Ethical and Legal Implications of Practice

After reading this chapter you will be able to:

Summarize the philosophical foundations of ethics.

Summarize the philosophical foundations of ethics.

Explain what constitutes an ethical dilemma and how such dilemmas arise in health care.

Explain what constitutes an ethical dilemma and how such dilemmas arise in health care.

Describe how professional codes of ethics apply to ethical decision making.

Describe how professional codes of ethics apply to ethical decision making.

Explain how traditional ethical principles are useful in resolving ethical dilemmas.

Explain how traditional ethical principles are useful in resolving ethical dilemmas.

Describe the information that should be gathered before making an ethical decision.

Describe the information that should be gathered before making an ethical decision.

Explain how the systems of civil and criminal law differ.

Explain how the systems of civil and criminal law differ.

Describe what constitutes professional malpractice and negligence.

Describe what constitutes professional malpractice and negligence.

Explain how a respiratory therapist can become liable for wrongful acts.

Explain how a respiratory therapist can become liable for wrongful acts.

List the elements that constitute a practice act.

List the elements that constitute a practice act.

Explain how licensing affects legal responsibility and liability.

Explain how licensing affects legal responsibility and liability.

Describe how changes in health care delivery have shaped the ethical and legal aspects of practice.

Describe how changes in health care delivery have shaped the ethical and legal aspects of practice.

Summarize the basic elements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)

Summarize the basic elements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)

Describe the role of advance directives and living wills in health care.

Describe the role of advance directives and living wills in health care.

Philosophical Foundations of Ethics

Although an in-depth discussion of philosophy is beyond the scope of this chapter, it is important to note that ethics has its origins in philosophy. Philosophy may be defined as the love of wisdom and the pursuit of knowledge concerning humankind, nature, and reality.1 Ethics is one of the disciplines of philosophy, which include ontology (the nature of reality), metaphysics (the nature of the universe), epistemology (the nature of knowledge), axiology (the nature, types, and criteria of values), logic, and aesthetics. Ethics is primarily concerned with the question of how we should act. Although ethics may share common origins with the disciplines of law, theology, and economics, as an applied practice, ethics is clearly different from these disciplines.1 Ethics can be described philosophically as a moral principle that supplements the golden rule and can be summed up by a commitment to “respect the humanity in persons.”2

Ethical Dilemmas of Practice

The approaches used to address ethical issues in health care range from the specific to the general. Specific guidance in resolving ethical dilemmas is usually provided by a professional code of ethics. General approaches involve the use of ethical theories and principles to reach a decision.3

Codes of Ethics

A code of ethics is an essential part of any profession that claims to be self-regulating. The adoption of a code of ethics is one way in which an occupational group establishes itself as a profession. A code may try to limit competition, restrict advertisement, or promote a particular image in addition to setting forth rules for conduct.4

The American Association for Respiratory Care (AARC) has also adopted a Statement of Ethics and Professional Conduct. The current code appears in Box 5-1. This code represents a set of general principles and rules that have been developed to help ensure that the health needs of the public are provided in a safe, effective, and caring manner. Codes for different professions might differ from the code governing respiratory care because they may seek different goals. However, all codes of ethics seek to establish parameters of behavior for members of the chosen profession. Professional codes of ethics often represent overly simplistic or prohibitive notions of how to deal with open misbehavior or flagrant abuses of authority.

Ethical Theories and Principles

Ethical theories and principles provide the foundation for all ethical behavior. Contemporary ethical principles have evolved from many sources, including Aristotle’s and Aquinas’ natural law, Judeo-Christian morality, Kant’s universal duties, and the values characterizing modern democracy.5,6 Although controversy exists, most ethicists agree that autonomy, veracity, nonmaleficence, beneficence, confidentiality, justice, and role fidelity are the primary guiding principles in contemporary ethical decision making.1,5

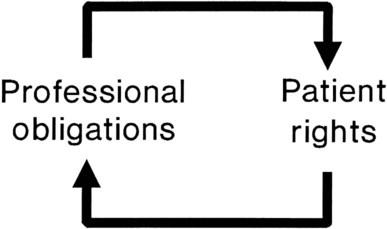

Each of these ethical principles, as applied to professional practice, consists of two components: a professional duty and a patient right (Figure 5-1). The principle of autonomy obliges health care professionals to uphold the freedom of will and freedom of action of others. The principle of beneficence obliges health care professionals to further the interests of others either by promoting their good or by actively preventing their harm. The principle of justice obliges health care professionals to ensure that others receive what they rightfully deserve or legitimately claim.

