chapter 9 Exercise as therapy

WHY IS EXERCISE ESSENTIAL FOR HEALTH?

The renowned exercise biologist, Professor Frank Booth, described in great detail the importance of exercise for maintaining normal function and health, in his extensive review of the research literature.1 The basic tenet is that the human genome has not changed appreciably in the past 45,000 years and developed in an environment of high levels of physical activity. While our lifestyles have become predominantly sedentary in our working and leisure environments, our underlying biology expects stimuli involving physical work for extended periods, possibly dawn until dusk, as well as high-force and high-power activities such as would have been required to carry water, children, food, construction materials and tools as well as to run after animals that we sought to kill, or run away from animals desiring to eat us.

EXERCISE TRENDS IN AUSTRALIA AND ELSEWHERE

Despite the strong research evidence indicating that regular physical exercise is essential for human health, rates of sedentary and low exercise levels in Australia remain very high, at around 70% of the population over 15 years of age.2 This has not changed appreciably in the past 10 years despite the best efforts of government and organisations such as the Cancer Council and Heart Foundation to address this societal problem. The rate of no or low physical exercise is higher in females (73%) than in males (66%), and higher in the oldest age group of 75 years and over, at 83%. The rate is lowest in people aged 15–24 years but still frighteningly high at 62%.

The 2007 Australian National Children’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey is one of the most extensive investigations of exercise patterns in children aged 2–16 years conducted to date, with some 4487 participants. It was encouraging that most children aged 9–16 years met the Department of Health and Ageing recommendation that children aged 5–18 years accumulate at least 60 minutes, and up to several hours, of moderate to vigorous physical activity every day. According to the survey, there was a 69% chance that any given child would achieve this recommendation. With regard to gender, girls met the guidelines less frequently than boys, both boys and girls were less likely to meet the requirement as they got older, and this drop-off was much higher in older girls.3

GENERAL HEALTH, QUALITY OF LIFE AND LONGEVITY

The application of exercise for prevention and management of some specific health problems will be described later in this chapter. To establish the importance of exercise for general health, quality and quantity of life, the overall effects of exercise are summarised in Table 9.1.

| Health parameter | Effect of regular exercise | Preferred exercise mode |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | Reduction of systolic and diastolic blood pressure | Aerobic predominantly but some research indicates anabolic also effective |

| Cardiac function | Increased stroke volume and maximum cardiac output | Aerobic exercise |

| Cardiorespiratory fitness | Increased efficiency and maximum capacity | Aerobic exercise |

| Haemoglobin | Increased | Aerobic exercise |

| Cholesterol | Reduces LDL, elevates HDL, lowers total cholesterol and triglycerides | Aerobic exercise |

| Glucose metabolism | Glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity improved | Aerobic and anabolic exercise |

| Bone density | Increased bone mineral density, bone mineral content, cortical thickness and fracture threshold | Anabolic and ground-based impact exercises (e.g. skipping, bounding, jumping) |

| Body fat | Reduced percentage body fat | Aerobic and anabolic combined |

| Muscle mass | Increased muscle cross-sectional area, increased fibre size | Anabolic exercise |

| Strength | Increased | Anabolic exercise |

| Physical functioning | Gait speed, stair climb, sit to stand, balance, falls risk all improved | Anabolic and aerobic exercise |

| Quality of life | Improvement in both general and disease-specific QOL measures | Anabolic and aerobic exercise |

HDL: high-density lipoprotein; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; QOL: quality of life.

TYPES OF EXERCISE

AEROBIC EXERCISE

Cardiorespiratory capacity or fitness relates to the ability to perform large-muscle-group, dynamic, moderate-to-high intensity exercise such as walking or cycling for prolonged periods.4 Exercise prescription for cardiovascular fitness is based on mode, intensity, duration and frequency of the activity. The activities prescribed most frequently are walking, cycling, jogging, running, rowing, swimming and hiking. It is suggested that individuals should choose activities that they enjoy and are enthusiastic about continuing, as this will increase program compliance.

