Chapter 34 Female Infertility

INTRODUCTION

Definitions

Infertility

Infertility is associated with a broad spectrum of definitions and classifications, indicating that it is interpreted very differently by various groups and individuals (Table 34-1). Broadly defined, infertility depicts a diminished capability to conceive and thereby bear children.

| Infertility | One-year period of unprotected intercourse without successful conception |

| Subfertility | An ability to conceive a pregnancy that is decreased from age-matched and population-matched controls |

| Fecundability | The probability that actions taken in a single menstrual cycle will result in a pregnancy |

| Fecundity | The probability that actions taken in a single menstrual cycle will result in a live birth |

| Primary infertility | A patient who has never been pregnant |

| Secondary infertility | A patient with a previous history of a pregnancy regardless of outcome (i.e., spontaneous abortion, ectopic pregnancy, stillbirth, or live birth) |

| Chemical pregnancy | A pregnancy diagnosed by a positive β-hCG titer that spontaneously aborts before clinical verification by other means such as transvaginal ultrasonography |

| Clinical pregnancy | A pregnancy diagnosed by a positive β-hCG titer and clinically verified, usually with transvaginal ultrasound (i.e., intrauterine sac or fetal cardiac activity) or, in cases of miscarriage, by pathologic examination |

The medical definition of infertility is a 1-year period of unprotected intercourse without successful conception. Utilizing this strict interpretation, infertility is a common problem, affecting at least 10% to 15% of all couples. Based on observational data, the remaining 85% to 90% of couples attempting conception will achieve a pregnancy within that 1-year timeframe.1,2

When viewed across the entirety of their reproductive lifetimes, the problem becomes even more common, and up to 25% of women can have an episode of undesired infertility for which they actively seek medical assistance.3 This is because the desire to conceive can change markedly over the reproductive life of a woman, which is generally considered to be between ages 15 and 44. Couples additionally may not actively attempt conception continually during an entire calendar year, but sporadically across a wider timespan.

Normal Fecundity Rates

Overall birth rates in the United States have changed markedly over the past 200 years due to an innumerable set of changes in physical, environmental, and social circumstances. The first official U.S. census was performed in 1790 and reported an overall crude birth rate of 55 per 1000 population.4

To measure the true reproductive capacities of Homo sapiens sapiens as individual biologic beings, studies of fertility in the so-called natural populations should be closely examined. Natural population is a term given to groups in which couples are generally permitted to reproduce without any societal limitation to reproduction.5

The Hutterites of North America are an often utilized example of such a natural population.6–8 This sect of Swiss immigrants originally came to the New World in the mid-sixteenth century and eventually settled in several locations, all in the northern United States and southern Canada. The Hutterites are a closed and very close-knit, truly communal society. There are only six surnames within the entire social structure. All families share equally, and there is therefore no direct impetus or incentive to limit the size of the nuclear family unit. Consequently, they absolutely refuse to use contraception. Overall, the average number of pregnancies per female was 15, while the number of live births averaged 11. Remarkably, although the overall rate of infertility was only 2.4%, a marked decrease in fecundity with advancing age has been documented, with 89% of Hutterite women having their last live birth after age 34, 67% bearing children after age 40, and a mere 13% after age 45. We will discuss the effects of advancing age on fertility later in this chapter.

Data from studies such as these have suggested that fertility in women generally peaks between ages 20 and 24.9,10 It remains fairly stable until approximately age 30 to 32, at which time it begins to decline progressively.11,12 This decline accelerates markedly after age 40. At a bottom line, therefore, fecundity rates in women at age 20 approximate 20% per cycle. This is the peak fecundity rate reflected in the natural setting and can be used as the gold standard when comparing success rates. Subsequently, fertility rates decrease by 4% to 8% in women age 25 to 29; 15% to 19% lower by age 30 to 34; 26% to 46% by age 35 to 39, and 95% lower at age 40 to 45.4,13

Over short periods of time, any cross-sectional population of infertile couples will behave in a relatively uniform manner; in other words, a statistically constant proportion will conceive with each additional cycle of treatment and follow-up. Over longer periods of time however, cycle fecundability appears to decline markedly and the overall cumulative pregnancy rate eventually plateaus.14,15

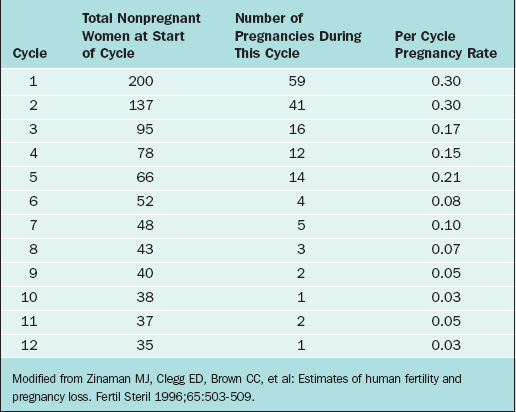

The overall pregnancy rate will never reach 100%. This is primarily due to the overall heterogeneity of infertile and subfertile populations as a whole. Those couples with the highest relative fecundity rates achieve pregnancy most rapidly and are therefore removed from the population, leaving only those couples with more serious problems remaining in the infertile pool. As an example, Zinaman and colleagues reported a prospective observational study of 200 healthy couples desiring to achieve pregnancy and followed them conservatively over a period of 12 menstrual cycles.16

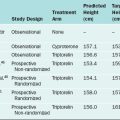

The fecundability rates were highest during the first 2 months of follow-up, greater than 25% per cycle, and had dropped drastically by 6 months to less than 10% per cycle. By the end of the trial, the per cycle fecundability rate was only 3% (Table 34-2).

CAUSES OF INFERTILITY AND SUBFERTILITY

The simplest manner to express the overall causes of medical and environmental conditions that cause infertility is to divide the overall problem into male factors and female factors. One of the broadest investigations concerning these categorizations was conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) Task Force on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Infertility in 1992.17 Although there were several significant differences in their findings depending on the economic environment of the populations studied, the data was remarkably uniform.

The actual percentages that individual factors are found to be the primary cause of infertility vary widely between studies. However, in a broad meta-analysis of more than 20 trials studying infertile couples, the following primary diagnoses were found: disorders of ovulation (27%), abnormal semen parameters (25%), abnormalities of the fallopian tube (22%), unexplained infertility (17%), endometriosis (5%), and other (4%).18 An additional cause is cervical factors, including cervical stenosis, which accounts for up to 5% of infertility in many series.19

Direct observations on human populations allow us to group the causes of infertility into five broad categories, listed in Table 34-3. This broad listing of root causes, although perhaps not complete, can be used as a basis for the initial evaluation of the infertile couple. The overall purpose of the evaluation is to determine which of these overall processes needs to be improved, repaired, or overcome to establish a successful pregnancy. Each question asked at the initial interview, each laboratory test requested, every diagnostic procedure performed must always reflect the need to categorize the problem as simply as possible to suggest the appropriate remedy.

