Chapter 35 Evaluation of Male Infertility

INTRODUCTION

A defect in male fertility can be found in up to 50% of couples with infertility. The male is the only cause of infertility in 30% of cases, and a combination of male and female factors can be found in another 20%.1 In the past, a combination of a lack of understanding of the pathophysiology of male infertility and a paucity of successful treatment modalities often led to neglect of the male in the evaluation process. In some cases women have undergone invasive testing and treatment before evaluation of their mate, only to find on subsequent semen analysis that the male partner was the source of the couple’s infertility. In other cases, the discovery of a markedly abnormal result on semen analysis has led to the immediate application of in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF/ICSI) before a full evaluation of the male partner has been undertaken. In either case, the affected couple does not receive the optimal benefit of the extensive diagnostic and treatment modalities that have been developed for male infertility over the past 20 years.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

When male infertility is discovered, it is imperative for the man to be evaluated by a male infertility specialist before attempting pregnancy for several reasons. In some conditions, treatment modalities can improve the prospects of a couple achieving pregnancy. In others, careful evaluation will determine the presence of associated medical problems.2 For some couples with male infertility, genetic testing is essential to give prognostic information as to potential success and genetic risk assessment for the potential progeny to infertile couples considering treatment.3 In those men whose evaluation does not reveal a potentially treatable condition, contact with a male infertility specialist during the evaluation process completes the team that will implement comprehensive treatment plans that might include sperm retrieval with assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs).

Treatable Causes of Male Infertility

Many men with male infertility will be found to have conditions amenable to surgical or medical treatment. Varicocele surgery has become more reliable and less invasive due to introduction of improved surgical techniques, such as the microsurgical subinguinal approach.4,5 Surgical repair of epididymal obstructions has enjoyed higher success rates with introduction of invagination techniques.6 In men with clear-cut endocrinopathies, medical treatments are highly successful in improving fertility.7

Associated Medical Problems

Male infertility increases the risk of other potentially dangerous medical problems, such as testicular cancer, spinal cord and brain tumors, genitourinary malformations, and chromosome aberrations.3 Men with severe oligospermia should be fully evaluated for these conditions before being directed toward attempts at pregnancy with IVF/ICSI. Failure to evaluate the male for these problems may delay the diagnosis of these potentially dangerous conditions.

Genetic Testing

In recent years, our understanding of the genetics of male infertility has markedly improved. For example, it is now standard to perform Y-chromosome microdeletion testing in men with azoospermia or severe oligospermia, because aberrations in spermatogenesis have been linked to Y-chromosome microdeletions.2 Using this approach, an underlying genetic problem can be determined in many of these men whose abnormalities would have been designated as idiopathic in the past.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The list of possible causes of male infertility is extensive (Table 35-1). Causative conditions and factors can almost always be identified by a detailed history, physical examination, and semen analysis. Some of the most common causes are explored below in more detail.

Varicocele

A varicocele is the single most commonly identified surgically treatable condition found in men with abnormal results on semen analysis. It has been reported that in asymptomatic men with a palpable varicocele, an abnormality on semen analysis will be found in 70%. A varicocele is present in approximately 35% to 40% of men with primary infertility and 80% of men with secondary infertility.8,9 However, not all men with a varicocele will be infertile, and this entity will be found in approximately 15% of all men. The majority of varicoceles will be found on the left side, but they can be either unilateral or bilateral.

The mechanism by which a varicocele causes impaired testicular function is poorly understood. It is well accepted that the presence of a varicocele is associated with progressive decline of testicular volume, impaired sperm quality, and loss of Leydig cell function.10 It has been shown that larger varicoceles are associated with greater impairment of testicular dysfunction compared to smaller varicoceles.11,12 Theories proposed to explain these observations include increased testicular temperature from loss of the countercurrent mechanism present in the normal spermatic cord, hypoxia, and reflux of renal or adrenal hormonal metabolites.13–15

Treatment

Several techniques exist to repair a varicocele, including surgical and radiographic intervention. These techniques are described in more detail in the subsequent chapter. Repair of a varicocele has been shown to improve spermatogenesis, increase Leydig cell function, and prevent further decline in testicular size.16–18 Many studies have evaluated the effectiveness of varicocele repair on improving pregnancy rates. However, most studies have been retrospective and poorly controlled.

To date, only two randomized, prospective, case-controlled studies of varicocele have been performed. The first study randomized patients to surgical repair, radiographic embolization, or observation.19 Unfortunately, 48% of patients in this study had a grade 1 varicocele, for which repair is of questionable value. Although there was significant improvement in semen parameters in the patients receiving intervention, no difference was seen in pregnancy rates.

The second study was a crossover design.20 A total of 45 couples underwent either immediate or delayed repair of a varicocele after 1 year of observation. Pregnancy rates were 60% during the first year for those undergoing immediate repair compared to 10% for those in the observation group. For the latter group, pregnancy rates increased to 44% during the subsequent year after repair.

Genetic Causes of Male Infertility

A detailed discussion of the genetics of reproduction is given in Chapter 5.

