Chapter 204 Ethical and Medicolegal Aspectsof Spine Surgery

Patients—Our Primary Responsibility

We also gain wisdom from reading literature generated by our subspecialty discipline, as well as other disciplines. Review of contemporary textbooks, monthly reading of our society-specific journals, and, in particular, the study of evidence-based medicine guidelines1,2 add to our growing, maturing knowledge base. From a technical standpoint, do not assume that because you operate three days a week, your technical skills are at their peak. Do not forget the merits of cadaveric anatomic dissections. Learn new techniques or modifications through cosurgeon mentoring experiences or through additional didactic tutoring, including formal fellowship training.

New knowledge needs to be pursued throughout one’s lifetime. Reading and writing are certainly part of this process, as are teaching and mentoring. A dedication to lifelong learning must be carried on during one’s professional career. Scientific inquiry, either in the laboratory or from clinical practice (clinical outcomes analysis) fortifies this effort. Sharing professional experiences with others by way of consultations, conferences, presentations, and societal meetings serves this purpose. Seek advice from those who have trained and/or think differently than you do. On the one hand, seek the advice of independent thinkers and actors, yet appreciate the concept of the “wisdom of the crowd” as defined by James Surowecki: “In the right circumstances, large groups of people are smarter than an elite few, no matter how brilliant—better at solving problems, fostering innovation, coming to wise decisions, even predicting the future.”3

Familiarize yourself with the concept of metacognition, which is defined as higher-order thinking that involves active control over the cognitive processes engaged in learning.4 One of the key tenets in the ability to control or regulate one’s cognitive processes is a thoughtful self-assessment and appreciation of one’s knowledge base and deficits. Attempt to identify your professional biases and blind spots. In addition to reading about what you know or believe in (a good thing), read about or study less familiar topics and professional areas.

Treat patients with compassion. Be thoughtful and respectful. Patients already know that you are smart, you are an expert, and you are very busy, typically well behind schedule. Offer them caring consideration for the periods of time in which you interact with them. Try to avoid characterizing them or dismissing them or their issues at the outset. Take the time to greet each patient and look him or her in the eyes. Remember the advice of Sir William Osler: “Care more for the individual patient than for the special features of the disease … put yourself in his place … the kindly word, the cheerful greeting, the sympathetic looks … these the patient understands.”5

Your patients will have completed information sheets while they waited for you. Your staff, nurse, or resident will have interviewed and examined patients before you meet them. Sit down at the patient’s height, and review the clinical information that has already been collected. Discuss the highlights of the patient’s complaints. After washing your hands, examine each patient yourself. Yours may be a focused examination, but it is the most expert (or should be if you are attentive), and it is what the patient both expects and deserves. Osler’s adage is insightful: “The value of experience is not in seeing much, but in seeing wisely.”5 Thoughtfully study the patient’s images or other diagnostic studies, and review them with the patient. Offer your learned interpretation. If it is at odds with the radiologist’s report, simply explain your interpretation without becoming defensive or derogatory toward the alternative interpretation. You are trained to be a spine surgeon, but more important, you are trained to evaluate and sort out those patients who are likely to benefit from your surgical skills. You have taken an oath to be responsible to your profession and the patients you will encounter.

Conversely, do not adopt a “do something, do anything” approach. There are some patients for whom surgery is not indicated or wise when all aspects are considered. For example, many patients with metastatic oncologic disease affecting the spinal column will not survive beyond 6 months, irrespective of the treatment you offer. Similarly, carefully selected patients who have persistent back pain after initial spine surgery will benefit from a spine fusion procedure, but most will not. Be judicious and appropriate in the application of your surgical expertise. And, as discussed later, remember to make informed consent a process through which you explain, discuss, and maintain an environment in which you present and outline the risks, benefits, and alternatives that are available to the patient.1