Veracity

When the physician decides to withhold the truth from a conscious, well-oriented adult, the decision affects the interactions between health care providers and the patient and has a chilling effect on the rapport that is so necessary for good care. In a poll conducted by the Louis Harris group, 94% of Americans surveyed indicated that they wanted to know everything about their cases, even the dismal facts. Other than with pediatrics and rare cases in which there is evidence that the truth would lead to a harm (e.g., suicide), the truth, provided in as pleasant a manner as possible, is probably the best policy.7

Nonmaleficence

The principle of nonmaleficence obligates health care providers to avoid harming patients and to prevent harm actively where possible. It is sometimes difficult to uphold this principle in modern medicine because in many cases drugs and procedures have secondary effects that may be harmful in varying degrees. For example, an RT might ask whether it is ethical to give a high dose of steroids to an asthmatic patient, knowing the many harmful consequences of these drugs. One solution to these dilemmas is based on the understanding that many helping actions inevitably have both a good and a bad effect, or double effect. The key is the first intent. If the first intent is good, the harmful effect is viewed as an unintended result. The double effect brings us to the essence of the definition of the word dilemma. The word comes from the Greek terms di, meaning “two,” and lemma, meaning “assumption” or “proposition.”8

Beneficence

In these cases, some individuals interpret the principle of beneficence to mean that they must do everything to promote a patient’s life, regardless of how useful the life might be to that individual. Other professionals in the same situation might believe they are allowing the principle to be better served by doing nothing and allowing death to occur without taking heroic measures to prevent it. In an attempt to allow patients to participate in resolving this dilemma, legal avenues, called advance directives, have been developed.9 Advance directives allow a patient to give direction to health care providers about treatment choices in circumstances in which the patient may no longer be able to provide that direction. The two types of advance directives available at the present time and widely used are the living will and the durable power of attorney for health care. A durable power of attorney for health care allows the patient to identify another person to carry out his or her wishes with respect to health care, whereas a living will states a patient’s health care preferences in writing. As a result of the Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990, most states require that all health care agencies receiving federal reimbursement under Medicare/Medicaid legislation provide adult clients with information on advance directives.9,10

Confidentiality

The principle of confidentiality is founded in the Hippocratic Oath; it was later reiterated by the World Medical Association in 1949. It obliges health care providers to “respect the secrets which are confided even after the patient has died.”11 Confidentiality, as with the other axioms of ethics, must often be balanced against other principles, such as beneficence.

Confidentiality is usually considered a qualified, rather than an absolute, ethical principle in most health care provider–patient relationships. These qualifications are often written into codes of ethics. The American Medical Association Code of Ethics, Section 9, provides the following guidelines: “A physician may not reveal the confidences entrusted to him in the course of medical attendance or the deficiencies he may observe in the character of patients, unless he is required to do so by law or unless it becomes necessary in order to protect the welfare of the community or a vulnerable individual.” Under the requirements of public health and community welfare, there is often a legal requirement to report such things as child abuse, poisonings, industrial accidents, communicable diseases, blood transfusion reactions, narcotic use, and injuries caused with knives or guns.12 In many states, child abuse statutes protect the health care practitioner from liability in reporting even if the report should prove false as long as the report was made in good faith. Failure to report a case of child abuse can leave the practitioner legally liable for additional injuries that the child may sustain after being returned to the hostile environment.

Despite medical and sociologic advances, potential violations of the individual’s right to privacy in certain populations, such as patients with AIDS, pose a special risk because disclosure may result in economic, psychologic, or physical harm to the patient. RTs would do well to adhere to the dictum found in the Hippocratic Oath: “What I may see or hear in the course of the treatment or even outside of treatment of the patient in regard to the life of men, which on no account one must spread abroad, I will keep to myself, holding such things to be shameful to be spoken about.”13

Justice

A second form of justice seen in health care is compensatory justice. This form of justice calls for the recovery for damages that were incurred as a result of the action of others. Damage awards in civil cases of medical malpractice or negligence are examples of compensatory justice. Compensatory justice has often been cited as playing a major role in increasing the cost of health care. However, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that less than 2% of the cost of health care is related to medical malpractice. Studies by Zurich Insurance Company,14 Harvard University, and Dartmouth University showed little to no impact on the cost of health care and generally debunk the myth that physicians always practice defensive medicine. The Harvard study showed that patients were uncompensated in the presence of actual malpractice more frequently than physicians were held accountable in the absence of actual malpractice. Other studies generally confirm that the civil justice system does a good job of protecting the rights of health care workers and patients in negligence litigation.