Klinefelter’s Syndrome

Klinefelter’s syndrome is a chromosomal aberration resulting in a genotype of 47,XXY in 90% of cases or the mosaic form of 46,XY/47,XXY in the remaining 10% of patients.21 Classically, men present as tall, eunuchoid appearance with azoospermia, gynecomastia, and small firm testes. However, a spectrum of presentations exists, especially in the mosaic form. Diagnosis is confirmed with a karyotype. Sperm extraction with ICSI has been reported in this patient population; however, couples should undergo preoperative counseling regarding risks of genetic transmission.

Cystic Fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis is the most common autosomal recessive disorder in whites.22 It is associated with congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens in addition to pulmonary disease and exocrine pancreas dysfunction. Patients with this disease have mutations in the CFTR gene. This gene makes a protein responsible for chloride channel formation, and these mutations result in nonfunctioning channels. The mechanism by which these mutations result in degeneration of the developing vas deferens remains to be determined.

An atypical form of cystic fibrosis should be suspected in any apparently healthy man with azoospermia and bilateral absence of the vas deferens on examination.22 More than half of these men will be found to have mutations in the CFTR gene. Because of the high carrier rate for cystic fibrosis in the population, all men with congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens and their spouses should be screened for CFTR gene mutations. It is imperative that couples at risk for creating embryos with homozygous gene mutations for cystic fibrosis undergo genetic testing and counseling before proceeding with sperm harvesting and ICSI.

Y-Chromosome Microdeletions

Successful pregnancies have been reported using ICSI for men with AZFc deletions; however, no patient with AZFa or AZFb deletions has been reported to have sperm on testicular biopsy.23–25 Although no somatic changes are evident in the offspring of patients with AZFc deletions, couples should be counseled that the genetic mutation will be transmitted to male progeny, who will face similar fertility issues in the future.

Ejaculatory Dysfunction

Medications

Several classes of frequently used medications can cause ejaculatory dysfunction. The antiadrenergic properties of antihypertensives (e.g., methyldopa, doxazosin) can cause incomplete closure of the bladder neck, leading to retrograde ejaculation or in extreme cases failure of emission. Commonly used antidepressants (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]) and antipsychotics (e.g., thioridazine, clozapine) are also well-known causes of either delayed ejaculation or anejaculation.26,27

Diabetes Mellitus

Although erectile dysfunction is a more common finding in patients with diabetes mellitus, ejaculatory dysfunction may also be present due to the autonomic neuropathic effects on the sympathetic chain controlling the bladder neck. Difficulties with ejaculation or emission are present in up to 32% of diabetic patients.28

Medications and Male Infertility

Anabolic Steroids

Normal levels of intratesticular testosterone are essential for normal spermatogenesis, and these levels are significantly higher than peripheral testosterone levels.30 Use of anabolic steroids causes suppression of normal testicular feedback from the testes to the hypothalamus and pituitary, thus leading to decreased intratesticular testosterone levels and impaired spermatogenesis.31 Cessation of the exogenous androgens usually allows for resumption of normal spermatogenesis. However, there are case reports of continued disorders of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis after discontinuation of anabolic steroid use.

Chemotherapy

Many chemotherapy agents are know to cause damage to germinal epithelium. As a general rule, the severity of gonadal toxicity is dose-dependent and is related to the class of chemotherapeutic agent used. Although some men will have recovery of spermatogenesis up to 5 years after treatment, a subset of men receiving chemotherapy will have permanent sterility.32 Before initiating chemotherapy there is currently no way to predict which men will have return of fertility. Consequently, sperm banking should be offered to all men before treatment.

EVALUATION OF THE MALE

Male Partner History

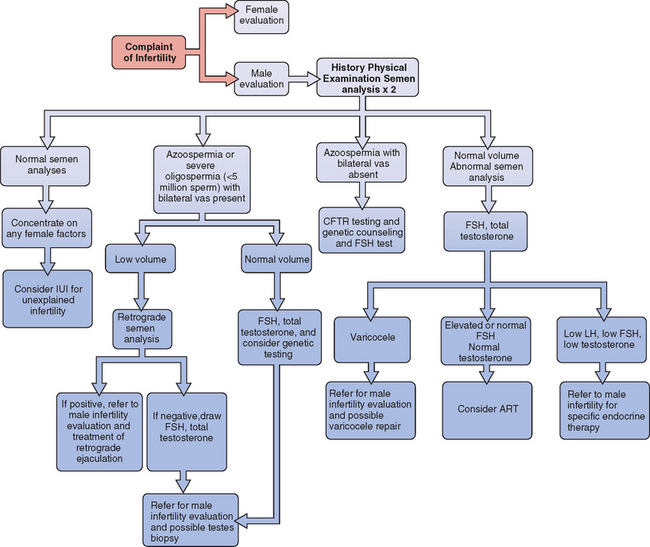

All evaluations of the infertile couple require a careful history from the male in addition to a semen analysis. In most infertility practices, physical examination of the male is performed only if the semen analysis is abnormal or if there is a history of some abnormality. An algorithm for the evaluation of male infertility is presented in Figure 35-1.

General History

The clinician should also inquire about any previous evaluation and treatment for male or female factor infertility and should discuss any systemic illness within the past 6 months, particularly if it was a febrile illness.33 The review of systems should specifically include recent weight gain or loss, fevers, colds, sinus infections, anosmia, peripheral field visual problems, breast pain or secretions, and scrotal pain.

