Inflammation, infection and non-neoplastic disease221

21.2 Dysplasia and neoplasia223

The female genital tract comprises the vulva, vagina, uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes and ovaries. Infections in this region are common. Many are relatively trivial, but pelvic inflammatory disease can cause infertility or serious intra-abdominal sepsis. Infection with certain subtypes of human papilloma virus (HPV) predisposes to dysplasia and malignancy in the cervix. Carcinoma of the ovary is the fifth most frequent cause of female cancer mortality in the UK, and often presents at an advanced state. In contrast, the cervical cytology screening programme has allowed early diagnosis of premalignant and invasive cervical carcinomas in many cases, with a consequential fall in mortality from cervical cancer of approximately 40%. Disorders relating specifically to reproductive function include endometriosis, ectopic pregnancy and hydatidiform mole.

21.1. Inflammation, infection and non-neoplastic disease

Genital tract infection

Common causes include:

• bacteria – Gardnerella, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia

• viruses – HPV, herpes simplex type 2

• fungi – Candida albicans

• protozoa – Trichomonas vaginalis.

Gardnerella

Gardnerella is a common cause of vaginitis.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

N. gonorrhoeae can infect the cervix, endometrium, fallopian tubes and ovaries.

Chlamydia trachomatis

C. trachomatis is an intracellular pathogen that causes urethritis, cervicitis and lymphogranuloma venereum (genital ulceration with suppurative and granulomatous inflammation of pelvic, inguinal and rectal lymph nodes). Transmission to neonates during vaginal delivery can cause conjunctivitis and pneumonia.

Staphylococcus

Toxic shock syndrome is a rare but serious infection caused by exotoxins produced by Staphylococcus aureus. It is associated with tampon use and presents with fever, diarrhoea and vomiting, rash and shock. Occasionally it can be fatal.

Human papilloma virus

This infects squamous epithelia at many body sites (see Table 37). Low-risk subtypes cause genital warts (condylomata acuminata); high-risk subtypes are associated with the development of cervical carcinoma. HPV changes are frequently seen in association with cervical dysplasia on tissue biopsy. HPV serotyping using the polymerase chain reaction is likely to play an important part in future cervical cancer screening programmes. Cytological features associated with HPV infection include irregular enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei surrounded by poorly staining cytoplasm (these features are known as koilocytosis), multinucleation and abnormal keratinisation.

| HPV subtype | Associated lesions |

|---|---|

| 1, 2, 4, 7 | Benign squamous cell papillomas (viral warts) |

| 5, 8 | Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma |

| 6, 11 | Benign anogenital warts (condylomata acuminatum) |

| 16, 18 | High-grade cervical epithelial dysplasia |

| (31, 33, 35) | (CIN) and squamous carcinoma |

Herpes simplex type 2

Infection is relatively common in young women. Ulcerating vesicles develop on the vulva, vagina or cervix several days after sexual contact. Spontaneous healing occurs but latent infection leads to recurrent attacks. Neonatal transmission during vaginal delivery can cause severe systemic infection and neonatal death. Herpes simplex 2 is also associated with cervical carcinogenesis.

Trichomonas vaginalis

Trichomatosis is a sexually transmitted infection and causes a foamy discharge, itching, dysuria and dyspareunia. Trichomonas, Candida and herpes virus infections may be identified incidentally on cytological examination of routine cervical screening smears (see below).

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) describes a chronic upper genital tract infection that presents as pelvic pain, fever and vaginal discharge. Causative organisms include gonococci and Chlamydia, although other bacteria can cause PID following termination of pregnancy or spontaneous vaginal delivery. Actinomycosis is a common infection in users of contraceptive coils. Infection spreads from the lower genital tract to the fallopian tubes and ovaries. Complications include tubo-ovarian abscess, pyosalpinx, peritonitis, intestinal obstruction and infertility.

Chronic endometritis

Chronic endometritis is identified microscopically by the presence of plasma cells in the endometrium. Chronic endometrial infection occurs:

• in association with intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUD, ‘coil’)

• in patients with chronic PID

• in association with retained products of pregnancy

• in tuberculosis – diagnosis can be difficult as cyclical endometrial shedding prevents the formation of typical caseating granulomas

• without other associated factors (15%).