Use common sense when making patient management decisions. Common sense is the balance of your knowledge, your experience, the literature, your morality and personal integrity, your professional commitment, your emotions, your beneficence, and your compassion. Weigh all of the features and factors of a patient’s predicament. Analyze all of the issues and considerations, and decide what strategy or what combination of strategies makes the most sense for the patient. Distinguish between your desire to help the patient and your ability to help the patient. (This works both ways: Sometimes clinicians do not want to help but are able to do so. Such a situation borders on negligence. At other times, the clinician might wish to help but cannot, or no attempt to help makes any sense.) Determine which approach, if any, is the most ideal and the most likely to give the patient real and meaningful benefit. Importantly, do not fail to engage in a patient’s care because it inconveniences you, because it conflicts with your social schedule, or for financial, political, or other reasons. We do not suggest that you should become a “super doctor,” diagnosing and treating patients who have maladies that are beyond your professional focus. You are gifted, however. Strive to be the best. Make the diagnosis that others have not made or cannot make, and offer the patient advice and an appropriate referral. As Osler urges, “The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.”5 Whatever decisions you do make on the patient’s behalf, communicate them effectively and with compassion to the patient.

Professional Responsibility

Respect, honor, and revere the values and principles of our profession. Patients are our first professional priority; our discipline and profession are our second. Recall the Hippocratic Oath, in both the modern and original versions6 (Boxes 204-1 and 204-2). Live your professional life by them.

• Be the best spine surgeon you can be, both with respect to clinical evaluation (diagnosis) and surgical expertise (technical skills). Maintain and upgrade your knowledge and skills over time.

• Respect each and every patient, their privacy, their bodies, their emotions, and their dignity. Your interactions and discussions are confidential. Learn to sense your patient’s worries and fears; be sensitive and address and allay them if you are able.

• Never subject a patient to a procedure (diagnostic or therapeutic) that has little chance of benefit (use evidence-based medicine to help you decide) or that is unnecessary. (An example of the former is intradiscal thermal therapy, a procedure for which you can bill but that is associated with little, if any, medical evidence of meaningful benefit over time. An example of the latter is the routine practice of obtaining myelography on patients who already have definitive MRI studies, a significant source of income for some practicing spine surgeons to this day.).

• Never provide an assessment, offer an opinion, or perform a procedure when you are cognitively or physically impaired (regardless of whether you might be discovered). Your patient expects and deserves your best. You are not at your best following injury, during a significant medical illness, or when you are under the influence of alcohol or other intoxicants. Similarly, do not allow yourself to become distracted in the operating room (OR) during your procedure, whether watching a key ball game on television, listening to distracting music, telling lengthy jokes or stories, or interacting inappropriately with the OR staff.

• Identify with your patients and their troubles, but do not cross the physician–patient relationship barrier either for presumed affection (their willing participation) or your perversion (their forced participation). Maintain an appropriate, respectful, professional relationship with patients and their family members.

• Do not experiment on your patients. Yes, within sound limits, you can improvise as necessary during surgery, using your skills and experience to avoid or treat a complication or to perform or complete a procedure beyond that which you had planned at the outset. Yes, you can offer new therapies and use new devices in the management of your patients, but three things must occur first:

• Maintain your professional standing and licensure with timely renewal. Participate in quality assessment and peer review in your institution. Engage in lifelong learning and your specialty board Maintenance of Certification process throughout your professional career.

BOX 204-1 Hippocratic Oath: Modern Version

I swear to fulfill, to the best of my ability and judgment, this covenant:

Written in 1964 by Louis Lasagna, Academic Dean of the School of Medicine at Tufts University. Available at www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/body/hippocratic-oath-today.html#modern.

BOX 204-2 Hippocratic Oath: Classical Version

I swear by Apollo Physician and Asclepius and Hygieia and Panaceia and all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will fulfill according to my ability and judgment this oath and this covenant:

To hold him who has taught me this art as equal to my parents and to live my life in partnership with him, and if he is in need of money to give him a share of mine, and to regard his offspring as equal to my brothers in male lineage and to teach them this art—if they desire to learn it—without fee and covenant; to give a share of precepts and oral instruction and all the other learning to my sons and to the sons of him who has instructed me and to pupils who have signed the covenant and have taken an oath according to the medical law, but no one else.