ANABOLIC EXERCISE

The other major form of exercise critical to long-term health is anabolic exercise, which is also termed ‘resistance training’ or ‘weightlifting’. This form of exercise involves performing movements against resistance such as barbells, dumbbells, resistance machines or elastic resistance, such that the number of repetitions that can be completed is limited to 12 or less. This is a very important stipulation of intensity. If the movement can be completed more than 10–12 times then the resistance is too light and must be increased. Without such resistance the positive anabolic effects on muscle and bone will not be realised and the hormonal changes that are so neuro-protective will not result.

This concept may seem a little ‘out there’ for people who have not exercised previously or even lifted weights before but the research evidence in support of regular anabolic exercise is huge, demonstrating marked improvements in muscle mass, bone strength, functional capacity and positive effects on mental health and cognitive function. The recommendation of the American College of Sports Medicine is for people aged over 65 years to complete resistance training two to three times per week. The precise prescription is presented in Boxes 9.1 and 9.2.

Do moderately intense aerobic exercise 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week

Do vigorously intense aerobic exercise 20 minutes a day, 3 days a week

Do 8–10 strength-training exercises, 10–15 repetitions of each exercise 2–3 times per week

If you are at risk of falling, perform balance exercises

Source: Nelson et al 20065

BOX 9.2 Physical activity guidelines for healthy adults under 65 years

Do moderately intense cardio 30 minutes a day, 5 days a week

Do vigorously intense cardio 20 minutes a day, 3 days a week

Do 8–10 strength-training exercises, 8–12 repetitions of each exercise, twice a week

Source: Haskell et al 20076

For healthy adults over age 65 or adults aged 50–64 with chronic conditions, the physical activity guidelines in Box 9.1 are recommended.

MODE AND DOSAGE

The American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association released a combined position stand in 2007. The recommendation on physical activity for healthy adults under 65 years of age is shown in Box 9.2.

ACCUMULATION OF EXERCISE IS THE KEY

One of the most common excuses people provide for their low level of physical activity is that they simply do not have the time. As can be seen in Boxes 9.1 and 9.2, the total commitment required is only 150 minutes of aerobic exercise per week and 90 minutes of strength training. This is less than 4% of a person’s total waking minutes per week. The key is to be flexible in how this is scheduled. Exercise can be undertaken at any time of day or night, and organised into any preferred blocks of effort, with little decrement in health benefit. So whether the patient completes a single bout of 30 minutes of aerobic exercise in a given day or three blocks of 10 minutes, the effect is essentially the same.

GETTING STARTED

WHAT IS AN EXERCISE PHYSIOLOGIST?

Many medical insurers and government-funded programs around the world include exercise physiologists and may require referral from the GP to the exercise physiologist for the patient to receive a medical insurance rebate, depending on the particular nationalised insurance system. Most private health insurers now cover exercise physiologist services.

COMPONENTS OF AN EXERCISE SESSION

Warm-up

Warm-up facilitates the transition from rest to exercise; it may reduce susceptibility to musculoskeletal injury by improving joint range of motion, and reduce the risk of adverse cardiovascular events.4 Regardless of training mode, exercise sessions should start with 5–10 minutes of low-intensity exercise incorporating stretching exercises and/or progressive lower-intensity aerobic activity. For example, participants who use 20 kg in a chest press exercise for 12 repetitions might have a warm-up set using 5–10 kg for 15 repetitions before initiating this particular exercise. Similarly, participants who use brisk walking or jogging might conduct a warm-up phase using a slow walk before initiating the training program. Implementing a gradual transition from rest to intense exercise is critical in reducing the risk of an adverse event, such as muscle strain or even a cardiovascular event. The body is much more comfortable with gradual changes in exercise intensity.