Treatment depends on the underlying cause – antibiotics, removal or replacement of the IUD or endometrial curettage to remove retained gestational tissue.

Lichen sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus a chronic inflammatory skin condition that most commonly affects the vulva. Classically, the surface keratin is thickened, the epidermis is atrophic and the dermis is abnormally fibrotic. There is an increased risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma.

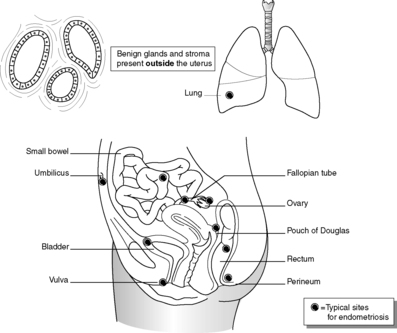

Endometriosis

Endometriosis a common condition in which endometrial glands and stroma are present in organs other than the uterus (Box 28 and Figure 57). Typical sites of endometriosis include the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterosacral ligaments, Pouch of Douglas and cervix, but it can occur throughout the peritoneum and even within distant organs such as the lung. The process is not neoplastic but the mechanism(s) by which endometrial tissue establishes itself in these extrauterine sites remains uncertain. Theories include:

• endometrial metaplasia

• retrograde flow through the fallopian tube at menstruation

• implantation after surgery

• bloodstream spread of viable endometrial fragments.

Box 28

Symptoms related to cyclical bleeding and subsequent inflammation:

• pain, often dyspareunia or dysmenorrhoea

• ovarian cysts (‘chocolate cysts’ containing altered blood)

• infertility (fallopian tube involvement)

• haematuria (bladder endometriosis)

• intestinal obstruction

• endometriotic nodules in abdominal surgical scars.

|

| Figure 57 |

Endometriotic foci may show proliferative and secretory activity in response to oestrogen and progesterone, in the same way as normal uterine endometrium. Endometriosis in the ovary is associated with clear cell adenocarcinoma (see below). The presence of endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium is called adenomyosis.

Polyps

Polyps are benign polypoid proliferations of glandular epithelium and stroma. They can arise in the endocervix and endometrium and may cause abnormal vaginal bleeding. Endometrial polyps occur most frequently after the menopause, and the incidence is increased in breast carcinoma patients receiving treatment with tamoxifen.

Ovarian cysts

Benign follicle (‘follicular’) and corpus luteum cysts are very common, but sometimes raise clinical suspicion of malignancy if seen on an ultrasound scan. Multiple bilateral follicular cysts, associated with ovarian enlargement, menstrual irregularities, hirsutism, obesity and infertility, are features of polycystic ovarian disease. The underlying cause seems to be abnormal release of pituitary hormones.

21.2. Dysplasia and neoplasia

You should:

• understand the principles and practice of the NHS Cervical Screening Programme

• have sufficient knowledge of neoplastic disease of the female genital tract to interpret histopathology reports of these tumours.

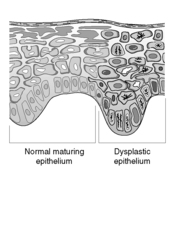

Dysplasia means abnormal growth. Dysplastic epithelium shows morphological changes of neoplastic cells but without evidence of invasion (Figure 58). Dysplastic changes include:

• increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio

• nuclear pleomorphism (variation in size and shape)

• nuclear hyperchromatism (increased intensity of staining)

• abnormal mitoses

• abnormal cellular crowding

• failure of epithelial maturation.

|

| Figure 58 |

Epithelial dysplasia occurs throughout the lower female genital tract:

• vulval intra-epithelial neoplasia (VIN)

• vaginal intra-epithelial neoplasia (VAIN)

• cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN)

• cervical glandular intra-epithelial neoplasia (CGIN)

• atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

The intra-epithelial neoplasia of squamous epithelium in the vulva, vagina and cervix (VIN, VAIN and CIN) is numerically graded from 1 to 3, according to the severity of dysplastic changes. Thus, CIN 1 is low-grade cervical dysplasia in which the cellular abnormalities are confined to the lower third of the squamous epithelium. In CIN 3 (high-grade dysplasia, also called carcinoma in situ), the entire thickness of the epithelium is abnormal, showing cytological features of malignant cells. However, there is no invasion of the atypical cells beyond the epithelial basement membrane and so there is no capacity for local spread or distant metastasis. CGIN describes dysplasia of endocervical glandular epithelium, and is classified as either low or high grade.

