertility After Radiotherapy

Pregnancies occur after radiotherapy regardless of pretreatment ovarian transposition. In a study of 37 women, 15% became pregnant after brachytherapy with or without external radiation for vaginal or cervical clear cell carcinoma, and 80% became pregnant after external radiation for dysgerminomas and pelvic sarcomas.62 Interestingly, 75% occurred without repositioning the ovaries.

Pregnancy Outcome After Radiotherapy

Several papers addressed pregnancy outcomes after pelvic radiation therapy. In a study of 31,150 atomic bomb survivors, there was no increase in stillbirth, major congenital malformations, chromosomal abnormalities, or mutations.48 Likewise, in women treated with radiotherapy for Hodgkin’s disease addition, there was no increase in stillbirths, low birthweight, congenital malformations, abnormal karyotypes, or cancer.63 However, one study found an increase in low birthweight and spontaneous abortions if conception occurred less than a year after radiation exposure.64 On this basis, it seems reasonable to advise delaying pregnancy for a year after completing radiation therapy.

ASSISTED REPRODUCTIVE TECHNOLOGY

Oocyte Cryopreservation

The option of oocyte cryopreservation before fertilization for later IVF is considered an experimental technique and should only be performed under investigational protocol.65 Most results using this approach have been disappointing, with low survival, fertilization, and pregnancy rates after IVF of thawed oocytes.66 However, in women without partners, freezing mature or immature oocytes may be the only practical option.

The main factor responsible for this outcome is the structural complexity of oocytes, which makes successful cryopreservation difficult. Oocyte subcellular organelles are far more complex and perhaps more sensitive to thermal injury than in preimplantation embryos.67,68

Recent series have demonstrated limited success rates for this approach.69–71 Either ethylene glycol or dimethylsulfoxide can be used as a cryprotectant before freezing in liquid nitrogen.69,71 Duration of oocyte storage does not seem to interfere with oocyte survival.72 On thawing, the reported mean survival rate is 68%, and the fertilization rate 48%. The pregnancy rate per thawed oocyte has been less than 2%. There have been only a limited number of established pregnancies and deliveries resulting from cryopreserved oocytes. There appears to be no increase in chromosomal abnormalities, birth defects, or developmental deficits in the children born from cryopreserved oocytes.65

Embryo Cryopreservation after IVF

The post-thaw survival rate of embryos ranges between 35% and 90%, implantation rates between 8% and 30%, and cumulative pregnancy rates can be greater than 60%.73,74 In practice, the delivery rate after transfer of previously cryopreserved embryos is approximately 19% per embryo.75

Alternative Methods for Ovarian Stimulation Before IVF

There is some concern that delay of chemotherapy and the high estrogen levels obtained during an IVF cycle may decrease long-term survival for breast cancer patients. Typically there is an interval of 6 weeks between surgery and the initiation of chemotherapy for breast cancer. Several strategies have been used in an attempt to obtain oocytes for IVF in the least amount of time with the lowest estradiol levels.76–82 Women who cryopreserved all embryos before chemotherapy produced more oocytes and embryos than those who had IVF after chemotherapy.83

As a result, some centers use natural cycle (unstimulated) recruitment prior to IVF for breast cancer patients. A single oocyte is usually aspirated. However, cancellation rates are high and pregnancy rates are very low (7.2% per cycle and 15.8% per embryo transfer).77,78

Others have used a short flare protocol rather than the standard protocol to minimize the time required to achieve follicle recruitment before IVF.76 For this technique, the initial increase in ovarian stimulation seen immediately after initiation of GnRH agonist therapy is utilized rather than waiting for the subsequent pituitary down-regulation that predictably occurs after weeks of agonist therapy.