Specific phase

Cardiorespiratory training includes 20–60 minutes of continuous or intermittent (minimum of 10-minute bouts accumulated during the day) of aerobic activity training at 60–90% maximum heart rate (MHR) or 50–85% MHR reserve.7 Anabolic resistance exercises include performing 1–4 sets per muscle group training at 50–80% of 1 RM (repetition maximum) or 6–12 RM.7 Flexibility or range-of-motion training includes performing 2–4 sets per muscle group at 30–60 seconds stretching time.7

Exercise order

The ordering of anabolic exercises should generally follow these rules:

Cool-down

This phase provides a gradual recovery from the specific activity performed and includes exercises using lower intensities. For example, participants can use slow walking when completing higher-intensity aerobic activity or lower-intensity stretching when completing a resistance training session. The cool-down allows appropriate circulatory adjustment of heart rate and blood pressure to near-resting values, facilitates dissipation of heat, reduces potential post-exercise hypotension and promotes removal of lactic acid.4

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF EXERCISE

EXERCISE PROGRAM VARIABLES

Adaptation

Second, the adaptation is very specific to the stimuli—resistance training tends to produce an increase in muscle size, whereas swimming produces an increase in the heart’s ability to pump blood. The concept of specificity will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Exercise intensity

The intensity of an exercise session refers to how hard someone must push themselves to get benefits from the activity. Intensity and duration of exercise determine the total caloric expenditure of a training session. Similar improvements in the cardiovascular training component may be derived from higher-intensity and short-duration activity or lower-intensity and longer-duration programs.4

Monitoring exercise intensity

Training heart rate

Heart rate (HR) is used extensively as a guide to monitor exercise intensity due to its relationship between heart function and consumption of oxygen by the working body. The most simple and often-used HR assessment is the percentage of maximal HR (maxHR), which can be estimated as 220 – age. The proposed maxHR intensity range for older people during cardiovascular activities is 60–90% of maxHR.4 For example, if an individual is 40 years of age, their maxHR is 180. Their target training heart rate for 60–90% of the maxHR is 108–162 beats per minute.4

Rating of perceived exertion

Rating of perceived exertion (RPE) is a valuable instrument in controlling exercise intensity in individuals who have difficulty with HR palpation and especially in cases where medication can alter the HR response to exercise (e.g. beta-blockers).4 The best known and established RPE scale is the Borg scale. This scale was developed to allow the participant to subjectively rate their feelings during exercise, taking into account fitness level, fatigue and environmental factors.4 More recently, Robertson and colleagues (2003)8 developed the OMNI scale, which uses verbal and pictorial descriptors along a numerical scale of 0–10 to rate an individual’s perceived exertion. This scale has been successfully validated with children and young adults from both sexes during cardiovascular9 and resistance exercise,8 and may also be an option for exercise sessions with older people and patients. RPE can be taken at different points during an exercise session—following each set of an exercise, for example. It can also be taken after the end of the session, which provides a global rating of the exercise session intensity. This measure of session RPE provides essentially the same information as taking multiple measures throughout the session. A sample RPE scale suitable for older people exercising is contained in Figure 9.1.

The talk test

As a method of making exercise prescription more simple, an informal guideline, widely referred to as the talk test, has arisen within the exercise community. This guideline suggests that if the exercise intensity is such that the patient can just respond to conversation, then it may be just about right (that is, within accepted ranges of exercise training intensity). The ability to converse during exercise (that is, to pass the talk test) has been shown to produce exercise intensities consistently within the parameters suggested in clinical guidelines for exercise training in a variety of populations.10 The talk test appears to be a practical way for people to monitor their intensity during exercise, and an advantage of this method is that it does not require any equipment and no training is needed to understand your ability to speak based on how hard you are working. Because research has shown this method to be very consistent, people can use it in their everyday lives, in gyms or when working out at home, to meet their health and fitness goals while reducing the risk of injuries or other complications that can happen with over-exertion.

FREQUENCY

An optimal training frequency for cardiorespiratory fitness in healthy adults has been proposed as three to five times per week, depending on the intensity of the exercise (see Boxes 9.1 and 9.2). However, de-conditioned individuals are likely to improve their condition with lower training frequencies.4

VOLUME

With regard to cardiorespiratory training, the combined duration and intensity of an exercise bout result in the expenditure of energy and calories, giving health benefits from the activity. The duration of cardiovascular activities recommended by the ACSM4 for healthy older adults is 20–60 minutes of continuous or intermittent (minimum of 10-minute bouts accumulated during the day) of aerobic activity training.

