CHAPTER 6 Esophagectomy

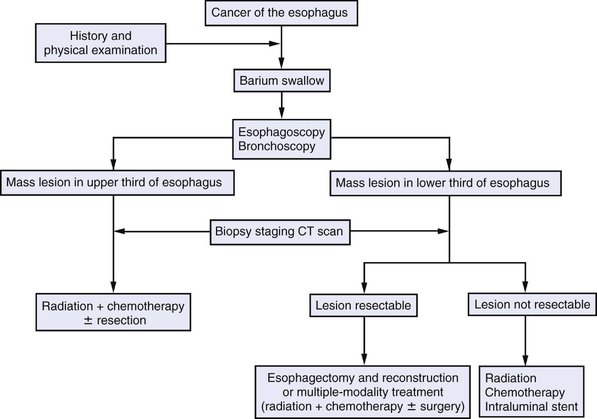

INDICATIONS FOR RESECTION

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

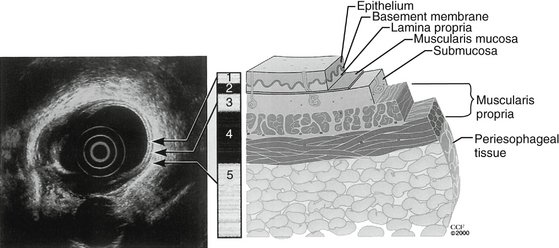

COMPONENTS OF THE PROCEDURE AND APPLIED ANATOMY

Approaches to Esophagectomy

Preoperative Considerations

Exposure and Creation of the Gastric Conduit

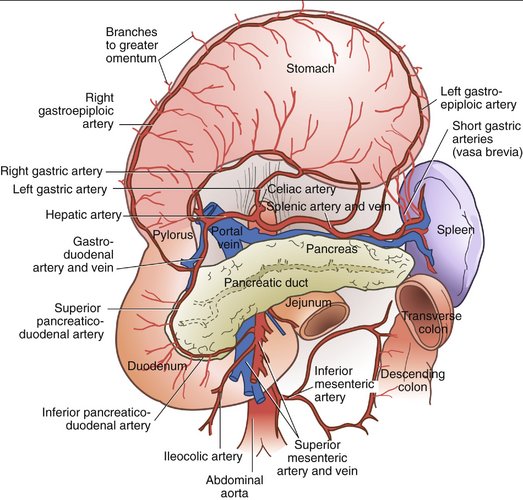

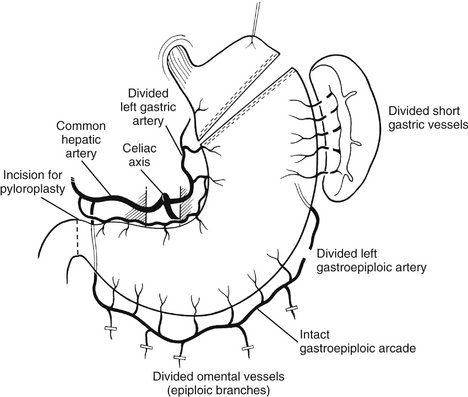

Figure 6-3 Blood supply to the stomach.

(From Zuidema G: Shackelford’s Surgery of the Alimentary Tract, 4th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 1995.)

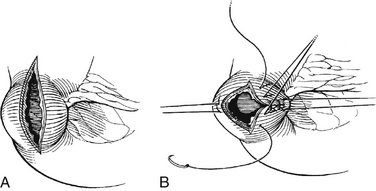

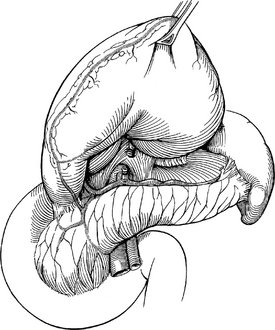

Figure 6-4 Mobilization of the stomach and ligation of the left gastric artery.

(From Cameron JL [ed]: Current Surgical Therapy, 8th ed. Philadelphia, Mosby, 2004.)

Figure 6-5 Preparation of the gastric conduit.

(From Khatri VP, Asensio JA: Operative Surgery Manual. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2003.)

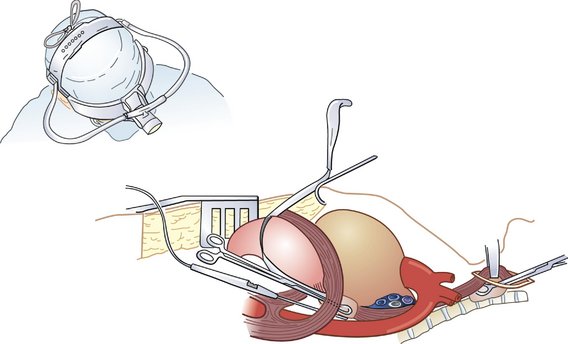

Mobilization of the Esophagus and Anastomosis

COMPLICATIONS

Casson AG. Thoracic approaches to esophagectomy. In: Kaiser LR, Kron IL, Spray TL, et al, editors. Mastery of Cardiothoracic Surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998:141-150.

Cope C, Salem R, Kaiser LR. Management of chylothorax by percutaneous catheterization and embolization of the thoracic duct: prospective trial. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:1248-1254.

Inculet RI. Transhiatal esophagectomy [[eds]]. Kaiser LR, Kron IL, Spray TL, et al, editors. Mastery of Cardiothoracic Surgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 1998, 134-140.

Zwischenberger JB, Savage C, Bhutani MS. Esophagus. In: Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, editors. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 17th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:1091-1150.