Evaluation should also include any potential exposure to environmental toxins, either through occupation or hobbies. This includes such factors as excessive heat, radiation, heavy metals, and glycol ethers or other organic solvents because these may each have an effect on spermatogenesis.34

Past Medical History

The evaluation should then proceed to a history of any condition that would potentially affect the genitals or endocrine system. Infertility in the male can be the presenting symptom of other serious conditions, and careful evaluation is vital. Pertinent findings would include a history of cryptorchidism, significant genital trauma, previous diagnosis of varicocele, hypothyroidism, or known pituitary malfunction. It will also include a review of any additional medical conditions for which the patient is being followed, including any condition that would require radiotherapy or chemotherapy. Diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sleep apnea, renal insufficiency, and hepatic insufficiency are possible contributors to male subfertility.35 Prior sexually transmitted infections can lead to obstruction of the genital ducts.

Surgical History

Past surgical events of note include any genitourinary surgeries such as orchiopexy, YV plasty to the bladder neck, inguinal hernia repair, correction of epispadias or hypospadias, prostate surgery, bladder reconstructions, bladder surgeries, or testicular surgeries. Additionally, one should inquire about previous treatment for testicular or other urologic malignancies, either with surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation, and obviously previous vasectomy. The surgical history should specifically ask about procedures that may impair ejaculation due to injury to the retroperitoneal sympathetic nervous system. The most common procedure would be retroperitoneal lymph node dissection performed for testicular carcinoma.36

Sexual and Fertility History

The history should include the overall pattern of sexual activity, specifically in relation to ovulation.37–39 One should inquire about any previously fathered children as well as any evaluation or treatment of the female partner that may have preceded the patient’s visit, such as the use of ovulation predictor kits or medications. The couple must also be asked about the use of lubricants during sexual intercourse. Many commercially available lubricants are known to impair sperm motility.40

The timing of sexual intercourse in relation to ovulation should be noted because simply adjusting the timing of intercourse can result in an increased chance for pregnancy. Recent data suggests that daily intercourse beginning 5 days before ovulation may be the best intercourse pattern to optimize the chance of pregnancy.37

The patient should be carefully questioned about ejaculatory dysfunction, including pain with ejaculation and hematospermia. Common types of ejaculatory dysfunction include anejaculation (complete lack of ejaculation despite a normal sensation of orgasm), anorgasmia (inability to achieve climax), and retrograde ejaculation, which can appear identical to the patient to anejaculation. Anejaculation and retrograde ejaculation can be the result of a variety of surgical procedures, progressive neurologic disease, or medications.38 Anorgasmia may be psychogenic or due to medications, most notably SSRIs, commonly given for depression.39

Medication History

A careful medication history is an important part of the initial evaluation of the male presenting for evaluation of male factor infertility. The use of calcium channel blockers has been implicated in decreased sperm fertilization potential.41 Spironolactone can contribute to a decreased fertilization capacity and a decline in spermatogenesis.42 Anabolic steroid use can also result in profound decline in sperm counts.31 The patient must also be asked about the ingestion of nutriceuticals and other over-the counter medications.

Social History

Smoking, alcohol consumption, and marijuana use have all been implicated as gonadotoxins.35 A careful history of the use of these agents and other illicit drugs must be part of the male infertility evaluation.

Family History

The family history should include a discussion of testicular or other urologic malignancies specifically, as well as a history of any cancers. The risk of certain cancers, such as prostate cancer, may be greatly elevated in men with a family history. A history of maternal medication use while pregnant with the patient should be noted because exposure to some medications in utero has been implicated in fertility reduction.43 The patient should be queried regarding siblings or extended family members who may have had fertility problems.

Physical Examination of the Male

Genitalia

Palpation of the genitalia is the most important part of the male infertility physical examination. It is important to perform the scrotal examination in a warm room, to prevent scrotal muscle contraction, thus impairing the examination. The size and location of each testicle should be noted. The patient may have a testicle that is palpable in the inguinal canal or that cannot be palpated at all. Masses within the testicle may indicate the presence of a testicular tumor. Masses adjacent to the testicle may indicate cystic changes within the epididymis that may impair sperm flow. The epididymis should also be examined for the presence of induration, cysts, or masses.

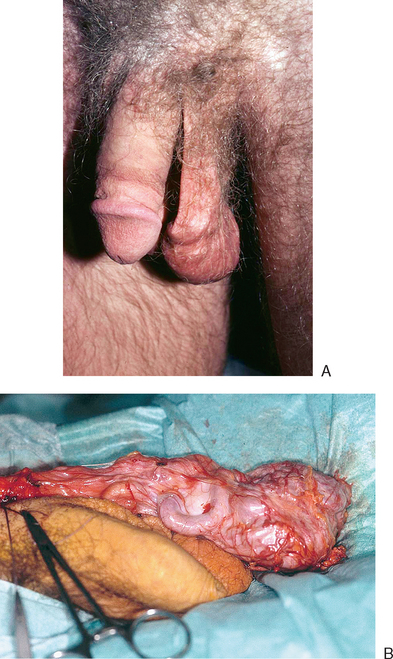

One of the most important parts of the physical examination is determining the presence or absence of a varicocele. The patient should be examined in the standing position, both at rest and with Valsalva. In the standing position, the scrotum should be observed to see if the varicocele is actually visible (Fig. 35-2). These maneuvers are important in the grading of clinical varicoceles (Table 35-2). It is also important to subsequently examine the patient in the recumbent position. When supine, all dilation of testicular veins should disappear. If veins remain dilated, this may indicate the presence of retroperitoneal pathology, such as neoplasms, with the varicocele the result of arteriovenous shunting.