Only atypical hyperplasia is regarded as a high-risk premalignant change. Like other adaptive tissue changes, hyperplasia remains under the control of the eliciting stimulus. If the oestrogen excess is neutralised, for example by exogenous progesterone administration, the hyperplasia will regress. Even early stage endometrial carcinoma may be effectively treated in some cases with progestogens rather than surgery.

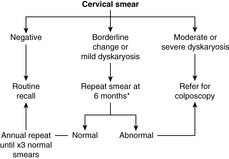

Cervical screening

The ability to recognise the abnormal cells from dysplastic cervical epithelium forms the basis of the NHS Cervical Screening Programme. All women between the ages of 25 and 65 are invited to have a cervical smear examination every 3–5years. A brush is used to gently remove cells from the surface of the cervix, ensuring that the cervical os is adequately visualised and the transformation zone is sampled. The cells are examined under the microscope for nuclear changes – enlargement, chromatin abnormalities and nuclear membrane irregularities – which might indicate a dysplastic or malignant lesion. The cytological changes are called dyskaryosis and graded as mild, moderate or severe. The screening programme was originally intended to identify dyskaryosis in the squamous epithelial cells, but it is possible to detect endocervical glandular abnormalities in some cases. Smears that show changes of HPV infection in the absence of dyskaryosis are still regarded as abnormal and warrant further follow-up, in view of the association between HPV and cervical neoplasia. Cytological abnormalities that do not amount to unequivocal dyskaryosis may be described as ‘borderline’, and again these changes require more regular follow-up smears to exclude significant disease.

The success of the programme depends on the detection and treatment of women with asymptomatic dysplastic lesions (CIN and CGIN) before they progress to invasive carcinoma. The degree of dyskaryosis in the cervical smear is an indication of the likely severity of dysplasia in the epithelium. High-grade smear abnormalities or persistent low-grade changes require colposcopic examination of the cervix by a gynaecologist, with tissue biopsy for histological confirmation of dysplasia (Figure 59). Treatment by laser, cold coagulation or tissue resection is followed up with regular smears, until it is safe for the patient to return to routine recall.

As with all screening programmes, there are advantages and disadvantages in participation, with both false-positive and false-negative results possible. False positives may be caused by:

• HPV infection without dysplasia

• cervical inflammation

• degenerate cellular changes that mimic dyskaryosis.

False negatives may result from:

• failure to sample the dysplastic focus within the smear

• small numbers of dyskaryotic cells being ‘missed’ by the cervical screener

• dyskaryotic cells being misinterpreted by the screener or cytopathologist.

Treatment of dysplastic lesions is not without significant adverse effects, as cervical stenosis secondary to tissue resection or ablation can cause infertility. Not all women with CIN, even of high grade, will definitely progress to invasive carcinoma if left untreated. However, the risk of a CIN lesion progressing to cancer cannot be predicted for individual women.

Neoplasia

Vulva

Cancer is relatively uncommon; the majority are squamous cell carcinomas (>90%) and usually occur in elderly women, but the incidence is increasing in younger women. Prognosis is closely related to spread, especially to inguinal and pelvic lymph nodes. Vulval malignant melanoma is rare, but has a poor prognosis. Extramammary Paget’s disease occurs in the vulva and anogenital region. This is an intra-epidermal proliferation of adenocarcinoma cells, which clinically manifests as a well-demarcated, crusted, red lesion. Unlike Paget’s disease of the nipple, underlying invasive malignancy is uncommon.

