214 Ethics of Resuscitation

• Resuscitation colloquially comprises a spectrum of care that includes intravenous fluids, oxygen, cardiac pressors, and antibiotics.

• Cardiac arrest is the moment of death, when cardiac or respiratory effort ceases. Noninitiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in the event of death is called “natural death.”

• In the event of cardiac arrest, CPR is universally presumed unless patients have previously expressed a desire to be treated otherwise.

• The ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice must be considered in discussions regarding resuscitation.

• Emergency physicians (EPs) should be prepared to guide patients and families in the recommendation regarding initiation of CPR in the event of cardiac arrest based on goals of care. EPs should also be able to discuss the usual outcomes of cardiac arrest in terms of survival and disability and be comfortable describing nonresuscitation as “natural death.”

• When discussing prognoses in patients with a chronic progressive medical illness, it may be helpful to explain that the best medical outcome that can be hoped for is that the patient returns to his or her “baseline status” or condition before admission.

• EPs should be able to recognize and treat the syndrome of imminent death and provide comfort measures regardless of the initiation of CPR.

Perspective

Patient autonomy, nonmaleficence (doing no harm), beneficence (promoting good or well-being), and justice (being fair) are the guiding principles of medical ethics.1 For a patient to make autonomous decisions about resuscitation preferences, the patient (or designated medical decision maker) should be given the best information available to weigh his or her medical care options. The Jonsen model for ethical decision making suggests that the following four “ethical quadrants” be weighed: medical indications, patient preferences, quality of life, and contextual features.2

Despite much debate and discussion, medicine and society have not been able to agree on a common and accepted definition of the term medical futility.3 One suggested paradigm of medical futility characterizes a medical intervention as futile when its goal will not probably be achieved.3 Although one common medical goal of clinicians who perform CPR after cardiac arrest is return of spontaneous circulation, the patient, surrogate, and clinician may have other equally important goals, including neurologic outcome and quality of life after resuscitation. Timely discussion between the clinician and the patient or his or her designated decision maker regarding the goals of care is paramount to ensure quality end-of-life care.

Noninitiation of CPR is increasingly being described as “allow natural death.” It is of utmost importance for clinicians to understand that before CPR, a host of interventions may be used to extend life but, in the event of death, the option may be to not attempt CPR. For example, research suggests that in cancer patients for whom all aggressive interventions (antibiotics, fluids, pressors, airway support) have been tried, in the event of death the success of CPR in achieving survival to discharge is zero.4

Epidemiology

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) has an incidence of 52.1 per 100,000 population, which makes it the third leading cause of death in North America.5 The survival rate of patients experiencing OHCA after treatment by emergency medical services is approximately 8%, but it varies widely among regions.5 For patients who suffer in-hospital pulseless cardiac arrest, survival to hospital discharge depends widely on the characteristics of the arrest and patient comorbid conditions (Table 214.1). Research suggests that when talking with patients, physicians can describe the overall likelihood of survival to discharge as 1 in 8 for patients who undergo CPR and 1 in 3 for patients who survive CPR.6 Many of the patients who survive to discharge will be discharged to institutionalized settings. Poor prognostic indicators of survival after cardiac arrest include cancer, dementia, sepsis, cardiac disease, elevated serum creatinine, and African American race.6 Despite these well-publicized numbers in the medical literature, EPs should be aware that patients and their families may have very different expectations of resuscitative efforts after cardiac arrest. Popular U.S. television programs, for example, incorrectly suggest that the immediate survival rate after cardiac arrest approaches 75%, with 67% of patients being portrayed as surviving to hospital discharge.7

Table 214.1 Survival After In-Hospital Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation*

| Incidence of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation | 2.73 events per 1000 admissions |

| Incidence higher for nonwhite patients |

* Medicare data from 1992 to 2005 involving 433,895 cases of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in patients 65 years or older.

Data from Ehlenbach WJ, Barnato AE, Curtis JR, et al. Epidemiologic study of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the elderly. N Engl J Med 2009;361:22–31.

