Chapter 13. Eyes

Rationale

Disorders of vision can interfere with a child’s ability to respond to stimuli, learn, and independently perform activities of daily living. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that assessment of the eye for children younger than 3 years include ocular history; vision, external eye, and ocular mobility assessments; and pupil and red reflex examinations. For children older than 3 years, the assessment also needs to include age-appropriate visual acuity measurement and ophthalmoscopy (if possible). Early detection and referral can minimize the effects of deficiencies in vision and prevent lifelong impairment. Vision disturbances can alert health practitioners to underlying congenital and acquired disorders.

Anatomy and Physiology

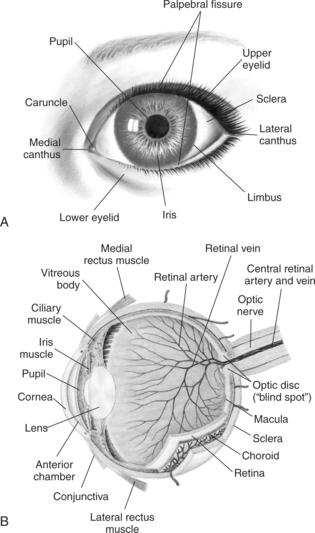

The eye is composed of three layers. The first, outermost layer consists of the sclera, or white of the eye, which is opaque, and the cornea, which is transparent (Figure 13-1). Underlying the cornea is the iris, which is colored and muscular. At its center is the pupil. The lens lies posterior to the pupil, which is suspended by ciliary muscles. A final layer, the retina, contains rods and cones, which receive visual stimuli and send them to the brain via the optic nerve. The fovea centralis, which appears as a small depression at the back of the retina, contains the most cones. The macula immediately surrounds the fovea centralis. The optic nerve enters the orb through the optic disk. Six muscles hold the eyes in position in their sockets. Coordinated movement of the muscles produces binocular vision. The eyelid, which protects the eye, is lined with the conjunctiva, which is vascular.

|

| Figure 13-1Normal structure of the eye. A, Anterior view. B, Cross-sectional view.(A from Hockenberry MJ et al: Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 7, St Louis, 2003, Mosby; B from Seidel HM et al: Mosby’s guide to physical examination, ed 5, St Louis, 2003, Mosby.)Elsevier Inc. |

At 22 days of gestation the eye appears, and by 8 weeks assumes its familiar form. Its structure and form continue to evolve until the child reaches school age. At birth, myelinization of the nerve fibers is complete and a pupillary response can be elicited. The newborn infant, however, has limited vision.

The neonate is able to identify the mother’s form and is aware of light and motion, as evidenced by the blink reflex. Searching nystagmus is common. The definitive ability to follow objects is not developed until about 4 weeks of life, when the infant is able to follow light and objects to midline. By 8 weeks the infant is able to follow light past midline, although strabismus might be evident.

Intermittent convergent strabismus is common until 6 months of age, then disappears. The muscles assume completely mature function by 1 year. The macula and fovea centralis are structurally differentiated by 4 months. Macular maturation is achieved by 6 years of age. Color discrimination is present between 3 and 5 months. The infant is normally farsighted at birth. Like small children, infants see well at close range. Visual acuity in infants ranges from 20/300 to 20/50 (Table 13-1). The iris usually assumes permanent color by 6 months, but in some children not until 1 year. Lacrimation is present by 6 to 12 weeks of age.

| Age | Visual Acuity |

|---|---|

| Birth | Infant fixates on objects 0.2 to 0.3 m (8 to 12 in) away (such as mother’s face) |

| 4 mo | 20/300 to 20/50 |

| 3 yr | ± 20/40 |

| 5 yr | 20/30 to 20/20 |

Equipment for Eye Assessment

▪ Penlight

▪ Nonstretchable measuring tape

▪ Tape

▪ Visual acuity chart or system (choice of chart or system based on age of child)

▪ Snellen Letter chart

▪ Blackbird Preschool Vision Screening System

▪ HOTV

▪ Allen cards

▪ Ishihara’s test (for color vision)