Another approach is to stimulate the ovaries before IVF with tamoxifen, a nonsteroidal antiestrogen, commonly used as a breast cancer chemopreventive agent.78 In a manner similar to clomiphene citrate, tamoxifen (40–60 mg) is started on day 2 or 3 of the cycle and given daily for 5 to 12 days. Compared to natural cycle IVF, tamoxifen will result in a significantly higher number of mature oocytes, peak estradiol, and embryos (mean of 1.6 embryos versus 0.6 embryos).78

Letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, has been recently introduced as a promising ovulation induction agent.80 Letrozole competitively inhibits the activity of aromatase, thus preventing the conversion of androgenic substances to estrogens. Letrozole is used in the treatment of advanced-stage postmenopausal breast cancer, because it suppresses plasma estrogen levels at doses as low as 0.1 mg/day.81 For ovulation induction before IVF, letrozole can be used independently or in combination with FSH.82

This approach is the most promising of all procedures because it requires no stimulation and minimal delay, and routine implementation requires further trials. A study of 29 women with breast cancer found similar cancer recurrence rates in those who underwent ovarian stimulation for IVF compared to those who do not.83 However, the ultimate utility of this approach is yet to be established.

CRYOPRESERVATION OF OVARIAN TISSUE

Ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation is an experimental procedure introduced to preserve fertility in women with threatened reproductive potential.84 Unlike a suspended single cell, tissue cryopreservation presents serious physical constraints related to heat and mass transfer and potential formation of ice crystals, which is responsible for the freeze– thaw injury.85 Consequently, better survival is expected from primordial follicles because of their smaller size and lack of follicular fluid.

As in other reproductive technologies, animal models have provided useful information when transferring methods to treat human infertility. With the sheep ovary providing a reliable tool, Gosden and associates pioneered the sheep ovarian transplantation model. Using cryopreserved–thawed ovarian cortical strips, they showed follicular survival and endocrine function, as well as restoration of fertility after transplantation of cryopreserved– thawed ovarian cortical strips.86,87

Autotransplantation

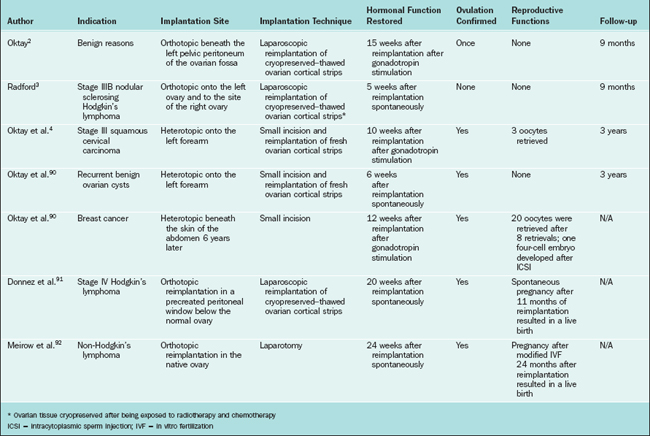

Cryopreserved ovarian tissue can be transplanted back into the patient. The potential for reintroduction of a cancer nidus may limit this use in malignancies known to have a predilection for the ovaries, including leukemias and potentially breast cancers. Using present techniques, ovarian tissue strips are removed from the patient before chemotherapy. They are frozen in small strips. When the patient is ready for pregnancy they are transplanted back into the patient in heterotopic or orthotopic sites. Because this is an avascular graft, ischemic injury to the transplanted tissue results in the loss of virtually the entire growing follicle population and a significant number of primordial follicles. A summary of the experience with ovarian autotransplantation is given in Table 32-4.

Several different surgical techniques have been developed for transplantation of ovarian cortical strips. In a patient with benign disease who required oophorectomy, strips of her own ovaries were subsequently transplanted into the pelvis.31 Ovarian function ceased within the first 9 months. In a 36-year-old breast cancer survivor, her own previously frozen ovarian tissue was transplanted underneath the lower abdominal skin, resulting in restoration of hormonal function.88 After multiple ovarian stimulation cycles, percutaneous oocyte aspiration followed by IVF resulted in the generation of a four-cell embryo that was transferred but did not result in pregnancy.