VARIATION IN TRAINING

All program parameters can be modified to achieve variation in the training. Intensity and volume are obvious choices and it is well accepted that within a week there should be heavy and light days, and the volume should undulate over longer periods of 4–12 weeks or more. However, subtle changes to exercise may include:

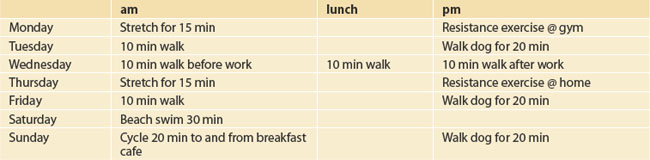

PLANNING AN EXERCISE SCHEDULE

The exercise schedule in Table 9.2 provides sufficient exercise to meet the recommended guidelines for someone under 65 years of age. The intensity should be specific to the individual but within the range previously prescribed.

BARRIERS TO EXERCISE

No one said it was easy to start an exercise program and then stick to it. There are many barriers to exercise that must be overcome. The greatest by far is lack of motivation to change one’s behaviour. The GP can be a powerful influence in taking the patient through the stages of change necessary to make exercise a lifelong habit. Convincing the patient of the importance of exercise for their health and even instilling some fear of the consequences of a sedentary lifestyle can be all it takes to start the process. Other personal, financial, environmental and societal barriers can make it difficult to exercise. However, these can all be overcome if the motivation of the patient and the support of their family and friends is sufficient. Regardless of a patient’s illness or injury, there is still the potential to perform some form of physical activity. For example, research in patients with various cancers indicates that exercise can be tolerated, is effective for improving physical and mental health and may even be enjoyable. Lack of financial means is often cited as limiting exercise opportunities but effective exercise programs do not necessarily require expensive equipment and specialist trainers. A quality exercise program meeting the minimum recommended requirements can be achieved in the home with little or no equipment if the patient is given specialist advice to enhance their motivation to exercise. It has been demonstrated that the environment in which the patient lives can affect their opportunities for exercise. For example, a neighbourhood that appears to be unsafe, and has graffiti and broken and dangerous pathways is clearly not conducive to pursuing a walking program. Societal influences can also reduce a patient’s willingness to maintain an active lifestyle. Teenage girls are less likely to exercise, because of peer pressure. Certain religious and cultural groups devalue exercise or actively discourage it. Many children believe that their elderly parents should rest, not exercise, especially when ill. Exercise research indicates that this strategy is counterproductive.

All these barriers to physical activity can be overcome with education and support.

SAFETY AND AVOIDING INJURY

Exercise can be performed in two broad categories of environment:

OVER-EXERCISING

The ACSM/AHA guidelines presented earlier5 are recommended exercise to maintain health. The volume of exercise can be increased considerably before over-training becomes an issue, but some simple strategies to avoid the syndrome include:

EXERCISE AND DISEASE

DON’T SUFFER THE SIDE EFFECTS

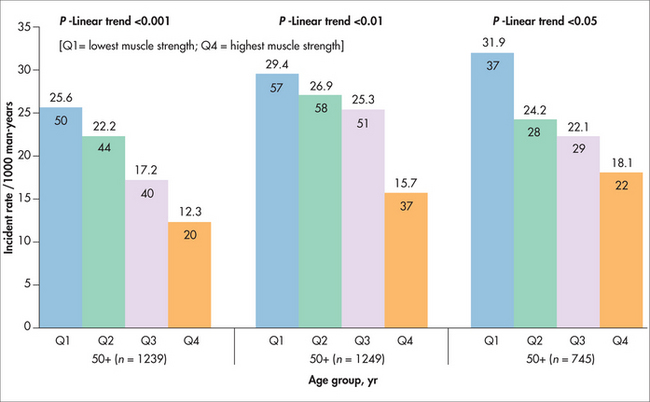

Treatment side effects are of concern to patient and doctor, and decisions have to be made regarding the relative risks and benefits. In some instances, exercise prescription as adjuvant therapy can alleviate some side effects and improve tolerance of pharmaceutical, radiation and other treatments. For example, testosterone suppression for prostate cancer results in muscle and bone loss and fat gain.11 Fracture risk is increased and recent reports indicate a high incidence of cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome.12 It is now well established that exercise can alleviate all these side effects (Figure 9.2).13 Muscular strength is strongly and inversely associated with incidence of metabolic syndrome and the effect is independent of age and body size. Potential benefits of resistance exercise training to increase muscular strength should be considered in primary prevention of metabolic syndrome.14

CANCER

Much of the research to date on exercise and cancer has focused on cancer prevention, and there is strong benefit particularly for colorectal and breast cancers. Recently, research has begun to examine the effectiveness of exercise programs for patients undertaking therapy. All the evidence collected so far suggests that exercise plays a beneficial role for most patients during cancer treatment. The evidence also shows that there is very little risk of harm when precautions are taken and professional exercise advice is followed closely.16

Regular and vigorous physical exercise has been scientifically established as providing strong preventative effect against cancer, with the potential to reduce incidence by 40%. The effect is strongest for breast17 and colorectal cancer,18 but evidence is accumulating for the protective influence on prostate cancer, although predominantly for more advanced disease and in older men.19

Following cancer diagnosis, exercise prescription can have very positive benefits in improving surgical outcomes, reducing symptom experience, managing side effects of radiation and chemotherapy, improving psychological health, maintaining physical function, reducing fat gain and reducing muscle and bone loss (see Table 9.3). There is now irrefutable evidence from large prospective studies that regular exercise post diagnosis actually increases survivorship by 50–60%, with the strongest evidence currently for breast20 and colorectal cancers,21 over follow-up periods varying from 5 to 18 years (see Ch 24, Cancer).

TABLE 9.3 Summary of exercise-induced changes in cancer patients reported in 26 research papers reviewed by Galvão and Newton 20057

| Increased | Decreased |

|---|---|

| Muscle mass | Nausea |

| Muscle strength and power | Fatigue |

| Cardiorespiratory fitness | Symptom experience |

| Maximum walk distance | Lymphocytes and monocytes |

| Immune system capacity | Duration of hospitalisation |

| Physical functional ability | Heart rate |

| Flexibility | Resting systolic blood pressure |

| Quality of life | Psychological and emotional stress |

| Haemoglobin | Depression and anxiety |

| Body fat |

OSTEOPOROSIS

It has been suggested that the most effective way to avoid osteoporosis is to build as large a ‘bone bank’ as possible during life so as to be able to make ‘withdrawals’ as we age without depleting to an osteoporotic level.22 Physical activity is the most effective lifestyle factor to stimulate bone accretion but the activity needs to be ground-based and with higher loads and impacts. For example, bone mineral density in weightlifters is higher than for active controls and this continues into later life.23 The effect is persistent, with one study showing that competitive sport early in life is associated with higher bone mineral density in 75-year-old men.24 Swimming, which lacks impacts and the effects of gravity, does not appear to have a protective effect, and swimmers may actually have a lower bone mineral density than people participating in land-based physical activity.25

Physical activity in later life can improve or at least slow bone loss with ageing, and the most effective activity appears to be anabolic exercise. Walking and similar exercises appear to be too low-intensity, with several studies reporting superior results from high-intensity resistance training,26 and it is significantly more effective than calcium and vitamin D supplementation alone.27

SARCOPENIA

Affecting 60% of people over 80 years old, sarcopenia is a major cause of disability and loss of independence for the elderly. Nutrition (under-nutrition and lack of vitamin D) and decreased hormone levels (growth hormone, testosterone) precipitate some of the muscle loss and the ageing process per se; however, it is clear that reduced physical activity, particularly anabolic exercise, is a major factor. The condition is reversible even in the very old, with appropriate anabolic exercise resulting in large increases in lean muscle mass, fibre cross-sectional area and strength.28 It is well known in athlete and healthy populations that there are optimal combinations of anabolic exercise and nutrition. Specifically, glucose and amino acid intake can be manipulated before, during and after the exercise session to produce much stronger anabolic effects. Supplements such as creatine monohydrate are also effective when combined with anabolic exercise, and more research is being done on their application to patient populations.