Infertility and Weight

Anovulation, oligo-ovulation, subfertility, and infertility have all been commonly described in women who are significantly above or below their ideal body weight.20

In one study, women with anovulatory infertility were stratified by body mass index (BMI) and compared to normal fertile controls.21 It was clear that the overall risk of ovulatory abnormality was increased with any significant variation from ideal body weight. Obese women (BMI > 27 kg/m2) had a relative risk of anovulatory infertility of 3.1 compared to women closer to their ideal body weight (BMI 20–25 kg/m2). At the same time, women with a BMI lower than 17 kg/m2 had a relative risk of anovulatory infertility of 1.6. Although the relative risk of anovulation was highest in obese women, it was also significantly increased in underweight women as well.

INITIAL EVALUATION OF THE INFERTILE COUPLE

Last, this initial evaluation should lay down the guidelines of possibility to the patients. Not all therapies will work in all patients and not all patients will become pregnant regardless of the therapy. The couple should be given a concise outline of the possibilities of care and all of the information necessary to make an intelligent decision concerning their options. When the patients are allowed to have such an involvement in decision making, it allows them to more easily accept the failure of any individual therapy and helps them reach closure if success is never attained.

Primary Elements of the Initial Infertility Evaluation

The initial evaluation consists of seven primary elements (Table 34-4). It is recommended that the entire initial evaluation should be completed before direct recommendations concerning treatment are suggested to the patients. Most patients will accept a temporary delay in their therapies while full evaluation of all aspects of their clinical state is accomplished far easier than they do frequent changes in their protocol interspersed with intermittent testing and analysis.

| History |

| Physical examination |

| Semen analysis |

| Tests of hormonal status |

| Assessment of tubal patency |

| Tests of ovulatory status |

| Assessment of luteinization |

HISTORY

In the female partner, the relevant medical history concerning the causes and the nature of infertility covers a broad range of subjects.22,23

Attention to detail during this collection of data is imperative.

Demographics

It is important to determine where the patient has lived. Extragenital Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections remain one of the most common causes of pelvic inflammatory disease in the third world.24–26

In areas where tuberculosis is an endemic disease, such as Vietnam and the Philippines, tuberculus epididymitis and salpingitis are common. If recent diagnostic testing has not been done, placement of an intermediate purified protein derivative (iPPD) should be performed and the results drive further investigation. Even in the United States, up to 2% to 5% of tubal disease can be tubercular in nature.27

Menstrual History

Information should be obtained about the following subjects:

Gynecologic History

Gynecologic questioning should include questions about the following subjects:

Obstetric History

Family History

| Ethnic Group | Disorder | Screening Test |

|---|---|---|

| Ashkenazi Jews |

Adapted from American Society for Reproductive Medicine: Appendix A: Minimal genetic screening for gamete donors. In 2004 Compendium of ASRM practice committee and ethics committee reports. Fertil Steril 82:S22–S23, 2004.

Social History

The utilization of herbal preparations in the United States has reached epidemic proportions. As much as 32% of the population as a whole use some type of herbal preparation purchased over the counter,36 but less than 8% will volunteer these substances when asked openly what medications they are taking.37

Many of these products have ingredients that contain active hormones, estrogen disrupters, vasoactive amines, or anti-inflammatory ingredients, all of which can have a marked effect on both the menstrual cycle and fecundity. Not all of these products are contraindicated; their ingredients should be examined by the physician for possible effects on reproduction. There are many on-line (www.pda.com or www.NaturalDatabase.com) and print compendiums that outline the specific nature of the herbal and vitamin ingredients of these over-the-counter supplements.38,39

Sexual History

Coital Frequency and Timing

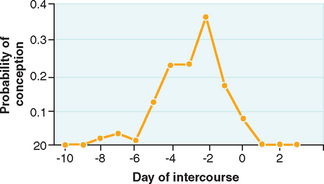

It is important to be aware of the association of coital timing and the probability of successful conception (Fig. 34-1). Because activated sperm can last for up to 80 hours in the female reproductive tract,40,41 it has long been a general recommendation that intercourse occur at specific times during the menstrual cycle to ensure that at the time of expected ovulation there will be capacitated sperm available for fertilization. There can, however, be a significant diminution of both cycle and overall fecundity rates if coitus becomes too frequent.42,43

Dyspareunia

Is there deep thrust dyspareunia? Deep thrust dyspareunia can be a very common gynecologic problem, but it is usually an episodic or intermittent complaint.44

The etiology of this symptom stems from the relative immobility of the pelvic organs and arises from rapid stretching of the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments due to the sudden movement of the cervical/uterine unit during coitus. It can also be caused by direct pressure on nodular lesions of endometriosis in the uterosacral ligaments or in the pouch of Douglas. Deep thrust dyspareunia should raise the suspicion of an organic disease, such as endometriosis or adenomyosis.45–48

Is there increased pain with orgasm? Orgasm is physiologic, typified by rhythmic contractions of the orgasmic platform and the uterus, created involuntarily by localized vasocongestion and myotonia.49 These contractions have a recorded rhythmicity of approximately 0.8 seconds, as the tension increment is released in the orgasmic platform, but accumulates slowly and more irregularly in the uterine corpus. The eventual strength of these uterine contractions may be 4 to 5 times the baseline to peak intensity of a labor contraction.50

Localized production of prostaglandins and endoperoxidases in both endometriosis and adenomyosis can intensify these contractions and cause sensitization of C-afferent nerve fibers in the pelvis, thereby eliciting greater pain with each of these individual contractions.51 Marked pain with orgasm may therefore be a diagnostic suggestion of organic disease of the reproductive tract.52

Sexual Orientation

In the United States alone, an estimated 2.3 million women identify themselves as lesbians.53 Many of these women will present for medical therapy of this absolute male factor infertility, either alone or with a partner. Traditionally, many physicians have altered their history taking and diagnostic regimen in lesbian populations due to the seeming absence of significant risk factors for pelvic inflammatory disease and other sexually transmitted diseases. However, this is not always the case.

Numerous studies have reported that 53% to 99% of women who identify themselves as lesbians have at some time had sex with men, and 25% to 30% of these women continue to have sex with men.54

Up to 25% of this population has been pregnant at one time, and more than 60% of those who had been pregnant report having one or more induced abortions.55

REVIEW OF SYSTEMS

Headaches

Patients should be questioned to find out both the frequency of self-medication with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and the dosage taken. Headaches can be associated with pituitary lesions, such as craniopharyngiomas56,57 and prolactinomas.58,59 Prolactinomas are relatively common causes of anovulation.

Each can cause hormonal derangements that lead to anovulation and infertility. Additionally, frequent headaches of any etiology may lead a patient to self-medicate with large doses of over-the-counter NSAIDs. It has been suggested that at high doses, these medications can interfere with the inflammatory processes of ovulation and implantation.60,61 Patients should also be advised to avoid taking these medications during their therapeutic protocols to prevent these abnormalities.

