Esophageal Foreign Bodies

General Features

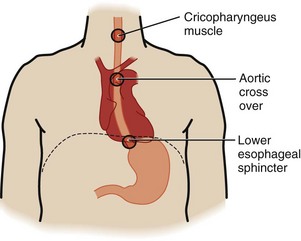

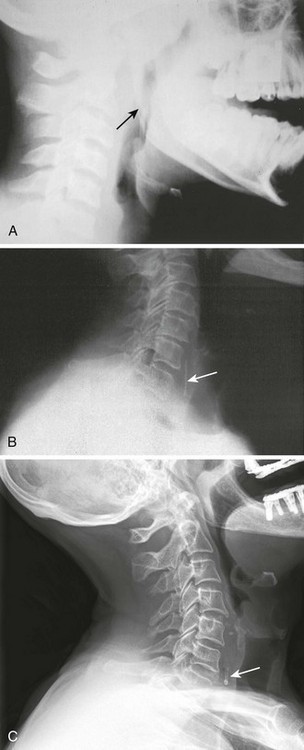

The esophagus is a muscular tube 20 to 25 cm in length. There are three anatomic areas of narrowing in which FBs are most commonly entrapped: in the upper esophageal sphincter, which consists of the cricopharyngeus muscle; in the midesophagus at the crossover of the aortic arch; and in the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) (Fig. 39-1). The LES is the narrowest point of the esophagus and the entire GI tract.

Epidemiology

Children account for 75% to 85% of esophageal FBs seen in the ED, with the peak incidence occurring at the age of 18 to 48 months.1–9 The incidence is equal in boys and girls. Inquisitive children frequently place objects in their mouth and unintentionally swallow them. As a result, children most commonly ingest coins, but they also swallow buttons, marbles, beads, screws, and pins.1,2,4,9–13 Unlike adults, children who have entrapped, accidentally swallowed FBs do not normally have underlying esophageal disorders.14 However, this is not the case in children with esophageal meat impaction, and these patients will need further evaluation for underlying esophageal disease.15

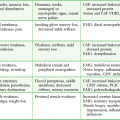

Patients with an anatomic abnormality of the esophagus or a motor disturbance are more prone to FB entrapment.12,15,16 Anatomic abnormalities include strictures, webs, rings, diverticula, and malignancies. Motor disturbances include achalasia, scleroderma, and esophageal spasm. Adults who have dentures or underlying esophageal anatomic or motor abnormalities may accidentally ingest food boluses, chicken bones, fish bones, glass, toothpicks, fruit pits, or pills while in the act of eating.13

Prisoners and psychiatric patients ingest a wide variety of objects, some of which may be quite unusual: spoons, razor blades, pins, nails, or practically any other object.12

Complications

Impacted FBs of the esophagus must be removed or dislodged. The time frame under which this mandate must be carried out varies widely and depends on many circumstances. In general, however, the esophagus does not tolerate FBs well or for prolonged periods because it is prone to pressure, edema, necrosis, infection, and eventually perforation. FBs can transit the esophagus in a matter of seconds or minutes or may adhere to the mucosa. Retained objects may become less symptomatic after time, and the clinician must resist the urge to allow esophageal FBs to “pass by themselves” or “dissolve.” Once FBs become stuck in the mucosa, they may become less symptomatic, but they rarely pass on their own. The one exception may be children with coins, especially those lodged at the LES. Approximately one third of these coins may pass spontaneously within 24 hours, and some authors have advocated an observational approach, although this is more poorly accepted by parents.17–21

A wide array of complications can arise from retained esophageal FBs (Box 39-1), including benign mucosal abrasions, lacerations, esophageal stricture, and necrosis from corrosive agents such as button batteries. Esophageal perforation21–27 can lead to life-threatening conditions such as retropharyngeal abscess,28 mediastinitis, pericarditis, pericardial tamponade,29 pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, tracheoesophageal fistula, and vascular injuries, including injuries to the subclavian vein and aorta.20,30,31 Complications are more common when FBs are entrapped for longer than 24 hours2,32,33 and when they are sharp.34 An estimated 1500 deaths occur annually as a result of esophageal FBs, primarily from complications of esophageal perforation.9

Clinical Findings

Esophageal FB impaction is usually an acute condition, particularly in adults who have a clear history of ingestion. Children also commonly remember an ingestion, but some will have a vague history or symptoms. As many as one third of children with proven esophageal FBs are asymptomatic on initial evaluation20,34–36; therefore, a high index of suspicion is indicated, especially in children who were seen with an object in their mouth that subsequently disappeared. This is particularly true if transient coughing or gagging occurred, even though the actual ingestion was not witnessed. Poor feeding, irritability, fever, stridor, cough, wheezing, and aspiration can all be caused by an underlying esophageal FB in a child, especially a young infant.15,37–39

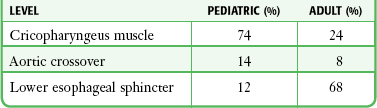

The location of retained esophageal FBs is related to age (Table 39-1). Children more typically have objects entrapped in the upper part of the esophagus at the level of the cricopharyngeus muscle, whereas adults more commonly have entrapment at the LES.18,38,40–42

Evaluation

After attending to life-threatening conditions such as airway compromise, the goal of ED evaluation is to localize the FB to determine what, if any, interventions need to be undertaken to remove it or assist its transit into the stomach. Once an FB passes into the stomach, it has a greater than 90% likelihood of passing through the entire GI tract without any further problems.34 Even large, irregular, and seemingly dangerous FBs will often transit the entire GI tract with relative ease.

Radiology of Esophageal FBs

Indications

Interactive, verbal patients can provide valuable information about the ingested object and can typically localize the retained FB with reliable accuracy.43 In such cases the diagnostic workup should be tailored to localization of the symptoms and ingested material. However, nonverbal patients, including preschool children and those who are demented or debilitated, warrant a low threshold for screening radiography in cases with a suspicious history. Examples include a child seen with an object in the mouth that “disappeared” or a patient with symptomatology suggestive of an esophageal FB, such as drooling, gagging, or unexplained respiratory symptoms.

Plain Radiographs

Unfortunately, many ingested FBs are nonopaque, including nonbony food, plastic, wood, and aluminum. Some pull tabs from beer cans may be seen if oriented in the coronal plane. A metal detector has been reported to help localize radiolucent aluminum pull tabs.44,45 Calcification of fish and chicken bones is often incomplete, but cooking alters the structure of bones and makes them radiolucent on plain films. The degree of bony calcification varies with the fish species and between different samples of the same species, thus preventing useful guidelines.46–49 For these reasons, plain films provide little substantive evidence in the majority of cases of fish or chicken bone dysphagia. They detect only 25% to 55% of endoscopically proven bones and carry a high rate of false-negative and false-positive interpretations.43,48–53 Because of the lack of diagnostic value for detecting bones, many clinicians do not routinely order plain radiographs and instead initially opt for computed tomography (CT) in cases in which radiographic evaluation is required.54,55

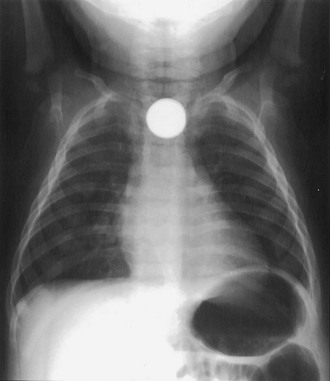

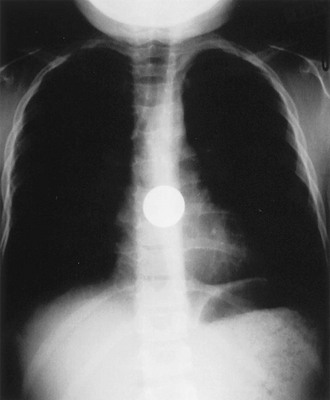

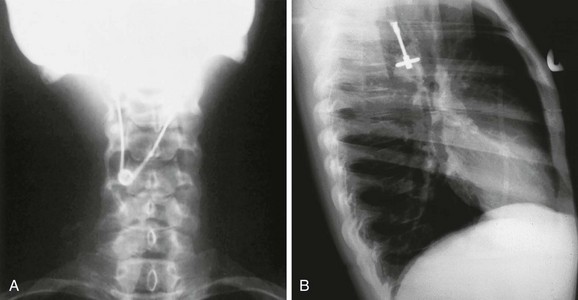

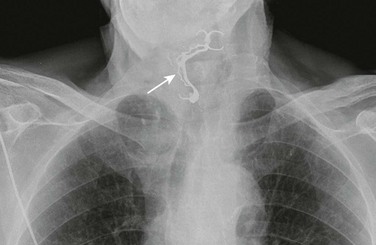

When used, a complete oropharyngeal radiographic series includes the nasopharynx to the lower cervical vertebra in both lateral and anteroposterior views. Optimum-quality radiographs are mandatory. Patients should be positioned upright with the neck extended and the shoulders held low. Use of a soft tissue technique enhances the discrimination of weak radiopaque FBs. Phonation of “eeeee” during radiography prevents motion artifact from swallowing, distends the hypopharynx, and enhances soft tissue landmarks. As previously mentioned, FBs are most frequently entrapped at one of three locations in the esophagus: the cricopharyngeus muscle (Fig. 39-2), the aortic crossover (Fig. 39-3), and the LES (Fig. 39-4).

