21 Exploring New Frontiers

Endovascular Treatment of the Occluded ICA

Introduction

Surgical revascularization of the occluded extracranial carotid artery has been established as a potential therapy in selected patients.1 However, this procedure has not been widely applied because its intrinsic risks and the questionable benefits. Endovascular revascularization of acutely and chronically occluded femoral and coronary arteries has been performed for some time with good degree of clinical and radiological success. Application of these techniques to the extracranial carotid and vertebral arteries has lagged behind for fear of dislodging emboli. With advances in endovascular techniques, increasing experience with angioplasty and stenting of large extracranial cervical vessels, and the availability of a variety of distal protection devices, several operators have reported their results following endovascular revascularization of the acutely or even chronically occluded internal carotid artery (ICA).2–20 In this chapter, we provide an overview of the rationale, techniques, results, and complications of endovascular revascularization of acute and chronic occlusion of the extracranial ICA.

Acute carotid occlusion

Management of patients with stroke caused by acute ICA occlusion is challenging. Medical therapy alone is associated with a high rate of permanent severe neurological disability and mortality.1 In patients with acute stroke and ICA occlusion, early restoration of flow in the occluded ICA may prevent further worsening, improve symptoms, and reduce the risk of recurrent stroke.2 Currently, the invasive treatment of patients with acute ICA occlusion is not standardized. Acute ICA occlusion responds poorly to intravenous thrombolysis alone or in combination with intra-arterial pharmacological thrombolysis with recanalization rates ranging from 10%21 to 50%,22–24 and resultant mortality of 50%.21–24 Slightly better clinical results have been reported following mechanical thrombectomy, but only a few reports are available.25,26

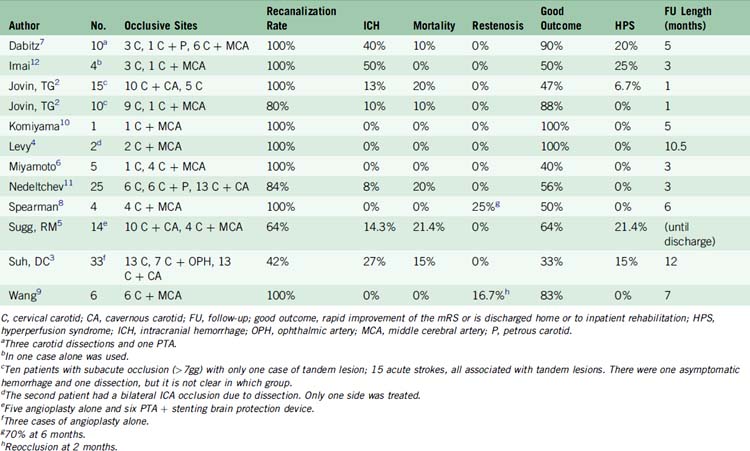

Over the past decade, several authors2,3–11,27 have reported the feasibility of endovascular revascularization of the acutely occluded internal carotid artery with angioplasty and stenting with higher rates of recanalization and clinical improvement than reported with other methods (Table 21–1).

Technique

Symptomatic acute thrombosis of the proximal ICA often occurs in concomitance with ICA bifurcation (T-lesion) or MCA occlusion. The natural history of associated proximal ICA and central distal occlusions is poor.2,3–10,12 Acute revascularization of the proximal ICA in such cases allows catheterization and thrombolysis of the distal segment and, by increasing distal flow, improves the chances of maintaining vessel patency after successful distal thrombolysis. In addition, stenting of the occluded ICA may “trap” thrombus against the carotid wall, potentially decreasing the risk of delayed distal emboli.

