CHAPTER 32 Extrinsic Contracture: Lateral and Medial Column Procedures

INTRODUCTION

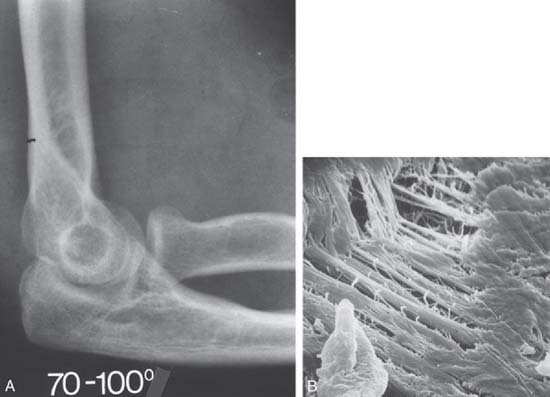

Of the numerous potential causes for elbow stiffness, the causes and pathophysiologic mechanisms dictate treatment and affect prognosis. Extrinsic contracture typically involves only the soft tissues around the elbow, sparing the joint space (Fig. 32-1).45 Post-traumatic stiffness is one of the most frequent causes of this kind of contracture47; however, it can also occur in association with other causes, such as congenital or developmental disease, osteoarthritis or inflammatory arthritis, burns, and head injury. Intrinsic contracture is associated with joint articular involvement and is not discussed here (see Chapters 33 and 69).

Several options have been proposed for treatment of elbow contracture. Conservative treatment sometimes gives good results if the contracture is of short duration4,6,13,15,16,21,23,38,46; however, its efficacy is unpredictable. With failure of nonoperative treatment, surgical release may be indicated. Most employ an open procedure, and several have been described.1,3,7,9–12,17,19,22,26,27,31–34,39,43,51,53,55,56,58–64 There is, however, an increasing interest in using an arthroscopic procedure.5,29,35,49,52,54,57

ETIOLOGY AND INCIDENCE

An extrinsic contracture usually involves the periarticular soft tissue without involving the articulating surface. Contracture may involve the capsuloligamentous structures or muscle tissue. Ectopic ossification is also considered an extrinsic condition. Bone may form a bridge across the joint or form in the capsule or in the muscle crossing the joint. Trauma is the major cause of extrinsic stiffness, especially elbow dislocation, with or without fracture.30,41 The brachialis muscle that crosses the anterior capsule36 tears with dislocation, developing scar tissue or ectopic bone when healing,49 often associated with contracture of the capsule.25,47,65 Pain, swelling, limited motion, and contracture after this type of elbow trauma then leads to the irreversible changes that constitute extra-articular ankylosis. Collateral injuries can contribute to elbow ankylosis from permanent contracture.8,24,28 In trauma, length of immobilization has also been recognized as a major contributor to postinjury contracture. The precise incidence of elbow stiffness after trauma is difficult to identify and is as much a function of the severity of injury as of the initial treatment. In adults, nontraumatic elbow contractures are usually caused by a primary inflammatory process. With osteoarthritis, a mild inflammatory synovitis occurs with periarticular fibrosis and osteophytic new bone formation.50 The articular surface of the joint is intact, but osteophytes are present at the tip of the olecranon and at the tip of the coronoid process.3 Hemophilia,14 juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, acute or chronic septic arthritis, and periarticular new bone formation after head injury18,37,42 can produce ankylosis of the elbow but often involve the joint space. Congenital stiffness is rare and is often associated with bone malformation or soft tissue dysplasia.2

PRESENTATION AND CLASSIFICATION

Generally, the patient initially notices loss of full extension but no limitation of activity. The first complaint is pain in terminal extension. Concurrent with this is the recognition that midarc motion typically is not painful, a finding that confirms the extrinsic character of the stiffness. Occasionally, full flexion also produces pain. Flexion contracture develops progressively.

