Erythroderma

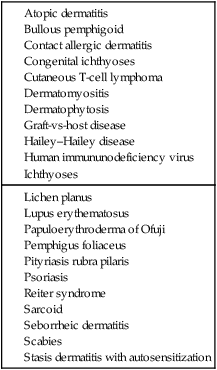

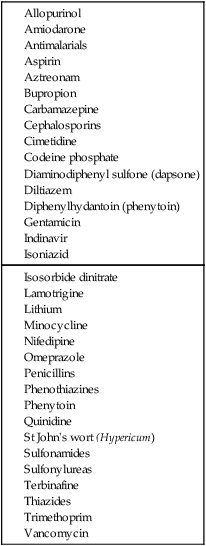

Erythroderma (exfoliative dermatitis) is defined as inflammation of at least 90% of the body surface, characterized by generalized erythema and a variable degree of scaling or desquamation. Erythroderma is commonly the result of generalization of a pre-existing chronic dermatosis or a systemic disease (see Table 75.1). These include genodermatoses and congenital disorders such as severe ichthyoses and ichthyosiform erythrodermas; severe cases of dermatoses such as psoriasis, atopic or seborrheic or contact allergic dermatitis; cutaneous T-cell lymphoma; allergic reactions to drugs (see Table 75.2); and internal malignancies (especially lymphoma and other lymphoreticular malignancies). Some cases develop without any apparent trigger and erythroderma remains ‘idiopathic’ in up to 25% of the cases.

Specific investigations

Second-line therapies

Third-line therapies

Bed rest in hospital

Bed rest in hospital Emollients

Emollients Topical corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids Psoralen and UVA (PUVA)

Psoralen and UVA (PUVA) Systemic corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids PUVA with retinoid

PUVA with retinoid Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine Cytotoxic drugs/antimetabolites

Cytotoxic drugs/antimetabolites Systemic retinoids

Systemic retinoids Extracorporeal photochemotherapy

Extracorporeal photochemotherapy UVA1 phototherapy

UVA1 phototherapy Topical calcipotriol

Topical calcipotriol Topical tacrolimus

Topical tacrolimus Erythromycin

Erythromycin Photopheresis and interferon

Photopheresis and interferon Infliximab

Infliximab Etanercept

Etanercept Alemtuzumab

Alemtuzumab Daclizumab

Daclizumab Bexarotene

Bexarotene