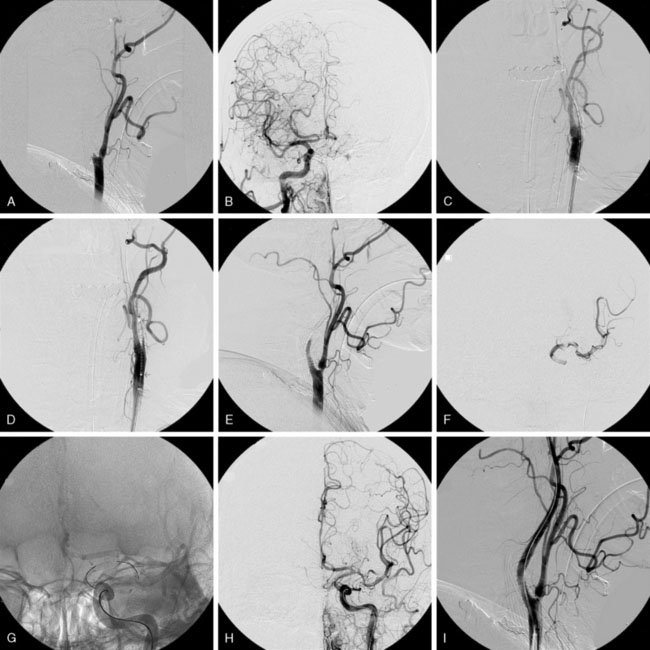

At the completion of the procedure, strict blood pressure control is maintained in those patients with successful recanalization (systolic pressure below 160 mm Hg in patients with acute occlusions or below 140 mm Hg when the occlusion is subacute or chronic). Clopidogrel is continued for 30 days and aspirin indefinitely. A head CT scan is routinely performed the following morning to rule out hemorrhage and to assess the extent of the infarcted area (Figure 21–1).

Results and Complications

Over the past 10 years, several authors have detailed their results with revascularization of the acutely occluded ICA. Nedeltchev and coworkers11 studied 56 consecutive patients who suffered an MCA stroke following ICA occlusion between 1997 and 2003. Twenty-five of these patients underwent attempted endovascular revascularization (endovascular group), while 31 patients received medical treatment consisting of antiplatelet medications and, in some cases, heparin therapy (medical group). Recanalization of the ICA was achieved in 84% of patients in the endovascular group with a combination of thrombo-aspiration through an 8-French guide-catheter and stent deployment in the occluded ICA. Recanalization of the coexistent MCA occlusion (TIMI grade 2 and 3) was obtained in 52% of these patients. In the endovascular group, outcome at 3 months was favorable (modified Rankin score of 0–2) in 56% of patients and unfavorable in 24%. Twenty percent of patients died. In the medically treated group, a favorable outcome was observed in only 26% of patients. This series stresses the importance of recanalization of the coexistent distal occlusion since MCA recanalization was the only predictor of good outcome. Symptomatic hemorrhage occurred in 8%. Although concerns exist regarding the risk of dissection and vessel perforation during blind “probing” of the occluded segment, these complications were not observed in this series.

Jovin and collaborators2 reported a series of 23 patients who underwent successful ICA revascularization (in two additional patients crossing of the occlusion was not possible and no stent could be deployed). Of these 23 patients, 15 were revascularized within the time window for acute stroke therapy while the remaining eight had suffered subacute ICA occlusion and demonstrated ongoing symptoms related to hemodynamic compromise. A good outcome at 30 days was reported in five patients (33%) with acute ICA occlusion. Four of the five patients experiencing a good outcome did not have a coexistent intracranial occlusion and the fifth one had a coexistent MCA occlusion that was revascularized with pharmacological intra-arterial thrombolysis. No patient who had a tandem occlusion that did not revascularize achieved a good outcome. Complications related to the endovascular procedure included one asymptomatic hemorrhage and one dissection of the ICA without flow compromise. No serious complications were observed in the eight patients who had received IV tPA in conjunction with endovascular revascularization indicating the feasibility and safety of this approach. Table 21–1 provides a comprehensive summary of results and complications after revascularization of acute ICA occlusion.