Two cases of live birth after ovarian autotransplantation have been reported.89,90 In both cases, ovarian tissue was harvested before chemotherapy for Hodgkin’s lymphoma and was reimplanted into the residual ovary in the pelvis. Both patients re-established ovulation and became pregnant after reimplantation without medical assistance.

The fact that the tissue was reimplanted into the native ovary does not exclude the possibility that ovarian function resumed from areas in the ovary that had not been removed and reimplanted. Spontaneous pregnancies have occurred in women with premature ovarian failure after chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy.6,9 This illustrates the fact that it is impossible to know the exact site of origin of the oocytes that led to pregnancies after reimplantation.

One of the potential limitations of ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation is loss of a large fraction of follicles during the initial ischemia after transplantation.87,91,92 Previous work indicated that whereas loss due to freezing is relatively small, up to two thirds of follicles are lost subsequent to transplantation. Given this limitation, it has been recommended that ovarian tissue freezing should be restricted to patients younger than age 35.31

Research should focus on refinement of cryopreservation protocols, better cryoprotectants, transplantation techniques that decrease ischemia, and determination of the ideal transplantation site.93–95 The practice committee of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine recommends that ovarian tissue cryopreservation or transplantation procedures should be performed only as experimental procedures under Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidelines.65

The Future

Xenografts

Transplantation studies in severe combined immunodeficient mice clearly show that follicle maturation and completion of meiosis I in preparation for ovulation and potential fertilization can occur in xenografts.96 Concerns regarding viral infections as well as general ethical reservations may limit the use of this option in clinical practice.

FERTILITY PRESERVATION IN GYNECOLOGIC MALIGNANCIES

FERTILITY PRESERVATION STRATEGIES IN THE MALE

Semen Cryopreservation

Semen cryopreservation followed by banking is the most commonly used option for fertility preservation after cancer therapy; it yields good results and provides a chance of establishing pregnancy. Patients diagnosed with cancer used to be considered poor candidates for sperm cryopreservation because they may present with disease-induced suboptimal semen quality and cryosensitivity. However, the deterioration in semen quality after cryopreservation–thawing in patients with cancer is similar to that of normal donors.97

Chemotherapy

Choice of Cytotoxic Regimens

Probably the common chemotherapy combination with the least effect on spermatogenesis is the NOVP regimen (Novantrone [mitoxantrone], Oncovin [vincristine], vinblastine, prednisone).98 Sperm production has been reported to recover rapidly within 3 to 4 months after receiving this multidrug chemotherapy despite its adverse effects on spermatogenesis.99 This rapid recovery is due to the fact that this combination damages spermatogenic germ cells but does not destroy stem cells.100

The MOPP regimen (mechlorethamine, Oncovin [vincristine], procarbazine, and prednisone) appears to have the most detrimental effects on spermatogenesis and should be avoided when possible. MOPP has been reported to permanently impair spermatogenesis in long-term cancer survivors and can lead to constant azoospermia for at least 14 months after completion of treatment in adults.103 Similarly, ChlVPP (chlorambucil, vinblastine, procarbazine, and prednisolone) can lead to irreversible damage to the germinal epithelium. Persisting high FSH levels were detected for up to 17 years after the end of therapy in patients who received ChlVPP.104

The doses of cytotoxic drugs used also play a significant role in determining the fate of spermatogenesis after therapy. Approximately 70% of patients receiving doses less than 7.5g/m2 of cyclophosphamide recovered, but only 10% recovered when doses exceeded 7.5g/m2.105

Testosterone Suppressors

Testosterone suppressors, such as gonadal steroids, GnRH analogues, and antiandrogens, may be tried before and during cytotoxic therapy to enhance the recovery of spermatogenesis and fertility.106 Although studies on rodent models offered promising results, clinical trials do not currently support these findings.