▪ Occluder

▪ Pirate eye patches

▪ Stereoscopic glasses

▪ Ophthalmoscope

Preparation

Ask the parent or child if the child seems to see well or if the child seems clumsy, holds books close to eyes, rubs eyes excessively, sits close to the television, has difficulty seeing the board (school-age child), or responds to approaching objects without blinking (infant). Ask if the parents think that the child’s eyes appear unusual or if they have noticed the child’s eyelids drooping or tending to close in an unusual way. Inquire about school performance; the presence of pain, headache, dizziness, or nausea while doing close work; discharge; excessive tearing; squinting; blurred or double vision; burning; itching; and light sensitivity. Alert the physician to any of these symptoms. Inquire about history of eye injuries. Inquire whether there is a family history of vision problems (use of glasses in parents or siblings, glaucoma, color blindness) and whether the child wears glasses, contact lenses, or a prosthesis.

Assessment of External Eye

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Position and Placement | |

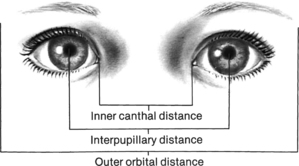

| Note whether the eyes are wide set (hypertelorism) or close set (hypotelorism). Measure the distance between the inner canthi, if in doubt (Figure 13-2). | Inner canthal distance averages 2.5 cm (1 in). |

| Wide spaced eyes can be a normal variant in some children. | |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Hypertelorism is present in Down syndrome. | |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Observe for vertical folds that partially or completely cover the inner canthi. | Epicanthal folds are normally seen in Asian children and in some non-Asian children. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Epicanthal folds can indicate | |

| Down syndrome, renal agenesis, glycogen storage disease, or fetal alcohol syndrome. | |

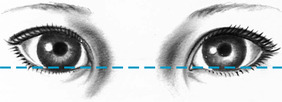

| Observe the slant of the eyes by drawing an imaginary line across the inner canthi (Figure 13-3). | The palpebral fissures lie horizontally along the imaginary line. |

| Asian children normally have an upward slant to their eyes. | |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Upward slant of the eyes is present in Down syndrome and can be associated with infants exposed to AIDS/HIV. | |

| Short palpebral fissures can indicate fetal alcohol syndrome. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Observe the eyelids for proper placement. | The eyelid falls between the upper border of the iris and the upper border of the pupil. |

| Entropion, or turning-in of the eyelid, is a normal variant in Asian children. | |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Appearance of sclera between the upper lid and iris (sunset sign) is present in hydrocephalus, although it can be a normal variant. | |

| Drooping of the eyelid over the pupil (ptosis) can be a normal variant or can signal a variety of disorders, such as paralysis of the oculomotor cranial nerve or myasthenia. | |

| If the eyelids turn inward (entropion), the corners can become irritated by the eyelashes. | |

| If the eyelids turn outward (ectropion), the conjunctiva is exposed. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Lid lag and incomplete closure of the eyelid can indicate hyperthyroidism. | |

| Eyebrows | |

| Inspect the eyebrows for symmetry and hair growth. | Eyebrows normally are shaped and move symmetrically. |

| They do not meet in midline. | |

| Eyelids | |

| Observe distribution and condition of eyelashes. | Eyelashes curl outward. |

| Inspect eyelids for color, swelling, discharge (amount, type), and lesions. | Eyelids normally are the same color as the surrounding skin. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Flat, pink areas on eyelids can be telangiectatic nevi or “stork bite marks,” which disappear by 1 year of age. | |

| A painful, red, swollen eyelid can indicate a stye. | |

| A nodular nontender area can be a chalazion (cyst). | |

| Puffiness can be related to thyroid or renal disorders. | |

| Swelling, redness, and purulent discharge can be related to inflammation of the lacrimal sac (dacryocystitis), often the result of a blocked tear duct, which can disappear as an infant reaches 6 months of age. | |

| If the area around the eyelids appears sunken, the child might be dehydrated. | |

| Shadow under the eyes can indicate fatigue or allergy. | |

| Persistent tearing or discharge can indicate infection, allergy, lacrimal duct obstruction, or glaucoma. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Conjunctivae | |

| Inspect the lower lid by pulling down as the child looks up. Inspect the upper lid by holding the upper lashes and pulling down and forward gently as the child looks up. | The conjunctivae should be pink and glossy. Yellow striations along the edge are sebaceous glands near the hair follicle. The lacrimal punctum appears as a tiny opening in the medial canthus. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Redness of the conjunctivae can be related to bacterial or viral infection (including gonorrhea and chlamydia), allergy, or irritation. | |