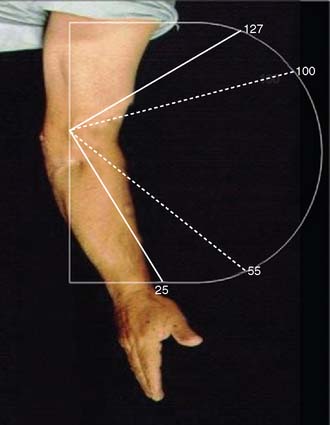

In addition to classifying elbow contracture according to extrinsic and intrinsic lesions, age of the patient, severity of the stiffness, and distribution of the contracture are also important for evaluating what might be expected from the surgery. Thus, the stiffness may be graded as very severe, severe, moderate, or minimal, depending on data on the amount of residual arc of flexion.1,17,48 The stiffness is considered very severe when the total arc is 30 degrees or less, severe when it is between 31 and 61 degrees, moderate between 61 and 90 degrees, and minimal when it is greater than 90 degrees. Based on the functional arc of motion described by Morrey and colleagues,48 the distribution of the contracture referable to the 30- to 130-degree arc is also considered.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Limited involvement and limited soft tissue contracture argue against these procedures. An inadequate period of an appropriate splint program is also a contraindication. Intrinsic lesions are not absolute contraindications, but a lower level of improvement has to be expected in these cases.39

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

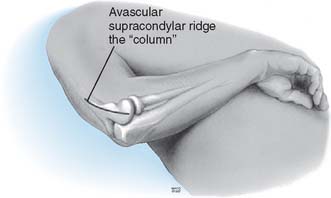

Before surgery, the decision must be made to approach the capsule from the lateral or medial aspect. If the ulnar nerve is to be addressed or there is extensive medial or coronoid arthrosis, the medial approach is of value. If the radiohumeral joint is involved or if a simple release is all that is required, the lateral “column” procedure is carried out (Fig. 32-2).

TECHNIQUE: COLUMN PROCEDURE

DISADVANTAGES

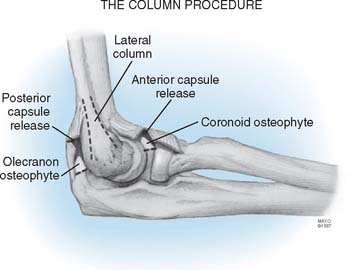

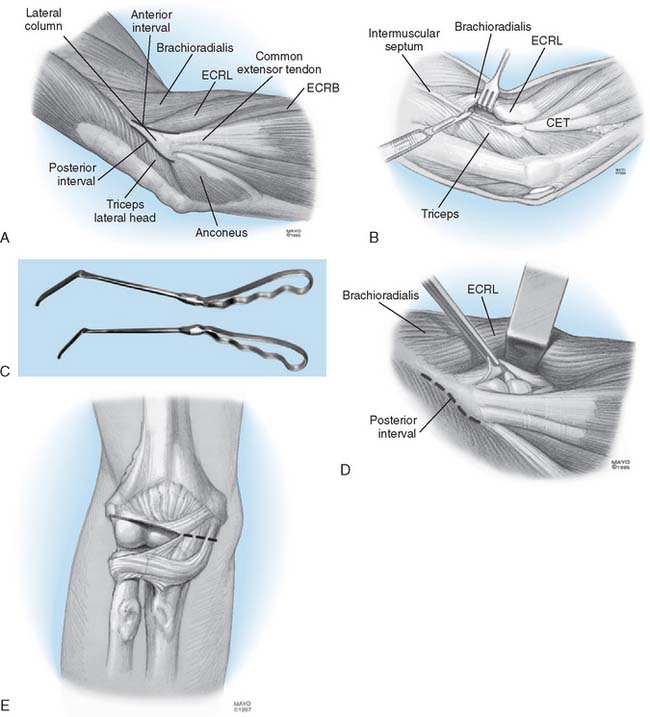

The column procedure consists of open arthrolysis of the elbow through a limited lateral approach, with the aim of releasing the anterior capsule safely but also of releasing the triceps attachment and posterior capsule, if necessary. The exposure employs a limited skin incision of only about 6 cm, but this is sufficient to remove coronoid or olecranon osteophytes (Fig. 32-3).