Visual Changes

The most common presenting feature in space-occupying lesions of the pituitary, such as craniopharyngioma and macroadenomas, is visual impairment (70%).62

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Weight and Body Mass Index

The connection between increased BMI and anovulatory infertility has been discussed in this chapter under Causes of Infertility and Subfertility. Documentation of patient’s vital statistics are generally more comparable across large populations when determined as a BMI rather than a simple listing of absolute body weight and height. For example, 200 pounds is significantly different when compacted into patients of differing heights. Standardized charts for calculation of BMI are available from the ASRM.65

Thyroid Abnormalities

As outlined elsewhere in this text, abnormalities of the thyroid gland can have a marked effect on the menstrual cycle and hence on fecundity. The thyroid gland is one of the largest of the endocrine glands and lies in the anterior neck, immediately below the prominence of the thyroid cartilage. The thyroid is made up of two distinct lobes joined by a thin band of connective tissue called the isthmus. The right lobe of the thyroid is normally significantly more vascular than the left and hence is often the larger of the two lobes.66 Consequently, the right lobe is more often enlarged in disorders associated with a diffuse increase in size.67

The gland itself can be examined in many manners. Many medical students are taught to examine the gland from behind the patient with the tips of the fingers, having the patient swallow to feel the gland in its entirety. It may be less stressful to the patient and more clinically accurate to stand directly in front of her and examine the gland directly with the tips of your dominant hand. In this manner, the tactile sense of the fingertips can be underscored by the visual references of the sternocleidomastoid muscles. It additionally allows the clinician to stand in full view of the patient and decreases the anxiety associated with the examination.

Breast Examination

Asymmetry of the Breasts

It is quite common to have some dyssymmetry in the breasts.68 This should, however, be a developmental finding and not an ongoing and progressive finding. Increasing dyssymmetry in the relative sizes of the breasts may be associated with hyperprolactinemia and organic diseases, such as varicella zoster, that in turn can lead to hyperprolactinemia.69

Galactorrhea

Galactorrhea is the active secretion of breast milk at a physiologically inappropriate time (i.e., a time other than during pregnancy or when the patient is actively breastfeeding a child). Usually white in color, breast milk can be differentiated from a pathologic discharge in several manners. First, secretions that have been hormonally induced usually arise from multiple ductal openings and are commonly found bilaterally. Pathologic discharges, on the other hand, are elicited from single ducts and are primarily unilateral in nature. Second, the discharge can be plated on a slide and examined and stained with Congo Red dye to detect the presence of fat globules.70

Abdomen

The abdomen should be evaluated for evidence of an organic disease that can have a negative effect on fecundity. As an example, the violaceous striae associated with Cushing’s syndrome can be noted on the skin of the abdomen and over the hips.71 Finding these purplish streaks or marked central obesity would thereby suggest an evaluation for hypercortisolemia. Obesity itself should also trigger concern for the effects of BMI on fertility.

Skin

Hirsutism

The overgrowth of terminal hair is succinctly discussed in Chapter 18. Briefly however, there are tremendous differences in the simple connotation of the term an overgrowth of hair. What is deemed abnormal by a patient may not be physiologically abnormal. What is abnormal to one examiner may not be to another. Standardized scoring systems such as the Ferriman-Gallwey72 scale and its modifications73 are useful to quantify the growth of hair. They remain limited by their subjective nature and the wide variability in score assignment and are therefore of little actual clinical use, but they can trigger a recognition of possible hyperandrogenism to help guide the direction of your laboratory examination of the patient.

Tattooing and Body Piercing

These forms of self-expression have become remarkably common over the past decade for both men and women. Once regarded as deviant or markedly rebellious behavior, such body decoration has grown to such popularity that it must now be considered a mainstream expression.74

More than 26% of female college students have a tattoo, and nearly 60% have pierced some part of their bodies.75 The vast popularity of such body decoration has led to an explosion of commercial tattoo and body piercing establishments. Legal regulation unfortunately remains almost completely lacking. Two aspects of this behavior that must be considered in the evaluation of the infertile female.

First, tattooing and body piercing have the potential to cause infection. Most bacterial infections are rarely serious and can be treated with antibiotics, but sexually transmitted diseases, such as syphilis, have been reported.76

Potential viral infections can be far more serious. A direct cause-and-effect relationship has associated these practices with the transmission of blood-borne viral pathogens, including hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), HIV-1, and HIV-2.77–79

The vertical transmission of all of these diseases may have been frequently reported and can have disastrous effects on both the mother and the fetus. Because the fertility evaluation is being performed for the sole purpose of hopefully creating a fetus and hence placing it at risk for the possible vertical transmission of serious infection, any patient with a tattoo or body piercing must be screened appropriately. If the tattoo or body piercing occurred more than 1 year before the examination, convalescent titers for viral infection are sufficient.80 If less than 1 year has elapsed, repetition of such viral screening should be considered at that anniversary.

Second, piercing of the breast, such as the placement of nipple rings, must certainly be considered a substantial stimulation to prolactin secretion. Otherwise healthy-appearing women with regular cyclic menses with nipple rings may induce galactorrhea and clinically significant hyperprolactinemia.81

Discovery of such body jewelry should trigger screening of prolactin secretion. Patients should also be appropriately counseled concerning the potential hormonal effects and be left to decide for themselves about the possible removal of this body adornment.

Gynecologic Examination

Cervix

Abnormalities of the Ectocervix

Malformations of the cervix can include transverse ridges, cervical collars, hoods, coxcombs, pseudopolyps, and cervical hypoplasia and agenesis.82 These uncommon malformations can be idiopathic developmental imperfections or the results of obstetrical trauma and surgery.

Uterus and Adnexa

Uterine Abnormalities

The bimanual examination can often identify uterine abnormalities associated with decreased fecundity, including leiomyomata, adenomyosis, or müllerian anomalies (Table 34-6). Findings such as uterine enlargement, irregularity, or tenderness are often indications for further evaluation.

Table 34-6 Abnormalities that Can be Suspected Based on Bimanual Pelvic Examination

| Uterus |

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

After the completion of a thorough medical history and physical examination, further testing is required and can be subdivided into two categories: (1) preconception screening that should be performed on every woman considering pregnancy and (2) the basic infertility evaluation that will further direct evaluation and treatment. Based on these tests or specific findings in the medical history or the physical examination, it may be necessary to perform more directed and invasive diagnostic procedures as well. An outline of such testing is listed in Table 34-7.

| Tests | |

|---|---|

| Preconception Screening |

Preconception Screening

Papanicolaou Smear

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, (ACOG) recommendations for cervical cytology screening should be followed.83

Blood Type and Screen

Blood typing and determination of Rh factor is required in all female patients considering pregnancy, if not already known.84 In Rh-negative women, antibody testing and appropriate typing of her partner are also recommended to prevent significant alloimmunization in any potential fetus created through these therapies.

Rubella and Varicella Immunity

Determination of a rubella titer is recommended in all patients of childbearing age with no evidence of immunity.85,86 If a woman is found to lack immunity to rubella, she can be immunized on discovery. To date there has been no case of reported congenital rubella syndrome directly attributable to vaccination with the attenuated live virus. Regardless, the current recommendations of the CDC are for a delay of 3 months before conception due to the theoretical risk of the immunization.86

Varicella infection is uncommon in pregnancy, occurring in 0.4 to 0.7 per 1000 patients.87,88 Due to such a low incidence, recommendations for screening for varicella immunity are controversial. Universal screening has been shown not to be cost-effective.89 On the other hand, the CDC considers nonpregnant women of childbearing age as a high-risk group and recommends their vaccination.90

Considering both of these factors, it is reasonable to screen infertile women actively attempting conception who have an uncertain history of past varicella infection and subsequently vaccinate the seronegative among them. As with rubella vaccination, the chance of congenital varicella syndrome from inappropriate vaccination during pregnancy is very low.91 A 3-month delay of conception is also recommended after varicella immunization.