| Redness and discharge can be indicative of avian flu, if there is also fever, cough, sore throat, myalgia, respiratory distress, and history of direct or indirect contact with chickens or pigs. | |

| A cobblestone appearance of the conjunctivae can accompany severe allergy. | |

| Excessive pallor of the conjunctivae can accompany anemia. | |

| Inspect the bulbar conjunctivae for color. | The bulbar conjunctivae should be clear and transparent, allowing the white of the sclerae to be clearly visible. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Redness can indicate fatigue, eyestrain, irritation, or bleeding disorders. | |

| Overgrowth of conjunctival tissue (pterygium) can cover the cornea. | |

| Inspect the sclerae for color. | The sclerae should be white and clear. Tiny black marks in dark-skinned children are normal. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Clinical Alert | |

| Yellow appearance can indicate jaundice. | |

| Bluish discoloration can indicate osteogenesis imperfecta, glaucoma, later stages of increased bilirubin, or prenatal exposure to AIDS/HIV. | |

| Pupils and Irises | |

| Inspect the irises for color, shape, and inflammation. | Irises of different colors can be normal. |

| Irises should be round and clear. | |

| The cornea covering the iris and pupil should be clear. | |

| Clinical Alert | |

| A notch at the outer edge of the iris (coloboma) can indicate a visual field defect and should be reported. | |

| White or light speckling of the iris (Brushfield’s spots) can indicate Down syndrome. | |

| Absence of color and a pinkish glow can indicate albinism. | |

| Dome-shaped, clear to yellow or brown elevations (Lisch nodules) on the iris develop near the onset of puberty in children with neurofibromatosis. | |

| Inspect the pupils for size, equality, and response to light. Observe and record the pupil size in normal room light. | Pupils are normally round and equal in size, although inequality is not uncommon and can be nonpathologic if other findings are normal. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Darken the room and observe the response of each pupil when light is directly shone into it (direct light reflex) and quickly removed. | Pupils should respond briskly to light. In the consensual reaction the pupil should constrict when light is shone in the contralateral eye. |

| Assess the response of the pupils to light as the light is moved toward the face (accommodation). | |

| In infants younger than 5 months, pupil inequality is common but should be considered significant if it persists and is accompanied by other central nervous system findings. | |

| Assess the consensual light reflex by placing your nondominant hand down the midline of the eye and observing what happens when light is shone into the opposite eye. In infants younger than 5 months, check pupillary reaction by covering each eye with a hand and then uncovering the eye. | |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Constriction of the pupils (miosis) can occur with iritis and with morphine administration. | |

| Dilation of pupils (mydriasis) can be related to emotional factors, acute glaucoma, some drugs, trauma, circulatory arrest, and anesthesia. | |

| Pupils that are equal, round, and react to light and accommodation are recorded as PERRLA. | |

| Fixed unilateral dilation of a pupil can indicate local eye trauma or head injury. | |

| White or grayish spots in the pupils can indicate cataracts. |

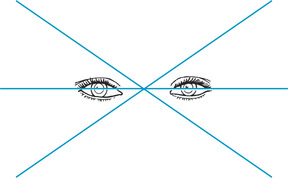

Assessment of Extraocular Movement

Two tests are commonly used to test binocular vision: the corneal light reflex test and the cover test. The random-dot-E stereoscopic test can be used to test depth perception in older children, which can indicate lesser degrees of imbalance in the eye muscles. The eyes are also assessed for nystagmus (rapid, jerky movements of the eye) through field-of-vision testing.