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

It has now come to light that the genetic and lifestyle risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease are very similar to those for cardiovascular disease. This is encouraging in one respect in that exercise is beneficial; however, it is problematic in that the various populations of the world are becoming less active, or at least a high percentage are already sedentary, and obesity is increasing markedly. As a result of these lifestyle choices and an ageing demographic, the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease is predicted to increase greatly in the future. Exercise has several roles to play here. First, lifelong physical activity can delay the onset of Alzheimer’s even in those with high genetic predisposition. For example, in one population based-study (n= 1740) with 6.2 years follow-up, the reported incidence rate of dementia was 13.0 per 1000 person-years (exercise three or more times per week) compared to 19.7 per 1000 person-years (exercise fewer than three times per week).29 In the early stages, regular exercise slows the progression of the disease, helping to maintain both physical and cognitive capacity. Interestingly, even a single bout of exercise results in an acute improvement in memory and cognitive function in patients with existing disease.

OBESITY

The evidence is clear that the only effective way to lose body fat when overweight or obese is a combination of habitual physical activity and reduction in energy intake. It appears that increased physical activity alone is not as effective as reduced caloric intake, but it is far easier to stick to a lifestyle in which a negative energy balance is achieved 50% through increased exercise and 50% through diet modification. But the application of exercise for weight management has other important benefits. Any fat-loss diet is also a muscle and bone loss diet as these tissues are also affected. Exercise, and in particular anabolic exercise, is critical for preventing these catabolic effects. Second, exercise increases muscle mass, which concomitantly increases resting metabolic rate, enhancing fat reduction. Finally, in terms of patient health, ‘fitness rather than fatness’ should be the focus, as research indicates that a person can be overweight but if they are physically fit then their risk of death is no greater than a person of normal weight.30 The same cannot be said of someone who is of normal weight but sedentary.

ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION

A number of trials have reported reduced risk of anxiety and depression in children who exercise, compared with inactive controls.31 The evidence in adults is less convincing due to a lack of clinical trials, but there are indications of a positive effect.32 However, in older people diagnosed with clinical depression, certain types of exercise have been demonstrated to be more effective than routine GP care.33 This was a single blind control trial which indicated that high-intensity resistance training could produce a 50% reduction in depression rating in 61% of the group. This compared to a similar drop in only 21% of patients in the GP-care group. A 29% reduction was observed in a low-intensity resistance training group, indicating that social interaction was not the only stimulus but the lifting of heavier weights produces some physiological effect benefiting the depressed elderly.

TYPE 2 DIABETES

Exercise improves glucose tolerance and insulin resistance, and is considered very beneficial for preventing and treating type 2 diabetes. In fact, it is estimated that appropriate levels of physical activity could prevent 30–50% of new cases of type 2 diabetes.34 However, benefits for preventing and treating diabetes occur only with regular sustained physical activity patterns. Aerobic exercise is often hindered in older, obese, comorbid patients, and anabolic exercise has been demonstrated in several studies to be safe and more effective.35

OSTEOARTHRITIS

Osteoarthritis can be severely debilitating and limit participation in physical activity. However, reduced movement will exacerbate the disease. Strong research has demonstrated that exercise, in particular anabolic, can result in increased function as assessed by stair climbing and descending, chair rising, walking, reduced ratings of pain and reduced stiffness. These studies report exercise to be ‘safe, effective and well tolerated in patients with osteoarthritis’.36 Exercise frees joint movement, increases joint lubrication, and slows or even reverses muscle atrophy, resulting in better joint support and improved function.36