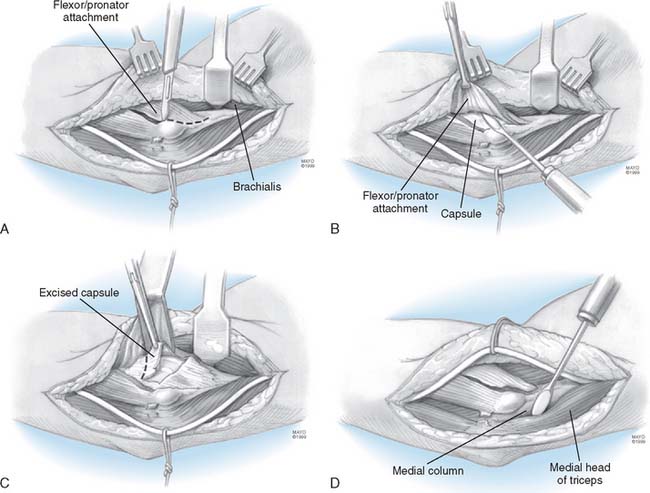

To release the anterior capsule with minimal disruption of normal tissue, the origin of the distal fibers of the brachioradialis and the extensor carpi radialis longus are identified (Fig. 32-4A). Release of the fleshy origin of the extensor carpi radialis longus and the distal fibers of the brachioradialis from the humerus provides direct access to the superior aspect lateral of the capsule (see Fig. 32-4B). The capsule is entered anteriorly at the radiohumeral joint, an approach that allows identification of the thickness and orientation of the capsule. The brachialis muscle is swept from the anterior capsule with a periosteal elevator. A specially designed retractor protects the brachialis muscle, the median nerve, and the brachial artery (see Fig. 32-4C). The anterior capsule is grasped and excised, at least to the level of the coronoid. The medial most aspect of the capsule is often difficult to visualize clearly but can be palpated. It is incised to complete the release (Fig. 32-4D). At this juncture, if extension is full or within 10 degrees of normal and the radiographs reveal no olecranon spur, no additional release is needed and the wound is closed. If scarring is extensive and adhesions involve the posterior capsule, the triceps is elevated from the posterior aspect of the humerus. The posterior capsule is released, and the olecranon fossa is cleaned of soft tissue (see Fig. 32-4E). The tip of the olecranon is excised when osteophytes are present. The range of flexion and extension at the elbow is assessed. If flexion is essentially normal, nothing more need be done posteriorly.

FIGURE 32-4 A limited Kocher skin incision measuring 6 cm is made over the lateral epicondyle. A, The anterior and posterior aspects of the lateral column are identified. B, The extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) and distal fibers of the brachioradialis are elevated. C, A special retractor facilitates exposure and protection of the anterior structures. D, The anterior capsule is isolated from the brachialis and identified by arthrotomy at the anterior radiohumeral joint. E, The lateral capsule is excised as widely as possible, and the remaining medial capsule is incised. The posterior capsule is identified (D) and excised as necessary by elevating the triceps from the lateral osseous column. The posterior aspect of the ulnohumeral joint is exposed and the capsule incised (see Fig. 32-3). ECRB, extensor carpi radialis brevis.

DESCRIPTION OF EXPOSURE

EXPOSING THE ANTERIOR CAPSULE FOR EXCISION AND INCISION

Once the septum has been excised, the flexor-pronator muscle mass should be divided parallel to the fibers, leaving approximately a 1.5-cm span of flexor carpi ulnaris tendon attached to the epicondyle (Fig. 32-5A). The surgeon then returns the supracondylar ridge and begins elevating the anterior muscle with a Cobb elevator.

The median nerve, brachial vein, and artery are superficial to the brachialis muscle. A small cuff of fibrous tissue of the origin can be left on the supracondylar ridge as the muscle is elevated. This facilitates reattachment during closing. A proximal, transverse incision in the lacertus fibrosus may also be needed to adequately mobilize this layer of muscle.

Once the Bennett retractor is in place and the medial portion of the flexor-pronator has been incised, the plane between muscle and capsule should be carefully elevated (see Fig. 32-5B). As this plane is developed, the brachialis muscle is encountered from the underside. This muscle should be kept anterior and elevated from the capsule and anterior surface of the distal humerus. Finding this plane requires careful attention. The dissection of the capsule from the brachialis muscle proceeds both laterally and distally.