Chronic carotid occlusion

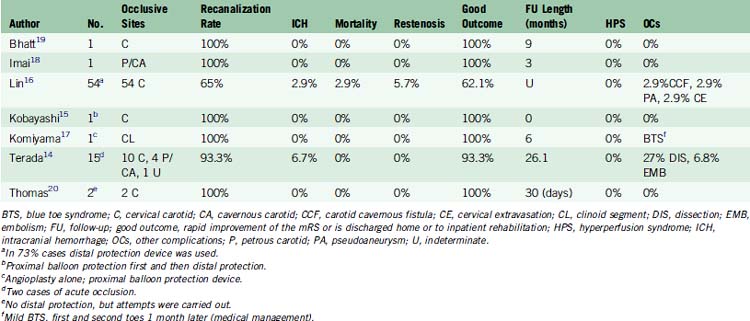

Endovascular revascularization of chronically occluded femoral, subclavian, and coronary arteries is an established practice in selected patients. In 2005, Terada et al.28 reported the first patient with chronic carotid occlusion who underwent successful endovascular revascularization with flow reversal. Two years later, Kao and coworkers,13 using a technique utilized to reopen occluded coronary arteries, reported the first series of 30 patients with chronic carotid occlusion who underwent attempted endovascular revascularization. Following these early reports, several other authors have reported successful recanalization of the chronically occluded ICA (Table 21–2).

Potential candidates for revascularization of chronic ICA occlusion must fulfill the following criteria:13–15 (1) hemodynamic symptoms ascribed to the occluded territory, (2) hemodynamic failure demonstrated by perfusion studies, and (3) angiographic demonstration of a relatively short occluded segment.14 This last angiographic requirement can be difficult to evaluate. Careful analysis of the angiograms with assessment of late retrograde filling of the ICA segment distal to the occlusion through collateral circulation is of critical importance to select patients who may benefit from endovascular recanalization. Assessment of the extent of occlusion can be difficult with other noninvasive angiographic techniques such as CTA and MRA, although dynamic CTA can offer valuable information.

Techniques

Technical pitfalls of chronic ICA occlusion recanalization are related primarily to crossing the occlusion while avoiding dislodgment of distal emboli.29–31 Various techniques have been described to circumvent these problems and minimize the risk of distal emboli.

The availability of “protection devices” has increased the safety of recanalization of the occluded ICA. Four types of “protection devices” are available for use in the extracranial carotid: distal occlusion balloon, distal filter, proximal occlusion catheter, and the Parodi’s device.32,33 The main disadvantage of the first two is the need to cross the lesions before device deployment with the consequent risk of cerebral microembolization before distal protection is established.34–36

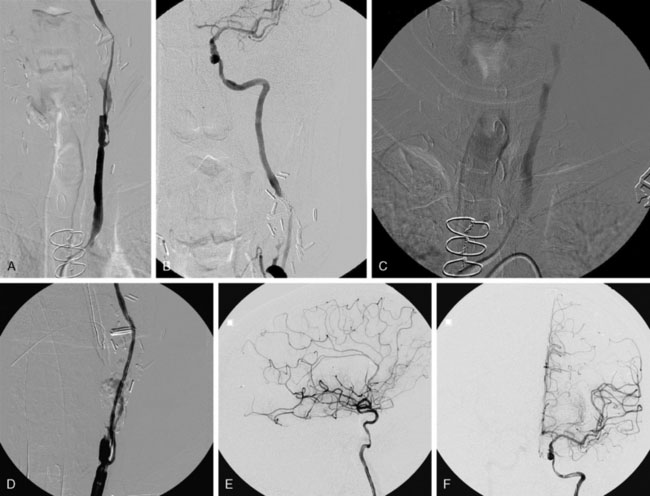

Proximal occlusion can be achieved with one of two methods. One of these methods involves obtaining proximal occlusion with a double lumen balloon catheter positioned and inflated in the common carotid artery proximal to the occlusion. The inner lumen of the balloon allows passage of devices while the balloon is inflated though the other lumen. The goal of proximal occlusion is to prevent anterograde flow to dislodge emboli during and immediately after revascularization. Proximal common carotid occlusion alone is insufficient to prevent particles from embolizing to the brain37 because of collateral vessels from the external carotid artery. In cases where the external carotid artery is patent, a separate small (5F) guide-catheter can be placed in the common carotid artery to allow passage of a small compliant balloon that can be separately inflated into the external carotid artery.