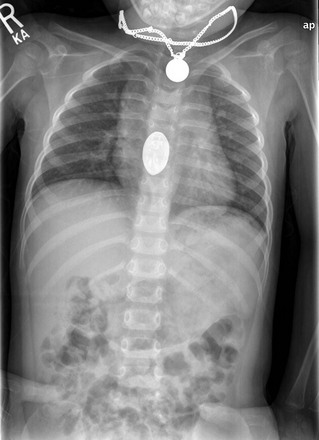

Figure 39-4 Posteroanterior radiograph of an esophageal foreign body (coin) lodged at the level of the lower esophageal sphincter. Coins in this area are most likely to pass and be favorably manipulated by medication (see Table 39-2). Note: The chance of spontaneous passage is about 25% to 60%; chances increase with prolonged observation. (From Waltzman ML, Baskin M, Wypij D, et al. A randomized clinical trial of the management of esophageal coins in children. Pediatrics. 2005;116:614; and Soprano JV, Fleisher GR, Mandl KD. The spontaneous passage of esophageal coins in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1073.)

Plain radiography of the neck is limited by the radiographic properties of ingested materials and the complicated anatomy of the upper aerodigestive tract. The base of the tongue, palatine and lingual tonsils, vallecula, and piriform recesses are common regions for entrapment of small, sharp objects and deserve careful interpretive attention (Fig. 39-5). Superimposition of the mandible contributes to suboptimal resolution of this region on lateral neck films. Calcified airway cartilage often masquerades as FBs and contributes to false-positive rates as high as 25%.43,48,50,52,56–58 Normal ossification of airway cartilage begins in the third decade and progresses with age.59 The typical curvilinear contour and well-defined margins of bony FB fragments may help distinguish them from normal laryngeal calcifications. The orientation of bony FBs is variable. The C6 vertebra approximates the level of the cricopharyngeus, a common site of FB impaction. Increased prevertebral soft tissue width, air within the cervical esophagus, and soft tissue emphysema are rare indirect findings that may help identify radiolucent objects.49,60

Contrast-Enhanced Esophagograms

A contrast-enhanced esophagogram is a test with limited utility in the ED as a routine intervention to evaluate for an esophageal FB. It may be considered when plain radiographs are negative, but esophagography has largely been replaced by CT and endoscopy for evaluation of FBs. This technique uses swallowed contrast material to help identify the presence and location of an impacted radiolucent FB, the degree of obstruction, any underlying anatomic abnormalities, and the presence of perforation. A variation of this technique is to have the patient swallow contrast-soaked cotton pledgets. This technique uses smaller contrast loads and may identify impacted FBs by the impeded progression of the cotton or by tagging sharp irregular objects with radiopaque cotton threads as the bolus passes. Theoretically, this variation might interfere less with follow-up endoscopy because of the attenuated contrast loads. Unfortunately, ingestion of liquid contrast agents yields overall results no better than those of plain film radiography. More importantly, contrast material may interfere with the detection and extraction of FBs at endoscopy (barium) and may increase the risk for aspiration pneumonitis (diatrizoate meglumine and diatrizoate sodium [Gastrografin]).40,61,62 Therefore, routine, serial contrast-enhanced esophagograms after negative plain radiography in patients with known or suspected FBs are unnecessary for diagnostic purposes in most cases. Selective use is reasonable, but CT or endoscopy is the intervention with the best and most cost-effective yield.63

Procedure

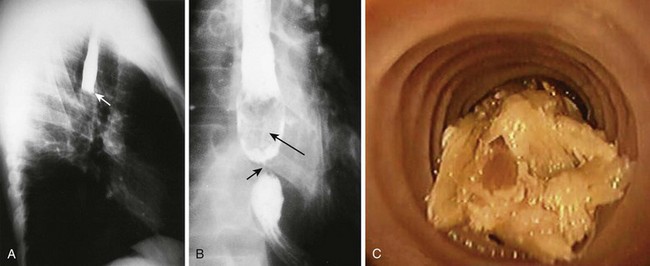

Esophagograms couple voluntary ingestion of an enteric contrast agent (Gastrografin or barium) and plain radiography. Immediately after ingestion, erect and horizontal radiographs are performed at right-angle projections (PA and lateral or right and left anterior oblique). In addition to anatomic abnormalities, radiolucent FBs may be identified by contrast delineation or filling defects within the contrast column (Fig. 39-6).

The initial choice of contrast agent is debated and should be individualized according to the threat of aspiration and perforation. Other logistic concerns, listed later, have relegated this test to minimal use in the ED. Water-soluble Gastrografin is indicated first in most cases of suspected perforation because it causes less mediastinal inflammation when extravasated; however, it can give rise to severe chemical pneumonitis if aspirated and is relatively contraindicated in patients with complete esophageal obstruction.12 Patients without evidence of complete esophageal obstruction are instructed to swallow progressively larger aliquots of contrast agent up to approximately 50 mL. If these films are normal, the procedure is repeated with half-strength and then full-strength barium to delineate small esophageal injuries. Note that water-soluble contrast material (Gastrografin) causes more pulmonary reaction than barium does when inadvertently aspirated and should be used in small aliquots if aspiration or complete esophageal obstruction is a concern. Contrast-enhanced esophagograms coupled with fluoroscopy are seldom used for acute esophageal FB impactions, although slowed progression or abnormal peristalsis may suggest a retained FB or an anatomic abnormality. Barium interferes with endoscopy and should not be used when endoscopy is anticipated.

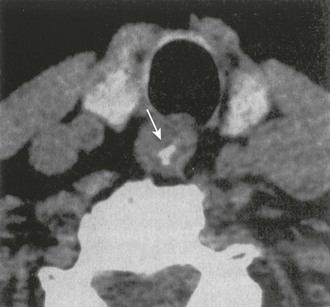

CT

Non–contrast-enhanced CT of the neck and mediastinum is an easy, rapid, cost-effective, and noninvasive means of detecting or ruling out upper GI FBs (Fig. 39-7)48,49,51,54,55 and has garnered support in the clinical setting of suspected FB entrapment.64–66 CT further excels at localization and characterization of the impacted FB and identification of associated complications such as perforation.49,64,67–69

CT clearly provides improved diagnostic utility for fish bone FBs over plain radiography with or without barium enhancement.48,49,51,54 Use of CT in patients in whom clinical suspicion for a retained FB is high has the potential to reduce the number of unnecessary endoscopies.51

Conclusions

Diagnostic radiography for esophageal FBs requires individualization of cases. Plain radiographs clearly assist the clinician in several situations: (1) screening of children, adults with dementia, and nonverbal patients with a history or symptoms suspicious for purposeful or inadvertent FB ingestion that can be assumed to be radiopaque and (2) localization of known radiopaque ingestants to clarify the necessity for and means of FB extraction. Conversely, attempts to verify radiolucent FBs, including bones, by plain radiography are often misleading. Contrast-enhanced esophagograms may be used in special situations but have largely been replaced by CT and direct endoscopy. The use of CT to exclude fish bones and other FBs is effective when initial routine plain films are avoided.63

Visualization of Esophageal and Pharyngeal FBs

Patients with an FB sensation in their oropharynx typified by a “fish bone” or “chicken bone” sensation need to have some form of visualization of their oropharynx performed as part of the physical examination. The three procedures are direct pharyngoscopy, which is simply direct visualization or examination using a tongue blade with a light source that may be a pen light, wall light, or head light; indirect laryngoscopy, which involves using a handheld mirror reflecting a light to allow visualization of the epiglottis, vallecula, arytenoids, arytenoids folds, and vocal cords—a procedure that requires experience and a cooperative patient; or nasopharyngoscopy, a procedure using a flexible nasopharyngoscope. If an FB is visualized (Fig. 39-8), it should be removed with forceps and the oropharynx carefully reexamined for any injury or additional FB. All three of these procedures are discussed in detail in Chapter 63.

Esophagoscopy

Esophagoscopy is the definitive diagnostic and therapeutic procedure for impacted esophageal FBs.9,41 Although esophagoscopy is not a procedure performed by the emergency clinician, its proper role in the ED evaluation of FBs must be understood. With esophagoscopy, the clinician can document the presence and location of the FB along with any underlying lesion. The clinician can then remove the object and reevaluate the esophagus after removal of the FB to rule out perforation or underlying pathology. Esophagoscopy may be necessary even if a radiologic contrast-enhanced study does not reveal complete obstruction because x-ray studies are not always conclusive.8,70 Esophagoscopy may be necessary to exclude predisposing pathology or resultant perforation, even when symptoms presumed to be due to an esophageal FB have resolved.