Genetic Screening

The ACOG, the ASRM, and the American College of Medical Genetics recommend that appropriate genetic screening be offered to couples as part of preconception counseling.92–94

Many of these recommendations have been made in very specific populations in which carrier status for autosomal recessive disease is more common. It seems reasonable, however, to broaden this screening to autosomal recessive diseases that have higher incidences in whatever ethnic group you are evaluating. Table 34-5 lists the recommended genetic screens for some of the more common ethnic groups encountered in the United States.

Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Screening of women for sexually transmitted diseases is an important part of the infertility evaluation to detect current infections and determine women at increased risk of having pelvic adhesions related to previous infections, even in women determined to be at low risk based on history and physical examination. If donor gametes or any of the ARTs are being considered, screening of both partners is required.95

The current recommendations of the CDC for screening of pregnant women can be used as a guide to screening the infertile female.96 These recommendations call for screening all pregnant women for syphilis (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL] or the rapid plasma reagent [RPR]), hepatitis B (hepatitis B surface antigen [HbsAg]), and Chlamydia (either RNA- or DNA-based testing). Women at moderate or high risk for sexually transmitted diseases should also be screened for gonorrhea (either culture or DNA-based testing), hepatitis C (hepatitis C antibody) and HIV-1 and 2 (ELISA). Due to the current medicolegal environment, screening for HIV should be done on a voluntary basis after consent has been obtained.

For couples considering the use of donor gametes or use of ART, the ASRM recommends thorough testing of both the man and the woman. Screening tests include those listed, with the addition of cytomegalovirus (CMV) antibody and human T-cell lymphocyte virus (HTLV) types I and II.80,97,98

INFERTILITY EVALUATION

Semen Analysis

Men with persistently abnormal semen analyses should be sent to a urologist with a special interest in infertility for further evaluation. The complete evaluation of the male is covered in Chapter 35.

Tubal and Peritoneal Factors

Ultrasonography

An excellent adjunct to the physical examination is transvaginal ultrasonography (see Chapter 30). Skilled examination can elicit the complete anatomy of the cervix, the endometrium, the myometrium, the fallopian tubes, the ovaries, the adnexae and the pouch of Douglas.99,100

Sonohysterography and Sonohysterosalpingography

Sonohysterosalpingography is a ultrasonographic technique recently developed to evaluate tubal patency by the addition of special media and power Doppler imaging or three-dimensional sonography instrumentation.101,102

Until the accuracy of this procedure can be improved, it remains an experimental procedure.

Hysterosalpingography

HSG is a radiographic evaluation that allows visualization of the inside of the uterus and tubes (see Chapter 29).103 Radiographic contrast dye, either water or oil based, is injected into the uterine cavity through the vagina and cervix. The dye fills the uterine cavity and spills into the abdominal cavity if the fallopian tubes are open.

Although the primary purpose of the hysterosalpingogram is not therapeutic, both oil- and water-soluble media have been shown to increase subsequent pregnancy rates by as much as fourfold.104

Diagnostic Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is an important part of the diagnostic testing for many infertile women (see Chapter 44). It is the only way to accurately diagnose the extent of endometriosis and intraperitoneal adhesions. It is also an accurate way to accurately identify abnormalities of the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries.

Evaluation of Ovulation

Basal Body Temperature Charts

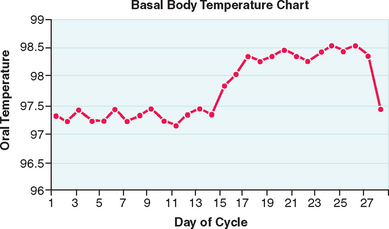

A basal body temperature (BBT) chart, the most traditional method for documenting ovulation, is based on the general effects of progesterone on core basal body temperature. For this test, the woman takes her temperature every morning and plots the results on graph paper. A sustained midcycle rise in temperature indicates that ovulation has probably occurred (Fig. 34-2).

For greatest accuracy, the BBT needs to be a measurement of the basal temperature at rest before arising from bed in the morning.105 A digital thermometer is most commonly used, although an oral thermometer with a scale able to differentiate temperature to tenths of a degree will suffice.

In most ovulatory women, a sustained rise in BBT is indicative of ovulation. This can occur anywhere between 1 to 5 days after the midcycle surge in luteinizing hormone (LH) and up to 4 full days after ovulation has already occurred.106

Classic studies on ovulation prediction and use of the BBT revealed that only 95% of biphasic cycles are ovulatory, and only 80% of monophasic cycles are actually anovulatory.107,108 This indicates a 5% false-positive rate and a 20% false-negative rate.

Serum Progesterone

Another method for documenting that ovulation has occurred is the measurement of serum progesterone levels. With the resolution of the corpus luteum from the previous menstrual cycle, serum progesterone levels remain below 1 ng/mL during most of the follicular phase. They rise during the late follicular phase to 1 to 2 ng/mL, an increase partially responsible for the change in pituitary sensitivity to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) that creates the midcycle LH surge.109

After ovulation, progesterone levels rise steadily until they peak 7 to 8 days after ovulation. Any level of serum progesterone greater than 3 ng/mL provides reliable evidence that luteinization of the follicle, and hence ovulation, has occurred.110

There are several ways to determine the appropriate time to measure midluteal progesterone levels. In the past, serum progesterone level was measured on day 21 of the menstrual cycle, based on the classic 28-day menstrual cycle.111

Probably the best way to time measurement of midluteal progesterone is with the use of a urinary LH kit. Assuming that ovulation will occur within 24 to 36 hours of the beginning of the LH surge detected in the urine, midluteal serum progesterone can best be measured 7 to 8 hours after detection of the surge.

Although measurement of serum progesterone levels can be used as a documentation of ovulation and an adequate luteal phase, like the BBT, this test cannot be used to prospectively predict when ovulation will occur. Another concern is that, in some women, luteinization and progesterone production might occur without the actual release of the oocyte, a condition known as luteinized unruptured follicle syndrome.112,113 Many clinicians do not believe that this condition occurs often enough to be of clinical concern.