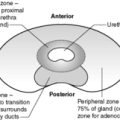

Cervix

Up to 90% of malignancies are squamous cell carcinomas (Table 38); the role of HPV in carcinogenesis, and the role of cervical screening in prevention of cervical cancer have already been discussed. Cervical cancers arise from the junctional region between squamous ectocervical epithelium and columnar endocervix, also known as the transformation zone. Adenocarcinoma accounts for approximately 10% of cervical malignancies, but is increasing in incidence.

| Incidence | Age >20, peak incidence around 40 |

| Risk factors | HPV infection with specific subtypes – multiple sexual partners, male partner with multiple previous partners, early age of first intercourse, smoking, HIV, herpes simplex type 2 |

| Protective factors | Celibacy, barrier contraception |

| Associated lesions | High grade CIN |

| Clinical presentation | Abnormal vaginal bleeding, pain/bleeding after sexual intercourse |

| Location | Initially arises in transformation zone |

| Macroscopic appearance | Exophytic, ulcerating or infiltrative mass |

| Histological features | Squamous cells +/− keratinisation |

| Pattern of spread | Local spread to uterine body, vagina, pelvic wall, bladder, ureters and rectum |

| Local and distant lymph nodes | |

| Distant metastases in liver and lung | |

| Prognosis (per cent 5-year survival) | Stage I 80–90% |

| Stage IV 10–15% | |

| Advanced tumours often cause death through renal tract obstruction |

Staging of cervical cancer

• Stage I – confined to cervix.

• Stage II – extends beyond cervix but does not involve pelvic wall or lower third of vagina.

• Stage III – involvement of pelvic wall or lower third of vagina.

• Stage IV – extension beyond pelvis or involvement of bladder or rectal mucosa.

Endometrium

Endometrial adenocarcinoma is the commonest invasive tumour of the female genital tract (Table 39).

| Incidence | Age >40, usually post-menopausal |

| Risk factors | Excessive oestrogen exposure – early menarche and late menopause, nulliparity, obesity (increased oestrogen production in peripheral fat), family history, diabetes, hypertension, oestrogen-producing tumours |

| Protective factors | Ovarian agenesis or removal |

| Associated lesions | Atypical endometrial hyperplasia |

| Clinical presentation | Abnormal vaginal bleeding (often post-menopausal) |

| Location | Anywhere in endometrium |

| Macroscopic appearance | Polypoid or diffuse growth pattern |

| Histological features | Mild, moderately or poorly differentiated according to the extent of glandular and solid growth pattern |

| Aggressive subtypes: clear cell carcinoma; serous papillary carcinoma | |

| Pattern of spread | Myometrium, cervix and pelvic organs Lymph nodes |

| Prognosis (per cent 5-year survival) | Most cases are Stage I (confined to uterus) and well or moderately differentiated, with 90% survival |

| Extrauterine spread, poor differentiation or aggressive histological subtypes have worse prognosis (20–50% survival) |

Myometrium

The commonest neoplasm arising in the female genital tract is the leiomyoma (benign smooth muscle tumour), also known as a ‘fibroid’. Growth of leiomyomas is stimulated by oestrogen, hence these are tumours of reproductive life that can grow rapidly in pregnancy but may atrophy after the menopause. Leiomyomas are often multiple and can reach many centimetres in diameter. They can cause pelvic pain, abnormal uterine bleeding, urinary symptoms and infertility or complications of pregnancy. Malignant smooth muscle tumours (leiomyosarcomas) are rare.

Ovary

The ovary can harbour a wide variety of benign and malignant neoplasms (Table 40), the more frequent examples are listed in Box 29. Most adult tumours arise from the surface epithelium of the ovary. In children germ cell tumours predominate. Most ovarian tumours (80%) are benign. However, ovarian malignancies cause more deaths than all other female genital-tract cancers combined. See Box 30 for clinical features.

| Incidence | Carcinoma >40years |

| Malignant germ cell tumours <30years | |

| Risk factors | Abnormal gonadal development |

| Nulliparity | |

| Family history | |

| BRCA1 gene | |

| Protective factors | Oral contraceptive use |

| Associated lesions | Breast cancer in BRCA1-related cases |

| Clinical presentation | Abdominal mass/pain, hormonal symptoms |

| Location | 20–65% of carcinomas are bilateral, germ cell malignancies usually unilateral |

| Macroscopic appearance | Partly cystic or solid masses, papillary areas, necrosis and haemorrhage |

| Histological features | Very variable, according to tumour type |

| Pattern of spread | Into peritoneal cavity – ascites |

| Contralateral ovary, omentum, local lymph nodes, lung, liver | |

| Prognosis | Carcinomas dependent on stage – spread beyond ovary usually means poor outcome |

| Some germ cell tumours respond well to chemoradiotherapy |

Box 29

Surface epithelial tumours (70%)