I will apply dietetic measures for the benefit of the sick according to my ability and judgment; I will keep them from harm and injustice.

I will neither give a deadly drug to anybody who asked for it, nor will I make a suggestion to this effect. Similarly, I will not give to a woman an abortive remedy. In purity and holiness I will guard my life and my art.

I will not use the knife, not even on suffers from stone, but will withdraw in favor of such men as are engaged in this work.

Whatever houses I may visit, I will come for the benefit of the sick, remaining free of all intentional injustice, of all mischief and in particular of sexual relations with both female and male persons, be they free or slaves.

What is may see or hear in the course of the treatment or even outside of the treatment in regard to the life of men which on no account one must spread abroad, I will keep to myself, holding such things shameful to be spoken about.

If I fulfill this oath and do not violate it, may it be granted to me to enjoy life and art, being honored with fame among all men for all time to come; if I transgress it and swear falsely, may the opposite of all this be my lot.

Translation from the Greek by Ludwig Edelstein. From Edelstein L: The Hippocratic Oath: text, translation, and interpretation, Baltimore, 1943, Johns Hopkins Press. Available at www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/body/hippocratic-oath-today.html#classical.

Sir William Osler offered sage advice about our personal integrity and our professional careers: “The greatest leverage you can create for yourself is the pain that comes from inside, not outside. Knowing that you have failed to live up to your own standards for your life is the ultimate pain. If we fail to act in accordance with our own view of ourselves, if our behaviors are inconsistent with our standards—with the identity we hold for ourselves—then the chasm between our actions and who we are drives us to make changes. One of the strongest forces in the human personality is the drive to preserve the integrity of our own identity.”5

Box 204-3 summarizes the most important things to remember for successful surgical management.

BOX 204-3 Keys to Successful Clinical Surgical Management

• Be personable and professional.

• Give the impression that you have time and are not in a hurry.

• Demonstrate sensitivity and concern.

• Review the patient history (be sure it is accurate), perform the key elements of the examination (make contact with the patient), and review the images with the patient.

• Explain yourself; make an effort to be understood. Avoid using medical terms and jargon.

• Do not rush to surgery unless it is truly indicated.

• Failure to respond to medical treatment.

• The more patient–physician interactions, the better the relationship.

• Obtain and document informed consent.

• Greet each patient and family before surgery.

• Provide and document expert surgical care in the operating room. You are the surgical team leader.

• Call the family after the operation.

• See your patients on rounds at least daily while they are hospitalized, preferably twice daily.

• Have a timely, responsive paradigm for postoperative attention and assessment.

Minimizing Litigation Risk

Given all of these possibilities, consider the following ideas to establish and improve the doctor–patient relationship and hence to foster more effective communication and better care. Take time to greet patients and the family members who accompany them. Introduce yourself by your given name (e.g., “Mark Hadley,” not “Dr. Hadley”) and smile at them. Sit down. Do your best to record and recall their first names and where they are from. Try (in a short time) to appear friendly, relaxed, as humble as possible, and not rushed (giving them whatever time they need). Apologize for being late or behind schedule (most will appreciate this). Interact with them as if they were family members, dear friends, or neighbors whom you are counseling on your backyard patio. Be mindful of any barriers in language or culture.11 Do not discourage questions. After the chat and interview, get up, wash your hands, and perform the essential elements of the examination yourself (put your hands on the patient). Spend time and review the images, explaining your interpretation without criticism of the radiologic interpretation or any poor work that was completed or attempted. In conclusion, offer your diagnosis and a treatment plan. Again, answer questions that arise. For patients with a diagnosis that you do not specifically treat, offer the appropriate referral. Above all, do your best to explain yourself and your thinking, and offer a potential treatment.12 Stay calm, even if the patient or family members challenge or attempt to provoke you.