Urinary LH Measurements

Due to many factors, women in the northern hemisphere generally start their LH surge early in the morning. Because it takes several hours for LH to subsequently appear in the urine, the best results correlate with testing done in the late afternoon or early evening (1600 to 2200 hours).114,115

Testing twice a day will greatly decrease false-negative results but is not really necessary if testing is done regularly and at a standardized time. Ovulation will generally follow an afternoon or early evening urinary detection of LH within 14 to 26 hours.116 Consequently, if these tests are being used to time coitus or an IUI, the day after the first positive test will have the highest success rate.117

Although the accuracy of many of these ovulation predictor kits can vary, the most accurate kits predict ovulation within the next 24 to 48 hours with 90% accuracy.116,118,119

Endometrial Biopsy

The endometrial biopsy is no longer recommended as part of the standard infertility evaluation. In the past, the endometrial biopsy was used as a test of luteinization and ovulation based on the known effects of progesterone secretion on the endometrium, much like a luteal phase serum progesterone level.120

Although painful and costly, this office test was once considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of luteal phase deficiency.111 However, a large multicenter study showed convincingly that out-of-phase biopsy does not discriminate between fertile and infertile women.121 Although not a standard part of the modern infertility evaluation, the endometrial biopsy remains a vital research technique in the study of the ultrastructure of the endometrium and its receptivity to embryonic implantation.

Evaluating Hormonal Causes of Ovulation Dysfunction

Thyrotropin

Hypothyroidism, a relatively common problem in women, can present as ovulation dysfunction with few other symptoms. The simplest screening test for hypothyroidism is the measurement of thyrotropin. It is reflective of all feedback to the central nervous system and is an excellent direct measure of thyroid health. Consequently, a thyrotropin level should be drawn at the initial evaluation. When the thyrotropin is elevated, this is suggestive of hypothyroidism and should be followed with measurement of free T4 or free thyroxine index.122

Prolactin

Hyperprolactinemia can cause menstrual disruption, oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea, and consequently infertility.123,124 Hyperprolactinemia is another relatively common clinical entity and can be caused by a myriad of pathologic processes. Prolactin-secreting adenomas are the most common pituitary tumor in women.125

There has been some concern in the past that prolactin evaluation after a breast examination might lead to spurious elevation since breast or nipple stimulation can markedly increase serum prolactin levels during pregnancy.126 In some patients, breast augmentation can increase serum prolactin concentrations.127

However, in the nonpregnant patient, routine breast examination does not acutely alter serum prolactin levels.128 Consequently, prolactin measurements can be drawn immediately after the initial infertility evaluation with little fear of spurious elevation.

It should also be remembered that thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) is a potent prolactin-stimulating substance.129 Because TRH as well as thyrotropin is elevated in hypothyroid states, prolactin secretion will also be elevated in such circumstances. To avoid confusion, thyrotropin and prolactin levels should be drawn together and under the specifications outlined here.

Cervical Factor

Cervical factor accounts for approximately 5% of all clinical referrals for infertility.19 This is not surprising because the narrow cervix is the site where the greatest reduction in the number of sperm allowed to progress further into the female reproductive tract occurs. Of the 40 to 100 million sperm contained in an average ejaculate, only a small percentage manages to enter the uterus and proceed to the point of fertilization in the tubal ampulla. The ability of adequate number of sperm to traverse the cervix is dependent on both the diameter of the cervical os and the quantity and quality of the cervical mucus.

Postcoital Test

Perhaps one of the oldest diagnostic tests for infertility is the postcoital test, first described by J. Marion Simms in 1866.130 This test for cervical factor infertility evaluates the amount and quality of cervical mucus and is usually performed 2 to 12 hours after coitus immediately before ovulation. Appropriate timing is assumed to be 24 hours after the urinary detection of an LH surge or 24 hours after intramuscular administration of human chorionic gonadotropin to induce ovulation. Performing the postcoital test either too early or too late can result in spuriously poor results.

The postcoital test is no longer considered to be an important part of the infertility evaluation. One reason is that the sperm count is the only factor evaluated with a postcoital test that has been found to be predictive of pregnancy.130,131

Another reason for the fall from favor of the postcoital test is that the results rarely alter treatment decisions. If the postcoital test is repeatedly abnormal, the patient is treated with IUI, the most effective treatment for cervical factor fertility. If the postcoital test is normal, most patients are still treated with IUI, because it is also an effective treatment for unexplained infertility and improves pregnancy rates over other forms of insemination regardless of the cause of infertility.132

Androgen Excess

The signs and symptoms of hyperandrogenism can be elicited during the initial history and physical examination. When androgen excess is suspected, the patient should be screened to exclude ovarian or adrenal tumors by measuring serum androgens. Although both of these organs produce a range of androgens, tumors should be suspected if there is a de novo or rapid evolution of clinical hyperandrogenism rather than by any particular serum androgen level. Imaging studies for androgen tumors include transvaginal ultrasonography and computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the adrenals. Elevated serum testosterone or dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate is often due to polycystic ovary syndrome (see Chapter 15).

Some clinicians suggest that free testosterone might be a better diagnostic measurement of hyperandrogenicity than total testosterone.133 This is because the overwhelming majority of testosterone is bound to either sex-hormone binding globulin or albumin, and the androgenic effects of testosterone are created solely by the remaining 1% free testosterone. Measuring free testosterone is not necessary because there is an excellent direct correlation between total and free testosterone levels.134 Patients with elevated total testosterone will uniformly have elevated free testosterone as well.

Nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia should be considered in women with hyperandrogenism and a significant family history of subfertility or infertility. In non-Jewish white populations, 1% to 5% of hyperandrogenic women are deficient in the activity of adrenal enzymes necessary to produce cortisol, most commonly 21-hydroxylase.135 The disorder is genetic and transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait. The best screening test for nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia remains measurement of 17OH-progesterone.136

The Evaluation of Ovarian Reserve

Day 3 FSH

As the quality of the remaining oocyte pool decreases, the amount of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) secreted by the pituitary can be expected to progressively increase to drive the failing ovary harder. An early follicular, or basal, FSH drawn on cycle day 3 can have predictive value on the possibility of fertility.137–139 When basal FSH levels are elevated, especially above 10 to 15 IU/L, success with even the most provocative therapies, including in vitro fertilization, is greatly diminished.140

Clomiphene Citrate Challenge Test

The clomiphene citrate challenge test (CCCT) is a provocative examination of endocrine dynamics that is an even more sensitive test of ovarian reserve than basal FSH measurements.141 In this test a basal FSH level is measured on day 3 of the cycle. The patient is then given clomiphene citrate, 100 mg daily on days 5 to 9. The FSH level is again measured on cycle day 10. This test is considered abnormal if either day 3 or day 10 FSH levels are greater than 10 to 15 IU/L, depending on the laboratory.

The CCCT is based on the two negative feedback mechanisms for the secretion of FSH from the ovary to the central nervous system: estrogen and inhibin B. When clomiphene citrate is given to women younger than age 35, it generally induces a transient increase in gonadotropin levels, with LH rising relatively more than FSH. This is due to the inhibitory effect of the large amount of inhibin B secreted by the granulosa cells of the developing follicles.142

When clomiphene citrate is given to a woman older than age 35 or one with diminishing ovarian reserve, the smaller follicular cohort results in significantly less feedback inhibition on FSH secretion.143 In this case elevations of either the basal and/or stimulated FSH levels are indicative of poor reproductive prognosis. Even with a normal basal FSH, a patient with an abnormally high day 10 value has a poorer prognosis.