Role Duty

Because no single individual can be solely responsible for providing all of a patient’s health care needs, modern health care is a team effort by necessity. There are more than 100 allied health professions, and allied health workers (excluding nursing and physicians) provide about 60% of all patient care. Each of the allied health professions has its own practice niche, defined by tradition or by licensure law. Practitioners have a duty to understand the limits of their role and to practice with fidelity. For example, because of differences in role duty, an RT might be ethically obliged not to tell a patient’s family how critical the situation is, instead having the attending physician do so.3 The previous Mini Clinis addressed role duty, and the accompanying Mini Clini presents another example of the ethics of role duty.

Ethical Viewpoints and Decision Making

In deciding ethical issues, some practitioners try to adhere to a strict interpretation of one or more ethical principles, such as those just described. Other practitioners seek to decide the issue solely on a case-by-case basis, considering only the potential good (or bad) consequences. Still other practitioners would appeal to the image of a “good practitioner,” asking themselves what a virtuous person would do in a similar circumstance. Finally, many practitioners acknowledge that they largely follow their intuition for making ethical decisions. These different viewpoints represent the four dominant theories underlying modern ethics.5,15 The viewpoint that relies on rules and principles is called formalism, or duty-oriented reasoning. The viewpoint in which decisions are based on the assessment of consequences is called consequentialism. The viewpoint that asks what a virtuous person would do in a similar circumstance is called virtue ethics. When intuition is involved in the decision-making process, the approach is called intuitionism.

Virtue Ethics

According to this perspective, the established practices of a profession can give guidance, without an appeal to either the specific moral principles or the consequences of an act.3 When the professional is faced with an ethical dilemma, he or she need only envision what the “good practitioner” would do in a similar circumstance. It is hard to imagine the good RT stealing from the patient, charging for services not provided, or smothering a patient with a pillow.

In addition to the difficulty with changing values in virtue ethics, it provides no specific directions to aid decision making. The heavy reliance of virtue ethics on experience rather than on reason makes creative solutions less likely. Finally, practitioners often find themselves in conflicting role situations for which virtue ethics has no answers. A good example is an RT who practices the virtue of being a good team player but is confronted with the need to “blow the whistle” on a negligent or incompetent team member.3 Despite these limitations, virtue ethics is probably the way most practitioners make their ethical decisions.

Intuitionism

Intuitionism is an ethical viewpoint that holds that there are certain self-evident truths, usually based on moral maxims such as “treat others fairly.” The easiest way to understand intuitionism is to think of as many timeless maxims as you can, which form the basis for intuitionism. These maxims may range from “do not kill” to “look before you cross the street.”6 As a decision-making tool, intuitionism is unhelpful in large measure because it depends on the intuitional abilities of the specific caregiver.