Benign:

• serous cystadenoma

• mucinous cystadenoma

• Brenner (transitional cell) tumour

Borderline (low malignant potential):

• serous borderline tumour

• mucinous borderline tumour

• serous cystadenocarcinoma

Malignant:

• serous adenocarcinoma

• mucinous adenocarcinoma

• endometrioid adenocarcinoma

• clear cell carcinoma

Germ cell tumours (20%)

Benign:

• cystic teratoma (‘dermoid cyst’)

Malignant:

• yolk sac tumour

• dysgerminoma

• choriocarcinoma (non-gestational)

Stromal tumours (10%): *

• fibroma, thecoma

• granulosa cell tumour

• Sertoli–Leydig cell tumours

Box 30

• Abdominal mass (tumour itself ± ascitic fluid)

• Pain/discomfort

• Symptoms related to hormone production (abnormal vaginal bleeding in oestrogen-producing tumours; masculinisation if excess androgens are produced)

• Raised serum CA125 or ovarian mass on pelvic ultrasound in women at risk of carcinoma (e.g. families with known BRCA1 gene)

Germ cell tumours

Germ cell tumours are a diverse group of lesions, the commonest of which is the benign dermoid cyst (mature cystic teratoma). The tumour consists of differentiated somatic tissues, and may include skin, with sebaceous glands and hair, teeth, fat, bone, cartilage, nervous tissue, respiratory epithelium and thyroid epithelium. Malignant germ cell tumours include yolk sac tumour, dysgerminoma (the female equivalent of seminoma) and choriocarcinoma (trophoblastic differentiation).

Stromal tumours

Stromal tumours are less common. Most are benign, but they may cause symptoms due to hormone production. Granulosa cell tumours, thecomas and fibromas can secrete oestrogens, and they may be associated with endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma. Some stromal tumours can produce androgens and clinically present with masculinisation. These include Sertoli–Leydig cell tumours and hilus cell tumours.

21.3. Pathology related to pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy

Extrauterine implantation of the fetus occurs in approximately 1 in 150 pregnancies. The fallopian tube is by far the commonest site; predisposing factors include pelvic inflammatory disease and previous tubal surgery. Tubal pregnancy frequently ruptures within the first trimester, with serious intraperitoneal haemorrhage. Ectopic pregnancy is also associated with a greater risk of hydatidiform mole (see below).

Spontaneous abortion

Early pregnancy loss (before the fetus is viable) can result from:

• chromosomal abnormalities

• congenital abnormalities

• uterine or placental malformations and abnormalities, including fibroids and cervical incompetence

• infections, including toxoplasmosis, listeriosis, mycoplasmosis and viral diseases.

Pre-eclampsia

Pre-eclampsia is the development of proteinuria, hypertension and oedema in late pregnancy. It is associated with young maternal age, twin pregnancy, diabetes, chronic hypertension and a history of pre-eclampsia in previous gestations. Central to the pathogenesis is defective uteroplacental blood circulation. This probably arises from failure of trophoblastic tissue to adequately invade the maternal spiral arterioles, resulting in placental ischaemia. Imbalance of arachidonic acid metabolites (prostacyclin and thromboxane) have also been identified and immune-related mechanisms may be important in some cases. Management includes monitoring, bed rest and antihypertensive medication. Delivery is curative, and may be expedited by caesarean section. Some cases may progress to eclampsia, a serious condition characterised by fits and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Gestational trophoblastic disease

Gestational trophoblastic disease is a group of conditions characterised by abnormal proliferation of trophoblastic tissue.

Hydatidiform mole

Hydatidiform mole is composed of abnormal chorionic villi, which are enlarged and oedematous with excess cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblast. There are partial and complete forms of mole. Both contain an abnormal karyotype. In complete mole, all of the genetic material is derived from paternal chromosomes (46 XX). Partial moles have triploidy with an extra set of paternal chromosomes (69 XXY). There is a marked geographical variation in incidence, with much higher rates in Asian than European or North American populations. Women over the age of 50 also have a greatly increased risk.