Do not offer surgery based on imaging (exceptions may be trauma, instability, or cancer). Rarely will you see a patient in the clinic who truly needs an urgent procedure. Discuss medical management, and when appropriate, send the patient away to pursue it. Patients should leave your clinic with a follow-up appointment if surgery is an option, should medical treatment fail. Patients typically do not want surgery. Most favor a comprehensive attempt at medical treatment before they will consider surgery. Failure to first exhaust medical therapy can be an extremely contentious medicolegal topic if your patient just meets you, goes straight to surgery, and has a poor outcome.13 The more interactions you have with a patient before a surgical procedure, the better the patient can get to know you and form a favorable personal impression.

From a medicolegal perspective, when a bad outcome occurs, patients are far more likely to consider legal action against the unknown, aloof, surgical “expert” than against a surgeon they have come to know, who has made an effort to understand them, and whom they like and and respect.13 While one cannot successfully win a suit only because the surgeon “acted like a jackass,” the “jackass” surgeon is much more likely to get sued in the event of a poor outcome.

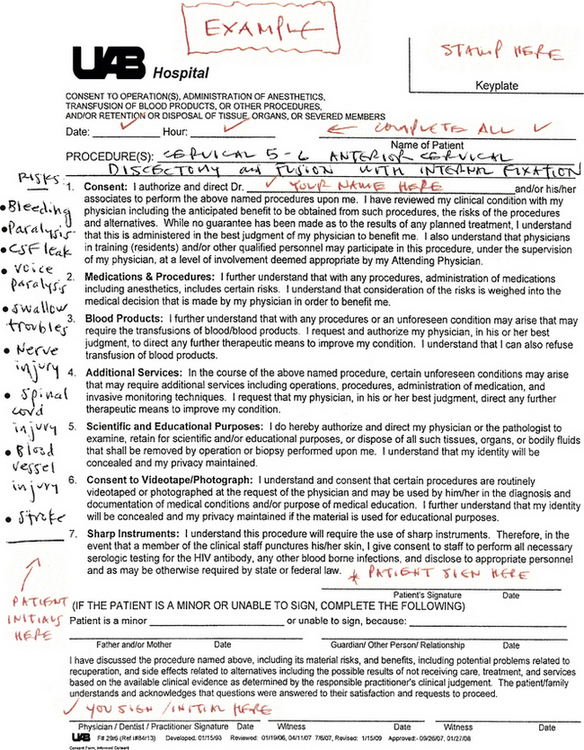

Obtain appropriate informed consent. This is a topic that could, and does, fill many articles and books; it is of central importance. After your examination, and after the establishment of a plan of care, if a procedure is called for, remember that informed consent is a process.7 It should include notes in the clinical chart that reflect your conversations with the patient. In these conversations, you should describe the essential elements of the operative procedure to be performed. Offer a rough idea about how long the procedure will take to complete once the patient is asleep and positioned. Describe the potential complications associated with the operative procedure (e.g., difficulty swallowing and/or speaking, hoarseness, fluid collection or blood clot, cerebrospinal fluid leak, arterial injury, nerve injury, and/or spinal cord injury are possible complications for an anterior cervical discectomy and fusion procedure). On the other hand, you do not need to spend time reviewing every possible complication or every potential anesthetic complication, but do not shy away from potentially major adverse risks, including death, paralysis, or stroke. Honestly describe your experience with the specific procedure over the course of your career, using general terms. Specifically write the name of the procedure on the consent form, and in the margin, handwrite a list of major potential complications. Invite questions. Patients must sign the consent form and initial the list of the potential complications on the form. You should sign the form as well (Fig. 204-1).

Informed consent has long been a major topic of debate. Patients and family don’t often recall the details of the informed consent discussion.14 They argue that the preprinted forms are too long, too hard to read, too confusing, and too much like a business contract that they signed without reading or fully understanding. Specifically writing the procedure description and creating a list of potential complications associated with the procedure in the margin in ink and having the patient sign and initial it can diffuse a great number of these arguments should questions be raised following a poor outcome.