| Grade | Clinical Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Subclinical | Evident on ultrasound only |

| Grade 1 | Palpable only when standing and with Valsalva maneuver |

| Grade 2 | Palpable when standing at rest |

| Grade 3 | Grossly visible when standing |

The characteristics of a varicocele on physical examination have clinical importance. A varicocele that does not disappear in the recumbent position requires retroperitoneal imaging studies. The physician may be more inclined to repair grade 3 varicoceles, due to greater improvement seen with surgery. In adolescents, when sperm counts are not available, one might be inclined to repair a grade 3 varicocele, those with bilateral lesions, or those in which testicular atrophy is present.11,44

LABORATORY TESTING

Semen Analysis

Semen analysis is the cornerstone of laboratory testing of male infertility.45 Still, much controversy exists about the absolute utility of this modality. No one would argue that severe deficiencies in sperm count such as azoospermia will have a profound effect on the ability to initiate a pregnancy. The importance of more subtle derangements is less clear.

Standard Semen Definitions

Collection

There should be a standard abstinence period of 2 to 5 days between the last ejaculation and the time of the semen analysis. This represents only a standard and not necessarily an attempt to optimize all aspects of the semen analysis. For example, it is possible that a longer abstinence period would result in a higher count, but after several days of abstinence, there may be storage of sperm in the seminal vesicles and resultant lowering of sperm motility.46 Also, motility might be optimized by an abstinence period of 12 hours, but count will probably be impaired.

It is important to remember that there is great variability in semen parameters within subjects over time.47 Therefore, patients should have two or three semen analyses separated by 2 to 3 weeks each to ensure that the trend over time is seen. Also, because the sperm production cycle requires 70 to 90 days, the results of an insult to sperm production or a treatment that may improve sperm production will not be seen until that period of time has elapsed. Therefore, performing a semen analysis less than 3 months after an intervention may be misleading.

Normal Semen Parameters

The World Health Organization (WHO) criteria are the most commonly used in large fertility clinics (Table 35-3).45 When perusing a report from a laboratory that reports normal ranges substantially different from those criteria, one has to suspect that the laboratory may not have a great deal of experience in performing semen analysis.

Table 35-3 Normal Ranges for Semen Analysis According to the World Health Organization45

| Semen Characteristics | Normal Values |

|---|---|

| Volume | ≥2 mL |

| pH | 7.2–8.0 |

| Sperm concentration | ≥20 × 106/ml |

| Total sperm count | ≥40 × 106/ejaculate |

| Motility within 1 hour of ejaculation |

Morphology

The largest variation between fertility centers is seen in the choice of morphology standards. The WHO and Kruger (or strict criteria) morphology systems have different methodologies and different normal ranges. Many fertility centers have adopted the Kruger morphology. This system was developed and tested prospectively in a cohort of couples undergoing IVF. Although fertilization rates dropped when Kruger morphology fell below 15%, the rates didn’t drop to extremely low levels until the 0% to 4% range. Many fertility centers use a value of less than 5% as evidence that ICSI is necessary during an IVF cycle.48

Antisperm Antibody Testing

Sperm antibodies contribute to male infertility in 9% to 36% of cases of infertility.49 Because the presence or absence of antibodies cannot be predicted based on history or physical examination, routine screening should be carried out on all semen analysis specimens obtained for the evaluation of infertility.

Endocrine Assessment

Endocrinopathies can lead to male infertility. Individuals with abnormal semen parameters should have determination of total serum testosterone and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels.50 Although free (i.e., bioavailable) testosterone levels may be an important discriminator of men with peripheral hypogonadism, the relationship of these values to intratesticular testosterone is only beginning to be understood.30 Therefore, one cannot necessarily justify the more expensive and involved laboratory test.

The FSH level is extremely useful in differentiating men with obstructive azoospermia from those with nonobstructive azoospermia. Any elevation of FSH out of the normal range in the setting of azoospermia is suggestive of a sperm production problem. However, one must remember that some men with a production problem can also have a normal FSH level. Therefore, FSH is helpful in azoospermic men but not absolutely diagnostic.

Genetic Testing

Congenital Bilateral Absence of the Vas Deferens

Men with classic cystic fibrosis uniformly suffer from infertility due to absence of vas deferens.51 More than half of men with congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens but no obvious symptoms of cystic fibrosis are likely to have a mutation of the CFTR gene. In fact, the chance of finding mutations in this patient population has increased at about the same rate as discovery of previously unrecognized mutations in the general population.

Men with congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens can initiate a pregnancy routinely with sperm retrieval coupled with IVF/ICSI. Before attempting to achieve pregnancy in these patients, it is essential to assess the genetic risk to the potential offspring, because these men are likely to have two abnormal copies of the CFTR gene. With a carrier rate in the white population of a CFTR gene mutation of approximately 4%, genotyping of both the patient and partner is essential to minimize the risk of having a child with cystic fibrosis.52 Whether or not the female partner is found to be a carrier, the patients can be apprised of the risk of having a child with congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens or cystic fibrosis, as well as the implications of carrier status in the children.