Molar pregnancy clinically presents in the mid-trimester of pregnancy with abnormal uterine bleeding, but earlier detection is possible with routine antenatal ultrasound. A fetus may be present in partial moles but not in complete moles. The uterus is often large for dates, and the swollen villi may be detected on scanning or on naked eye examination of aborted tissue passed vaginally. Serum levels of β-human chorionic gonadotrophin are markedly elevated. Serial measurement of this hormone is used in follow-up of treated patients to detect any recurrence or malignant transformation. Occasionally the molar tissue extends deeply into the myometrium and causes uterine rupture. Although hydatidiform mole is the commonest predisposing factor to gestational choriocarcinoma, progression to this neoplasm is rare (2%).

Gestational choriocarcinoma

Gestational choriocarcinoma is a malignant tumour of trophoblast, which develops following hydatidiform mole, abortion, normal pregnancy or ectopic gestation. The malignant trophoblast does not form chorionic villus structures. Gestational choriocarcinoma metastasises widely but is responsive to chemotherapy.

Placental site trophoblastic tumour

Placental site trophoblastic tumour is a rare neoplasm derived from intermediate trophoblast. No chorionic villi structures are formed.

Self-assessment: questions

True-false questions

1. The following statements are correct:

a. simple hyperplasia of the endometrium is usually a premalignant lesion

b. CIN inevitably progresses to invasive carcinoma if left untreated

c. the incidence of hydatidiform mole shows marked geographical variation

d. endometriosis frequently involves the ovaries

e. polypoid growths in the endometrium are always benign

2. HPV infection is associated with the following diseases:

a. squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva

b. adenocarcinoma of the cervix

c. serous cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary

d. condylomata lata

e. endometrial hyperplasia

3. Chronic endometritis:

a. is diagnosed histologically by the presence of lymphocytes in the endometrium

b. is associated with intrauterine contraceptive devices

c. can be part of pelvic inflammatory disease

d. can follow a normal pregnancy

e. is associated with endometrial carcinoma

4. The following primary malignant tumours commonly arise in the ovary:

a. cystic teratoma (‘dermoid cyst’)

b. Krukenberg’s tumour

c. leiomyoma

d. choriocarcinoma

e. embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma

5. Concerning pre-eclampsia:

a. symptoms begin in early pregnancy

b. it occurs most commonly in the first pregnancy

c. it is characterised by hypertension and haematuria

d. the fetus may be small for dates

e. the underlying pathology is defective uteroplacental circulation

6. The following are correctly paired:

a. intrauterine contraceptive devices – Actinomyces infection

b. toxic shock syndrome – Neisseria gonorrhoeae

c. infertility – endometriosis

d. nulliparity – ovarian carcinoma

e. smoking – squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix

Case history questions

Case history 1

A 68-year-old woman presents to her general practitioner with post-menopausal bleeding. She is mildly obese and diabetic. Her previous cervical smear tests have been normal. She was diagnosed with breast cancer 3years ago and has been taking tamoxifen.

1. What is the likely diagnosis?

2. What diagnostic procedure should be performed?

Case history 2

A 26-year-old woman attends the casualty department with acute abdominal pain. On questioning she describes her menstrual cycle as irregular. She has a previous history of pelvic inflammatory disease.

1. What differential diagnoses should you consider?

2. What immediate investigations are appropriate?

Viva questions

1. Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of a population-screening programme for cervical carcinoma.

2. How does pathological examination contribute to the management of patients with ovarian cancer?

Self-assessment: answers

True-false answers

1.

a. False. Simple hyperplasia without atypia is rarely associated with subsequent endometrial carcinoma. There is a much greater risk of atypical hyperplasia progressing to invasive malignancy.

b. False. The natural history of CIN is not fully known. Some, but not all, cases of high-grade CIN will progress to invasive carcinoma over a variable period of time. Lower-grade CIN may progress, remain stable, or regress. It is not possible to predict the risk of progression for an individual patient.

c. True.

d. True.

e. False. Most polyps in the endometrium are benign growths of endometrial glands and stroma. Submucosal leiomyomas (fibroids) can also project into the uterine cavity. However, endometrial carcinoma frequently has a partly exophytic polypoid growth pattern.