Gonadal Shielding for Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is significantly more toxic to testes than to ovaries. Doses as low as 0.1 Gy can have detectable effects on spermatogenesis in adult men, with doses over 2 Gy causing more permanent damage.107 Somatic cells are more resistant to chemotherapy- and radiation-induced damage than are germ cells. Indeed, Leydig cell function is not impaired until doses of 20 Gy are administered to the prepubertal boy and up to 30 Gy in sexually mature males.108

Testicular Tissue Harvesting

1 You W, Dainty LA, Rose GS, et al. Gynecologic malignancies in women aged less than 25 years. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1405-1409.

2 Oktay K, Karlikaya G. Ovarian function after transplantation of frozen, banked autologous ovarian tissue. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1919.

3 Radford JA, Lieberman BA, Brison DR, et al. Orthotopic reimplantation of cryopreserved ovarian cortical strips aftter high-dose chemotherapy for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Lancet. 2001;357:1172-1175.

4 Oktay K, Economos K, Kan M, et al. Endocrine function and oocyte retrieval after autologous transplantation of ovarian cortical strips to the forearm. Jama. 2001;286:1490-1493.

5 Waggoner SE. Cervical cancer. Lancet. 2003;361:2217-2225.

6 Schilsky RL, Sherins RJ, Hubbard SM, et al. Long-term follow up of ovarian function in women treated with MOPP chemotherapy for Hodgkin’s disease. Am J Med. 1981;71:552-556.

7 Blumenfeld Z, Avivi I, Linn S, et al. Prevention of irreversible chemotherapy-induced ovarian damage in young women with lymphoma by a gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonist in parallel to chemotherapy. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:1620-1626.

8 Multidisciplinary Working Group convened by the British Fertility Society. A strategy for fertility services for survivors of childhood cancer. Hum Fertil. 2003;6:A1-A40.

9 Bath LE, Tydeman G, Critchley HO, et al. Spontaneous conception in a young woman who had ovarian cortical tissue cryopreserved before chemotherapy and radiotherapy for a Ewing’s sarcoma of the pelvis: Case report. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2569-2572.

10 Crofton PM, Thomson AB, Evans AE, et al. Is inhibin B a potential marker of gonadotoxicity in prepubertal children treated for cancer? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2003;58:296-301.

11 Bath LE, Wallace WH, Shaw MP, et al. Depletion of ovarian reserve in young women after treatment for cancer in childhood: Detection by anti-Müllerian hormone, inhibin B and ovarian ultrasound. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2569-2572.

12 Lushbaugh C, Casarett GW. The effects of gonadal irradiation in clinical radiation therapy: A review. Cancer. 1976;37(Suppl 2):1111-1125.

13 Perez CA, Purdy JA, Li Z, Hall EJ. Biologic and physical aspects of radiation oncology. In: Hoskins WJ, Perez CA, Young RC, et al, editors. Principles and Practice of Gynecologic Oncology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:446-447.

14 Wallace WH, Thomson AB, Saran F, Kelsey TW. Predicting age of ovarian failure after radiation to a field that includes the ovaries. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:738-744.

15 Morice P, Juncker L, Rey A, et al. Ovarian transposition for patients with cervical carcinoma treated by radiosurgical combination. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:743-748.

16 Gaetini A, De Simone M, Urgesi A, et al. Lateral high abdominal ovariopexy: An original surgical technique for protection of the ovaries during curative radiotherapy for Hodgkin’s disease. J Surg Oncol. 1988;39:22-28.

17 Williams RS, Littell RD, Mendenhall NP. Laparoscopic oophoropexy and ovarian function in the treatment of Hodgkin disease. Cancer. 1999;86:2138-2142.

18 Meirow D, Schenker JG, Rosler A. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome with low oestradiol in non-classical 17α-hydroxylase, 17,20-lyase deficiency: What is the role of oestrogens? Hum Reprod. 1996;11:2119-2121.

