Eyes

HISTORY

HISTORY OF PRESENTING ILLNESS

What is the main or most serious complaint?

MEDICAL HISTORY

Systemic diseases that affect adherence to topical treatment: arthritis, dementia, tremor, stroke.

OCULAR EXAMINATION FOR GENERAL PRACTITIONERS

STRUCTURED EXAMINATION

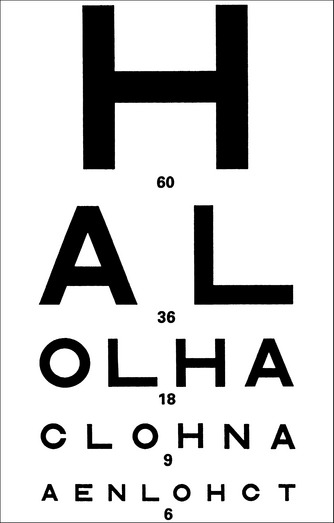

Visual acuity

Visual acuity near (NA)—ask the patient to read letters at 30 cm, with reading glasses if required.

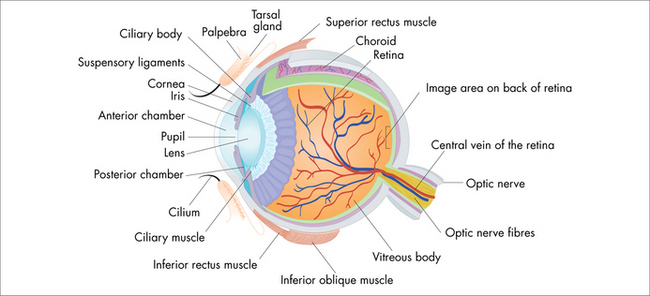

Pupil examination

Relative afferent defect (RAPD)—there is paradoxical initial pupil dilatation in the illuminated eye when the torch is swung across from the other eye. With the patient fixating steadily at an object across the room, shine the light steadily for a few seconds into one eye, then swing it across to the second eye, watching the movement of that (second) pupil. If the first movement is constriction, the pupil response is normal; if the first movement is dilatation (and then constriction), that demonstrates a defect. Such a defect means that there is a relative abnormality in that optic nerve (compared with its fellow). It suggests optic neuropathy, such as optic neuritis or glaucoma (early to moderate loss is usually asymmetric).

Ocular examination

Always compare one side with the other, and use adequate illumination and magnification.

OCULAR CONDITIONS

PREVENTION

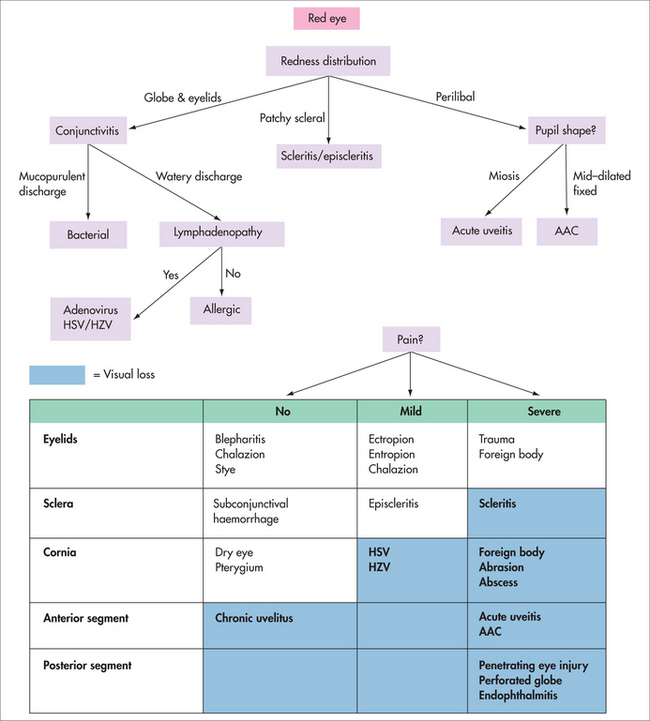

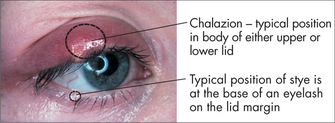

RED EYE

Red eye is very common and covers a broad spectrum of anterior segment diagnoses.