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Corneal Light Reflex Test (Red reflex gemini or Hirschberg test) | |

| Assess for strabismus by shining a light directly into the eyes from a distance of about 40 cm (16 in). Observe the site of the reflection in each pupil. | Normally the light falls symmetrically on each pupil. Epicanthal folds, often found in Asian children, can give an impression of malalignment. |

| Intermittent alternating convergent strabismus is normal during the first 6 months of life. | |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Report any malalignment. If malalignment is present, the light falls off center in one eye and neither eye deviates. | |

| Infants with a birth weight of less than 1500 gm (3.3 lb) are more prone to muscle imbalance and warrant early, periodic screening. | |

| Cover Test | |

| Ask the child to look at your nose; then cover one of the child’s eyes. Observe whether the uncovered eye moves. Uncover the occluded eye and inspect for movement. | Clinical Alert |

| Movement can indicate strabismus. Record the direction of any eye movement. Refer for further testing. | |

| Random-dot-E Stereoscopic Test | |

| Test cards are held 40 cm (16 in) from the child’s eyes. | Clinical Alert |

| Failure to identify the E card correctly may indicate lesser degrees of muscle imbalance. | |

| The child wears stereoscopic glasses while looking directly at cards that are presented randomly and from different angles. The cards consist of a blank card, a card with a raised E, and one with a recessed E. The child must correctly identify the E card on four out of six attempts. | |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Field of Vision | |

| Ask the child to follow a finger or shiny object through the six cardinal fields of gaze (Figure 13-4). Children younger than 2 or 3 years of age might not be able to cooperate with this test. Observe the eye movements of the younger child as the examination progresses. | A few beats of nystagmus in the far lateral gaze are normal. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Report easily elicited nystagmus. | |

Assessment of Color Vision

Color vision can be assessed by using Ishihara’s test, which is composed of a set of cards with a series of round dots in the shape of a figure or number. The figures or numbers are not discernible by persons with impaired color vision. Color vision deficits and blindness can be indicated in younger children who have difficulty coordinating clothes colors or who have difficulty discerning their colors in school activities.

|

| Figure 13-2Anatomic landmarks of the eye.(From Hockenberry MJ et al: Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 7, St Louis, 2003, Mosby.)Elsevier Inc. |

|

| Figure 13-3Upward palpebral slant.(From Hockenberry MJ et al: Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 7, St Louis, 2003, Mosby.)Elsevier Inc. |

|

| Figure 13-4Six cardinal fields of gaze. |

Assessment of Visual Acuity

Testing of visual acuity in children is not simple and can be directly affected by the child, nurse, and environment. There is no simple method to accurately test visual acuity in children younger than 3 years.

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Observe whether the infant blinks and exhibits dorsiflexion in response to light. | Clinical Alert |

| Report absence of blink reflex. | |

| Observe whether the infant of 4 weeks or older is able to fixate on a brightly colored object, maintain fixation, and follow the object through various gaze positions. | Drowsiness can interfere with the infant’s interest in the object and ability to cooperate. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Report inability to follow an object, and reassess when older. | |

| Snellen Letter Chart | |

| Hang the Snellen chart so that it lies smoothly and firmly on a light-colored wall and so that there is no glare on the chart. | Clinical Alert |

| Refer children with a two-line difference between eyes, even within pass range. | |

| The chart should be placed so that the 20 to 30 foot lines are at the eye level of 6 to 12 year old children who are seated. Mark the correct distance from the chart with tape or with footprints. Have the child stand so that heels are touching the distance line or seated so that the back of the chair is on the line. Although most charts are designed to test from a distance of 6.2 m (20 ft.), a distance of 3.1m (10 ft.) is recommended for children as this distance enhances focus and cooperation. | |

| Refer children, three years of age who have vision in either eye of 20/50 or less. | |

| Refer children of all other ages who have vision in either eye of 20/40 or less. Refer all children who show signs of possible visual disturbances (for example, squinting, excessive tearing, or excessive blinking). | |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Test both eyes first, then the right eye, then the left eye by having the child cover each eye with an occluder, or with young children, a pirate patch. Unless the child has very poor vision, begin with the line on the chart that corresponds to a distance of 12.2 m (40 ft). If the child is unable to read this line, move up the chart until a line is found that the child can read and then begin to move down the chart again, until the child is unable to read the line. The child must be able to see four of six symbols or three out of four symbols on a line to correctly visualize the line. | |

| Record the results as a fraction, with the numerator representing the distance from the chart and the denominator the last line read correctly (hence 20/20 means that the child read the 20-foot line correctly from a distance of 20 feet or 6.2 m.) | |