Esophagoscopy is the preferred method for removal of sharp or pointed objects such as bones, open safety pins, and razors. In the case of sharp objects prone to causing esophageal perforation, intravenous antibiotics should be administered before the procedure. Endoscopy is the preferred way to remove an impacted meat bolus and to evaluate for possible esophageal pathology at the same time. Esophagoscopy is also indicated for an FB retained for more than 24 to 48 hours, both to remove it and to examine for esophageal wall erosion or perforation. Esophagoscopy is the only appropriate removal technique for multiple or large esophageal FBs. This technique is also indicated for patients with an FB proved to have passed into the stomach and for those who have persistent symptoms possibly caused by esophageal wall injury. Flexible endoscopic procedures can usually be performed without general anesthesia, even in most children.71 The success rate of flexible endoscopy in patients with retained esophageal FBs exceeds 96%.41,72

Traditionally, esophagoscopy is more expensive than other maneuvers such as Foley catheter removal or esophageal bougienage (described later),3,7,73,74 largely because of charges for the surgical suite, but it has a higher success rate than the other two techniques do. ED removal of esophageal FBs in children by experienced endoscopists, while the child is under ketamine sedation administered by the emergency clinician, has been reviewed.75 In selected cases this approach can shorten the interval to completion of the procedure and reduce expense.

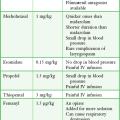

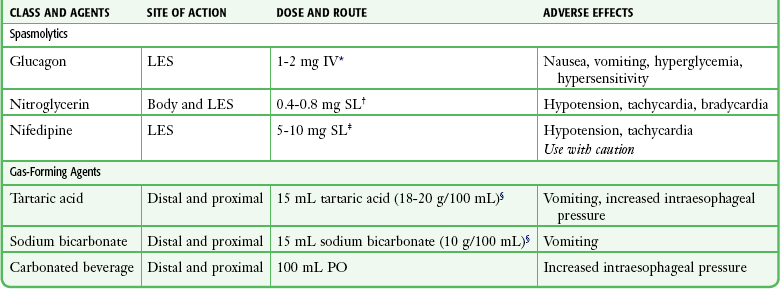

Esophageal Pharmacologic Maneuvers

Several pharmacologic agents, including diazepam, meperidine, and atropine, have been shown to be unsuccessful in removing or resolving esophageal impaction by FBs.13 These agents, alone or in combination, have success rates below 10%, which is no better than observation alone.2 Glucagon, nitroglycerin, nifedipine, and gas-forming agents (Table 39-2) are described later and are the most effective pharmacologic agents for treatment of distal esophageal food impaction.

TABLE 39-2

Recommended Pharmacologic Therapies for Esophageal FBs

*May be repeated once or used in conjunction with nitroglycerin.

†One to 2 inches of nitroglycerin paste applied under an occlusive dressing may be an alternative.

‡A capsule is punctured, chewed, held in the mouth for 3 minutes, and then swallowed. Because of hypotension, a 5-mg dose may be used in the elderly. Do not use if the patient has cardiovascular disease, is hypotensive, or has also recently been given nitroglycerin.

§Alternatively, dissolve 2 to 3 g tartaric acid and 2 to 3 g sodium bicarbonate in 30 mL water.

Glucagon

Glucagon has been a prototype for the spasmolytic agents.76–78 Glucagon theoretically relaxes esophageal smooth muscle and decreases LES resting pressure. One study of normal subjects found that glucagon significantly lowers mean LES resting pressure but causes no significant difference in the mean amplitude of contraction in the distal end of the esophagus.79 Glucagon has no effect on the upper third of the esophagus, a common site of coin impaction in children, where striated muscle is present and some voluntary control is operative. It only minimally affects the middle third of the esophagus. Peristalsis is not affected by glucagon. Results with glucagon have been mixed, and the only randomized study, done in children, showed no better results than those achieved with placebo.80 A nonrandomized study in adults showed that glucagon is about equivalent to placebo, with a 33% success rate, and that the addition of a benzodiazepine increases the success rate slightly.81 Its use, however, is still advocated by some authorities and has little downside. Glucagon may cause vomiting, and this action may be responsible for some of the drug’s success.82

Indications and Contraindications

Glucagon is most useful for smooth FBs or food impactions at the LES that are suspected because of a patient’s complaint of pain or “something stuck” in the lower part of the chest or epigastrium. The clinical diagnosis is usually straightforward, especially if complete esophageal obstruction is present and the patient is unable to tolerate oral secretions. Nevertheless, some clinicians recommend that the FB be localized first with radiographs (with or without contrast enhancement) to establish that the impaction is indeed there. The radiographs can then serve as the baseline study for comparison after administration of glucagon. However, with classic findings on the history and physical examination, most investigators agree that an initial contrast-enhanced study can be omitted. Glucagon is not effective in relieving upper and middle esophageal obstruction, and it is not widely recommended for use in children. In addition, glucagon is not usually effective in patients with fixed fibrotic strictures or rings at the gastroesophageal junction.77 Glucagon is contraindicated if the patient has an insulinoma, pheochromocytoma, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, hypersensitivity to glucagon, or a sharp esophageal FB.

Administration of Glucagon

Some reports recommend a small test dose to check for hypersensitivity to glucagon. In practice, this is rarely done. The therapeutic dose is 0.25 to 2 mg administered intravenously over a period of 1 to 2 minutes in a seated patient, although one study found that in normal subjects, 1 mg of glucagon provides no significant additive benefit over 0.5 mg.79 The patient is given water orally within 1 minute after the injection of glucagon to stimulate normal esophageal peristalsis; this helps push the food through the relaxed LES into the stomach. Glucagon has a rapid onset and short duration of action: GI smooth muscle relaxes within 45 seconds, and its duration of action is about 25 minutes. If no results are seen within 10 to 20 minutes, a second administration of 0.25 to 2 mg may be tried. Success rates are higher when glucagon is combined with gas-forming agents or even carbonated beverages.83,84 It is recommended that a small volume of some oral fluid be routinely given to enhance the activity of glucagon.

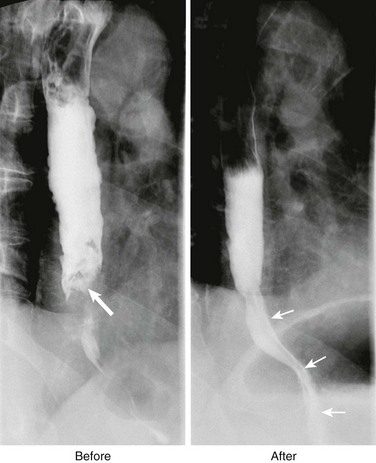

Further Evaluation and Therapy

If the patient experiences relief of symptoms after the administration of glucagon, a postprocedure radiograph or contrast-enhanced study may be obtained to confirm passage of a radiopaque object, but this is not mandatory (Fig. 39-9). Adult patients with successful FB passage into the stomach may also be discharged home, but careful follow-up should be obtained to rule out coexistent esophageal pathology because a significant number of patients (65% to 80%) will have underlying esophageal disorders.9,16 Pediatric patients with food boluses lodged in the esophagus also have a high rate of underlying esophageal disease and need referral for further evaluation; this is not the case for accidentally swallowed FBs in children.15 If glucagon fails to produce relief of the symptoms or resolve the radiograph findings, its use does not preclude other methods from being used.

Nitroglycerin and Nifedipine Pharmacology

Both sublingual nitroglycerin and nifedipine have been used in a manner similar to glucagon to relieve LES tone and allow the passage of a distal esophageal FB.85–87 Although these two agents have been used less than glucagon for the treatment of esophageal FBs, both are useful for the relief of chest pain associated with esophageal smooth muscle spasm64 and may be administered concurrently with glucagon. Manometric and radiographic studies after the administration of nitroglycerin have revealed abolition of the repetitive high-pressure wave contractions characteristic of esophageal spasm. Nifedipine, conversely, significantly reduces LES pressure without changing contraction amplitudes in the body of the esophagus. Thus, nitroglycerin may relieve partial or complete obstruction of the middle or lower part of the esophagus secondary either to intrinsic esophageal disease or to simple FB impaction, and nifedipine, like glucagon, is most likely to succeed when the bolus is lodged at the gastroesophageal junction.

Indications and Contraindications

Similar to clinical indications for the use of glucagon, any patient with an impacted smooth esophageal FB, especially a food bolus, may be a candidate for nitroglycerin or nifedipine (or both). Also, similar to the mode of action of glucagon, neither of these agents is expected to relax a fixed fibrotic stricture or ring at the gastroesophageal junction.77 Nevertheless, because both agents have a relatively benign side effect profile, if the patient has no contraindication to their use, they may be tried with or without previous documentation of the distal esophageal obstruction with a contrast-enhanced study. Contraindications to their use include a history of allergic reactions, a sharp esophageal FB, hypovolemia, and hypotension.

Use and Complications

Doses of 1 or 2 (0.4 mg) sublingual nitroglycerin tablets, 1 to 2 inches of nitroglycerin paste, or 5 to 10 mg of nifedipine have been reported.85–87 Remember that some patients with esophageal FBs may have some degree of dehydration because of the inability to swallow liquids or their own saliva. These patients may be prone to hypotension from the vasodilation associated with the use of either agent. Ideally, rehydration should precede therapy with these agents. Sublingual nifedipine (5- to 10-mg capsule punctured, chewed, and swallowed) has been implicated in cerebral or coronary insufficiency in patients with cardiovascular disease, so caution is warranted. Do not use both agents simultaneously. The smaller dose of nifedipine is suggested in the elderly or those with cardiovascular disease.