Conjunctivitis

Common

Bacterial conjunctivitis

(Staphylococcus epidermidis/aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae)

The conjunctiva appears ‘beefy red’ with yellow/green and mucopurulent discharge.

Uncommon

Episcleritis and scleritis

Episcleritis and scleritis are inflammatory conditions affecting the episclera and the sclera.

Episcleritis causes a tender red eye. The redness is over the bulbar sclera and maybe localised, sectoral or diffuse. There are no other ocular signs. It is rarely associated with an underlying systemic condition. Symptomatic treatment with lubricants and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drops leads to complete resolution.

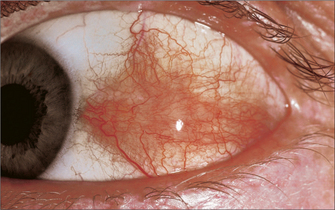

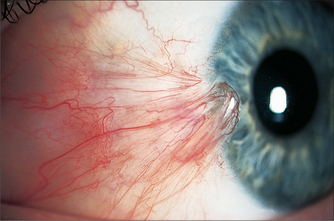

Pterygium and pinguecula

Damage occurs to the conjunctival basal cells as a result of sun exposure.

Occasionally, precancerous dysplasia and frank squamous cell carcinoma may mimic a pterygium.

Corneal disease

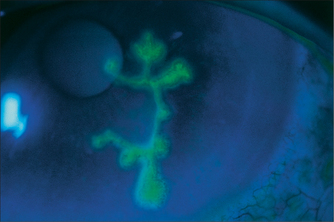

Abrasion, foreign body

A corneal abrasion, usually from trauma, is an epithelial defect that stains with fluorescein.

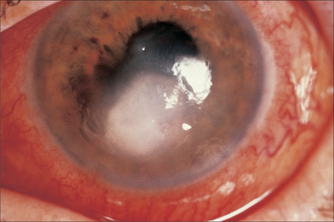

Keratitis (bacterial, viral)

A corneal abscess is seen as an area of white cell infiltrate, with an overlying epithelial defect and an inflammatory reaction in the anterior chamber (even to the extent of hypopyon). It is usually extremely painful and if not treated promptly may result in permanent visual loss, secondary to scarring, especially if central.

Uveitis

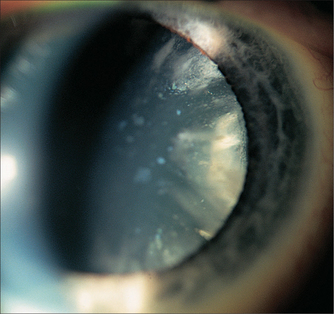

On examination there is decreased visual acuity, ciliary injection (perilimbal redness) and pupillary constriction (miosis). Slit lamp examination reveals anterior chamber cells and flare (white blood cells and protein).