The other method by which proximal occlusion can be achieved is the Parodi Anti-Embolization Catheter (PAEC). This is an ingenious device originally designed to allow flow reversal during angioplasty and stenting of carotid stenosis. It consists of a triple lumen-guiding catheter with an occlusion balloon at the distal end. This balloon has a teardrop shape to prevent any dead space between the orifice of the catheter and the occlusion balloon. Occlusion of the common carotid artery is achieved by inflating this balloon while access to the lesion is possible through the main inner lumen. The main lumen has an inner diameter of 7F that allows for navigation of balloons and stents. The main lumen is connected to a three-way Y-adapter at its proximal end so that one has access to the lesion through the main lumen while suction is applied or reversal of flow is created through the other ports. In addition, the extra side port can be used for the insertion of an external carotid artery occlusion balloon, if one is needed.33 The Parodi device also allows for activation of an arteriovenous fistula through connection with the femoral vein and this allows true flow reversal.33

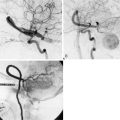

If distal protection is used instead of proximal flow arrest, then a guide-catheter of sufficient internal diameter to allow for passage of multiple devices if needed is placed into the common carotid proximally to the occlusion (Figure 21–2).

Crossing the lesion

A microcatheter and microguidewire (0.016 inch or 0.014 inch) are typically used to cross the occluded ICA. The microcatheter is parked immediately proximal to the occlusion to provide backup support to the microguidewire as it is passed through the occluded segment. A tapered-tip stiff 0.014-inch guidewire specifically designed to cross coronary occlusions can be particularly helpful in this phase.13 Care must be paid to avoid too much torquing or “drilling” of the microcatheter during this phase to avoid entering a false lumen with the risk of dissection or perforation. It is often difficult or even impossible to cross the occluded segment with the microguidewire. Resistance to passage of the microguidewire can be used as a criterion to judge the length and location of the occlusion.14 Often, if the microguidewire does not cross the occluded segment, it is necessary to use a 0.035 guidewire to penetrate the occluded portion. In such cases, a 4F catheter can be passed through the occlusion over the 0.035 guidewire to gently “dilate” the channel. The guidewire is gently advanced while making sure that the microguidewire is within the true lumen of the vessel on orthogonal projections. At this point the microcatheter can be advanced distal to the occlusion and a gentle injection can be performed to confirm position into the true lumen and confirm patency of the ICA segment distal to the occlusion.

Proximal Occlusion Technique

Results and complications

Recently, Lin et al.16 updated their original experience and reported their results in 54 patients who underwent revascularization for chronic ICA occlusion. Revascularization was achieved in 63% of patients. Distal protection devices were used in 73% of cases. In 10 patients, the use of distal embolic protection devices was not possible because of small distal vessel diameter. In the patients in whom technical success was achieved, the residual stenosis was 9%. The combined morbidity and mortality at 3 months was 4%. Vascular complications included an iatrogenic carotid-cavernous fistula, a delayed cervical ICA pseudoaneurysm, and extravasation of contrast in the neck during attempted crossing of ICA occlusion.

In 2009, Terada and coworkers14 reported a series of 14 patients with a total of 15 occluded ICAs who underwent endovascular revascularization using the proximal occlusion technique and flow reversal. All of the patients were suffering from hemodynamic symptoms refractory to medical therapy. They reported a technical success rate of 93% (14 out of 15 occlusions). Revascularized occlusions involved the cervical ICA in 10 cases and the petrous or cavernous portions of the artery in the remaining four. Complications included one case of distal MCA branch occlusion without clinical sequelae and one SAH due to microwire perforation of an MCA branch. No patient suffered recurrent symptoms at a mean follow up of 26.1 months. No cases of clinical hyperperfusion were observed.