The extreme anteromedial corner of the exposure deserves special comment. In a contracture release, the anteromedial portion often requires release. To see this area, a small, narrow retractor can be inserted to retract the medial collateral ligament, pulling it medially and posteriorly. This affords visualization of the medial capsule and protection of the anterior medial collateral ligament.

The anterior capsule should be excised (see Fig. 32-5C) to the extent that that is practical and safe. When first performing this procedure, it is helpful first to incise the capsule from the medial to the lateral aspect along the anterior surface of the joint. Once this edge of the capsule is incised, it can be lifted and excised as far distally as is safe. From this vantage, and after capsule excision, the radial head and capitellum can be visualized and freed of scar, as needed.

EXPOSING AND EXCISING THE POSTERIOR CAPSULE AND BONE SPURS

The posterior capsule of the joint is exposed likewise to the anterior surface. The supracondylar ridge is again identified (see Fig. 32-5D). Using the Cobb elevator, the triceps is elevated from the posterior distal surface of the humerus. The exposure should extend far enough proximal to permit use of a Bennett retractor.

AFTERCARE

If the neurologic examination findings in the recovery room are normal, a brachial plexus block is established and maintained with a continuous pump through a percutaneous catheter.20 The arm is elevated as much as possible, and mechanical continuous passive motion exercise is begun the day of surgery and adjusted to provide as much motion as pain or the machine itself allows (see Chapter 10). After 2 days, the plexus block is discontinued, and at day 3, the continuous passive motion machine is stopped.

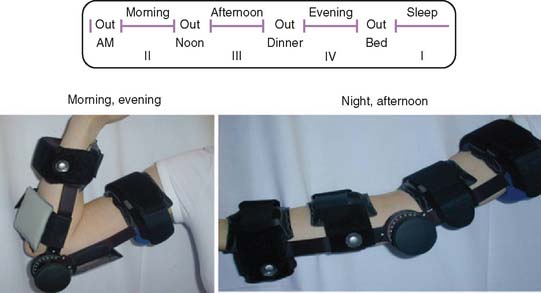

Physical therapy is not used, but a detailed program of splint therapy is prescribed. Adjustable splints are prescribed,46 depending on the motion before and after the procedure (see Chapter 11). The splints include a hyperextension or a hyperflexion brace, or both (Fig. 32-6). A detailed discussion regarding heat, ice, and anti-inflammatory medication, along with a visual schedule for bracing, is provided (see Fig. 32-6). During the first 3 months, the patient sleeps with the splint adjusted to maximize flexion or extension, whichever is more needed, and yet not to be so uncomfortable as to prevent sleeping for at least 6 hours. On rising in the morning, the patient moves the elbow actively in a tub of hot water for 15 minutes and then applies the other splint to hold the elbow at the opposite extreme of motion during the daytime. Between 8:00 in the morning and 12:00 noon, noon and 6:00 in the evening, and 6:00 in the evening and 12:00 midnight, the splint is removed for 1 hour, and the patient is encouraged to move the elbow frequently through a full range of active motion. At bedtime, if the elbow is sore from the activity, ice is applied for 10 to 15 minutes. If the elbow is stiff but notsore, heat is applied for the same period. Because the principal objective is to gain motion but to avoid pain, swelling, and inflammation, routine use of an anti-inflammatory medication is prescribed. Therapy with splints is continued for about 3 months, during which time the patient is seen at 2- to 4- week intervals, if possible. Because this is not often feasible, the patient is asked to make tracings of the upper limb with the elbow in maximum flexion and maximum extension and to send them in for review. The angles so formed are measured with a goniometer to document the patient’s progress. After 4 weeks, an arc of about 80 degrees of motion is obtained, and the amount of time that each splint is worn is gradually decreased. Splinting at night is continued for as long as 6 months if flexion contracture tends to recur when the splint is not used. Patients are advised that it may take a year to realize full correction.