19 Johnson J, Canning J, Kaneko T, et al. Germline stem cells and follicular renewal in the postnatal mammalian ovary. Nature. 2004;428:145-150.

20 Critchley HO, Wallace WH. Impact of cancer treatment on uterine function. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;34:64-68.

21 Bath LE, Wallace WH, Critchley HO. Late effects of the treatment of childhood cancer on the female reproductive system and the potential for fertility preservation. BJOG. 2002;109:107-114.

22 Chiarelli AM, Marrett LD, Darlington G. Early menopause and infertility in females after treatment for childhood cancer diagnosed in 1964–1988 in Ontario, Canada. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:245-254.

23 Tangir J, Zelterman D, Ma W, et al. Reproductive function after conservative surgery and chemotherapy for malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:251-257.

24 Blumenfeld Z. Ovarian cryopreservation versus ovarian suppression by GnRH analogues: Primum non nocere. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1924-1925.

25 Ataya K, Rao LV, Lawrence E, et al. Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist inhibits cyclophosphamide-induced ovarian follicular depletion in rhesus monkeys. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:365-372.

26 Blumenfeld Z, Dann E, Avivi I, et al. Fertility after treatment for Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:138-147.

27 Pereyra Pacheco B, Mendez Ribas JM, Milone G, et al. Use of GnRH analogs for functional protection of the ovary and preservation of fertility during cancer treatment in adolescents: A preliminary report. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81:391-397.

28 Fox KR, Ball JE, Mik R, Moore HC. Prevention of chemotherapy-associated amenorrhea (CRA) with leuprolide in young women with early stage breast cancer (Abstract). Proc Ann Soc Clin Oncol. 25a, 2001.

29 Somers EC, Marder W, Christman GM, et al. Use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog for protection against premature ovarian failure during cyclophosphamide therapy in women with severe lupus. Arthr Rheum. 2005;52:2761-2767.

30 Waxman JH, Ahmed R, Smith D, et al. Failure to preserve fertility in patients with Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1987;19:159-162.

31 Sonmezer M, Oktay K. Fertility preservation in female patients. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10:251-266.

32 Oktay K, Sonmezer M, Oktem O. “Ovarian cryopreservation versus ovarian suppression by GnRH analogues: Primum non nocere”: Reply. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1681-1683.

33 Meduri G, Touraine P, Beau I, et al. Delayed puberty and primary amenorrhea associated with a novel mutation of the human follicle-stimulating hormone receptor: Clinical, histological, and molecular studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3491-3498.

34 Emons G, Grundker C, Gunthert AR, et al. GnRH antagonists in the treatment of gynecological and breast cancers. Endoc-Rel Cancer. 2003;10:291-299.

35 Oktay K, Briggs D, Gosden RG. Ontogeny of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene expression in isolated human ovarian follicles. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3748-3751.

36 Teinturier C, Hartmann O, Valteau-Couanet D, et al. Ovarian function after autologous bone marrow transplantation in childhood: High-dose busulfan is a major cause of ovarian failure. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;22:989-994.

37 Meirow D, Lewis H, Nugent D, et al. Subclinical depletion of primordial follicular reserve in mice treated with cyclophosphamide: Clinical importance and proposed accurate investigative tool. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1903-1907.

38 Chapman RM, Sutcliffe SB. Protection of ovarian function by oral contraceptives in women receiving chemotherapy for Hodgkin’s disease. Blood. 1981;58:849-851.

39 Whitehead E, Shalet SM, Blackledge G, et al. The effect of combination chemotherapy on ovarian function in women treated for Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer. 1983;52:988-993.

40 Montz FJ, Wolff AJ, Gambone JC. Gonadal protection and fecundity rates in cyclophosphamide-treated rats. Cancer Res. 1991;51:2124-2126.