Gas-Forming Agents

The use of gas-forming agents for the treatment of distal esophageal food impaction, especially meat boluses, was first described in 1983.88 The combination of tartaric acid solution followed immediately by a solution of sodium bicarbonate or even carbonated beverages has been reported. In theory, use of this acid-base mixture or a carbonated beverage may produce sufficient carbon dioxide to distend the esophagus, relax the LES, and push impacted food through the gastroesophageal junction into the stomach.89,90

Indications and Contraindications

Gas-forming agents are indicated for the relief of smooth distal esophageal FB impaction, with or without prior FB confirmation by a radiographic study (see Fig. 39-9). They are often given to patients with food impaction or retained coins. Although gas-forming agents are more likely to succeed with distal esophageal impactions, they have also been successful in relieving obstructions in the proximal part of the esophagus. Concurrent administration of spasmolytic agents may improve the effectiveness of gas-forming agents.84

Use and Complications

A solution of 15 mL of tartaric acid (18.7 g/100 mL), followed by 15 mL of a sodium bicarbonate solution (10 g/100 mL), or 1.5 to 3 g of tartaric acid and 2 to 3 g of sodium bicarbonate dissolved in 15 mL of water can be used.88,89 Carbonated beverages (100 mL) have also been successful in the transit of FBs into the stomach89,90 and are more readily available in the ED. Many patients with esophageal FB impaction have been noted to retch after receiving gas-forming agents, which theoretically puts patients at risk for esophageal trauma, including rupture. Gas-forming agents should not be given to patients with impactions of greater than 6 hours’ duration or to patients with chest pain that might be indicative of an esophageal injury.

Papain

Papain is not recommended for treatment of an esophageal FB. It is a proteolytic enzyme that has been touted for its ability to dissolve meat impactions.91 Papain is available commercially in a variety of meat tenderizers. This therapy has never been tested in a clinical trial. Although it is harmless when in brief contact with a normal esophagus, if it is left in an obstructed esophagus too long, papain may begin to dissolve the esophageal mucosa underlying an FB. This is likely to occur when the esophageal wall is ischemic secondary to FB impaction and the resultant wall pressure, when esophageal injury results from small bony spicules in the FB, or when an underlying lesion is responsible for the obstruction. The subsequent rupture and leakage of proteolytic enzymes result in a self-perpetuating mediastinitis. Patients with esophageal FBs are at increased risk for aspiration, and pulmonary aspiration of papain results in acute hemorrhagic pulmonary edema. Papain is not currently recommended because of the unacceptable risk for complications and the availability of safer, more effective interventions.

Removal of Esophageal FBs in the ED

In the United States the most prevalent method for removing FBs lodged in the esophagus is referral for removal under direct visualization via endoscopy, normally done in either an endoscopy suite or operating room under sedation. Endoscopy is costly7,74,92,93 and time-consuming, and if the patient is being seen after hours, the procedure requires additional personnel to come into the hospital to care for the patient. With procedural sedation becoming more common in EDs, procedures to remove lodged esophageal FBs, when appropriate, are becoming more common. Currently, three procedures are used in the ED to remove FBs lodged in the esophagus, and these are somewhat dependent on the type and location of the FB. These procedures include Magill forceps removal, Foley catheter removal, and esophageal bougienage. Each will be described separately. Another strategy, “watchful waiting,” is reserved for single, smooth, asymptomatic FBs typically at the LES in children and will also be discussed.

Magill Forceps Removal of Esophageal FBs

In children, the most common accidentally ingested FB is a coin, and the most common location for the FB to be lodged is at the cricopharyngeus muscle (Fig. 39-10). Given these facts, when children have a single coin at the level of the cricopharyngeus muscle confirmed by radiographs, they are candidates for Magill forceps removal. The procedure requires sedation (see Chapter 33), and thus all airway equipment must be available, as well as monitoring equipment and expertise in its use. In centers that are using this procedure, success rates have ranged from 95% to 100%.94–97 All centers reporting this procedure used sedation and visualization with a laryngoscope or video-assisted system. The procedure was rapidly performed, usually in less than a minute.94,97 Complications were rare and typically consisted of minor bleeding or vomiting. In the one center that intubated patients before the procedure, complications were higher and associated with the intubation.96 Magill forceps removal seems to be ideally indicated for stable children with a coin at the cricopharyngeus muscle in a facility that is well equipped and staffed and experienced in managing procedural sedation and airways in children.

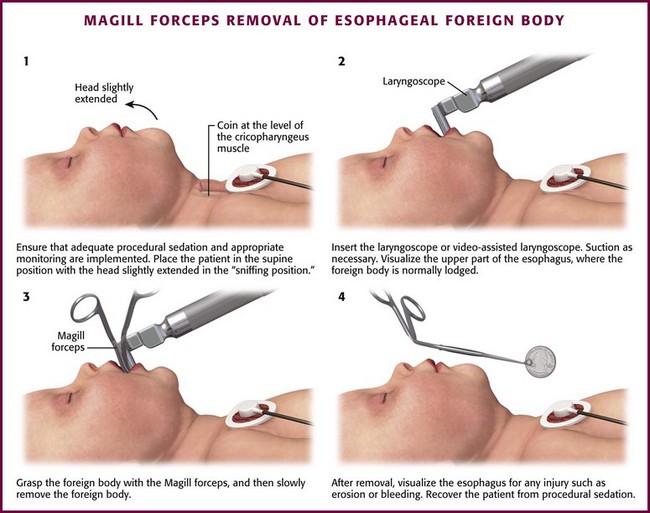

Procedure (Fig. 39-11)

1. Ensure that adequate procedural sedation and appropriate monitoring are both implemented (refer to Chapter 33). Place the patient supine on the stretcher with the head slightly extended in the “sniffing position.”

2. Insert the laryngoscope or video-assisted laryngoscope. Suction as necessary.

3. Visualize the upper part of the esophagus, where the FB is normally lodged.

4. Grasp the FB with the Magill forceps and then slowly remove it.

5. Visualize the esophagus after removal for any injuries such as erosion or bleeding.

Aftercare

No specific aftercare is necessary if no complications have occurred from the procedure. If there is any evidence of esophageal injury, the patient needs to be referred to gastroenterology immediately. Children who ingest FBs are at risk for future ingestions, with the “repeat offender” rate being as high as 18% to 20%.34

Foley Catheter Removal of Esophageal FBs

Foley catheter removal of esophageal FBs was first described in the thoracic surgery literature in 196698 and in the emergency medicine literature in 1981.99 The technique has essentially been unchanged since the first reports and is now used by emergency clinicians, radiologists, otolaryngologists, and general surgeons.100–103 The classic patient for this technique is a small child who is brought to the hospital shortly after swallowing a coin that is documented by radiography, but the procedure may be used for a wide variety of smooth FBs in patients of all ages. Success rates for Foley catheter removal of FBs have been cited from 85% to 100%, with complication rates of 0% to 2%.7,72,104–108 Many of the reported complications were due to nasal insertion of the catheter, and complication rates are lower when the catheter is inserted orally and at centers that perform the procedure frequently. Foley catheter extraction of FBs costs significantly less than endoscopy.7,92,109 Fluoroscopic assistance may be preferable, but it is not essential. Whether the procedure is performed in the ED or the radiology department, equipment and personnel capable of emergency pediatric airway management must be present.

Indications

Recently ingested smooth, blunt objects that are radiographically opaque are most suitable for balloon catheter extraction. Recently ingested FBs carry little likelihood of causing pressure necrosis, perforation, or other significant injury; however, 24 to 48 hours’ duration of impaction should be the upper limit for consideration of this technique.7,33,92

Coins are particularly amenable to Foley manipulation, but food boluses and button batteries have also been extracted successfully.99 Radiographically opaque objects are most easily located with plain radiographs. Radiolucent objects can be manipulated, but uncertainty about location mandates contrast-enhanced esophagography.

Procedure (Fig. 39-12)

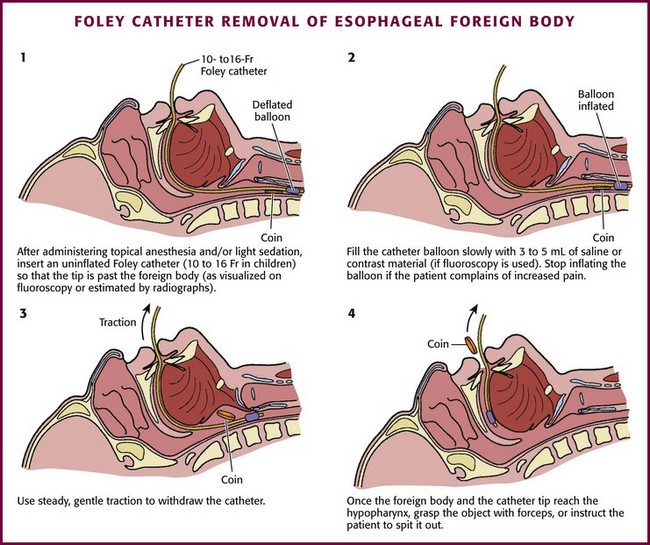

1. Coach the patient on the procedure. Topical oropharyngeal anesthesia may be used (although this increases the risk for aspiration). Light sedation may be used.

2. Place the patient in the Trendelenburg, lateral decubitus, or prone position.

3. Insert an uninflated catheter (10 to 16 Fr in children) so that the tip is past the FB (as visualized on fluoroscopy or as estimated on radiographs).