Severe Oligospermia

Karyotyping should be performed in men with azoospermia or severe oligospermia (sperm concentrations <5 ′ 106/mL).53 The most common karyotypic abnormality that will be found in these patients is Klinefelter’s syndrome (47,XXY), but other aberrations of sex chromosomes may be seen as well. Although the role of autosomes in controlling sperm production is unclear, Robertsonian translocations may also be seen. In recurrent miscarriage, a balanced translocation may be present in the father, which becomes unbalanced in the embryo.

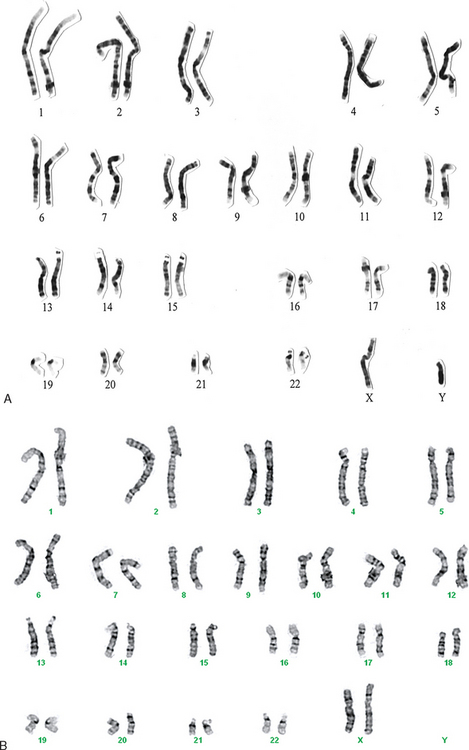

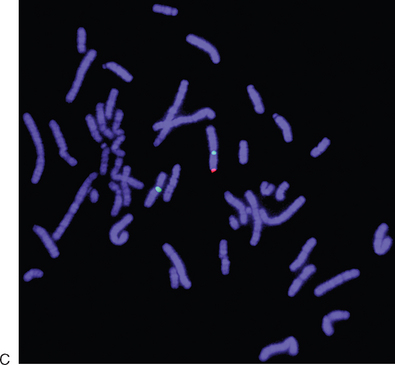

Y-chromosome microdeletion testing should be performed on all men with nonobstructive azoospermia for two reasons: genetic risk counseling and determining prognosis for sperm retrieval. It is highly likely that any male offspring produced with sperm retrieval and ICSI will exhibit the identical Y-chromosome abnormality of the father. Many couples will proceed with the treatment anyway, but they should be given the information to make an informed decision. If a deletion is found and is limited to the AZFc region, it is likely that attempts at sperm retrieval will be successful. However, current evidence suggests that if deletions are found in the AZFa or AZFb region, attempts at sperm retrieval will be futile.54 A normal karyotype and a karyotype from a variation of Y-chromosome microdeletion in an XX male are shown in Figure 35-3.

IMAGING STUDIES

Scrotal Ultrasound

A scrotal ultrasound may be used as an adjunct to physical examination in assessing testicular or other scrotal masses. Scrotal ultrasound may also be used to measure testicular size or confirm testicular or paratesticular masses or cysts suspected by physical examination. The presence or absence of the vas deferens can be confirmed by physical examination alone and should not require ultrasound. In patients with unilateral absence of the vas deferens, consideration should be given to obtaining a renal ultrasound or intravenous pyelogram to evaluate the ipsilateral kidney because there is a strong correlation with renal anomalies in these patients.55

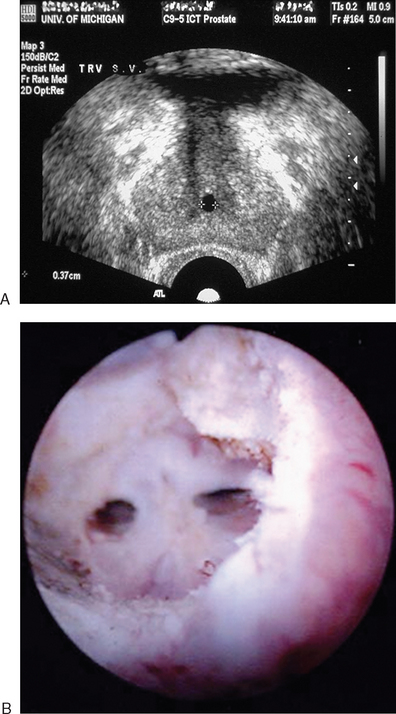

Although the diagnosis of varicocele is made by physical examination, in select patients ultrasound may aid in diagnosis. Various criteria have been used to define varicocele on ultrasound. Some authors have used a 2 to 3 mm diameter of any scrotal vein as diagnostic; others have suggested that the definition include the presence of three or more veins with at least one 3 mm in diameter at rest.56,57 Additionally, reversal of blood flow on Doppler ultrasound during Valsalva maneuver has also been used by clinicians for diagnosis. An ultrasound of a man with a clinical varicocele is shown in Figure 35-4.