RESULTS

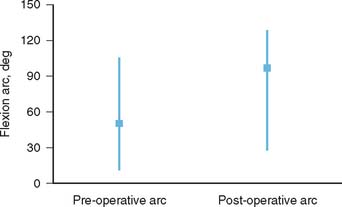

Recent reports on the results of surgical arthrolysis reveal an absolute gain in the flexion-extension arc between 30 and 60 degrees.1,10,17,26,33,43–45,59 A functional arc of motion between 30 and 130 degrees is obtained in more than 50% of cases, and some improvement in motion in more than 90% of the cases has been reported in the literature (Fig. 32-7).1,10,17,26,33,43–45,51,59 An anterior exposure popularized by Urbaniak produced good results for extrinsic stiffness, but patients with intrinsic stiffness did less well and were not considered ideal candidates for arthrolysis.59 This approach does not address disorders that limit flexion, and requires the identity and protection of the neurovascular structures. The experience was updated additionally with assessment of continuous passive motion (CPM). They concluded that the CPM did improve flexion, but did not considerably improve the amount of elbow extension after surgery.19 In Europe, a combined lateral and medial approach has been used for many years, and gains in flexion arc have averaged between 40 and 72 degrees (in approximately 400 procedures).1,10,11,17,43 Some preferred a posterior extensile approach if medial and lateral exposures are anticipated. The importance of sequential release of tissues has been emphasized based on an experience with 44 of 46 patients (95%) who were satisfied with such an approach.40 The preoperative arc improved from 45 to 99 degrees. The authors emphasize the need to release the exostosis and the collateral ligament when contracted, especially noting the need the posterior portion of the medial collateral ligament and decompress the ulnar nerve when ulnar nerve symptoms exist preoperatively.40 The outcome from different studies using a lateral approach has been gratifying. Husband and Hastings26 reported the results obtained with a lateral approach in seven patients with primarily extrinsic contractures. Range of motion (ROM) for extension contractures improved from 45 to 12 degrees and for flexion contractures from 116 to 129 degrees. The complication rate was low. A recent Scandinavian study reported that, after 5 years, range of motion was acceptable in 11 of the 13 cases.62 Using the same approach, Kessler33 observed improvement in 13 of 14 elbows. Schindler and associates55 employed a lateral approach in 30 patients and obtained a mean improvement of flexion of 35 degrees, and 30% have a normal range of motion. Using a lateral approach, Cohen and Hastings12 obtained an increase of approximately 74 degrees in 22 patients. Similarly, in 12 consecutive patients treated with a lateral exposure, the mean arc before surgery averaged 70 degrees and improved to 117 degrees after surgery, with a mean follow-up of 36 months.34 These authors added a posterior exposure to remove the capsule and osteophytes, when indicated.

FIGURE 32-7 A functional arc of rotation between 30 and 130 degrees is obtained in more than 50 percent of cases.

The Mayo Clinic experience was reported by Mansat and coworkers.39 From 1989 through 1994, 38 elbows were operated on principally for extrinsic stiffness using this limited lateral approach called the column procedure. Trauma was the cause of the contracture in 20 patients (53%). Primary osteoarthritis was responsible for the stiffness in seven patients, heterotopic ossification around the elbow secondary to head trauma or coma in five, a burn in three, congenital stiffness in two, and stiffness due to excessive immobilization after distal biceps repair in one. The mean preoperative arc of total motion was 49 degrees (range 52 to 101 degrees). At an average of 42 months of follow-up, the mean arc of total motion was 92 degrees (range 28 to 120 degrees). The total gain in flexion and extension was 43 degrees, and 33 of 38 patients (87%) enjoyed greater range of motion (Fig. 32-8). Improvement was greater in those with severe or very severe stiffness and with combined flexion-extension contractures. Extrinsic stiffness had better results on improvement of motion.

Using a medial approach, Wada and coworkers60 obtained improvement of the mean arc of movement of 64 degrees. A functional arc of flexion/extension (30 to 130 degrees) was obtained in 7 of the 14 elbows. None of the patients developed symptoms related to the ulnar nerve. According to Wada and associates, the medial approach has several advantages over both the anterior and lateral approaches. Pathologic changes in the posterior oblique bundle of the medial collateral ligament can be observed and excised under direct vision. Anterior and posterior exposure is possible through one medial incision, through which a complete soft tissue release and excision of part of the olecranon and coronoid process can be undertaken if necessary. Additional lateral exposure is indicated only if the medial approach has proved to be inadequate.60 In the medial approach, the ulnar nerve is routinely released and protected under direct vision which decreases the risk of damage.