Restenosis of the revascularized segment is a potential concern. However, experience in other vascular territories suggests that the risk of restenosis after revascularization of an occluded artery is higher in the coronary circulation38 than in the iliac and subclavian arteries.39,40 This observation would suggest that restenosis may be lower if the vessel diameter is greater than 3 mm. In this respect, the restenosis rate should be lower in the ICA and the largest series reported so far confirm this supposition as no restenosis >50% was observed by Terada and coworkers in their 14 cases,14 while Kao and coworkers reported a restenosis rate of 13.6%.13

Cerebrovascular autoregulation in regions with chronic ischemia may be defective, and a sudden increase of perfusion after revascularization of chronic ICA occlusion raises concerns for hyperperfusion syndrome. Strict control of blood pressure after endovascular recanalization is critical to prevent or minimize the effects of this complication. Surprisingly, according to the literature, no cases of hyperperfusion syndrome were detected after revascularization of chronic ICA occlusion.14–17,20 A summary of results and complications in published series of ICA occlusion is shown in Table 21–2.

1 Meyer F.B., Sundt T.M., Piepgras D.G., et al. Emergency carotid endarterectomy for patients with acute carotid occlusion and profound neurological deficits. Ann Surg. 1986;203:82-89.

2 Jovin T.G., Gupta R., Uchino K., et al. Emergent stenting of extracranial internal carotid artery occlusion in acute stroke has a high revascularization rate. Stroke. 2005;36:2426-2430.

3 Suh D.C., Kim J.K., Choi C.G., et al. Prognostic factors for neurologic outcome after endovascular revascularization of acute symptomatic occlusion of the internal carotid artery. Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1167-1171.

4 Levy D.I. Endovascular treatment of carotid artery occlusion in progressive stroke syndromes: technical note. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:186-191. discussion 91-3

5 Sugg R.M., Malkoff M.D., Noser E.A., et al. Endovascular recanalization of internal carotid artery occlusion in acute ischemic stroke. Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:2591-2594.

6 Miyamoto N., Naito I., Takatama S., et al. Urgent stenting for patients with acute stroke due to atherosclerotic occlusive lesions of the cervical internal carotid artery. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2008;48:49-55. discussion 56

7 Dabitz R., Triebe S., Leppmeier U., et al. Percutaneous recanalization of acute internal carotid artery occlusions in patients with severe stroke. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:34-41.

8 Spearman M.P., Jungreis C.A., Wechsler L.R. Angioplasty of the occluded internal carotid artery. Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1791-1796. discussion 1797-9

9 Wang H., Lanzino G., Fraser K., et al. Urgent endovascular treatment of acute symptomatic occlusion of the cervical internal carotid artery. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:972-977.

10 Komiyama M., Nishio A., Nishijima Y. Endovascular treatment of acute thrombotic occlusion of the cervical internal carotid artery associated with embolic occlusion of the middle cerebral artery: case report. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:359-363. discussion 63-4

11 Nedeltchev K., Brekenfeld C., Remonda L., et al. Internal carotid artery stent implantation in 25 patients with acute stroke: preliminary results. Radiology. 2005;237:1029-1037.

12 Imai K., Mori T., Izumoto H., et al. Emergency carotid artery stent placement in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1249-1258.

13 Kao H.L., Lin M.S., Wang C.S., et al. Feasibility of endovascular recanalization for symptomatic cervical internal carotid artery occlusion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:765-771.

14 Terada T., Okada H., Nanto M., et al. Endovascular recanalization of the completely occluded internal carotid artery using a flow reversal system at the subacute to chronic stage. J Neurosurg. 2010;112(3):563-571.

15 Kobayashi N., Miyachi S., Hattori K., et al. Carotid angioplasty with stenting for chronic internal carotid artery occlusion: technical note. Neuroradiology. 2006;48:847-851.

16 Lin M.S., Lin L.C., Li H.Y., et al. Procedural Safety and Potential Vascular Complication of Endovascular Recanalization for Chronic Cervical Internal Carotid Artery Occlusion. Circ Cardiovasc Interventions. 2008;1:119-125.

17 Komiyama M., Yoshimura M., Honnda Y., et al. Percutaneous angioplasty of a chronic total occlusion of the intracranial internal carotid artery. Case report. Surg Neurol. 2006;66:513-518. discussion 518

18 Imai K., Mori T., Izumoto H., et al. Successful stenting seven days after atherothrombotic occlusion of the intracranial internal carotid artery. J Endovasc Ther. 2006;13:254-259.

