Eye and dental complications

Eye injury

Postoperative visual loss

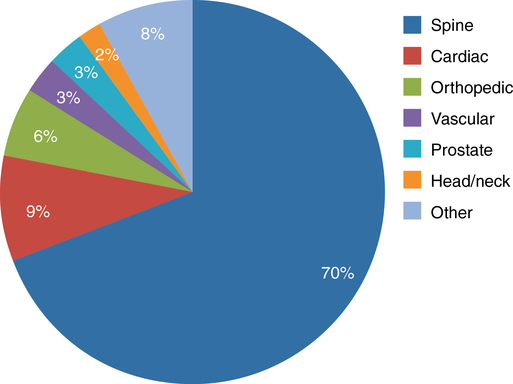

Postoperative visual loss (POVL) is a rare but devastating complication seen most commonly following spine, cardiac, and head and neck surgical procedures (Figure 242-1). During the 1990s, the incidence of POVL seemed to be increasing, so in 1999 the ASA Committee on Professional Liability established the ASA POVL Registry to tabulate data on POVL following nonocular operations. Seven years later, a review of the registry identified 93 cases of POVL associated with spine operations; most were caused by ischemic optic neuropathy (ION)—either anterior or posterior—and not by compression of the globe. Only 10 of the patients had a central retinal artery occlusion, whereas the remainder had ION. Patients with ION, as compared with those without ION, were relatively healthy, were more likely to have an associated blood loss of 1000 mL or greater, or were more likely to have had an anesthetic duration of 6 h or longer; such conditions were found in 96% of the patients.

Dental injury

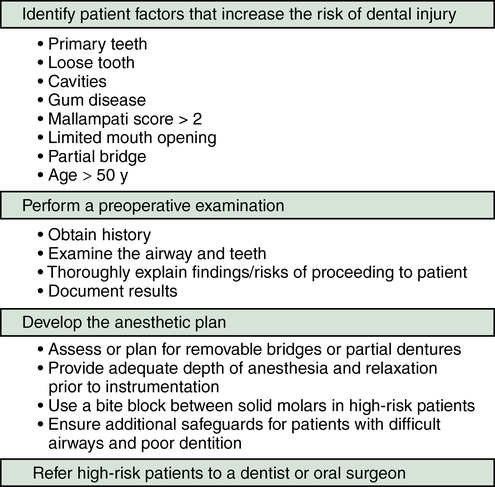

Prevention

A thorough preoperative evaluation and examination of the oropharynx should be performed, not only to document whether the patient has a difficult airway, but also to identify those patients with loose or carious teeth. In patients with poor dentition, consideration should be given to postponing the procedure if time permits to allow patients to see their dentists prior to the planned surgical procedure to attend to the dental problem (Figure 242-2). Because two thirds of injuries in one review were due to preexisting conditions (e.g., caries, prostheses, loose or damaged teeth, a single isolated tooth, or functional limitations), the anesthesia provider should document these in the medical record. If the patient requests to proceed after the risks of dental injury have been explained, documentation of the examination and of the counseling should be included in the consent form that the patient signs. Relying on a preprinted standardized “Consent for Anesthesia” that includes “dental injury” as one of the complications of anesthesia provides little protection from a medicolegal perspective.

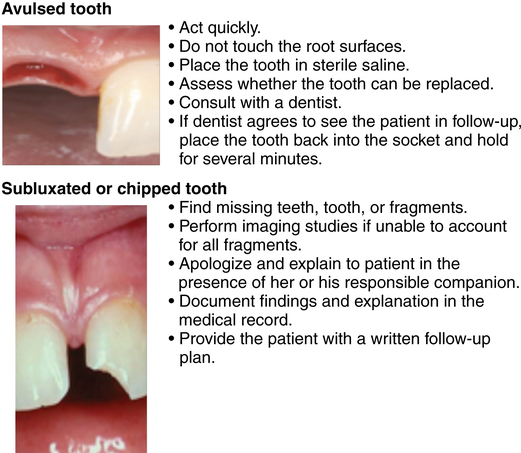

Treatment and management of dental injury

Despite our best efforts, injury to teeth can and will occur. Anesthesia departments should have a protocol in place to guide the management and care of dental injuries (Figure 242-3). This protocol should include, at a minimum, the following items:

• Any missing teeth or fragments must be found. If the teeth or fragments are not identified, the patient should have a chest radiograph and an abdominal radiograph, if necessary, to identify fragments that may have been aspirated or swallowed.

• In children, the loss of a primary tooth does not require treatment. However, if a permanent tooth is avulsed, it should be stored in cool sterile saline until placed back in the socket from which it came.

• Once the patient has recovered from anesthesia, she or he should be offered an explanation and an apology. A plan for postoperative care should be documented in the patient’s medical record. If indicated, an oral surgical consultation should be obtained while the patient is still in the postanesthesia care unit, or, if treatment is not urgent, arrangements should be made, with a written plan given to the patient, for the patient to see his or her personal dentist.