4. Fill the catheter balloon slowly with 3 to 5 mL of saline or contrast material (if fluoroscopy is used). Stop inflating the balloon if the patient complains of increased pain.

5. Use steady, gentle traction to withdraw the catheter.

6. Once the FB and the tip of the catheter reach the hypopharynx, grasp the object with forceps, or instruct the patient to spit it out.

7. Obtain another radiograph to ensure that multiple FBs were not present.

8. If the catheter slips by the FB, reinsert the catheter, inflate it with an additional 2 to 3 mL of fluid, and make one additional attempt at withdrawal.

9. If fluoroscopy is not used and no FB is retrieved, another radiograph should be obtained because 10% to 20% of the time the FB will pass distally into the stomach.

Complications

Complication rates of 0% to 2% have been reported.7,72,104–108 Many complications (nosebleeds or displacement of the FB into the nose) have been related to nasal insertion of the catheter. Complication rates are lower when the catheter is inserted orally and generally lower at centers that perform the procedure frequently. No deaths have been reported. Laryngospasm and aspiration are rare complications. Failure to either remove the object or displace it into the stomach occurs in approximately 2% to 10% of carefully selected patients,104,106–109 but success rates are lower in adults or patients with underlying esophageal disorders.108

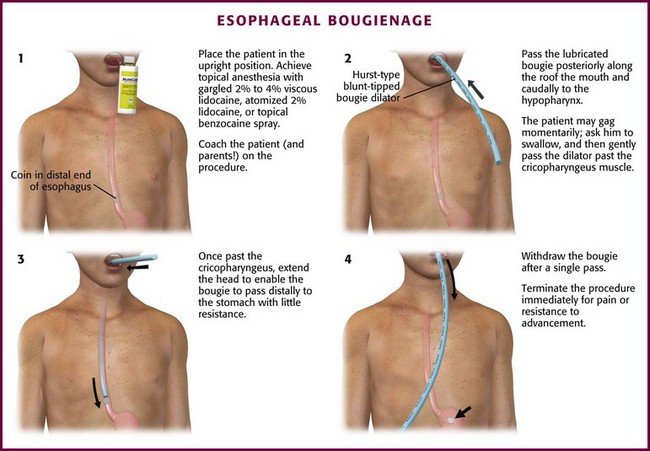

Esophageal Bougienage

Displacement of esophageal FBs into the stomach can be done with nasogastric or orogastric tubes or via esophageal bougienage. Esophageal bougienage is a technique for dislodging impacted esophageal coins by blind mechanical advancement of the coin into the stomach, a procedure first described in 1965.110 The technique has greater than a 95% success rate with essentially no reported complications when used for the proper indications.7,73,74,111,112 Rates as high as those with endoscopy have been reported.92 Furthermore, bougienage is unrivaled in overall cost-effectiveness since it is approximately 10% of the cost of endoscopic removal.7,74,92,113

This technique does not allow visualization of the esophagus or retrieval of the object. There have traditionally been warnings against forceful advancement of esophageal FBs, but growing evidence verifies the efficacy and safety of blind esophageal bougienage as first-line therapy for coin ingestions in properly selected patients. Although early articles suggested that esophageal bougienage should be performed exclusively by pediatric surgeons, the technique is easily mastered and used by emergency clinicians.74,112

Indications and Contraindications

Strict patient selection is paramount for successful and uncomplicated bougienage. The criteria have changed little since initially proposed and define a group in whom a round, smooth object can be forcibly passed into the stomach with little risk.93,111 Although many swallowed objects meet this description, only coins hold clear supportive evidence in the literature. Since many patients with impacted food or meat have underlying esophageal pathology, we do not suggest that it be used in the ED for this condition. Selection criteria are the following: a single, smooth FB lodged less than 24 hours in a patient with no respiratory distress or history of esophageal disease, including previous FBs or surgery. The FB should be likely to pass beyond the stomach without complications. The procedure is contraindicated in patients who do not satisfy all the criteria. It is important to ascertain the duration of esophageal impaction to avoid performing the procedure when there may be underlying esophageal injury. For this reason, some advocate the requirement that the ingestion be clearly witnessed less than 24 hours before arrival at the ED.113 Plain radiographs are indicated to verify coin location and the absence of multiple esophageal bodies. Preprocedure esophagograms are not required.

Procedure (Fig. 39-13)

Figure 39-13 Esophageal bougienage.

1. Coach the patient (and parents) on the procedure. Place the patient in an upright position.

2. Achieve topical anesthesia with gargled 2% to 4% viscous lidocaine, atomized 2% lidocaine, or topical benzocaine spray.

3. Flex the patient’s head, open the mouth, and ask the patient to protrude the tongue. Use a tongue blade if necessary.

4. Pass a well-lubricated, appropriately sized bougie posteriorly along the roof of the mouth and caudally to the hypopharynx.

5. The patient may gag momentarily—ask the patient to swallow and gently pass the dilator past the cricopharyngeus muscle.

6. Ask the patient to phonate while passing the bougie at this point.

7. Once past the cricopharyngeus, extend the head to enable the bougie to pass distally to the stomach with little resistance.

8. Withdraw the bougie after a single pass.

9. Terminate the procedure immediately if pain or resistance to advancement is encountered.

Aftercare

Plain radiographs of the chest and abdomen are indicated to verify passage of the FB into the stomach and to check for any potential complications. Discharge asymptomatic patients with appropriate precautions, including the need to return if signs of respiratory compromise, chest or abdominal pain, dysphagia, hematemesis, persistent vomiting, or other concerns are present. Follow-up abdominal radiographs may be performed to document passage of the coin if it is not identified in feces within 1 week. For adult patients, follow-up is mandated because of the 65% to 80% chance of underlying esophageal disorders.9

Special Situations

Coins are among the most commonly ingested objects by preschool-age children. In most cases, the ingestion is quickly realized by a caretaker, and in the majority of cases the coins pass uneventfully.114 Rarely, an esophageal coin can be clandestine for many weeks or months and produce a variety of vague respiratory or GI symptoms.115 In addition, many coin ingestions are not witnessed,39 so maintain a high index of suspicion for children with dysphagia, drooling, or crying, who may have esophageal FBs, most likely coins.

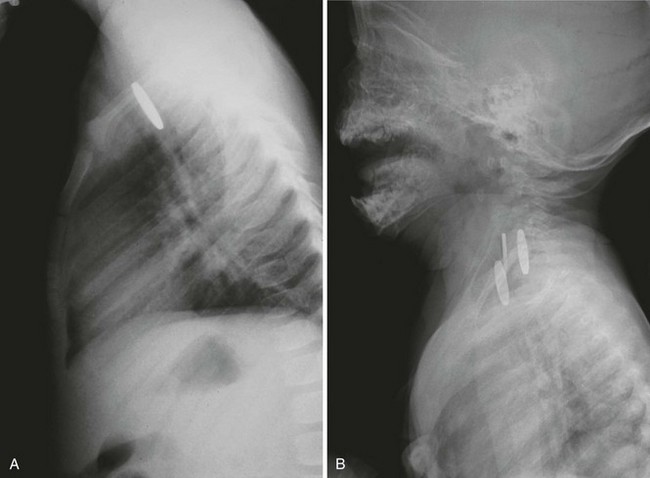

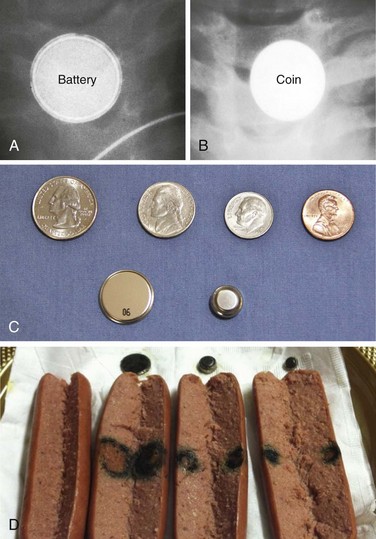

The first clinical decision is whether to obtain a radiograph. Although some authors recommend that asymptomatic children not be radiographed, it is important to remember that up to 44% of children with esophageal coins may be asymptomatic. Therefore, it is prudent to obtain plain radiographs in all children with a suggestive history.35 In most cases a single film that includes the pharynx, esophagus, and stomach will suffice to prove or exclude an ingested coin (Fig. 39-14). Another advantage of obtaining radiographs is to rule out multiple FB ingestions, which are not uncommon in children.116 Only a single PA chest film is needed to prove the presence of a coin, but a lateral projection is also suggested. If the flat surface of the coin is seen (see Figs. 39-2 to 39-4), this orientation ensures an esophageal position. If the edge of the coin is seen, this orientation suggests that it has traversed the vocal cords, but a coin in the airway is not subtle and produces obvious distress. It is advisable to also routinely obtain a lateral radiograph to determine whether multiple coins are stacked on top of each other (Fig. 39-15).