| If testing from a distance of 3.1 m (10 ft), convert fractions to the standard 20-foot scale by multiplying the numerator by 2. Test with glasses or contact lenses if the child wears them. (A Snellen number chart is available for children who know their numbers.) |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| If using the Snellen E or tumbling E chart, have the child indicate the direction of the E’s “legs” with his or her fingers or with a cardboard E. Use the 20/100 E to determine whether the child understands what to do. Proceed as for regular Snellen testing. | |

| The tumbling E is useful for children 4 years and older who are unable to read numbers and letters. | |

| HOTV Test | |

| The HOTV test involves a wall chart composed of Hs, Os, Ts, and Vs. The child is asked to match the symbol to which the examiner is pointing on the chart with the correct letter on a board that the child holds. | |

| Blackbird Preschool Vision Screening System | |

| Using either the wall-mounted chart or flashcards, ask the child to indicate direction of the bird’s flight. This system is useful for nonreaders and children whose first language is not English. | |

| Allen Cards | |

| Show the child the cards at close range and have the child name the pictures from a distance of 4.6 m (15 ft). Test each eye, if possible. The Allen cards are useful for young children (2 to 4 years) who are unable to perform the HOTV or tumbling E tests. | The child should be able to name three of seven cards in a maximum of five tries. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Visual Acuity in Young Infants | |

| Assess for visual acuity in young infants by shining a light into the eyes and noting blinking, pupil constriction, and following of light to midline. | Clinical Alert |

| Fixed pupils, constant nystagmus, and slow lateral movements can indicate visual loss in young infants. | |

Ophthalmoscopic Examination

Ophthalmoscopic examination requires practice and patience, as well as a cooperative child. In young infants and children it might be possible to elicit only the red reflex. The retina, choroid, optic nerve disk, macula, fovea centralis, and retinal vessels are visualized with the ophthalmoscope.

Darken the room. Sit the child on the parent’s lap or examination table or lay the child on the table. Have the child remove glasses unless glasses are worn to correct astigmatism, which can distort images. Use your right hand and eye to examine the child’s right eye and your left hand and eye for the left eye. Ask the child to gaze straight ahead, or use your nondominant hand to attract the child’s gaze away from the light source of the ophthalmoscope.

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Perform the examination in a dimly lit room and have the child remove glasses, unless glasses are worn to correct astigmatism, which can cause distortion of images. Set the dial of the ophthalmoscope at +8 to +2. Approach from a distance of 30.5 cm (12 in), centering the light in the eye. The pupil glows red (red reflex). Gradually move closer and change the dial of the ophthalmoscope to plus or minus diopters to focus. Move the ophthalmoscope up and down and from side to side to visualize eye structures. | In infants the optic disk is pale and the peripheral vessels are not well developed. The red reflex appears lighter in infants. |

| In children the red reflex appears as a brilliant, reddish-yellow (or light gray in dark-skinned, brown-eyed children) uniform glow. The optic disk is creamy white to pinkish, with clear margins. At the center of the optic disk is a small depression (the physiologic cup). Arteries are smaller and brighter than veins. The macula is the same size as the optic disk and located to the right of the disk. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| The fovea is a glistening spot in the center of the macula. | |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Report a partial or white reflex, dark spots in the red reflex, blurring of the disk margins, bulging of the disk, and hemorrhage. | |

| Blockage of the red reflex can indicate cataract. | |

| Papilledema in an older child can indicate acute head injury. Retinal hemorrhage is also associated with acute head injury and Shaken Baby syndrome. |

Related Nursing Diagnoses

Risk for injury: related to sensory dysfunction.

Risk for trauma: related to reduced eye-hand coordination, poor vision.

Altered health maintenance: related to significant alteration or lack of communication skills.

Social isolation: related to factors contributing to the absence of satisfying personal relationships.

Impaired social interactions: related to communication barriers.

Altered parenting: related to lack of knowledge about child health maintenance, illness.

Altered family processes: related to shift in health status of a member, situation transition.

Sensory/perceptual alterations (visual): related to altered sensory perception.

Disorganized infant behavior: related to sensory deprivation.

Risk for altered development: related to vision impairment.

Impaired tissue integrity: related to irritants, mechanical factors, chemical factors, lack of knowledge.

Impaired comfort: related to infection, irritation, trauma, strain.