Comprehensive Decision-Making Models

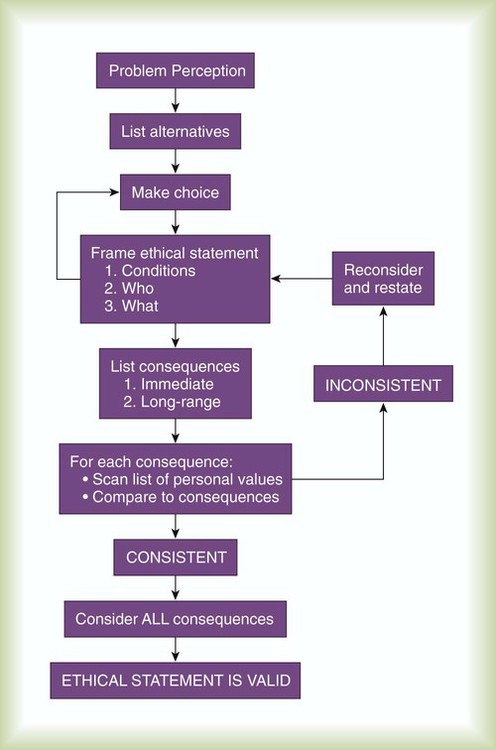

To aid in the process of decision making in bioethics, several comprehensive models have been developed. Figure 5-2 depicts one example of a comprehensive decision-making model that combines the best elements of formalism, consequentialism, and virtue ethics. As is evident in this approach, the ethical problem is framed in terms of the conditions and who is affected. Initially, an action is chosen based on its predicted consequences. The potential consequences of this decision are compared with the human values underlying the problem. The short test of this comparison is a simple restatement of the golden rule that is, “Would I be satisfied to have this action performed on me?” The initial decision is considered ethical if, and only if, it passes this test of human values. A simpler but nonetheless comprehensive model is used by many ethicists. The model uses eight key steps (Box 5-2).

Legal Issues Affecting Respiratory Care

Systems of Law

Civil Law

Tort Law

Professional Negligence

In negligence cases, the breach of duty often involves the matter of foreseeability. Cases in which the patient falls, is burned, is given the wrong medication, or is harmed by defects in an apparatus often revolve around the duty of the health care provider to anticipate the harm. Duty can be defined as an obligation to do a thing, a human action exactly conformable to the law that requires us to obey. For the tort of negligence to be a valid claim, the four conditions listed in Box 5-3 must be met.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996

In August 1996, the U.S. Congress enacted HIPAA, which required, among other things, the establishment of Standards for Privacy of Individually Identifiable Health Information. These standards, which have become known as simply the Privacy Rule, added a major dimension to the need to treat medical records and information as confidential. The Privacy Rule was developed, with public comment and input, in the years following the enactment of HIPAA. The final rule was issued in March 2002. Updates to the Privacy Rule are likely to continue, making it imperative that the practitioner remain up-to-date with the latest requirements of the rule. The primary goal of the rule was to strike a balance between protecting individuals’ health information and not impeding the exchange of information needed to provide quality health care and protect the public’s health and well-being.16

The Privacy Rule applies to all health care providers, health plan providers (with some exceptions, such as small employer plans with <50 participants administered solely by the employer), and health care clearinghouses. An example of a health care clearinghouse is an entity that processes insurance claims for payment. Some of the exceptions are complex and are beyond the scope of this chapter. The practitioner in clinical practice need not be concerned with particular exceptions because, in most cases, basic patient confidentially requires a standard at least equal to the strictest interpretation of the Privacy Rule.16

The basic goal of the Privacy Rule is to protect all “individually identifiable health information,” commonly referred to as protected health information (PHI). Protected information includes any record or information that would or could identify or reveal (1) an individual’s past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition; (2) the provision of health care to the individual; or (3) the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to the individual. PHI includes information in any format, which may include patient charts (electronic or paper), faxes, e-mails, or other records. The Privacy Rule provides avenues for the normal and appropriate conduct of health care treatment and business for all “covered entities” and individuals and organizations that have a legitimate need to access and use the information. Consent of the individual is not required for these covered entities.16

Professional Licensure Issues

Licensure Statute

§ 3758.6. Report on Supervisor

1. (a) In addition to the reporting required under Section 3758, an employer shall also report to the board the name, professional licensure type and number, and title of the person supervising the licensee who has been suspended or terminated for cause, as defined in subdivision (b) of Section 3758. If the supervisor is a licensee under this chapter, the board shall investigate whether due care was exercised by that supervisor in accordance with this chapter. If the supervisor is a health professional, licensed by another licensing board under this division, the employer shall report the name of that supervisor and any and all information pertaining to the suspension or termination for cause of the person licensed under this chapter to the appropriate licensing board.

2. (b) The failure of an employer to make a report required by this section is punishable by an administrative fine not to exceed $10,000 per violation.

Respiratory Therapists who Speak Out about Wrongdoing

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

1. Provided, caused to be provided, or is about to provide or cause to be provided to the employer, the Federal Government, or the attorney general of a State information relating to the violation of, or any act or omission the employee reasonably believes to be a violation of, any provision of this title;

2. Actually did or is about to assist, participate, or testify in a proceeding about such violation; or

3. Objected to or refused to participate in any activity or task that the employee “reasonably believed” to be in violation of the statute or any rule or regulation promulgated under the statute.