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

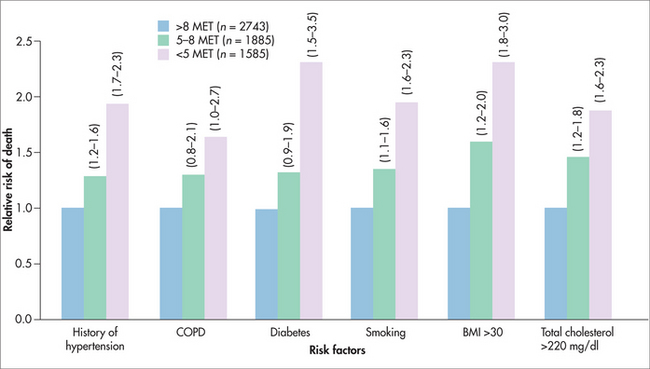

How strong a predictor physical exercise is in reducing mortality is summarised in Figure 9.3.

FIGURE 9.3 Exercise capacity is a more powerful predictor of mortality among men than other established risk factors for cardiovascular disease.14 MET: metabolic equivalent tasks.

Some decades ago, the medical advice for patients post stroke or heart attack was rest; however, research revealed that the outcomes were quite poor with this strategy. It is now recognised that exercise is a critical therapy for recovery from such events, especially when it is applied at the early stage recovery in the long-term management plan. Both aerobic and anabolic exercise modes are used and have been demonstrated to significantly reduce mortality and morbidity.38

SUMMARY

Human physiology expects and requires regular exercise for normal health and maintenance of physical and psychological function. Despite this overwhelming evidence, two-thirds of the population are sedentary or have low physical activity levels despite the best efforts of health promotion. This behaviour is driving a catastrophic rise in chronic disease incidence across the world, such that by 2020 it is predicted that 80% of the health burden will be due to these largely preventable illnesses. For all patients with chronic disease, illness or injury, exercise plays a role as a primary or adjuvant therapy. Exercise physiologists are the most qualified and appropriate allied healthcare professionals for the assessment, prescription and monitoring of exercise programs for chronic disease management. Exercise should form a component of all patient management plans as a critical aspect of integrative medicine.

Australian Association for Exercise and Sports Science. http://www.aaess.com.au.

Heart Foundation. www.heartfoundation.com.au. Companion readings from this website:

National Heart Foundation of Australia, Physical Activity Policy

Promoting physical activity – ten recommendations from the Heart Foundation

Physical activity and children: a statement of importance and call to action

VicFit in Victoria / Kinect Australia. www.vicfit.com.au. Companion readings from this website:

1 Booth FW, Gordon SE, Carlson CJ, et al. Waging war on modern chronic diseases: primary prevention through exercise biology. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88(2):774-787.

2 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian snapshots. Physical activity in Australia: a snapshot. Online. Available: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4835.0.55.001, 2004/05.

3 Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. 2007 Australian National Children’s Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey. Online. Available: http://www.health.gov.au/nutritionmonitoring.

4 American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000.

5 Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2007;39(8):1435-1445.

6 Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2007;39(8):1423-1434.

7 Galvão DA, Newton RU. Review of exercise intervention studies in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(4):899-909.

8 Robertson RJ, Goss FL, Rutkowski J, et al. Concurrent validation of the OMNI perceived exertion scale for resistance exercise. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2003;35(2):333-341.

9 Robertson RJ, Goss FL, Dube J, et al. Validation of the adult OMNI scale of perceived exertion for cycle ergometer exercise. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2004;36(1):102-108.

10 Persinger R, Foster C, Gibson M, et al. Consistency of the talk test for exercise prescription. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(9):1632-1636.

11 Galvão DA, Spry NA, Taafe DR, et al. Changes in muscle, fat, and bone mass after 36 weeks of maximal androgen blockade for prostate cancer. Brit J Urol Int. 2008;102:44-47.