TREATMENT

Emotional Needs

To meet the emotional needs of patients, it is important to acknowledge infertility as a medical and emotional struggle with a wide variety of stressors, including physical, financial, social, and marital.144 It is also important for clinicians and staff to be both sensitive and supportive to the couple. The importance and value of both members of the couple in the family and their involvement in treatment cannot be overemphasized. If there is evidence of significant emotional distress, the physician should be ready to offer help in terms of support groups or a professional infertility counselor.

In addition to local resources, there are many national support organizations that can assist couples in satisfying their emotional needs, including RESOLVE (www.resolve.org), the American Fertility Association (www.theafa.org), and the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM)(www.asrm.org).

SUMMARY

1 Mosher WD, Pratt WF. Fecundity and infertility in the United States: Incidence and trends. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:192-193.

2 Greenhall E, Vessey M. The prevalence of subfertility: A review of the current confusion and a report of two new studies. Fertil Steril. 1990;54:978-983.

3 Mosher W, Pratt W. Fecundity and Infertility in the United States, 1965–1988. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics, No. 192. Hyattsville, Md.: National Center for Health Statistics, Dec. 4, 1990.

4 Ventura SJ, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD. Revised birth and fertility rates for the United States, 2000 and 2001. Nat Vital Stat Rep. 2003;51:1-17.

5 Menken J, Trussell J, Larsen U. Age and infertility. Science. 1986;233:1389-1394.

6 Tietze C. Reproductive span and rate of reproduction among Hutterite women. Fertil Steril. 1957;8:89-97.

7 White KJ. Declining fertility among North American Hutterites: The use of birth control within a Dariusleut colony. Soc Biol. 2002;49:58-73.

8 Arcos-Burgos M, Muenke M. Genetics of population isolates. Clin Genet. 2002;61:233-247.

9 Maroulis GB. Effect of aging on fertility and pregnancy. Semin Reprod Endocrinol. 1991;9:165-179.

10 Treolar AE. Menarche, menopause and intervening fecundability. Hum Biol. 1974;46:89-107.

11 Henry L. Some data on natural fertility. Eugenics Q. 1961;8:81-91.

12 Stein ZA. A women’s age: Childbearing and childrearing. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:327-342.

13 Mosher AD. Infertility trends among US couples: 1965–1976. Fam Plann Persp. 1982;14:22-26.

14 Cramer DW, Walker AM, Schiff I. Statistical methods in evaluating the outcome of infertility therapy. Fertil Steril. 1979;32:80-86.

15 Guttmacher AF. Factors effecting normal expectancy of conception. JAMA. 1956;161:855-860.

16 Zinaman MJ, Clegg ED, Brown CC, et al. Estimates of human fertility and pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:503-509.

17 WHO Scientific Group Report. Recent Advances in Medically Assisted Conception. WHO Technical Report Series 820. Geneva: WHO, 1992.

18 Collins JA. Unexplained infertility. In: Keye WR, Chang RJ, Rebar RW, Soules MR, editors. Infertility: Evaluation and Treatment. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995:249-262.

19 Sills ES, Palermo GD. Intrauterine pregnancy following low-dose gonadotropin ovulation induction and direct intraperitoneal insemination for severe cervical stenosis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2002;2:9.

20 Frisch RE. The right weight: Body fat, menarche and ovulation. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1990;4:419-439.

21 Grodstein F, Goldman MD, Cramer DW. Body mass index and ovulatory infertility. Epidemiology. 1994;5:247-250.

22 American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Optimal evaluation of the infertile female. A practice committee report. Birmingham, Ala.: ASRM, 2000.

23 Evers JL. Female subfertility. Lancet. 2002;360:151-159.

24 Myers JA. The natural history of tuberculosis in the human body. III. Tuberculous women and their children. Am Rev Resp Dis. 1961;84:558.

25 Cates W, Rolfs RT, Aral SO. Sexually transmitted diseases, pelvic inflammatory disease, and infertility: An epidemiologic update. Epidemiol Rev. 1990;12:199-220.

26 Wølner-Hanssen P, Kiviat NK, Holmes KK. Atypical pelvic inflammatory disease: Subacute, chronic or subclinical upper genital tract infection in women. In: Holmes KK, Mardh P-A, Sparling PF, Weisner PJ, editors. Sexually Transmitted Disease. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1990:615-620.

27 Daly JW, Monif GRG. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Harper & Row; 1986:303.

28 Donnez J, Nisolle M, Smoes P, et al. Peritoneal endometriosis and “endometriotic” nodules of the rectovaginal septum are two different entities. Fertil Steril. 1996;66:362-368.

29 Vercellini P. Endometriosis: What a pain it is. Sem Reprod Endocrinol. 1997;15:251-261.

30 Schiffer MA, Elguezabal A, Sultana M, Allen AC. Actinomycosis infections associated with intrauterine contraceptive devices. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;45:67-72.

31 Lomax CW, Harbert GM, Thornton WN. Actinomycosis of the female genital tract. Obstet Gynecol. 1976;48:341-346.

32 Cunningham FG, Gant NF, Leveno KJ, et al (eds). Williams Obstetrics, 22nd ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, pp 451–468.

33 Roth L, Taylor HS. Risks of smoking to reproductive health: Assessment of women’s knowledge. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:934-939.

34 Stillman RJ, editor. Seminars in Reproductive Endocrinology: Smoking and Reproductive Health. New York: Thieme, 1989.

35 Laurent SL, Thompson SJ, Addy C, et al. An epidemiologic study of smoking and primary infertility in women. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:565-572.

36 Kaye AD, Clarke AC, Sabar R, et al. Herbal medications: Current trends in anesthesiology practice—a hospital survey. J Clin Anesth. 2000;12:468-471.

37 Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286:208-216.

38 2005 Physicians Desk Reference for Herbal Supplements. Montvale N.J.: Medical Economics, 2005.

39 Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database, 4th ed. Stockton, Calif.: Therapeutic Research Faculty, 2004.

40 Williams M, Hill CJ, Scudamore I, et al. Sperm numbers and distribution within the human fallopian tube around ovulation. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:2019-2026.

41 Gould JE, Overstreet JW, Hanson FW. Assessment of human sperm function after recovery from the female reproductive tract. Biol Reprod. 1984;31:888-894.

42 MacLeod AL, Gold RZ. The male factor in fertility VI: Semen quality and certain other factors in relation to ease of conception. Fertil Steril. 1953;4:10-33.

43 Rantala TA. Coital frequency and long-term fecundity rates. Int J Fertil. 1989;33:26-32.

44 Glatt AE, Zinner SH, McCormack WM. The prevalence of dyspareunia. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:433-436.

45 Adamson GD. Diagnosis and clinical presentation of endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:568-569.

46 Brosens IA, Brosens JJ. Redefining endometriosis: Is deep endometriosis a progressive disease? Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1-3.

47 Nishida M. Relationship between the onset of dysmenorrhea and histologic findings in adenomyosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:229-231.

48 Reinhold C, Atri M, Mehio A, et al. Diffuse uterine adenomyosis: Morphologic criteria and diagnostic accuracy of endovaginal sonograph. Radiology. 1995;197:609-614.

49 Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Response. Boston: Little, Brown, 1966;129.