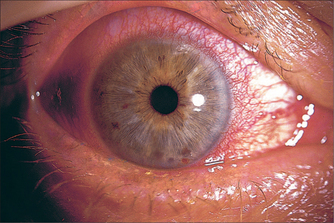

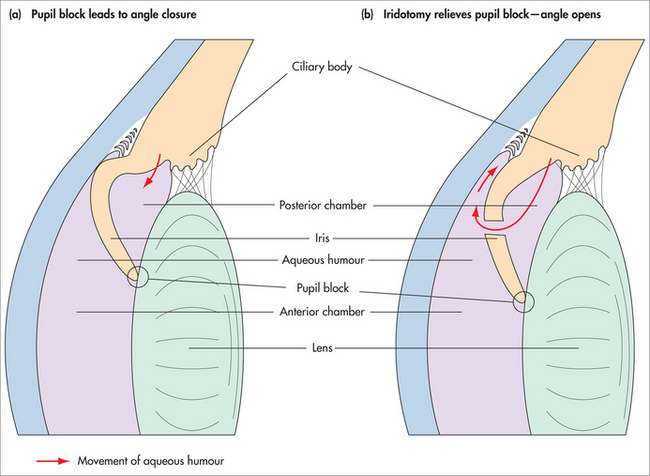

Acute angle closure

Warning signs may precede full closure: intermittent episodes of ocular pain and redness, with blurred vision and coloured rings around lights. In an acute angle closure crisis, pain is often severe and there may be nausea and even vomiting. Vision blurs as the cornea becomes cloudy, there is perilimbal injection, the pupil is mid-dilated and non-reactive to light, and digital eye pressure is extremely high.

LOSS OF VISION IN THE WHITE EYE

Cataract

Many causes for senile cataract have been investigated, without a single cause found. Sunlight exposure may contribute. Wearing sunglasses and a hat is a relatively simple protective measure. Diet has also been extensively studied, with varied results. In a recent paper, high dietary intake of lutein/zeaxanthin and vitamin E seem to be partly protective.3 Smoking is an independent risk factor.

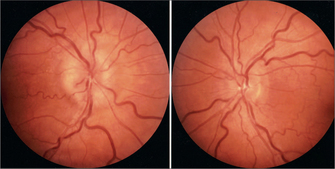

On examination there is decreased BCVA and opacity on red reflex in the visual axis.

Most patients will need to use antibiotic and steroid drops for around 1 month postoperatively, and attend follow-up with their ophthalmologist during this time. Even years later, opacification of the ‘bag’ (posterior capsule) in which the artificial lens sits may diminish vision. This is treated with a laser posterior capsulotomy.

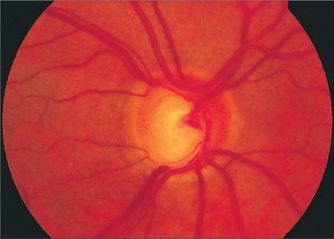

Glaucoma

Retinal and vitreous detachment

Symptoms associated with PVD usually settle spontaneously within months. However, the retina needs to be checked for tears and holes—these can be treated with laser. Retinal detachment often requires surgery.

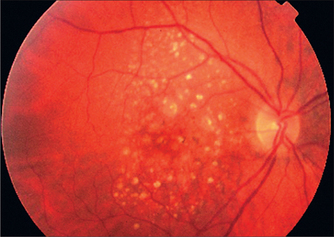

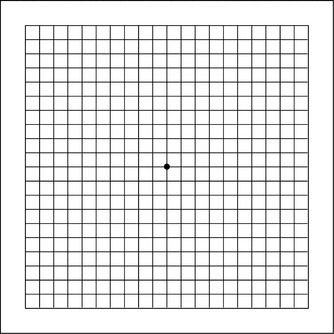

Age-related macular degeneration

There are no definitive dietary guidelines. A healthy diet low in animal fat and high in fish is recommended. A variety of vegetables of different colours, especially green leafy ones, may be beneficial.

The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS)4 found that a combination of antioxidant vitamins plus zinc helped slow the progression of intermediate macular degeneration to an advanced stage, which is when most vision loss occurs. The US National Eye Institute recommends that people with intermediate ARMD in one or both eyes or with advanced ARMD (wet or dry) in one eye but not the other take this formulation each day.5 However, this combination of nutrients did not help prevent ARMD, nor did it slow progression of the disease in those with early ARMD. The doses of nutrients are:

Retinal vascular disease

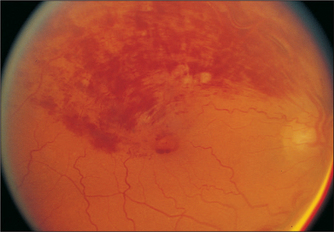

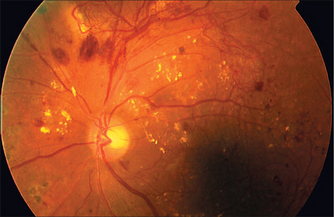

Diabetic retinopathy

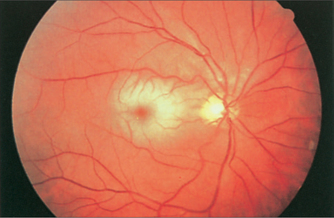

FIGURE 28.18 Proliferative diabetic retinopathy—superior neovascularisation, cotton wool spots, dot and blot haemorrhages

A dilated fundus examination needs to be performed by an ophthalmologist.

Vein occlusion

Vein occlusion occurs in patients with cardiovascular risk factors, and coagulative and autoimmune disorders. Central vein occlusion results in significant visual loss; branch occlusions may be asymptomatic.

The prognosis is best for small branch occlusions with good vision and no ischaemia.

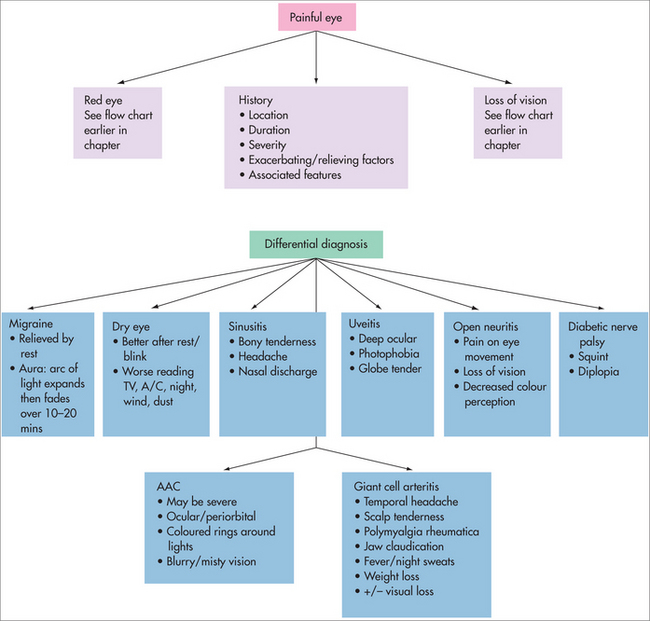

PAINFUL EYE

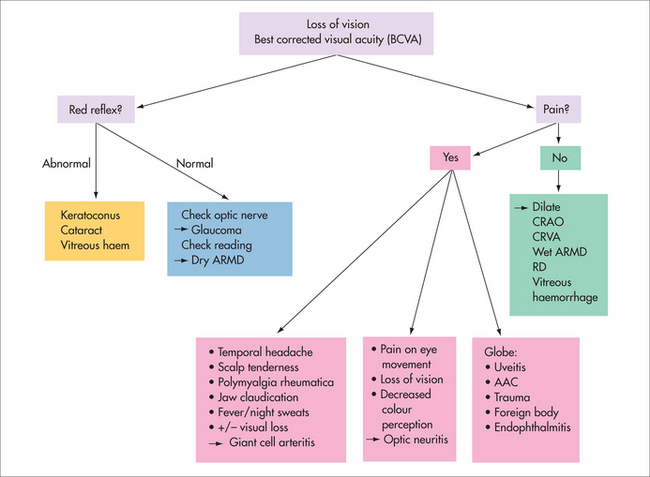

There is much overlap between red and painful eyes. Take a thorough pain history to elicit the differential diagnoses. The diagnoses may not be ocular (Fig 28.21).