Greet each patient and his or her family in the preoperative holding area as they present on the day of their scheduled surgery. Shake hands and use the first names of the patient and the spouse or other family member(s) present. Remind them that you are present, fit, and committed to doing your very best. Mark their surgical site yourself; remind yourself of the procedure you have proposed, including side and level. Smile and show both compassion and optimism. (This is yet another important opportunity to calm and bond with the patient, to show your personal attachment and humanity.)

Do not hide behind an “I don’t know” excuse; on the other hand, do not speculate if the cause of the event is indeed uncertain.15 Do not abandon the patient. See more often and spend more time with patients who have unexpected outcomes or complications. Too often, surgeons distance themselves from patients who have experienced a complication. This confuses the patient and family and leads to questions about the surgeon’s professionalism, character, commitment, and expertise. If you have a patient with an untoward result, it is far better to have his or her family members know that the surgeon did all he or she could, spent more time rather than less, truly cared about the patient, and regretted the bad outcome.

Think twice before criticizing other physicians and surgeons who may have advised or treated the patient before you. Rarely are you going to have all of the facts necessary to render a fully informed opinion about prior care. Resist the natural human response of appearing astounded over a patient’s plight and treatment. Patients do not always describe the physician–patient interaction in the same way the physician would. What a patient reports to you about the other doctor’s words, actions, and deeds might not be entirely accurate. You were not present during those earlier interactions. You were not asked to provide an opinion on the patient earlier, before the current circumstances. Assess the patient’s present status without criticism. Do not add fuel to the fire, and resist the urge to be a “Monday morning quarterback.” Recall with humility that all clinicians (you included) have patients who have not been helped as intended or hoped.

A number of professional organizations have attempted to address this issue. Recommendations and guidelines have been generated16 (Box 204-4). We would advise you to avoid the temptation of undertaking this “work” simply for the extra income it might offer; doing so produces incentives that are at odds with rigorous adherence to the guidelines and our duties to patients and the legal system. Instead, follow your professional common sense, vigorously maintain your adherence to the guidelines’ protocols, and serve as an expert when you find a truly compelling, ethical reason to become engaged.

BOX 204-4 Congress of Neurological Surgeons’ Guidelines on Physician Expert Witness Activity and Testimony

I Qualifications for the Physician Expert Witness in Neurologic Surgery

A. The neurosurgeon expert witness must have a current, valid, and unrestricted license to practice medicine in the state in which he or she practices.

B. The neurosurgeon expert witness should be a diplomate of the American Board of Neurological Surgery or have status with a specialty board recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties.

C. The specialty of the neurosurgeon expert witness should be appropriate to the subject matter of the case. He or she should be qualified by experience and should have demonstrated competence in the subject of the case.

D. The neurosurgeon expert witness should be familiar with the standard of care provided at the time of the alleged occurrence and should be actively involved in the clinical practice of the specialty or the subject matter of the case during the time the testimony or opinion is provided.

E. The neurosurgeon expert witness should be able to demonstrate evidence of continuing medical education relevant to the specialty or the subject matter of the case.

F. The neurosurgeon expert should be prepared to document the percentage of time that is involved in serving as an expert witness. In addition, the neurosurgeon expert should be willing to disclose the amount of fees or compensation obtained for such activities and the total number of times the neurosurgeon expert has testified for the plaintiff or the defendant.

II Guidelines for Behavior of the Physician Expert Witness in Neurologic Surgery

A. The neurosurgeon expert witness should review the medical information in the case and testify to its content fairly, honestly, and in a balanced manner. In addition, the neurosurgeon expert witness may be called upon to draw an inference or an opinion based on the facts of the case. In doing so, the neurosurgeon expert witness should apply the same standards of fairness and honesty.

B. The neurosurgeon expert witness should be prepared to distinguish between actual negligence (substandard medical care that results in harm) and an unfortunate medical outcome (recognized complication[s] occurring as a result of medical treatment).