2.

a. True. HPV is associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva, vagina, cervix, anus and non-genital skin.

b. True. HPV DNA can be detected with similar high frequency in both squamous and glandular carcinomas of the cervix.

c. False.

d. False. Condylomata lata are genital lesions seen in secondary syphilis. Condylomata acuminata are HPV-related genital warts.

e. False.

3.

a. False. Lymphocytes can be seen in normal endometrium. Plasma cells are required for the diagnosis of chronic endometritis.

b. True.

c. True.

d. True. Retained placental material following normal vaginal delivery can become chronically inflamed.

e. False.

4.

a. False. Cystic teratomas do occur in the ovary, but these are benign germ cell neoplasms.

b. False. Krukenberg’s tumours are bilateral ovarian metastases, usually from gastric adenocarcinomas. The most common ovarian metastases, however, arise from primary malignancies elsewhere in the female genital tract or from the pelvic peritoneum.

c. False. Leiomyomas are benign smooth muscle neoplasms, which are very common in the myometrium.

d. True. Choriocarcinoma can arise as a non-gestational germ cell tumour in the ovary, or as a pregnancy-related uterine malignancy.

e. False. This rare malignant skeletal muscle tumour occurs in the vagina in young girls.

5.

a. False. Symptoms begin in the third trimester.

b. True.

c. False. Hypertension, proteinuria and oedema are characteristic.

d. True.

e. True.

6.

a. True.

b. False. The causative agent is Staphylococcus aureus.

c. True.

d. True.

e. True.

Case history answers

Case history 1

1. Abnormal vaginal bleeding may be:

• intermenstrual

• post-coital

• due to irregular menstrual cycles, often peri-menarchal and perimenopausal

• due to menorrhagia (heavy prolonged periods)

• post-menopausal.

There are many potential causes, including benign and malignant tumours and pregnancy-related bleeding. Abnormal bleeding during the reproductive years is most frequently related to altered oestrogen and progesterone balance (dysfunctional uterine bleeding), including anovulatory cycles and inadequate corpus luteum function. Post-coital bleeding is a classic symptom of cervical carcinoma, although benign causes are more commonly responsible. Post-menopausal bleeding – other than that related to hormone replacement therapy – suggests the presence of an endometrial polyp, endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial carcinoma.

2. The nature of any endometrial pathology must be established. Ultrasound scan may demonstrate increased endometrial thickness or a mass lesion. Histological sampling is necessary for definitive diagnosis. Suction biopsy may be performed by the general practitioner or in an out-patient clinic, but the tissue yield can be very low. More extensive material can be obtained by dilatation and curettage under general anaesthesia.

Case history 2

1. Potential serious causes of acute abdominal pain in a woman of this age include appendicitis, cholecystitis and ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Other possible gynaecological causes include endometriosis, an exacerbation of pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion and ‘mittelschmerz’ (cramping pain experienced in the middle of the menstrual cycle, due to ovulation).

2. It is vital to ascertain whether there is any chance of pregnancy and perform a pregnancy test. Ruptured tubal ectopic pregnancy occurs in the first trimester. It is a surgical emergency, and can cause shock with life-threatening intraperitoneal haemorrhage. The woman may be unaware of her pregnancy. Ultrasound scan helps confirm the diagnosis, as no gestational sac is identified within the uterus. The tubal abnormality might also be visualised. Often there is a little vaginal bleeding, which adds to the initial clinical suspicion of a ruptured ectopic gestation.

Viva answers

1. Comment: Be prepared to describe the pathological basis for cervical screening and to outline the management of a patient with an abnormal smear (Figure 59). You should know potential causes for false-positive and false-negative results and ways of minimising these – such as proper training of smear takers, cytoscreeners and pathologists, and regular audit.

2. Pathological examination is necessary for accurate initial diagnosis of ovarian carcinoma, either through ovarian histology or cytology of ascitic fluid. Histological examination of cancer resection specimens provides prognostic information, particularly related to tumour stage – spread to other organs and lymph nodes – and histological tumour type. Cytological examination of peritoneal washings obtained at operation forms part of the staging investigation. Serum tumour markers are specific proteins elaborated by the neoplasm, which can be helpful in initial diagnosis and during follow-up of treated patients to detect recurrent disease. Markers include CA125 in surface epithelial carcinomas, α-fetoprotein in yolk sac tumour and β-hCG in choriocarcinoma.