Once a coin’s presence has been documented, a decision concerning removal must be made. The approach varies, and there is no agreed standard. Overall, about 25% of coins will pass spontaneously, even if the coin is located proximally. Observation for 8 to 16 hours is a reasonable approach for asymptomatic children if the ingestion has taken place within 24 hours. Coins in the upper and middle third of the esophagus are less likely to pass spontaneously, and some prefer to remove them as soon as the diagnosis is made.18 Coins in the distal end of the esophagus will pass spontaneously in one third to one half of patients within 24 hours.18,35,117

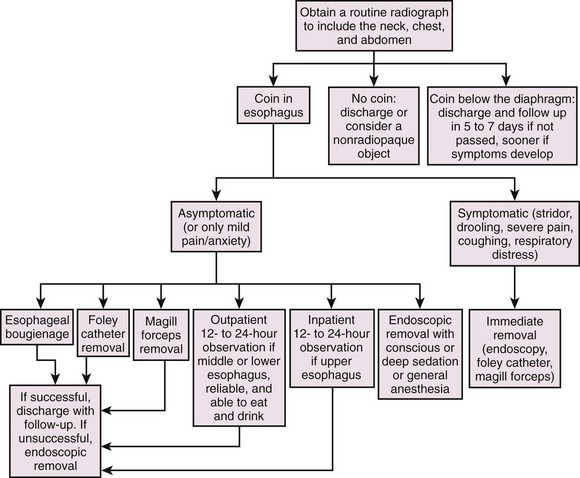

One suggested protocol (Fig. 39-16) involves radiologically localizing the coin and, if the child is symptomatic, immediately removing the coin. If the patient is asymptomatic, the coin may be removed immediately or the patient may be observed either as an inpatient or at home. If the child is asymptomatic, one common practice is to allow the child to drink a carbonated beverage and eat a small amount of soft food in the ED, wait about 1 to 2 hours, and obtain another radiograph. If sent home with an asymptomatic retained FB, the patient is allowed to eat or drink but should be rechecked in 12 to 24 hours with the knowledge that up to 50% of asymptomatic coin FBs will pass into the stomach spontaneously.18,35,118

Finally, there are theoretical concerns about U.S. pennies, which contain 97.5% zinc. Theoretically, zinc can lead to mucosal ulceration from the caustic nature of zinc119; however, the evidence to date suggests no increased risk from ingested pennies.120

Fish or Chicken Bones in the Throat

If the patient feels pain in the upper part of the throat, special attention is directed to the tonsils because bones often lodge in this area (Fig. 39-17). Strands of saliva may mimic a bone, and small bones may be difficult to see. More commonly, the area of complaint is below the oropharynx. In these patients, indirect laryngoscopy or nasopharyngoscopy should be the first step, once again removing the bone if one is seen. This can also be accomplished with local oropharyngeal anesthesia by topical spray and direct visualization with a laryngoscope blade or commercial videoscope blade and then removal of any bone with forceps.

Most patients with an oropharyngeal FB will not have an easily identified or visualized object on examination. These patients present a diagnostic dilemma for several reasons. Only 17% to 25% of patients complaining of an FB sensation after eating chicken or fish have an endoscopically proven bone present, and only 29% to 50% of endoscopically proven bones are seen on plain films.64,121,122 The symptoms in patients with an FB sensation but no FB on endoscopy are believed to be due to esophageal abrasions.

For these reasons, a two-tiered, but individualized approach to managing these patients is proposed.6,9,34 The patient receives a physical examination and the bone is removed if seen. Carefully examine the tonsils, posterior pharynx, and base of the tongue, which are common places for bones to lodge. If the bone is removed and the symptoms disappear, no further intervention is required and follow-up is instituted as needed. Removal of a bone usually provides immediate and complete relief of symptoms. Persistent symptoms are cause for further evaluation based on individual circumstances.

Sharp Objects in the Esophagus

Sharp objects cause the majority of complications seen in patients with esophageal FBs. Such objects include tacks, pins, open paper clips, bobby pins, toothpicks, and razor blades (Fig. 39-18). They will not usually pass spontaneously and should be removed. The only appropriate removal technique is under direct visualization with endoscopy. Swallowed dentures or partial plates are a particular hazard in elderly, demented, or mentally challenged patients. Frequently, there is no history of such, and patients have a variety of complaints, such as a sore throat or persistent vomiting (Fig. 39-19). Prisoners and psychotic patients are well known to clandestinely swallow multiple bizarre and sharp objects.

Attempts at radiographic localization are appropriate for metallic or radiopaque FBs. Most objects in the stomach, even those considered problematic, will transit the remainder of the GI tract if less than 6 cm in length or 2 cm in diameter. If larger than this, consult a gastroenterologist. If radiographs show the FB in the esophagus, endoscopic removal is indicated, and attempts to remove such objects in the ED by other methods are not indicated. Complication rates for endoscopic removal of sharp FBs range from 0% to 3%.8,40

Impacted Food Bolus

A large bolus of food may become impacted in the esophagus, usually at the LES. This occurs most frequently in the elderly, those intoxicated while eating, or those with dentures. Frequently, underlying esophageal pathology is present, such as a stricture or web, even in the young (see Fig. 39-6). The diagnosis is usually straightforward, and patients may be in significant distress, gagging, and unable to swallow. A barium swallow may be used to confirm the diagnosis, but this is rarely necessary. Proceeding directly to endoscopy appears most reasonable. Food boluses may be amenable to pharmacologic relaxation of the LES, but the definitive intervention is endoscopy to both remove the bolus and evaluate the esophagus for pathology. The specific approach, however, is varied and not standard.

Button Battery Ingestion

Button batteries lodged in the esophagus should be considered an emergency because of the potential for serious morbidity and mortality.22,24,123,124 These batteries range in size from 7 to 25 mm and are radiopaque (Fig. 39-20). Batteries appear as round densities, similar to an impacted coin, but some demonstrate a “double-contour” configuration. It is important to distinguish between a coin and a button battery because button batteries require immediate removal. Batteries consist of two metal plates joined by a plastic seal. Internally, they contain an electrolyte solution (usually concentrated sodium or potassium hydroxide) and a heavy metal such as mercuric oxide, silver oxide, zinc, or lithium.

If ingested, these batteries often lodge in the esophagus. Mechanisms of injury include electrolyte leakage, injury from electrical current, heavy metal toxicity, and pressure necrosis. Of particular concern is the development of corrosive esophagitis or perforation as a result of caustic injury and prolonged mucosal pressure. Though essentially harmless in the stomach and intestines, batteries lodged in the esophagus should be considered an emergency situation because even new batteries are subject to corrosion and leakage, which can result in mucosal necrosis within a few hours of contact with the esophagus.23,24,123,124

Once in the stomach, button batteries do not require removal. They may be monitored radiographically to demonstrate passage, with little risk for GI injury or heavy metal poisoning, even if the battery opens.125–128

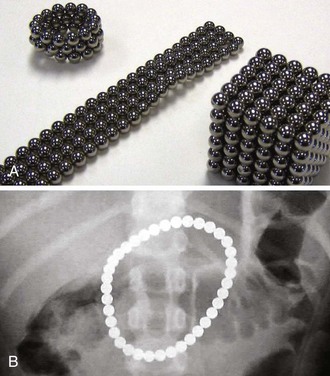

Magnets

Swallowed small magnets from toys and household items have become a serious health hazard in children. Some children with complications from multiple magnet ingestion have underlying conditions such as developmental delay or autism, but older children can inadvertently swallow magnets when using them to imitate a pierced tongue. In 2011 the U.S. Consumer Safety Product Commission issued an alert describing the safety risks from swallowed magnets (http://www.cpsc.gov/cpscpub/prerel/prhtml12/12037.html). Buckyball magnets are small round strong magnets used to make toys of various shapes, and if multiple balls are swallowed, they will become adherent inside the bowel (Fig. 39-21). Multiple magnets, especially if ingested at different times, may attract each other across layers of bowel and lead to pressure necrosis, fistula, volvulus, perforation, infection, or obstruction. A piece of bowel may be pinched by two magnets that are swallowed simultaneously. Hence, suspected magnet ingestion requires urgent evaluation. Radiographs of the neck and abdomen should be obtained to prove magnet ingestion, but radiographs cannot determine whether bowel wall is compressed between the magnets. Identification of magnets that appear to be stacked but slightly separated raises concern for bowel entrapment.

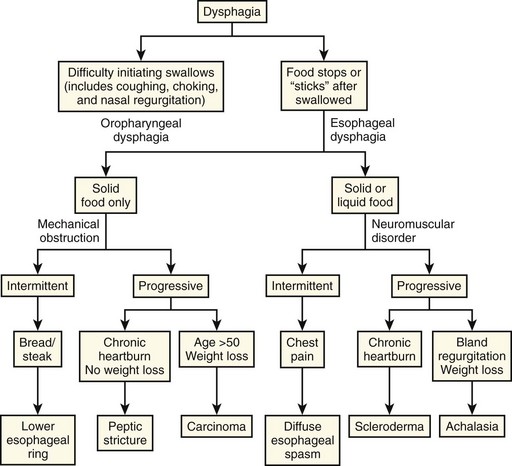

ED Evaluation of FB Sensation in the Throat

FB impactions in the esophagus are usually straightforward, but patients may seek treatment in the ED because of a lump in the throat or difficulty swallowing with no apparent reason or history of FB ingestion. Such complaints require an examination and an investigation based on the clinical encounter and individual circumstances. Complete evaluation of these complaints is beyond the scope of this chapter, but initial modalities available to the clinician to evaluate these complaints are barium swallow, CT, and pharyngoscopy or laryngoscopy. The need for consultation is based on the clinical scenario. Figure 39-22 is a suggested approach to patients with dysphagia without an FB found on evaluation.