41 Familiari G, Caggiati A, Nottola SA, et al. Ultrastructure of human ovarian primordial follicles after combination chemotherapy for Hodgkin’s disease. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:2080-2087.

42 Tilly JL. Apoptosis and ovarian function. Rev Reprod. 1996;1:162-172.

43 Tilly JL. The molecular basis of ovarian cell death during germ cell attrition, follicular atresia, and luteolysis. Front Biosci. 1996;1:d1-d11.

44 Morita Y, Tilly JL. Oocyte apoptosis: Like sand through an hourglass. Dev Biol. 1999;213:1-17.

45 Tilly JL. Molecular and genetic basis of normal and toxicant-induced apoptosis in female germ cells. Toxicol Lett. 1998;102–103:497-501.

46 Morita Y, Perez GI, Paris F, et al. Oocyte apoptosis is suppressed by disruption of the acid sphingomyelinase gene or by sphingosine-1–phosphate therapy. Nat Med. 2000;6:1109-1114.

47 Howell SJ, Shalet SM. Fertility preservation and management of gonadal failure associated with lymphoma therapy. Curr Oncol Rep. 2002;4:443-452.

48 Covens AL, van der Putten HW, Fyles AW, et al. Laparoscopic ovarian transposition. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1996;17:177-182.

49 Howard FM. Laparoscopic lateral ovarian transposition before radiation treatment of Hodgkin disease. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997;4:601-604.

50 Hadar H, Loven D, Herskovitz P, et al. An evaluation of lateral and medial transposition of the ovaries out of radiation fields. Cancer. 1994;74:774-779.

51 Treissman MJ, Miller D, McComb PF. Laparoscopic lateral ovarian transposition. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:1229-1231.

52 Yarali H, Demirol A, Bukulmez O, et al. Laparoscopic high lateral transposition of both ovaries before pelvic irradiation. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7:237-239.

53 Clough KB, Goffinet F, Labib A, et al. Laparoscopic unilateral ovarian transposition prior to irradiation: Prospective study of 20 cases. Cancer. 1996;77:2638-2645.

54 Anderson B, LaPolla J, Turner D, et al. Ovarian transposition in cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1993;49:206-214.

55 Bisharah M, Tulandi T. Laparoscopic preservation of ovarian function: An underused procedure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:367-370.

56 Bidzinski M, Lemieszczuk B, Zielinski J. Evaluation of the hormonal function and features of the ultrasound picture of transposed ovary in cervical cancer patients after surgery and pelvic irradiation. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1993;14:77-80.

57 van Beurden M, Schuster-Uitterhoeve AL, Lammes FB. Feasibility of transposition of the ovaries in the surgical and radiotherapeutical treatment of cervical cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1990;16:141-146.

58 Chambers SK, Chambers JT, Kier R, et al. Sequelae of lateral ovarian transposition in irradiated cervical cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;20:1305-1308.

59 Morice P, Castaigne D, Haie-Meder C, et al. Laparoscopic ovarian transposition for pelvic malignancies: Indications and functional outcomes. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:956-960.

60 Feeney DD, Moore DH, Look KY, et al. The fate of the ovaries after radical hysterectomy and ovarian transposition. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;56:3-7.

61 Chambers SK, Chambers JT, Holm C, et al. Sequelae of lateral ovarian transposition in unirradiated cervical cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;39:155-159.

62 Morice P, Thiam-Ba R, Castaigne D, et al. Fertility results after ovarian transposition for pelvic malignancies treated by external irradiation or brachytherapy. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:660-663.

63 Swerdlow AJ, Jacobs PA, Marks A, et al. Fertility, reproductive outcomes, and health of offspring, of patients treated for Hodgkin’s disease: An investigation including chromosome examinations. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:291-296.

64 Fenig E, Mishaeli M, Kalish Y, et al. Pregnancy and radiation. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27:1-7.

65 Ovarian tissue and oocyte cryopreservation. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:993-998.

66 Oktay K, Kan MT, Rosenwaks Z. Recent progress in oocyte and ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2001;13:263-268.