Although there are some reports of the utility of ultrasound in the diagnosis of varicocele, the usefulness of this approach remains controversial. Problems with ultrasound diagnosis of varicocele include variability in interpretation and lack of standards in determining what constitutes a varicocele on ultrasound. Furthermore, recent reports have suggested that the subclinical varicocele (a varicocele diagnosed only by ultrasound and not evident on physical examination) is not a true clinical entity. One study found that men with subclinical varicocele did not have improved semen parameters after varicocele surgery, in contrast to those with varicoceles diagnosed by physical examination.21

Vasogram

A vasogram is accomplished by injecting X-ray contrast medium through the vas deferens lumen and monitoring the flow via fluoroscopy or plain films. The purpose is to localize a site of obstruction to sperm flow. This is a test that should be performed only at the time of definitive repair of the lesion. All too commonly, vasogram is performed by nonspecialists at the time of a testis biopsy, opening up the possibility of creating a second site of obstruction due to scarring at the vasogram site. This problem is prevented by performing the vasogram only at the time of definitive reconstruction. A vasogram in a man with ejaculatory duct obstruction is shown in Figure 35-5.

Transrectal Ultrasound

A transrectal ultrasound has an important role in the evaluation of male infertility. In men with low semen volume and azoospermia, complete obstruction of the ejaculatory ducts may be found. The unobstructed ejaculatory duct typically is 4 to 8 mm in diameter and can be difficult to image,58 but in the presence of obstruction, one may find dilation of the seminal vesicles (>15 mm anteroposterior diameter), midline calcifications, or müllerian or Wolffian duct cysts (Fig. 35-6).

Similar findings may be seen in partial ejaculatory duct obstruction, suspected in men with low semen volume and variable aberrations on semen analysis short of frank azoospermia. Transrectal ultrasound may also be helpful in men suspected of having a vas deferens abnormality, but in whom the physical examination is equivocal (an uncommon event—usually the vas deferens are present or absent). In those men, there may be unilateral or bilateral atresia of the seminal vesicles.

TREATMENT OF MALE INFERTILITY

Interventional Procedures

Intrauterine insemination is often used to treat mild male factor infertility (see Chapter 36). Details of specific surgical procedures used to treat male infertility are found in Chapter 53. The following are specialized interventional procedures that can be used in selective cases for diagnosis or therapy.

Testis Biopsy

The role of testis biopsy has been changing with the success of sperm acquisition and ARTs in the treatment of nonobstructive azoospermia.59 However, there still remains a role for diagnostic biopsy in the assessment of azoospermia.

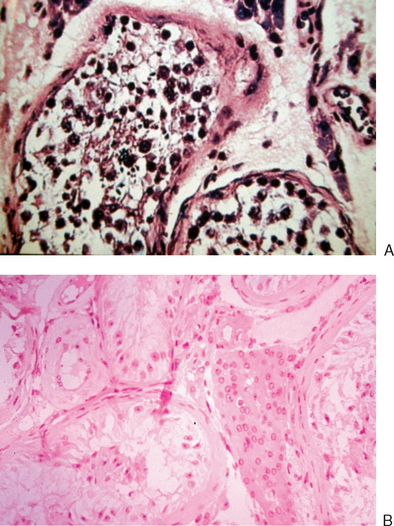

Diagnostic testis biopsy is indicated in men who have azoospermia but conflicting information as to whether it is obstructive or nonobstructive. Men with a clear clinical picture of small-volume testes, elevated serum FSH, and azoospermia do not require a biopsy to determine that they have a sperm production problem. However, in men with conflicting information, it may be helpful. An example might be a man with testis volume of 20 mL, an FSH near the upper limit of normal, and azoospermia. The goal of a biopsy in this man would be to determine if sperm production is normal, indicating that an obstruction may be present that might be remediable by surgical intervention. Figure 35-7 shows the contrast between a normal biopsy and that of a man with Sertoli-cell-only syndrome.

In men with a diagnosis of germ cell deficiency, biopsy is generally used as a therapeutic procedure. The primary purpose of the biopsy is to obtain sperm for IVF/ICSI.

Seminal Vesicle Aspiration

A seminal vesicle aspiration has been suggested to be an adjunctive procedure to ultrasound in the diagnosis of ejaculatory duct obstruction. In his evaluation of normal men, Jarow60 found that the postejaculatory seminal vesicle aspirates were devoid of sperm. It was not until the ejaculatory abstinence time reached 5 days that sperm were stored in the seminal vesicles. His finding of large numbers of sperm in the seminal vesicle fluid after ejaculation in men with ejaculatory duct obstruction led him to conclude that postejaculation examination of seminal vesicle aspirates (>10 sperm per unspun high power field) may be a better discriminator of ejaculatory duct obstruction than simple measurements of seminal vesicle diameters.60

Because men will accumulate sperm normally after long periods of ejaculatory abstinence, this test can also be used to give indirect evidence of unilateral vas deferens obstruction. We have arbitrarily suggested an abstinence time of 3 weeks. An aspirate of the seminal vesicles showing no sperm on one side with an abundance of sperm on the other side suggests obstruction on the former side.61

Ejaculation Induction

In anejaculatory men who fail medical management, one can entertain the possibility of ejaculation induction procedures, including electroejaculation and penile vibratory stimulation.38 The patients who benefit most commonly from this approach are patients with spinal cord injuries, because less than 20% of them will maintain ejaculatory function.