NERVE PALSIES

A most important emerging consideration of the proper treatment of the elbow stiffness is the vulnerability of the ulnar nerve. The most common cause of failure of treatment has been those patients in whom the preoperative ulnar nerve symptoms were not appreciated or addressed, or those patients in whom ulnar nerve symptoms developed postoperatively without adequate treatment. This is attributed to traction neuritis caused by the abrupt increase in elbow flexion during the operation. Even in the absence of preoperative neurologic symptoms, the nerve may be compromised subclinically and becomes symptomatic as elbow flexion increases after surgery. Therefore, all patients who have stiff elbows must be evaluated for the presence or absence of ulnar nerve symptoms. Antuna and colleagues3 recommended that elbows with preoperative flexion limited to 90 to 100 degrees in which we expect to improve the motion by 30 or 40 degrees must be treated with inspection and often prophylactic decompression or translocation of the nerve depending on the appearance of the nerve once the surgical procedure is finished. Furthermore, all patients with preoperative ulnar-nerve symptoms, even if they are mild, are treated with mobilization of the nerve. Manipulation of the elbow in the early postoperative period must be avoided if the nerve has not been decompressed or translocated. In our series, we found that about 10% of patients have dysfunction of the nerve after release. Most of these problems resolve over a period of days or weeks. The radial nerve is also vulnerable, especially if excessive retraction is applied through the lateral approach. The other point of vulnerability is distal at the level of the posterior interosseous nerve.39

COMPLICATIONS

In our study,39 complications occurred in 4 of 38 elbows (10%): two cases of intra-articular bleeding, one of which impaired the final outcome; and two transient paresthesias of the ulnar nerve, both of which resolved spontaneously. The typical complication is loss of motion after surgery. Loss of the flexion arc after a period of improvement was seen in 10 patients (26%). Four patients ultimately lost the benefits of the procedure and, on average, had 25 degrees’ less motion than before surgery. The same amount of decreased ROM between the immediate postoperative ROM and the ROM measured at follow-up were reported in the literature. In Cikes’ study, the patients decreased their ROM in flexion-extension by 7.77 degrees (range, −35 to 0 degrees).11 Chantelot reported an average decrease between 5 and 15 degrees compared with the mobility obtained just after surgery.10

1 Allieu Y. Raideurs et arthrolyses du coude. Rev. Chir. Orthop. 1989;75(suppl I):156.

2 Amadio P.C., Dobyns J.H. Congenital abnormalities of the elbow. In: Morrey B.F., editor. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2000:165.

3 Antuna S.A., Morrey B.F., Adams R.A., O’Driscoll S.W. Ulnohumeral arthroplasty for primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow. Long-term outcome and complications. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84A:2168.

4 Balay B., Setiey L., Vidalain J.P. Les raideurs du coude. Traitement orthopédique et chirurgical. Acta Orthop. Belg. 1975;41:414.

5 Ball C.M., Meunier M., Galatz L.M., Calfee R., Yamaguchi K. Arthroscopic treatment of post-traumatic elbow contracture. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:624.

6 Bonutti P.M., Windau J.E., Ables B.A., Miller B.G. Static progressive, stretch to reestablish elbow range of motion. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1994;303:128.

7 Breen T.F., Gelberman R.H., Ackerman G.N. Elbow flexion contractures: treatment by anterior release and continuous passive motion. J. Hand Surg. 1988;13B:286.

8 Buxton J.D. Ossification in the ligaments of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1938;20:709.

9 Cauchoix J., Deburge A. L’Arthrolyse du coude dans les raideurs post traumatiques. Acta Orthop. Belg. 1975;41:385.

10 Chantelot C., Fontaine C., Migaud H., Remy F., Chapnikoff D., Duquennoy A. Etude retrospective de 23 arthrolyses du coude pour raideur post-traumatique: facteurs prédictifs du résultat. Rev. Chir. Orthop. 1999;85:823.