12 Keating NL, O’Malley AJ, Smith MR, et al. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease during androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(27):4448-4456.

13 Galvão DA, Nosaka K, Taaffe DR, et al. Resistance training and reduction of treatment side effects in prostate cancer patients. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2006;38(12):2045-2052.

14 Myers J, Prakash M, Froelicher V, et al. Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(11):793-801.

15 Jurca R, Lamonte MJ, Barlow CE, et al. Association of muscular strength with incidence of metabolic syndrome in men. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2005;37(11):1849-1855.

16 Newton RU, Galvao DA. Exercise in prevention and management of cancer. Curr Treat Opt Onc. 2008;9(2/3):135-146.

17 Friedenreich CM, Cust AE. Physical activity and breast cancer risk: impact of timing, type and dose of activity and population sub-group effects. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42:636-647.

18 Samad AK, Taylor RS, Marshall T, et al. A meta-analysis of the association of physical activity with reduced risk of colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7(3):204-213.

19 Nilsen TIL, Romundstad PR, Vatten LJ, et al. Recreational physical activity and risk of prostate cancer: A prospective population-based study in Norway (the HUNT study). Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2943-2947.

20 Holmes MD, Chen WY, Feskanich D, et al. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2005;293(20):2479-2486.

21 Demark-Wahnefried W. Cancer survival: time to get moving? Data accumulate suggesting a link between physical activity and cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(22):3517-3518.

22 Bailey DA, Faulkner RA, McKay HA, et al. Growth, physical activity, and bone mineral acquisition. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1996;24:233-266.

23 Karlsson MK, Hasserius R, Obrant KJ, et al. Bone mineral density in athletes during and after career: a comparison between loaded and unloaded skeletal regions. Calcif Tissue Int. 1996;59(4):245-248.

24 Nilsson M, Ohlsson C, Eriksson AL, et al. Competitive physical activity early in life is associated with bone mineral density in elderly Swedish men. Osteoporosis Int. 2008;19(11):1557-1566.

25 Bellew JW, Gehrig L. A comparison of bone mineral density in adolescent female swimmers, soccer players, and weight lifters. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2006;18(1):19-22.

26 Humphries B, Newton RU, Bronks R, et al. Effect of exercise intensity on bone density, strength, and calcium turnover in older women. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2000;32(6):1043-1050.

27 Kemmler W, Engelke K, Weineck J, et al. The Erlangen Fitness Osteoporosis Prevention Study: a controlled exercise trial in early postmenopausal women with low bone density—first-year results. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2003;84(5):673-682.

28 Fiatarone MA, Marks EC, Ryan ND, et al. High-intensity strength training in nonagenarians. Effects on skeletal muscle. JAMA. 1990;263(22):3029-3034.

29 Larson EB, Wang L, Bowen JD, et al. Exercise is associated with reduced risk for incident dementia among persons 65 years of age and older. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(2):73-81.

30 Sui X, LaMonte MJ, Laditka JN, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and adiposity as mortality predictors in older adults. JAMA. 2007;298(21):2507-2516.

31 Larun L, Nordheim LV, Ekeland E, et al. Exercise in prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression among children and young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD004691.

32 Mead GE, Morley W, Campbell P, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD004366.

33 Singh NA, Stavrinos TM, Scarbek Y, et al. A randomized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(6):768-776.

34 Manson JE, Spelsberg A. Primary prevention of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(3):172-184.

35 Willey KA, Singh MA. Battling insulin resistance in elderly obese people with type 2 diabetes: bring on the heavy weights. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(5):1580-1588.

36 Bennell KL, Hunt MA, Wrigley TV, et al. Muscle and exercise in the prevention and management of knee osteoarthritis: an internal medicine specialist’s guide. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93(1):161-177.

37 Cook NR, Cohen J, Hebert PR, et al. Implications of small reductions in diastolic blood pressure for primary prevention. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(7):701-709.

38 Taylor RS, Brown A, Ebrahim S, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for patients with coronary heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Med. 2004;116(10):682-692.