50 Sarrel P. Sexual physiology and sexual functioning. Postgrad Med. 1975;1:69-72.

51 Garcia-Velasco JA, Arici A. Chemokines and human reproduction. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:983-993.

52 Darrow SL, Selman S, Batt RE, et al. Sexual activity, contraception and reproductive factors in predicting endometriosis. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:500-509.

53 Lesbian health. Current assessment and directions for the future. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Medicine, 1999.

54 Diamant AL, Schuster MA, McGuigan K, Lever J. Lesbians’ sexual history with men: Implications for taking a sexual history. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2730-2736.

55 Marrazzo JM, Stine K. Reproductive health history of lesbians: Implications for care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1298-1304.

56 Banna M. Craniopharyngioma: Based on 160 cases. Br J Radiol. 1976;49:206-223.

57 Sklar CA. Craniopharyngioma: Endocrine abnormalities at presentation. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21:18-20.

58 Schlechte J, Sherman B, Halmi N, et al. Prolactin-secreting pituitary tumors. Endocr Rev. 1980;1:295-308.

59 Vallette-Kasic S, Morange-Ramus I, Selim A, et al. Macroprolactinemia revisited: A study on 106 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:581-588.

60 Smith G, Roberts R, Hall C, Nuki G. Reversible ovulatory failure associated with the development of luteinized unruptured follicles in women with inflammatory arthritis taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:458-462.

61 Zanagnolo V, Dharmarajan AM, Endo K, Wallach EE. Effects of acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) and naproxen sodium (naproxen) on ovulation, prostaglandin, and progesterone production in the rabbit. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:1036-1043.

62 Freda PU, Wardlaw SL, Post KD. Unusual causes of sellar/parasellar masses in a large transsphenoidal surgical series. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3455.

63 Hurley D, Gharib H. Detection and treatment of hypothyroidism and Grave’s disease. Geriatrics. 1995;60:41-44.

64 Krassas GE, Pontikides N, Kaltsas T, et al. Menstrual disturbances in thyrotoxicosis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1994;40:641-644.

65 American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Patient’s Fact Sheet: Weight and Infertility. Birmingham, Ala.: ASRM, 2001.

66 Larsen PR, Ingmar SH. The thyroid gland. In: Wilson JD, Foster DW, editors. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 8th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1992:359.

67 Burrow GN, Oppenheimer JH, Volpe B. Thyroid Function and Disease. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1990.

68 Drukker BH. Examination of the breast by the patient and by the physician. In: Hindle W, editor. Breast Disease for Gynecologists. New York: Appleton & Lange; 1990:52-54.

69 Drukker BH. The diagnosis and management of breast disease. In: Sciarra JJ, editor. Gynecology and Obstetrics. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1999:3-4.

70 Leung AK, Pacaud D. Diagnosis and management of galactorrhea. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:543-550.

71 Miller JW, Crapo L. The medical treatment of Cushing’s disease. Endocr Rev. 1993;14:443.

72 Ferriman D, Gallwey JD. Clinical assessment of body hair in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1961;24:1440.

73 Hatch R, Rosenfeld RL, Kim MH, Tredway D. Hirsutism: Implications and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;140:815.

74 Bryant AS, Chen KT, Camann WR, Norwitz ER. Coping with the complications of tattooing and body piercing. Contemp Obstet/Gynecol. 2005;50:40-47.

75 Mayers LB, Judelson DA, Moriarty BW, et al. Prevalence of body art (body piercing and tattooing) in university undergraduates and incidence of medical complications. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:29-34.

76 Metts J. Common complications of body piercing. Lancet. 2003;361:1205-1215.

77 Mele A, Corono R, Tosti ME, et al. Beauty treatments and risk of parenterally transmitted hepatitis: Results from the hepatitis surveillance system in Italy. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;27:441-444.

78 Pugpatch D, Mileno M, Rich JD. Possible transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from body piercing. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:767-768.

79 Holsen DS, Hartung S, Mymel H. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis C and association with intravenous drug abuse and tattooing in a national prison in Norway. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:673-676.

80 American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Guidelines for oocyte donation. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:S13-S15.

81 Modest GA, Fangman JJ. Nipple piercing and hyperprolactinemia. NEJM. 2002;347:1626-1627.

82 Herbst AL, Bern HA, editors. Developmental effects of diethylstilbesterol (DES) in pregnancy. New York: Thieme-Stratton, 1981.

83 American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Cervical cytology screening. ACOG Technology Assessment Number 2, December 2002. In: ACOG: Compendium of Selected Publications. Washington, D.C.: ACOG; 2005.

84 American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Prevention of Rh D alloimmunization. ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 4, May 1999. In: ACOG: Compendium of Selected Publications. Washington, D.C.: ACOG; 2005.

85 American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Primary and preventative care: Periodic assessments. Committee Opinion Number 292, November 2003. In: ACOG: Compendium of Selected Publications. Washington, D.C.: ACOG; 2005.

86 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Control and prevention of rubella: Evaluation and management of suspected outbreaks, rubella in pregnant women, and surveillance for congenital rubella syndrome. MMWR. 2001;50:1-25.

87 Enders G. Serodiagnosis of varicella-zoster virus infection in pregnancy and standardization of the ELISA IgG and IgM antibody tests. Dev Biol Stand. 1982;52:221-236.

88 Harger JH, Ernest JM, Thurnan GR, et al. Frequency of congenital varicella syndrome in a prospective cohort of 347 pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:260-265.

89 Glantz JC, Mushlin AL. Cost-effectiveness of routine antenatal varicella screening. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:519-528.

90 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of varicella: Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR. 1999;48:1-23.

91 Shields KE, Galil K, Seward J, et al. Varicella vaccine exposure during pregnancy: Data from the first 5 years of the pregnancy registry. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:14-19.

92 American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Prenatal and preconceptual carrier screening for genetic diseases in individuals of eastern European Jewish descent. Committee Opinion Number 298, August 2004. In: ACOG: Compendium of Selected Publications. Washington, D.C.: ACOG; 2005.

93 American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Appendix A: Minimal genetic screening for gamete donors. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:S22-S23.

94 American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Preconception and Prenatal Carrier Screening for Cystic Fibrosis. Washington, D.C.: ACOG, 2001.

95 American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Optimal evaluation of the infertile female. A Practice Committee Report. Birmingham, Ala.: ASRM, 2000.

96 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2002. MMWR. 2002;51:1-36.

97 American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Guidelines for sperm donation. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:S9-S12.

98 American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Guidelines for cryopreserved embryo donation. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:S16-S17.

99 Fleischer AC. Sonography in Gynecology & Obstetrics: Just the Facts. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

100 Timor-Tritsch IE, Rottem S, editors. Transvaginal Sonography, 2nd ed., New York: Elsevier, 1991.

101 Tanawattanacharnan S, Suwajanakorn S, Uepairojkit B, et al. Transvaginal hysterosalpino-contrast sonography (HyCoSy) compared with chromolaparoscopy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2000;26:71-75.

102 Sladkevicius P, Ojha K, Campbell S, Nargund G. Three-dimensional power Doppler imaging in the assessment of fallopian tube patency. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16:644-647.