67 Magistrini M, Szollosi D. Effects of cold and of isopropyl-N-phenylcarbamate on the second meiotic spindle of mouse oocytes. Eur J Cell Biol. 1980;22:699-707.

68 Stachecki JJ, Cohen J, Willadsen S. Detrimental effects of sodium during mouse oocyte cryopreservation. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:395-400.

69 Katayama KP, Stehlik J, Kuwayama M, et al. High survival rate of vitrified human oocytes results in clinical pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:223-224.

70 Liebermann J, Tucker MJ, Sills ES. Cryoloop vitrification in assisted reproduction: Analysis of survival rates in > 1000 human oocytes after ultra-rapid cooling with polymer augmented cryoprotectants. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2003;30:125-129.

71 Yoon TK, Kim TJ, Park SE, et al. Live births after vitrification of oocytes in a stimulated in vitro fertilization–embryo transfer program. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1323-1326.

72 Porcu E, Fabbri R, Damiano G, et al. Oocyte cryopreservation in oncological patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;113(Suppl 1):S14-S16.

73 Wang JX, Yap YY, Matthews CD. Frozen–thawed embryo transfer: Influence of clinical factors on implantation rate and risk of multiple conception. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2316-2319.

74 Son WY, Yoon SH, Yoon HJ, et al. Pregnancy outcome following transfer of human blastocysts vitrified on electron microscopy grids after induced collapse of the blastocoele. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:137-139.

75 Assisted reproductive technology in the United States. 1998 results generated from the American Society for Reproductive Medicine/Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Registry. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:18-31.

76 Meniru GI, Craft I. In vitro fertilization and embryo cryopreservation prior to hysterectomy for cervical cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;56:69-70.

77 Pelinck MJ, Hoek A, Simons AH, et al. Efficacy of natural cycle IVF: A review of the literature. Hum Reprod Update. 2002;8:129-139.

78 Oktay K, Buyuk E, Davis O, et al. Fertility preservation in breast cancer patients: IVF and embryo cryopreservation after ovarian stimulation with tamoxifen. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:90-95.

79 Pena JE, Chang PL, Chan LK, et al. Supraphysiological estradiol levels do not affect oocyte and embryo quality in oocyte donation cycles. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:83-87.

80 Pfister CU, Martoni A, Zamagni C, et al. Effect of age and single versus multiple dose pharmacokinetics of letrozole (Femara) in breast cancer patients. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2001;22:191-197.

81 Mouridsen H, Gershanovich M, Sun Y, et al. Phase III study of letrozole versus tamoxifen as first-line therapy of advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women: Analysis of survival and update of efficacy from the International Letrozole Breast Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2101-2109.

82 Mitwally MF, Casper RF. Aromatase inhibition reduces gonadotrophin dose required for controlled ovarian stimulation in women with unexplained infertility. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1588-1597.

83 Ginsburg ES, Yanushpolsky EH, Jackson KV. In vitro fertilization for cancer patients and survivors. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:705-710.

84 Oktay K, Buyuk E, Akar Z, et al. Fertility preservation in breast cancer patients: A prospective controlled comparison of ovarian stimulation with tamoxifen and letrozole for embryo cryopreservation. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:S1.

85 Oktay K. Further evidence on the safety and success of ovarian stimulation with letrozole and tamoxifen in breast cancer patients undergoing in vitro fertilization to cryopreserve their embryos for fertility preservation. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3858-3859.

86 Oktay K, Buyuk E. The potential of ovarian tissue transplant to preserve fertility. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2002;2:361-370.

87 Mazur P. The role of intracellular freezing in the death of cells cooled at supraoptimal rates. Cryobiology. 1977;14:251-272.

88 Gosden RG, Baird DT, Wade JC, et al. Restoration of fertility to oophorectomized sheep by ovarian autografts stored at −196°C. Hum Reprod. 1994;9:597-603.