Medical Therapy

Empiric Clomiphene Citrate

To boost testosterone levels in the subfertile male, the synthetic antiestrogen clomiphene citrate can be given orally, usually at a dose of 25 mg daily. Clomiphene increases production of both testosterone and sperm by blocking feedback inhibition at the hypothalamic level, thus resulting in an increase in FSH and LH. Several uncontrolled studies appear to show a benefit of empiric clomiphene for the treatment of male infertility. However, a controlled trial in 23 men showed that although clomiphene citrate therapy resulted in increased levels of LH, FSH, and testosterone, there was no difference between placebo and clomiphene citrate in terms of either semen parameters or pregnancy rates.62

Sympathomimetics

If there is an issue with retrograde or low-volume ejaculation, a trial of sympathomimetics can be useful. The goal of this therapy is to convert the retrograde ejaculation to antegrade or partially antegrade ejaculation. A variety of medications, such as the alpha1-adrenergic agonist methoxamine, have been used with varying degrees of success.38 This approach is more successful with a progressive decline in function, such as seen with neurologic disease, than with the abrupt onset seen as a result of surgery.

L-carnitine

Use of L-carnitine has been proposed as a supplement that can improve sperm motility and count. However, its use remains unproven. Although carnitine may have a role in the maturation of sperm, the trials to evaluate its utility in treating male factor infertility have methodological problems, and more work needs to be done.63

1 Macleod J. Semen quality in 1000 men of known fertility and 800 cases of infertile marriages. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:862-868.

2 Pryor JL, Kent-First M, Muallem A, et al. Microdeletions in the Y chromosome of infertile men. NEJM. 1997;336:534-539.

3 Jarow JP. Life-threatening conditions associated with male infertility. Urol Clin North Am. 1994;21:409-415.

4 Goldstein M, Gilbert BR, Dicker AP, et al. Microsurgical inguinal varicocelectomy with delivery of the testis: An artery and lymphatic sparing technique. J Urol. 1992;148:1808-1811.

5 Marmar JL, Kim Y. Subinguinal microsurgical varicocelectomy: A technical critique and statistical analysis of semen and pregnancy data. J Urol. 1994;152:1127-1132.

6 Berger RE. Triangulation end-to-side vasoepididymostomy. J Urol. 1998;159:1951-1953.

7 European Metrodin HP Study Group. Efficacy and safety of highly purified urinary follicle-stimulating hormone with human chorionic gonadotropin for treating men with isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:256-262.

8 Gorelick JI, Goldstein M. Loss of fertility in men with varicocele. Fertil Steril. 1993;59:613-616.

9 Witt MA, Lipshultz LI. Varicocele: A progressive or static lesion? Urology. 1993;42:541-543.

10 World Health Organization. The influence of varicocele on parameters of fertility in a large group of men presenting to infertility clinics. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:1289-1293.

11 Jarow JP, Ogle SR, Eskew LA. Seminal improvement following repair of ultrasound detected subclinical varicoceles. J Urol. 1996;155:1287-1290.

12 Steckel J, Dicker AP, Goldstein M. Relationship between varicocele size and response to microsurgical ligation of the spermatic veins. J Urol. 1993;149:769-771.

13 Zorgniotti AW, MacLeod J. Studies in temperature, human semen quality, and varicocele. Fertil Steril. 1973;24:854-863.

14 Tanji N, Tanji K, Hiruma S, et al. Histochemical study of human cremaster in varicocele patients. Arch Androl. 2000;45:197-202.

15 Ozbek E, Yurekli M, Soylu A, et al. The role of adrenomedullin in varicocele and impotence. BJU Int. 2000;86:694-698.

16 Kass EJ, Chandra RS, Belman AB. Testicular histology in the adolescent with a varicocele. Pediatrics. 1987;79:996-998.

17 Su LM, Goldstein M, Schlegel PN. The effect of varicocelectomy on serum testosterone levels in infertile men with varicoceles. J Urol. 1995;154:1752-1755.

18 Dubin L, Amelar RD. Varicocelectomy: 986 cases in a 12 year study. Urology. 1977;10:446-449.

19 Nieschlag E, Hertle L, Fischedick A, et al. Update on treatment of varicocele: Counseling as effective as occlusion on the vena spermatica. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:2147-2150.

20 Madgar I, Weissenberg R, Lunenfeld B, et al. Controlled trial of high spermatic vein ligation for varicocele in infertile men. Fertil Steril. 1995;63:120-124.

21 Jaffe T, Oates RD. Genetic abnormalities and reproductive failure. Urol Clin North Am. 1994;21:389-408.

22 Phillipson G. Cystic fibrosis and reproduction. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1998;10:113-119.

23 Mulhall JP, Reijo R, Alagappan R, et al. Azoospermic men with deletion of the DAZ gene cluster are capable of completing spermatogenesis: Fertilization, normal embryonic development and pregnancy occur when retrieved testicular spermatozoa are used for intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:503-508.

24 Oates RD, Silber S, Brown LG, Page DC. Clinical characterization of 42 oligospermic or azoospermic men with microdeletion of the AZFc region of the Y chromosome, and 18 children conceived via ICSI. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2813-2824.

25 Page DC, Silber S, Brown LG. Men with infertility caused by AZFc deletion can produce sons by intracytoplasmic sperm injection, but are likely to transmit the deletion and infertility. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1722-1726.

26 Hendry WF. Disorders of ejaculation: Congenital, acquired and functional. Br J Urol. 1998;82:331-341.

27 Waldinger MD, Hengeveld MW, Zwinderman AH, Olivier B. Effect of SSRI antidepressants on ejaculation: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study with fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;18:274-281.