103 Hurd WW, Wyckoff ET, Reynolds DB, et al. Patient rotation and resolution of unilateral cornual obstruction during hysterosalpingography. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:1275-1278.

104 Spring DB, Barkan HE, Pruyn SC. Potential therapeutic effects of contrast materials in hysterosalpingography: A prospective randomized clinical trial. Kaiser Permanente Infertility Work Group. Radiol. 2000;214:53-57.

105 Bates GW, Garza DE, Garza MM. Clinical manifestations of hormonal changes in the menstrual cycle. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1990;17:299-310.

106 Luciano AA, Peluso J, Koch EI, et al. Temporal relationship and reliability of the clinical, hormonal and ultrasonographic indices of ovulation in infertile women. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:412-416.

107 Moghissi KS. Accuracy of basal body temperature for ovulation induction. Fertil Steril. 1976;27:1415-1421.

108 Moghissi KS. Prediction and detection of ovulation. Fertil Steril. 1980;34:89-98.

109 Investigators World Health Organization Task Force. Temporal relationships between ovulation and defined changes in the concentration of plasma estradiol-17β, luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone and progesterone. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;138:383-390.

110 Wathen NC, Perry L, Lilford RJ, Chard T. Interpretation of single progesterone measurement in diagnosis of anovulation and defective luteal phase: Observations on analysis of the normal range. BMJ. 1984;288:7-9.

111 Noyes RW, Hertig AT, Rock J. Dating the endometrium. Fertil Steril. 1950;1:3-25.

112 Petsos P, Chandler C, Oak M, et al. The assessment of ovulation by a combination of ultrasound and detailed serial hormone profiles in 35 women with long-standing unexplained infertility. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1985;22:739-751.

113 Daly DC, Soto-Albors C, Walters C, et al. Ultrasonographic assessment of luteinized unruptured follicle syndrome in unexplained infertility. Fertil Steril. 1985;43:62-65.

114 Miller PR, Soules MR. The usefulness of a urinary LH kit for ovulation prediction during cycles of normal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:13-17.

115 Lang-Dunlop A, Schultz R, Frank E. Interpretation of the BBT chart using the “Gap” technique compared to the colorline technique. Contraception. 2005;71:188-192.

116 Miller PB, Soules MR. The usefulness of a urinary LH kit for ovulation prediction during menstrual cycles of normal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:13-17.

117 Martinez AR, Bernardus RE, Vermeiden JP, Schoemaker J. Time schedules of intrauterine insemination after urinary luteinizing hormone surge detection and pregnancy results. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1994;8:1-5.

118 Nielsen MS, Barton SD, Hatasaka HH, Stanford JB. Comparison of several one-step home urinary hormone detection kits to OvuQuick. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:384-387.

119 Lloyd R, Coulam CB. The accuracy of urinary luteinizing hormone testing in predicting ovulation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:1370-1372.

120 Wentz AC. Endometrial biopsy in the evaluation of infertility. Fertil Steril. 1980;33:121-124.

121 Coutifaris C, Myers ER, Guzick DS, et alfor the NICHD National Cooperative Reproductive Medicine Network. Histological dating of timed endometrial biopsy tissue is not related to fertility status. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:1264-1272.

122 Spencer C, Eigen A, Shen D, et al. Specificity of sensitive assays of thyrotropin (TSH) used to screen for thyroid disease in hospitalized patients. Clin Chem. 1987;33:1391-1396.

123 Bohnet HG, Dahlen HG, Wutke W, Schneider HPG. Hyperprolactinemic anovulatory syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1976;42:132-143.

124 Moult PJA, Rees LH, Besser GM. Pulsatile gonadotropin secretion in hyperprolactinemic amenorrhoea and the response to bromocriptine therapy. Clin Endocrinol. 1982;16:153-162.

125 Yen SSC, Jaffe RB. Prolactin in human reproduction. In: Yen SSC, Jaffe RB, Barbieri RL, editors. Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology and Clinical Management. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1999:273-274.

126 Hatjis CG, Morris M, Rose JC, et al. Oxytocin, vasopressin and prolactin responses associated with nipple stimulation. South Med J. 1989;82:193-196.

127 Hartmann BW, Laml T, Kirchengast S, et al. Hormonal breast augmentation: Prognostic relevance of insulin-like growth factor-I. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1998;12:123-127.

128 Hammond KR, Steinkampf MP, Boots LR, Blackwell RE. The effect of routine breast examination on serum prolactin levels. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:869-870.

129 Jacobs LS, Snyder PJ, Wilbur JF, et al. Increased serum prolactin after administration of synthetic thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH) in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1971;33:966.

130 Glatstein IZ, Best CL, Palumbo A, et al. The reproducibility of the postcoital test: A prospective study. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:396-400.

131 Beltsos AN, Fisher S, Uhler ML, et al. The relationship of the postcoital test and semen characteristics to pregnancy rates in 200 presumed fertile couples. Int J Fertil Menopausal Stud. 1996;41:405-411.

132 Hurd WW, Randolph JF, Ansbacher R, et al. Comparison of intracervical, intrauterine, and intratubal techniques for donor insemination. Fertil Steril. 1993;59:339-342.

133 Loric S, Guechot J, Duron F, et al. Determination of testosterone in serum not bound by sex-hormone binding globulin: Diagnostic value in hirsute women. Clin Chem. 1988;34:1826-1829.

134 Schwartz U, Moltz L, Brotherton J, Hammerstein J. The diagnostic value of plasma free testosterone in non-tumorous and tumorous hyperandrogenism. Fertil Steril. 1983;40:66-72.

135 Azziz R, Dewailly D, Owerbach D. Clinical review 56: Non-classic adrenal hyperplasia: Current concepts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78:810-815.

136 American Society for Reproductive Medicine. The evaluation and treatment of androgen excess. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:S173-S180.

137 Scott RT, Toner JP, Mujasher SJ, et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone levels on cycle day 3 are predictive of in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril. 1989;51:651-654.

138 Toner JP, Philput CB, Jones GS, Muasher SJ. Basal follicle-stimulating hormone is a better predictor of in vitro fertilization performance than age. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:784-791.

139 Pearlstone AC, Fournet N, Gambone JC, et al. Ovulation induction in women over 40 and older: The importance of basal follicle-stimulating hormone level and chronological age. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:674-679.

140 Scott RT, Hofmann GE. Prognostic assessment of ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril. 1995;63:1-11.

141 Navot D, Rosenwaks Z, Margolioth EJ. Prognostic assessment of female fecundity. Lancet. 1987;ii:645-647.

142 Hofmann GE, Danforth DR, Seifer DB. Inhibin-B: The physiologic basis of the clomiphene citrate challenge test for ovarian reserve screening. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:474-477.

143 Yong PY, Baird DT, Thong KJ, et al. Prospective analysis of the relationships between the ovarian follicle cohort and basal FSH concentration, the inhibin response to exogenous FSH and ovarian follicle number at different stages of the normal menstrual cycle and after pituitary down-regulation. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:35-44.

144 Burns LH, Covington SN. When Infertility Strikes The Family: Helping The System Cope. Available at http://www.resolve.org/main/national/familyfriend/strik.jsp. Accessed