89 Baird DT, Webb R, Campbell BK, et al. Long-term ovarian function in sheep after ovariectomy and transplantation of autografts stored at −196°C. Endocrinology. 1999;140:462-471.

90 Oktay K, Buyuk E, Veeck L, et al. Embryo development after heterotopic transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue. Lancet. 2004;363:837-840.

91 Donnez J, Dolmans MM, Demylle D, et al. Livebirth after orthotopic transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue. Lancet. 2004;364:1405-1410.

92 Meirow D, Levron J, Eldar-Geva T, et al. Pregnancy after transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue in a patient with ovarian failure after chemotherapy. NEJM. 2005;353:318-321.

93 Oktay K, Nugent D, Newton H, et al. Isolation and characterization of primordial follicles from fresh and cryopreserved human ovarian tissue. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:481-486.

94 Aubard Y. Ovarian tissue graft: From animal experiment to practice in the human. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;86:1-3.

95 Jeremias E, Bedaiwy MA, Biscotti C, Falcone T. Assessment of injury in cryopreserved ovarian tissue. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:651-653.

96 Jeremias E, Bedaiwy MA, Gurunluoglu R, et al. Heterotopic autotransplantation of the ovary with microvascular anastomosis: A novel surgical technique. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:1278-1282.

97 Bedaiwy MA, Jeremias E, Gurunluoglu R, et al. Restoration of ovarian function after autotransplantation of intact frozen-thawed sheep ovaries with microvascular anastomosis. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:594-602.

98 Gook DA, Edgar DH, Borg J, et al. Oocyte maturation, follicle rupture and luteinization in human cryopreserved ovarian tissue following xenografting. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1772-1781.

99 Agarwal A, Ranganathan P, Kattal N, et al. Fertility after cancer: A prospective review of assisted reproductive outcome with banked semen specimens. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:342-348.

100 Viviani S, Santoro A, Ragni G, et al. Gonadal toxicity after combination chemotherapy for Hodgkin’s disease. Comparative results of MOPP vs. ABVD. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1985;21:601-605.

101 Dubey P, Wilson G, Mathur KK, et al. Recovery of sperm production following radiation therapy for Hodgkin’s disease after induction chemotherapy with mitoxantrone, vincristine, vinblastine, and prednisone (NOVP). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:609-617.

102 Meistrich ML, Wilson G, Mathur K, et al. Rapid recovery of spermatogenesis after mitoxantrone, vincristine, vinblastine, and prednisone chemotherapy for Hodgkin’s disease. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:3488-3495.

103 Marmor D, Duyck F. Male reproductive potential after MOPP therapy for Hodgkin’s disease: A long-term survey. Andrologia. 1995;27:99-106.

104 Shafford EA, Kingston JE, Malpas JS, et al. Testicular function following the treatment of Hodgkin’s disease in childhood. Br J Cancer. 1993;68:1199-1204.

105 Meistrich ML, Wilson G, Brown BW, et al. Impact of cyclophosphamide on long-term reduction in sperm count in men treated with combination chemotherapy for Ewing and soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer. 1992;70:2703-2712.

106 Meistrich M, Shetty G. Suppression of testosterone stimulates recovery of spermatogenesis after cancer treatment. Int J Androl. 2003;26:141-146.

107 Howell SJ, Shalet SM. Effect of cancer therapy on pituitary–testicular axis. Int J Androl. 2002;25:269-276.

108 Shalet S, Tsatsoulis A, Whitehead E, et al. Vulnerability of the human Leydig cell to radiation damage is dependent upon age. J Endocrinol. 1989;120:161-165.

109 Recchia F, Siga G, De Fillipis S, et al. Goserelin as ovarian protection in the adjuvant treatment of premenopausal breast cancer: A phase II pilot study. Anticancer Drugs. 2002;13:417-424.