References

1. Chinski, A, Foltran, F, Gregori, D, et al. Foreign bodies in the oesophagus: the experience of the Buenos Aires paediatric ORL clinic. Int J Pediatr. 2010. [2010. pii:490691].

2. Chaikhouni, A, Kratz, J, Crawford, F. Foreign bodies of the esophagus. Am Surg. 1985;51:173.

3. Conners, GP, Chamberlain, JM, Ochsenschlager, DW. Conservative management of pediatric distal esophageal coins. J Emerg Med. 1996;14:723.

4. Garcia, C, Frey, CF, Bodao, BI, et al. Diagnosis and management of ingested foreign bodies: a 10-year experience. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:30.

5. Nadir, A, Sahin, E, Nadir, I, et al. Esophageal foreign bodies: 177 cases. Dis Esophagus. 2011;24:6.

6. Hess, GP. An approach to throat complaints: foreign body sensation, difficulty swallowing, and hoarseness. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1987;5:313.

7. Kelley, JE, Leech, MH, Carr, MG. A safe and cost-effective protocol for the management of esophageal coins in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:898.

8. Ricote, G, Torre, LR, DeAyala, VP, et al. Fiber endoscopic removal of foreign bodies of the upper part of the gastrointestinal tract. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985;160:499.

9. Webb, WA. Management of foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:204.

10. Kay, M, Wyllie, R. Pediatric foreign bodies and their management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2005;7:212.

11. McGahren, ED. Esophageal foreign bodies. Pediatr Rev. 1999;20:129.

12. Conway, WC, Sugawa, C, Ono, H, et al. Upper GI foreign body: an adult urban emergency hospital experience. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:455.

13. Taylor, R. Esophageal foreign bodies. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1987;5:301.

14. Lao, J, Bostwich, HE, Berezin, S, et al. Esophageal food impaction in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19:402.

15. Hurtado, CW, Furuta, GT, Kramer, RE. Etiology of esophageal food impactions in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:43.

16. Conway, WC, Sugawa, C, Ono, H, et al. Upper GI foreign body: an adult urban emergency hospital experience. Surg Endosc. 2006;21:455.

17. Conners, GP, Cobaugh, DJ, Feinberg, R, et al. Home observation for asymptomatic coin ingestion: acceptance and outcomes. The New York State Poison Control Center Coin Ingestion Study Group. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:213.

18. Soprano, JV, Fleisher, GR, Mandl, KD. The spontaneous passage of esophageal coins in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1073.

19. Waltzman, M. Management of esophageal coins. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:367.

20. Macpherson, RI, Hill, JG, Othersen, HB, et al. Esophageal foreign bodies in children: diagnosis, treatment, and complications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:919.

21. Conners, GP. Esophageal coin ingestion: going low tech. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:373.

22. Kuhns, DW, Dire, DJ. Button battery ingestions. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:293.

23. Litovitz, TL. Battery ingestions: product accessibility and clinical course. Pediatrics. 1985;75:469.

24. Litovitz, TL, Schmitz, BF. Ingestion of cylindrical and button batteries: an analysis of 2382 cases. Pediatrics. 1992;89:747.

25. Meislin, H, Kobernick, M. Corn chip laceration of the esophagus and evaluation of suspected esophageal perforation. Ann Emerg Med. 1983;12:455.

26. Schwartz, GF, Polsky, HS. Ingested foreign bodies of the gastrointestinal tract. Am Surg. 1976;42:236.

27. Selivanov, V, Sheldon, GF, Cello, JP, et al. Management of foreign body ingestion. Ann Surg. 1984;199:187.

28. Bizakis, JG, Segas, J, Haralambos, S, et al. Retropharyngeal abscess associated with a swallowed bone. Am J Otolaryngol. 1993;14:354.

29. Macchi, V, Porzionato, A, Bardini, R, et al. Rupture of ascending aorta secondary to esophageal perforation by fish bone. J Forensic Sci. 2008;53:1181.

30. Zhiang, X, Liu, J, Li, J, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of 32 cases of aortoesophageal fistula due to esophageal foreign body. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:267.

31. Sharieff, GQ, Brousseau, TJ, Bradshaw, JA, et al. Acute esophageal coin ingestions: is immediate removal necessary? Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33:859.

32. Gilchrist, BF, Valerie, EP, Nguyen, M, et al. Pearls and perils in the management of prolonged, peculiar, penetrating esophageal foreign bodies in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1429.

33. Wu, WT, Chiu, CT, Kuo, CJ, et al. Endoscopic management of suspected esophageal foreign body in adults. Dis Esophagus. 2011;24:131.

34. Stack, LB, Munter, DW. Foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1996;14:493.

35. Conners, GP, Chamberlain, JM, Ochsenschlager, DW. Symptoms and spontaneous passage of esophageal coins. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:36.

36. Hodge, D, Tecklenberg, F, Fleisher, G. Coin ingestion: does every child need a radiograph? Ann Emerg Med. 1985;14:443.

37. Bailey, P. Pediatric esophageal foreign body with minimal symptomatology. Ann Emerg Med. 1983;12:452.

38. Nandi, P, Ong, GB. Foreign bodies in the esophagus: review of 2394 cases. Br J Surg. 1978;65:5.

39. Louie, JP, Alpern, ER, Windreich, RM. Witnessed and unwitnessed esophageal foreign bodies in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21:582.

40. Blair, SR, Graber, GM, Cruzzavala, JL, et al. Current management of esophageal impactions. Chest. 1993;104:1205.

41. Mosca, S, Manes, G, Martino, R, et al. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract: report on a series of 414 adult patients. Endoscopy. 2001;33:692.

42. Pudar, G, Vlaski, L. Esophageal foreign bodies: retrospective study in 203 cases. Med Pregl. 2010;63:254.

43. Ngan, JH, Fok, PJ, Lai, EC, et al. A prospective study of fish bone ingestions: experience with 358 patients. Ann Surg. 1990;211:459.

44. Doraiswamy, NV, Baig, H, Hallam, L. Metal detector and swallowed metal foreign bodies in children. J Accid Emerg Med. 1999;16:123.

45. Ryan, J, Perez-Avila, CA, Cherukuri, A, et al. Using a metal detector to locate a swallowed ring pull. J Accid Emerg Med. 1995;12:64.

46. Carr, AJ. Radiology of fish bone foreign bodies in the neck. J Laryngol Otol. 1987;10:407.

47. Eli, SR. View from within—radiology in focus. Radiopacity of fish bones. J Laryngol Otol. 1989;103:1224.

48. Palme, CE, Lowinger, D, Peterson, AJ. Fish bones at the cricopharyngeus: a comparison of plain film radiology and computed tomography. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1955.

49. Watanabe, K, Kikuchi, T, Katori, Y, et al. The usefulness of computed tomography in the diagnosis of impacted fish bones in the oesophagus. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:360.

50. Derowe, A, Ophir, D. Negative findings of esophagoscopy for suspected foreign bodies. Am J Otolaryngol. 1994;15:41.

51. Eliashar, R, Dano, I, Dangoor, E, et al. Computed tomography diagnosis of esophageal bone impaction: a prospective study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108:708.

52. Evans, RM, Ahuja, A, Rhys, WS, et al. The lateral neck radiograph in suspected impacted fish bones: does it have a role? Clin Radiol. 1992;46:121.

53. Marais, J, Mitcell, R, Wigthman, AJA. The value of radiographic assessment for oropharyngeal foreign bodies. J Laryngol Otol. 1995;109:452.

54. Goh, BK, Tan, YM, Lin, SE, et al. CT in the preoperative diagnosis of fish bone perforation of the gastrointestinal tract. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:710.

55. Kaxam, JK, Coll, D, Maltx, C. Computed tomography for the diagnosis of esophageal foreign body. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:897.

56. Lim, CT, Tan, KP, Stanley, RE. Cricoid calcification mimicking an impacted foreign body. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1993;102:735.

57. Talmi, YP, Bedrin, L, Ofer, A, et al. Prevertebral calcification masquerading as a hypopharyngeal foreign body. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:435.

58. Zoller, H, Bowie, HR. Foreign bodies of food passages versus calcifications of laryngeal cartilages. Arch Otolaryngol. 1957;65:474.

59. Weber, AL. Radiology of the larynx. In: Taveras JM, Ferrucci JT, eds. Radiology-Diagnosis-Imaging-Intervention. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1989.

60. Schild, JA, Snow, JB. Esophagology. In: Ballenge BB, Snow JB, eds. Otorhinolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery. 15th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996:1221.

61. Ekberg, O. Normal anatomy and techniques of examination of the esophagus: fluoroscopy, CT, MRI, and scintigraphy. In: Freeny PC, Stevenson GW, eds. Margulis and Burhenne’s Alimentary Tract Radiology. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1994:183.

62. Ginsberg, GG. Management of ingested foreign objects and food bolus impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:33.

63. Shrime, MG, Johnson, PE, Syewart, M. Cost-effective diagnosis of ingested foreign bodies. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:785.