Pathophysiology

Cardiac arrest is the sudden, abrupt loss of heart function.8 The most common underlying reason for patients to die suddenly after cardiac arrest is coronary heart disease. Most cardiac arrests that lead to sudden death occur as a result of arrhythmias such as ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation. A patient’s chances of survival after cardiac arrest are reduced by 7% to 10% with every minute that passes without CPR and defibrillation. Few attempts at resuscitation succeed after 10 minutes.8

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

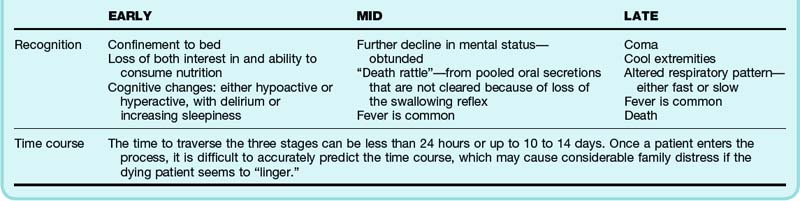

One classic scenario illustrating many of the ethical dilemmas surrounding resuscitation is a patient who arrives at the ED critically ill with possible impending cardiac arrest or with signs of active dying (Table 214.2). Decisions must be made quickly regarding which life-extending measures will be used while also simultaneously ensuring relief of patient distress. If a patient is likely to deteriorate rapidly or shows signs of imminent death, a discussion regarding resuscitation should be initiated with the patient or the appropriate surrogate. The EP should make a clinical assessment that includes evaluation of the goals of care, determination of the presence or absence of an advance directive, and a recommendation regarding the utility of CPR to meet the patient’s goals of care. Table 214.2 lists the signs of active dying in the setting of a chronic progressive incurable illness, such as late-stage cancer, dementia, or failure to thrive.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Patients or their medical decision makers who choose to forgo measures such as CPR may also, but not necessarily, choose a more global comfort approach to their end-of-life care. The EP should be able to provide palliative measures and support this comfort care (Table 214.3). It is important to recognize, however, that these patients may still need intensive in-hospital care. In some cases, transfer of a patient from the emergency department to a hospice may be possible. More often, patients are admitted to the hospital and may require temporary intensive care to assess the goals of care and adequately achieve comfort. For a patient who is undergoing advanced life support measures, such as invasive ventilation and cardioactive drugs, a time-limited trial may help the patient and his or her family feel more comfortable delineating the goals of care.

| Clearly define the goals of treatment | Once imminent death is recognized, discuss with family and confirm the treatment goals. When assuming a comfort approach, make a supportive statement, such as “You are doing the right thing.” |

| Discuss with family stopping interventions that do not contribute to comfort. | |

| Provide good palliative care | To contral oral/respiratory secrections (“death cattle”), use antimuscarinic blockers such as glycopyrrolate, 0.2 mg intravenously (onset, 1 min); atropine, 0.1 mg intravenously (onset, 1 min); atropine eyedrop 1%, 2 drops sublingually (onset, 30 min); or hyoscyamine hydrobromide, 1.5 mg transdermally (onset, 12 hr). |

| Use morphine (1-2 mg IV/SC every 5 min or 5 mg orally every 1 hr as starting dose) to control dyspnea or tachypnea. It can be very disturbing for family members to see loved ones in a coma breathing at 40 breaths/min. The goal should be to keep the respiratory rate in the range of 10 to 15 breaths/min. | |

| Provide excellent mouth and skin care. | |

| Determine disposition | According to symptom burden, patients may require assignment to the intensive care unit to ensure that the treatment goals remain on target and that the medical aspects of palliative care are met (control of pain and dyspnea, for example) despite a “do-not-resuscitate” status. |

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics, 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Ehlenbach WJ, Barnato AE, Curtis JR, et al. Epidemiologic study of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:22–31.

Ewer MS, Kish SK, Martin CG, et al. Characteristics of cardiac arrest in cancer patients as a predictor of survival after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Cancer. 2001;92:1905–1912.

Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ. Clinical ethics: a practical approach to ethical decisions in clinical medicine. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2010.

Nichol G, Thomas E, Callaway CW, et al. Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. JAMA. 2008;300:1423–1431.

1 Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics, 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008.

2 Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ. Clinical ethics: a practical approach to ethical decisions in clinical medicine, 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2010.

3 Lofmark R, Nilstun T. Conditions and consequences of medical futility—from a literature review to a clinical model. J Med Ethics. 2002;28:115–119.

4 Ewer MS, Kish SK, Martin CG, et al. Characteristics of cardiac arrest in cancer patients as a predictor of survival after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Cancer. 2001;92:1905–1912.

5 Nichol G, Thomas E, Callaway CW, et al. Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. JAMA. 2008;300:1423–1431.

6 Ebell MH, Becker LA, Barry HC, et al. Survival after in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:805–816.

7 Diem SJ, Lantos JD, Tulsky JA. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation on television: miracles and misinformation. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1578–1582.

8 . American Heart Association 2011. Available at http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=4481 Accessed February 21, 2011