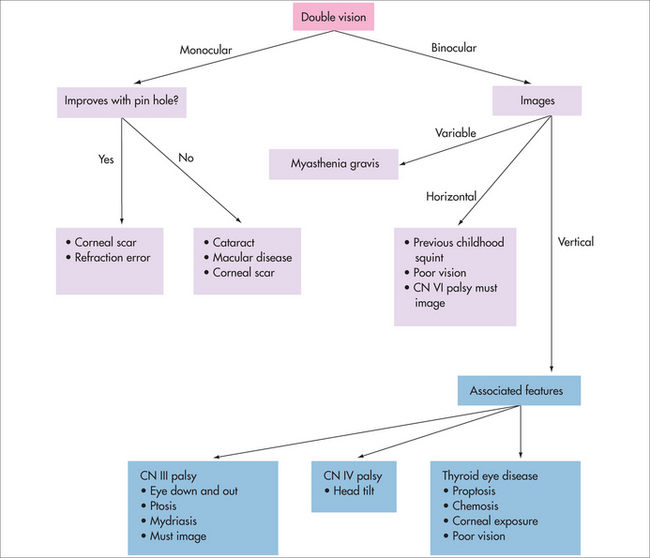

DOUBLE VISION

Is the diplopia (double vision) monocular (still seen with one eye closed) or binocular (only present with both eyes open)? (See Fig 28.22.) Monocular diplopia is usually caused by an anatomical change such as refractive error, cataract or retinal pathology in that eye. Binocular diplopia is discussed below.

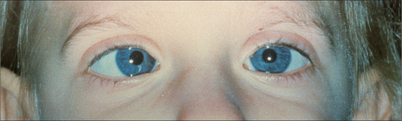

Neuro-ophthalmology and squint

A true squint is an ocular misalignment where the corneal light reflexes are asymmetrical (Fig 28.23).

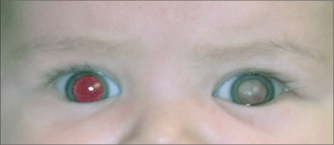

Squint in children is asymptomatic. Screening is necessary to avoid permanent visual loss from amblyopia (reduced BCVA despite normal visual pathways). In children, a white pupil reflex (leucocoria) is a very significant sign (Fig 28.24) and must be referred.

Important causes of leucocoria include retinoblastoma, cataract and high refractive error.

New-onset adult squint causes diplopia.

Glaucoma Australia. www.glaucoma.org.au.

Macular Degeneration Foundation. www.mdfoundation.com.au.

South East Asia Glaucoma Interest Group (SEAGIG). www.seagig.org.

American Academy of Ophthalmology Focal Points. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2000–2007.

Batterbury M, Bowling B. Ophthalmology: an illustrated colour text. 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2005.

Kanski J. Clinical ophthalmology, 5th edn. Edinburgh: Butterworth–Heinemann, 2003.

Kanski J. Clinical diagnosis in ophthalmology. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2006.

Rhee M, Pyfer M. The Wills eye manual. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

South East Asia Glaucoma Interest Group (SEAGIG). Asia Pacific Glaucoma Guidelines. Singapore: SEAGIG, 2004.

Webb LA. Manual of eye emergencies diagnosis and management. 2nd edn. Oxford: Butterworth–Heinemann, 2004.

1 Cho E, Hung S, Willet WC, et al. Prospective study of dietary fat and the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73(2):209-218.

2 Townend BS, Townend ME, Flood V, et al. Dietary macronutrient intake and five-year incident cataract: the blue mountains eye study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(6):932-939.

3 Moeller SM, Voland R, Tinker L, et al. Associations between age-related nuclear cataract and lutein and zeaxanthin in the diet and serum in the Carotenoids in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study, an Ancillary Study of the Women’s Health Initiative. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(3):354-364.

4 Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS Report No. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(10):1417-1436.

5 National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health. Age-related macular degeneration. Online. Available: http://www.nei.nih.gov/health/maculardegen/armd_facts.asp.