11 Cikes A., Jolles B.M., Farron A. Open elbow arthrolysis for posttraumatic elbow stiffness. J. Orthop. Trauma. 2006;20:405.

12 Cohen M.S., Hastings H.II. Posttraumatic contracture of the elbow: Operative release using a lateral collateral ligament sparing approach. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80B:805.

13 Dickson R.A. Reversed dynamic slings. A new concept in the treatment of posttraumatic elbow flexion contractures. Injury. 1976;8:35.

14 Dietrich S.L. Rehabilitation and nonsurgical management of musculoskeletal problems in the hemophilic patients. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1975;240:328.

15 Doornberg J.N., Ring D., Jupiter J.B. Static progressive splinting for posttraumatic elbow stiffness. J. Orthop. Trauma. 2006;20:400.

16 Duke J.B., Tessler R.H., Dell P.C. Manipulation of the stiff elbow with patient under anesthesia. J. Hand Surg. 1991;16A:19.

17 Esteve P., Valentin P., Deburge A., Kerboull M. Raideurs et ankyloses post-traumatiques du coude. Rev. Chir. Orthop. 1971;57(suppl I):25.

18 Garland D.E., O’Hollarin R.M. Fractures and dislocations about the elbow in the head injury adult. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1982;168:38.

19 Gates H.S., Sullivan R.N., Urbaniak J.R. Anterior capsulotomy and continuous passive motion in the treatment of post-traumatic flexion contracture of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74A:1229.

20 Gaumann D.M., Lennon R.L., Wedel D.J. Continuous axillary block for postoperative pain management. Reg. Anesth. 1988;13:77.

21 Gelinas J.J., Faber K.J., Patterson S.D., King G.J.W. The effectiveness of turnbuckle splinting for elbow contractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82B:74.

22 Glynn J.J., Niebauer J.J. Flexion and extension contracture of the elbow. Surgical management. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1976;117:289.

23 Green D.P., McCoy H. Turnbuckle orthotic correction of elbow-flexion contractures after acute injuries. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1979;61A:1092.

24 Gutierrez L.S. A contribution to the study of the limiting factors of elbow extension. Acta Anat. 1964;56:146.

25 Hildebrand K.A., Zhang M., Hart D.A. High rate of joint capsule matrix turnover in chronic human elbow contractures. Clin. Orthop. 2005;439:228.

26 Husband J.B., Hastings H. The lateral approach for operative release of post-traumatic contracture of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:1353.

27 Itoh Y., Saegusa K., Ishiguro T., Horiuchi Y., Sasaki T., Uchinishi K. Operation for the stiff elbow. Int. Orthop. 1989;13:263.

28 Johanson O. Capsular and ligament injuries of the elbow joint: clinical and arthrographic study. Acta Chir. Scand. 1962;287(suppl):124.

29 Jones G.S., Savoie F.H.III. Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:277.

30 Josefsson P.O., Johnell O., Gentz C.F. Long-term sequelae of simple dislocation of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66A:927.

31 Judet J., Judet H. Arthrolyse du coude. Acta Orthop. Belg. 1975;41:412.

32 Kerboull M. Le traitement des raideurs du coude de l’adulte. Acta Orthop. Belg. 1975;41:438.

33 Kessler I. Arthrolysis of the elbow. In: Kashiwagi D., editor. Elbow Joint, Proceedings of the International Seminar, Kobe, Japan. International Congress, Series 678. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica; 1985:77.

34 Kraushaar B.S., Nirschl R.P., Cow W. A modified lateral approach for release of posttraumatic elbow contracture. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:476.

35 Kim S.J., Shin S.J. Arthroscopy treatment for limitation of motion of the elbow. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2000;375:140.

36 Loomis J.K. Reduction and after-treatment of posterior dislocation of the elbow: with special attention to the brachialis muscle and myositis ossificans. Am. J. Surg. 1944;63:56.

37 Lusskin R., Grynbaum B.B., Dhir R.S. Rehabilitation surgery in adult spastic hemiplegia. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1969;63:132.

38 MacKay-Lyons M. Low-load, prolonged stretch in treatment of elbow flexion contractures secondary to head trauma: a case report. Phys. Ther. 1989;69:292.