19 Bhatt A., Majid A., Kassab M., et al. Chronic total symptomatic carotid artery occlusion treated successfully with stenting and angioplasty. J Neuroimaging. 2009;19:68-71.

20 Thomas A.J., Gupta R., Tayal A.H., et al. Stenting and angioplasty of the symptomatic chronically occluded carotid artery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:168-171.

21 Christou I., Felberg R.A., Demchuk A.M., et al. Intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and flow improvement in acute ischemic stroke patients with internal carotid artery occlusion. J Neuroimaging. 2002;12:119-123.

22 Zaidat O.O., Suarez J.I., Santillan C., et al. Response to intra-arterial and combined intravenous and intra-arterial thrombolytic therapy in patients with distal internal carotid artery occlusion. Stroke. 2002;33:1821-1826.

23 Linfante I., Llinas R.H., Selim M., et al. Clinical and vascular outcome in internal carotid artery versus middle cerebral artery occlusions after intravenous tissue plasminogen activator. Stroke. 2002;33:2066-2071.

24 Arnold M., Nedeltchev K., Mattle H.P., et al. Intra-arterial thrombolysis in 24 consecutive patients with internal carotid artery T occlusions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:739-742.

25 Flint A.C., Duckwiler G.R., Budzik R.F., et al. Mechanical thrombectomy of intracranial internal carotid occlusion: pooled results of the MERCI and Multi MERCI Part I trials. Stroke. 2007;38:1274-1280.

26 Smith W.S., Sung G., Saver J., et al. Mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: final results of the Multi MERCI trial. Stroke. 2008;39:1205-1212.

27 Meves S.H., Muhs A., Federlein J., et al. Recanalization of acute symptomatic occlusions of the internal carotid artery. J Neurol. 2002;249:188-192.

28 Terada T., Yamaga H., Tsumoto T., et al. Use of an embolic protection system during endovascular recanalization of a totally occluded cervical internal carotid artery at the chronic stage. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:558-564.

29 Ackerstaff R.G., Moons K.G., van de Vlasakker C.J., et al. Association of intraoperative transcranial doppler monitoring variables with stroke from carotid endarterectomy. Stroke. 2000;31:1817-1823.

30 Jordan W.D., Voellinger D.C., Doblar D.D., et al. Microemboli detected by transcranial Doppler monitoring in patients during carotid angioplasty versus carotid endarterectomy. Cardiovasc Surg (London). 1999;7:33-38.

31 Coggia M., Goeau-Brissonniere O., Duval J.L., et al. Embolic risk of the different stages of carotid bifurcation balloon angioplasty: an experimental study. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31:550-557.

32 Parodi J.C., La Mura R., Ferreira L.M., et al. Initial evaluation of carotid angioplasty and stenting with three different cerebral protection devices. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32:1127-1136.

33 Ohki T., Parodi J., Veith F.J., et al. Efficacy of a proximal occlusion catheter with reversal of flow in the prevention of embolic events during carotid artery stenting: an experimental analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:504-509.

34 Cremonesi A., Manetti R., Setacci F., et al. Protected carotid stenting: clinical advantages and complications of embolic protection devices in 442 consecutive patients. Stroke. 2003;34:1936-1941.

35 Eckert B., Zeumer H. Editorial comment—carotid artery stenting with or without protection devices? Strong opinions, poor evidence!. Stroke. 2003;34:1941-1943.

36 Terada T., Tsuura M., Matsumoto H., et al. Results of endovascular treatment of internal carotid artery stenoses with a newly developed balloon protection catheter. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:617-623. discussion 623-5

37 Theron J. Cerebral protection during carotid angioplasty. J Endovasc Surg. 1996;3:484-486.

38 Antoniucci D., Valenti R., Santoro G.M., et al. Restenosis after coronary stenting in current clinical practice. Am Heart J. 1998;135:510-518.

39 Duber C., Klose K.J., Kopp H., et al. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for occlusion of the subclavian artery: short- and long-term results. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1992;15:205-210.

40 Mathias K.D., Luth I., Haarmann P. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty of proximal subclavian artery occlusions. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1993;16:214-218.