28 Dunsmuir WD, Holmes SA. The aetiology and management of erectile, ejaculatory, and fertility problems in men with diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 1996;13:700-708.

29 Griffith ER, Tomko MA, Timms RJ. Sexual function in spinal cord-injured patients: A review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1973;54:539-543.

30 Jarow JP, Wright WW, Brown TR, et al. Bioactivity of androgens within the testes and serum of normal men. J Androl. 2005;26:343-348.

31 Knuth UA, Maniera H, Nieschlag E. Anabolic steroids and semen parameters in body builders. Fertil Steril. 1989;52:1041-1047.

32 Howell SJ, Shalet SM. Testicular function following chemotherapy. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7:363-369.

33 Carlsen E, Andersson AM, Petersen JH, Skakkebaek NE. History of febrile illness and variation in semen quality. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2089-2092.

34 Sheiner EK, Sheiner E, Hammel RD, et al. Effect of occupational exposures on male fertility: Literature review. Indust Health. 2003;41:55-62.

35 Burrows PJ, Schrepferman CG, Lipshultz LI. Comprehensive office evaluation in the new millennium. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29:873-894.

36 Ohl DA, Denil J, Bennett CJ, et al. Electroejaculation following retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy. J Urol. 1991;145:980-983.

37 Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Baird DD. Timing of sexual intercourse in relation to ovulation. Effects on the probability of conception, survival of the pregnancy, and sex of the baby. NEJM. 1995;333:1517-1521.

38 Schuster TG, Ohl DA. Diagnosis and treatment of ejaculatory dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29(4):939-948.

39 Rosen RC, Lane RM, Menza M. Effects of SSRIs on sexual function: A critical review. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19:67-85.

40 Kutteh WH, Chao CH, Ritter JO, Byrd W. Vaginal lubricants for the infertile couple: Effect on sperm activity. Int J Fertil Menopausal Studies. 1996;41:400-404.

41 Hershlag A, Cooper GW, Benoff S. Pregnancy following discontinuation of a calcium channel blocker in the male partner. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:599-606.

42 Brugh VM, Matschke HM, Lipshultz LI. Male factor infertility. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2003;32:689-707.

43 Stillman RJ. In utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol: Adverse effects on the reproductive tract and reproductive performance and male and female offspring. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;142:905-921.

44 Sigman M, Jarow JP. Ipsilateral testicular hypotrophy is associated with decreased sperm counts in infertile men with varicoceles. J Urol. 1997;158:605-607.

45 World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination of Human Semen and Sperm–Cervical Mucus Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

46 Jarow JP. Seminal vesicle aspiration of fertile men. J Urol. 1996;156:1005-1007.

47 Mallidis C, Howard EJ, Baker HW. Variation of semen quality in normal men. Int J Androl. 1991;14:99-107.

48 Grow DR, Oehninger S, Seltman HJ, et al. Sperm morphology as diagnosed by strict criteria: Probing the impact of teratozoospermia on fertilization rate and pregnancy outcome in a large in vitro fertilization population. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:559-567.

49 Ohl DA, Naz RK. Infertility due to antisperm antibodies. Urology. 1995;46:591-602.

50 Sharlip ID, Jarow JP, Belker AM, et al. Best practice policies for male infertility. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:873-882.

51 Sokol RZ. Infertility in men with cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulmon Med. 2001;7:421-426.

52 Gregg AR, Simpson JL. Genetic screening for cystic fibrosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2002;29:329-340.

53 Vicdan A, Vicdan K, Gunalp S, et al. Genetic aspects of human male infertility: The frequency of chromosomal abnormalities and Y chromosome microdeletions in severe male factor infertility. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;117:49-54.

54 Hopps CV, Mielnik A, Goldstein M, et al. Detection of sperm in men with Y chromosome microdeletions of the AZFa, AZFb and AZFc regions. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1660-1665.

55 Schlegel PN, Shin D, Goldstein M. Urogenital anomalies in men with congenital absence of the vas deferens. J Urol. 1996;155:1644-1648.

56 McClure RD, Khoo D, Jarvi K, Hricak H. Subclinical varicocele: The effectiveness of varicocelectomy. J Urol. 1991;145:789-791.

57 Gonda RLJr, Karo JJ, Forte RA, O’Donnell KT. Diagnosis of subclinical varicocele in infertility. AJR. 1987;148:71-75.

58 Pryor JP, Hendry WF. Ejaculatory duct obstruction in subfertile males: Analysis of 87 patients. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:725-730.

59 Chan PT, Schlegel PN. Diagnostic and therapeutic testis biopsy. Curr Urol Rep. 2000;1:266-272.

60 Jarow JP. Diagnosis and management of ejaculatory duct obstruction. Tech Urol. 1996;2:79-85.

61 Seifman BD, Ohl DA, Jarow JP, Menge AC. Unilateral obstruction of the vas deferens diagnosed by seminal vesicle aspiration. Tech Urol. 1999;5:113-115.

62 Sokol RZ, Steiner BS, Bustillo M, et al. A controlled comparison of the efficacy of clomiphene citrate in male infertility. Fertil Steril. 1988;49:865-870.

63 Siddiq FM, Sigman M. A new look at the medical management of infertility. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29:949-963.