39 Mansat P., Morrey B.F. The “column procedure”: a limited surgical approach for the treatment of stiff elbows. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80A:1603.

40 Marti R.H., Kerkhoffs G.M., Maas M., Blankevoort L. Progressive surgical release of a posttraumatic stiff elbow. Technique and outcome after 2-18 years in 46 patients. Acta Orthop. Scand. 2002;73:144.

41 Mehlhoff T.L., Noble P.C., Bennett J.B., Tullos H.S. Simple dislocation of the elbow in the adult. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70A:244.

42 Mendelson L., Grosswassner Z., Najenson T., Sandbank U., Solzi P. Periarticular new bone formation in patients suffering from severe head injuries. Scand. J. Rehab. Med. 1975-1976;7:141.

43 Merle D’Aubigne R., Kerboul M. Les opérations mobilisatrices des raideurs et ankylose du coude. Rev. Chir. Orthop. 1966;52:427.

44 Morrey B.F. Surgical takedown of the ankylosed elbow. Orthop. Trans. 1988;12:734.

45 Morrey B.F. Post-traumatic contracture of the elbow. Operative treatment, including distraction arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:601.

46 Morrey B.F. Splints and bracing at the elbow. In: Morrey B.F., editor. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 2000:150.

47 Morrey B.F. The posttraumatic stiff elbow. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2005;431:26.

48 Morrey B.F., An K.N. Functional evaluation of the elbow. In: Morrey B.F., editor. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 2000:74.

49 Nowicki K.D., Shall L.M. Arthroscopic release of a posttraumatic flexion contracture in the elbow: a case report and review of the literature. Arthroscopy. 1992;8:544.

50 Oh I., Smith J.A., Spencer G.E.Jr, Frankel V.H., Mack R.P. Fibrous contracture of muscles following intramuscular injections in adults. Clin. Orthop. 1977;127:214.

51 Park M.J., Kim H.G., Lee J.Y. Surgical treatment of post-traumatic stiffness of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86B:1158.

52 Phillips B.B., Strasburger G. Arthroscopic treatment of arthrofibrosis of the elbow joint. Arthroscopy. 1998;14:38.

53 Richards R.R., Beaton D., Bechard M. Restoration of elbow motion by anterior capsular release of post-traumatic flexion contractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73B(suppl II):107.

54 Savoie F.H.III, Nunley P.D., Field L.D. Arthroscopic management of the arthritic elbow: indications, techni-que and results. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:214.

55 Schindler A., Yaffe B., Chetrit A., Modan M., Engel J. Factors influencing elbow arthrolysis. Ann. Chir. Main Memb. Super. 1991;10:237.

56 Seth M.K., Khurana J.K. Bony ankylosis of the elbow after burns. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1985;67B:747.

57 Timmerman L.A., Andrews J.R. Arthroscopic treatment of posttraumatic elbow pain and stiffness. Am. J. Sports Med. 1994;22:230.

58 Tsuge K., Mizuseki T. Débridement arthroplasty for advanced primary osteoarthritis of the elbow. Results of a new technique used for. 29 elbows. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 1994;76B:641.

59 Urbaniak J.R., Hansen P.E., Beissinger S.F., Aitken M.S. Correction of post-traumatic flexion contracture of the elbow by anterior capsulotomy. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1985;67A:1160.

60 Wada T., Ishii S., Usui M., Miyano S. The medial approach for operative release of post-traumatic contracture of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82B:68.

61 Weiss A.P.C., Sachar K. Soft tissue contractures about the elbow. Hand Clin. 1994;10:439.

62 Weizenbluth M., Eichenblat M., Lipskeir E., Kesslser I. Arthrolysis of the elbow: 13 cases of post-traumatic stiffness. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1989;60:642.

63 Willner P. Anterior capsulectomy for contractures of the elbow. J. Int. Coll. Surg. 1948;11:359.

64 Wilson P.D. Capsulectomy for the relief of flexion contractures of the elbow following fracture. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1944;26A:71.

65 Wheeler D.K., Linscheid R.L. Fracture-dislocations of the elbow. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1967;50:95.