64. Braverman, I, Gomore, JM, Polv, O, et al. The role of CT imaging in the evaluation of cervical esophageal foreign bodies. J Otolaryngol. 1993;22:311.

65. Douglas, M, Sistrom, CL. Chicken bone lodged in the upper esophagus: CT findings. Gastrointest Radiol. 1991;16:11.

66. Gamba, JL, Heaston, DK, Ling, D, et al. CT diagnosis of an esophageal foreign body. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983;140:289.

67. Chee, LW, Sethi, DS. Diagnostic and therapeutic approach to migrating foreign bodies. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108:177.

68. Eliashar, R, Gross, M, Dano, I, et al. Esophageal fish bone impaction. J Trauma. 2001;50:384.

69. Tsai, YS, Lui, CC. Retropharyngeal and epidural abscess from a swallowed fish bone. Am J Emerg Med. 1997;15:381.

70. Webb, WA, McDaniel, L, Jones, L. Foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract: current management. South Med J. 1984;77:1083.

71. Bendig, D. Removal of blunt esophageal foreign bodies by flexible endoscopy without general anesthesia. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140:789.

72. Berggreen, PJ, Harrison, E, Sanowski, RA, et al. Techniques and complications of esophageal foreign body extraction in children and adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:626.

73. Dahshan, AH, Kevan Donovan, G. Bougienage versus endoscopy for esophageal coin removal in children. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:454.

74. Calkins, CM, Christians, KK, Sell, LL. Cost analysis in the management of esophageal coins: endoscopy versus bougienage. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:412.

75. Hostetler, MA, Barnard, JA. Removal of esophageal foreign bodies in the pediatric ED: is ketamine an option? Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:96.

76. Ferrucci, J, Long, J. Radiologic treatment of esophageal food impaction using intravenous glucagon. Radiology. 1977;125:25.

77. Friedland, G. The treatment of acute esophageal food impaction. Radiology. 1983;149:601.

78. Trenkner, SW, Maglinte, DD, Lehman, GA, et al. Esophageal food impaction: treatment with glucagon. Radiology. 1983;149:401.

79. Colon, V, Grade, A, Pulliam, G, et al. Effect of doses of glucagons used to treat food impaction on esophageal motor function of normal subjects. Dysphagia. 1999;14:27.

80. Mehta, DI, Attia, MW, Quintana, EC, et al. Glucagon use for esophageal coin dislodgement in children: a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:200.

81. Al-Haddad, M, Ward, EM, Scolapio, JS, et al. Glucagon for the relief of esophageal food impaction does it really work? Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:1930.

82. Maglinte, DD. Pharmacoradiologic disimpaction of lower esophageal foreign bodies: should we abandon it? Dysphagia. 1995;10:128.

83. Karanjia, ND, Rees, M. The use of Coca-Cola in the management of bolus obstruction in benign oesophageal stricture. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1993;75:94.

84. Kaszar-Seibert, DJ, Korn, WT, Bindman, DJ, et al. Treatment of acute esophageal food impaction with a combination of glucagons, effervescent agent, and water. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154:533.

85. Bell, AF, Eibling, DE. Nifedipine in the treatment of distal esophageal food impaction [letter]. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114:682.

86. Gibson, MS. Nitroglycerin use in esophageal disorders [letter]. Ann Emerg Med. 1980;9:280.

87. Goldberg, GJ. Emergency department treatment of esophageal obstruction [letter]. Ann Emerg Med. 1980;9:280.

88. Rice, B, Spiegel, P, Dombrowski, P. Acute esophageal food impaction treated by gas-forming agents. Radiology. 1983;146:299.

89. Zimmers, T, Chan, SB, Kouchoukos, PL, et al. Use of gas-forming agents in esophageal food impactions. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:693.

90. Mohammed, S, Hegedus, V. Dislodgement of impacted oesophageal foreign bodies with carbonated beverages. Clin Radiol. 1986;37:589.

91. Cavo, JW, Jr., Koops, HJ, Gryboski, RA. Use of enzymes for meat impactions in the esophagus. Laryngoscope. 1977;87:630.

92. Soprano, JV, Mandl, KD. Four strategies for the management of esophageal coins in children. Pediatrics. 2000;105:5.

93. Jona, JZ, Glicklich, M, Cohen, RD. The contraindications for blind esophageal bougienage for coin ingestion in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1988;23:328.

94. Baral, BK, Joshi, RR, Bhattarai, BK, et al. Removal of coin from upper esophageal tract in children with Magill’s forceps under propofol sedation. Nepal Med Coll J. 2010;12:38.

95. Bhargava, R, Brown, L. Esophageal coin removal by emergency physicians: a continuous quality improvement project incorporating rapid sequence intubation. CJEM. 2011;13:28.

96. Balci, AE, Eren, S, Eren, MN. Esophageal foreign bodies under cricopharyngeal level in children: an analysis of 1116 cases. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2004;3:14.

97. Cetinkursun, S, Savan, A, Semirbaq, S, et al. Safe removal of upper esophageal coins by using Magill forceps: two centers’ experience. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2006;45:71.

98. Bigler, F. The use of a Foley catheter for removal of blunt foreign objects from esophagus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1966;51:759.

99. Dunlap, L. Removal of an esophageal foreign body using a Foley catheter. Ann Emerg Med. 1981;10:101.

100. Campbell, J, Foley, C. A safe alternative to endoscopic removal of blunt esophageal foreign bodies. Arch Otolaryngol. 1983;109:323.

101. Ginaldi, S. Removal of esophageal foreign bodies using a Foley catheter in adults. Am J Emerg Med. 1985;3:64.

102. McGuirt, W. Use of a Foley catheter for removal of esophageal foreign bodies: a survey. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1982;91:599.

103. Nixon, GW. Foley catheter method of esophageal foreign body removal: extension of applications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;132:441.

104. Little, DC, Shah, SR, Peter, SD. Esophageal foreign bodies in the pediatric population: our first 500 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:914.

105. Campbell, JB, Condon, VR. Catheter removal of blunt esophageal foreign bodies in children: survey of the Society for Pediatric Radiology. Pediatr Radiol. 1989;19:361.

106. Harned, RK, Strain, JD, Hay, TC, et al. Esophageal foreign bodies: safety and efficacy of Foley catheter extraction of coins. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:443.

107. Morrow, SE, Bickler, SW, Kennedy, AP, et al. Balloon extraction of esophageal foreign bodies in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:266.

108. Schunk, JE, Harrison, AM, Corneli, HM, et al. Fluoroscopic Foley catheter removal of esophageal foreign bodies in children: experience with 415 episodes. Pediatrics. 1994;94:709.

109. Davidoff, E, Towne, JB. Ingested foreign bodies. N Y State Med J. 1975;75:1003.

110. Aiken, DW. Coins in the esophagus: a departure from conventional therapy. Mil Med. 1965;130:182.

111. Bonadio, WA, Jona, JZ, Glicklich, M, et al. Esophageal bougienage technique for coin ingestion in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1988;23:917.

112. Emslander, HC, Bonadio, W, Klatzo, M. Efficacy of esophageal bougienage by emergency physicians in pediatric coin ingestion. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27:726.

113. Conners, GP. A literature-based comparison of three methods of pediatric esophageal coin removal. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1997;13:154.

114. Conners, GP, Chamberlain, JM, Weiner, PR. Pediatric coin ingestion: a home-based survey. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13:638.

115. Mohiuddin, S, Siddiqui, MS, Mayhew, JF. Esophageal foreign body aspiration presenting as asthma in the pediatric patient. South Med J. 2004;97:93.

116. Smith, SA, Conners, GP. Unexpected second foreign bodies in pediatric esophageal coin ingestions. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1998;14:261.

117. Lee, JH, Lee, JS, Kim, MJ, et al. Initial location determines spontaneous passage of foreign bodies from the gastrointestinal tract in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;4:284.

118. Waltzman, ML, Baskin, M, Wypij, D, et al. A randomized clinical trial of the management of esophageal coins in children. Pediatrics. 2005;116:614.

119. Cantu, S, Conners, GP. Esophageal coins: are pennies different? Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2001;40:677.

120. Cantu, S, Conners, GP. The esophageal coin: is it a penny? Am Surg. 2002;68:417.

121. Lue, AJ, Fang, WD, Manolidis, S. Use of plain radiography and computed tomography to identify fish bone foreign bodies. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:435.

122. Sundgren, PC, Burnett, A, Maly, PV. Value of radiography in the management of possible fish bone ingestion. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1994;103:628.

123. Litovitz, T, Whitaker, N, Clark, L, et al. Emerging battery-ingestion hazard: clinical implications. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1168.

124. Litovitz, T, Whitaker, N, Clark, L. Preventing battery ingestions: an analysis of 8648 cases. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1178.

125. Bass, DH, Millar, AJW. Mercury absorption following button battery ingestion. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:1541.

126. Suita, S, Ohgami, H, Yakabe, S, et al. The fate of swallowed button batteries in children. Z Kinderchir. 1990;45:212.

127. Chan, YL, Chang, SS, Kao, KL, et al. Button battery ingestion: an analysis of 25 cases. Chang Gun Med J. 2002;25:169.

128. Kulig, K, Rumack, CM, Duggy, JP. Disk battery ingestion, elevated urine mercury levels, and enema removal of battery fragments. JAMA. 1983;249:2502.