C. The neurosurgeon expert witness should review the standards of practice prevailing at the time of alleged occurrence.

D. The neurosurgeon expert witness should be prepared to state the basis of his or her testimony or opinion, and whether it is based on personal experience, specific clinical references, evidence-based guidelines, or a generally accepted opinion in the specialty field. The neurosurgeon expert witness should be prepared to discuss important alternate methods and views.

E. Compensation of the neurosurgeon expert witness should be reasonable and commensurate with the time and effort given to preparing for deposition and court appearance. It is unethical for a neurosurgeon expert witness to link compensation to the outcome of a case.

F. The neurosurgeon expert witness is ethically and legally obligated to tell the truth. Transcripts of depositions and courtroom testimony are public records and subject to independent peer reviews. The neurosurgeon expert witness should be aware that failure to provide truthful testimony exposes the neurosurgeon expert to criminal prosecution for perjury, civil suits for negligence, revocation or suspension of his or her professional license, and/or disciplinary action including censure by the Congress of Neurological Surgeons.

© Congress of Neurological Surgeons, August 20, 2001.

Bernat J., Peterson L. Patient-centered informed consent in surgical practice. Arch Surg. 2006;141:86-92.

BrainyQuote. “William Osler Quotes.”. http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/w/williamosl159326.html.

Hadley M.N., Walters B.C., Grabb P.A., et al. Guidelines for the management of acute cervical spine and spinal cord injuries. Neurosurgery. 2002;50(Suppl 3):S1-S178.

Huntoon M., Levy R. How to keep a bad outcome from becoming a lawsuit. Pain Med. 2008;9:S128-S132.

1. Hadley M.N., Walters B.C., Grabb P.A., et al. Guidelines for the management of acute cervical spine and spinal cord injuries. Neurosurgery. 2002;50(Suppl 3):S1-S178.

2. Resnick D.K., Choudheri T.F., Dailey A.T., et al. Guidelines for the performance of fusion procedures for degenerative disease of the lumbar spine. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:1-740.

3. Surowiecki James. The wisdom of crowds. New York: Doubleday/Random House; 2004.

4. Brown A.L. Metacognition, executive control, self-regulation, and other more mysterious mechanisms. In: Weinert F.E., Kluwe R.H., editors. Metacognition, motivation, and understanding. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1987:65-116.

5. BrainyQuote. “William Osler Quotes.”. http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/w/williamosl159326.html.

6. Tyson P. “The Hippocratic oath today.”. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/doctors/oath_modern.html.

7. Bernat J., Peterson L. Patient-centered informed consent in surgical practice. Arch Surg. 2006;141:86-92.

8. Office for Human Research Protections. “Informed Consent FAQ.”. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/policy/consent/

9. Mirza S.K. Accountability of the accused: facing public perceptions about financial conflicts of interest in spine surgery (editorial). Spine J. 2004;4:491-494.

10. White A.P., Vaccaro A.R., Zdeblick T. Physician-industry relationships can be ethically established, and conflicts of interest can be ethically managed (counterpoint). Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:S53-S57.

11. Chandrika D., Koss R.G., Schmaltz S.P., et al. Language proficiency and adverse events in US hospitals: a pilot study, 2007. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(2):60-67.

12. Fager C.A. Malpractice issues in neurological surgery (editorial). Surg Neurol. 2006;65:416-421.

13. Huntoon M., Levy R. How to keep a bad outcome from becoming a lawsuit. Pain Med. 2008;9:S128-S132.

14. Krupp W., Spanehl O., Laubach W., et al. Informed consent in neurosurgery: patient’s recall of preoperative discussion. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2000;142:233-239.

15. When things go wrong. responding to adverse events: a consensus statement of the Harvard Hospitals. Burlington, MA: Massachusetts Coalition for the Prevention of Medical Errors; 2006.

16. Hadley M.N., (for the Congress of Neurological Surgeons). Guidelines on physician expert witness activity and testimony. Neurosurgery News. 2002;3:5.