16

Erythema Multiforme, Stevens–Johnson Syndrome, and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

Erythema Multiforme

• Self-limited, but potentially recurrent, disease.

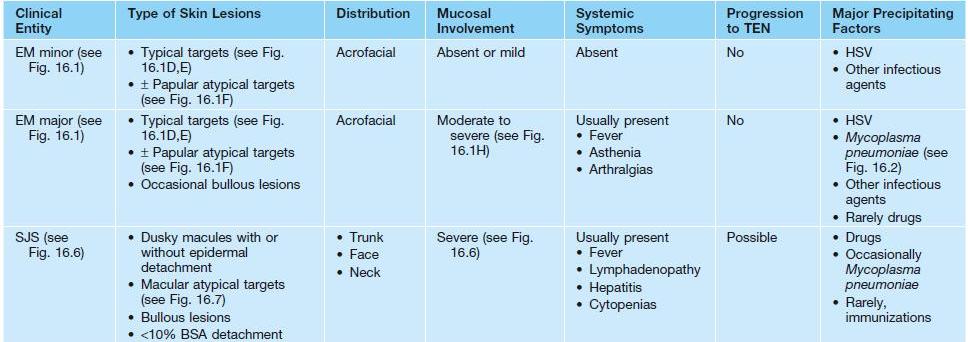

• Two forms: erythema multiforme (EM) major and EM minor (Table 16.1).

Table 16.1

Clinical features that distinguish erythema multiforme (EM) from Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and SJS–TEN overlap.

• Both forms have an abrupt onset of papular ‘target’ lesions that favor acrofacial sites.

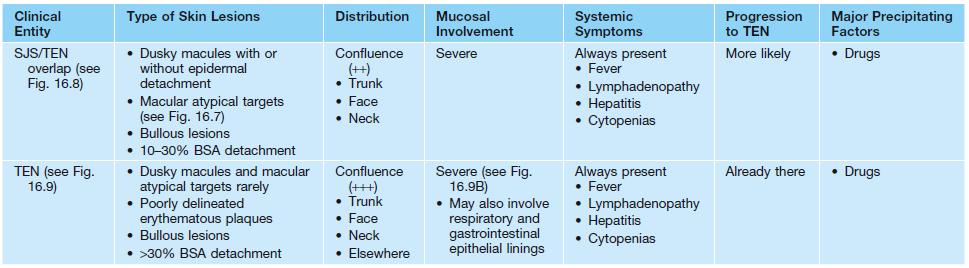

• Two types of target lesions: (1) typical targets, with at least three different zones; (2) atypical papular targets, with only two different zones and/or a poorly defined border (Fig. 16.1).

Fig. 16.1 Phenotypic variety in lesions of erythema multiforme (EM). A Edematous/urticarial. B Urticarial with central crusting. C Erythematous plaques with dusky centers; coalescence of the lesions leads to a well-defined polycyclic outline. D, E Typical (classic) target lesions on the palms and dorsal hand, with three zones of color change (‘bull’s eye’); note the central vesicles in (D). F Atypical papular target lesions on the upper forehead mixed with more typical target lesions on the lower forehead. G Isomorphic response. H Mucosal involvement in EM major. Typical target lesions are seen as well as serous crusting of the vermilion lips and eyelid margin. At the margin of the serous crusting of the lip, there are two zones of color with a polycyclic outline. A, D, G, Courtesy, William Weston, MD.

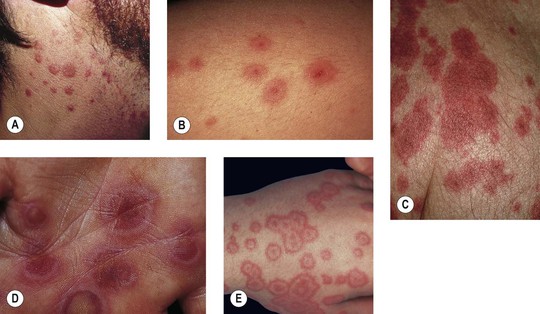

• Preceding HSV infection is most common precipitating factor; less often other preceding infections, in particular Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Table 16.2; Fig. 16.2); rarely drug exposure.

Table 16.2

Precipitating factors in erythema multiforme.

This is a non-exhaustive list based primarily on case reports and small series of cases. The most common causes are in bold.

Fig. 16.2 Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated mucositis (MPAM). MPAM is an extrapulmonary manifestation of M. pneumoniae infection that falls along the spectrum of EM major or SJS. In MPAM, there may be isolated mucosal lesions (e.g. ocular, oral, and urogenital) or a combination of mucosal and minimal skin lesions. Note the hemorrhagic and serous crusting of the vermilion lips (A) in this 12-year-old male with M. pneumoniae infection who presented with isolated oral and genital (B) lesions. A, B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Diagnosis based on clinicopathologic correlation and not solely histopathologic findings.

• EM is a distinct disorder from Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) (see Table 16.1).

• EM does not progress to TEN.

• DDx: giant urticaria (Fig. 16.3; Table 16.3), morbilliform drug reaction (Fig. 16.4), multiple fixed drug eruption (FDE), acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy, Kawasaki disease, small vessel vasculitis, Rowell’s syndrome, GVHD, polymorphic light eruption (PMLE).

Fig. 16.3 Giant annular urticaria. This form of urticaria is sometimes referred to as urticaria multiforme because lesions can resolve with faint purpura. It does not represent erythema multiforme but is rather a form of urticaria. Refer to Table 16.3 for clinical ways to distinguish urticaria from erythema multiforme. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Table 16.3

Differences between urticaria and erythema multiforme.

| Urticaria | Erythema Multiforme |

| Central zone is normal skin | Central zone is damaged skin (dusky, bullous, or crusted) |

| Lesions are transient, lasting less than 24 hours* | Lesions ‘fixed’ for at least 7 days |

| New lesions appear daily | All lesions appear within first 72 hours |

| Associated with swelling of face, hands, or feet (angioedema) | No edema |

* Confirmed with ‘circle test’ – circle a given urticarial lesion with pen/marker and re-check to see if still there in 24 hours.

Stevens–Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN)

• SJS and TEN are considered the same disease, but along a clinical spectrum of severity and distinct from EM (see Table 16.1).

• Most likely etiology for both is an adverse reaction to a medication.

• Most common culprit drugs (Table 16.4): NSAIDs, antibiotics (in particular, sulfonamides and penicillins), anticonvulsants, and allopurinol.

Table 16.4

Medications most frequently associated with Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).

For a complete updated list of drugs associated with SJS and TEN, refer to Litt JZ, 2010. Litt’s Drug Eruptions and Reactions Manual, 16th ed. London: Informa Healthcare.

Allopurinol

Aminopenicillins

Amithiozone (thioacetazone)*,†

Antiretroviral drugs

Barbiturates

Carbamazepine

Phenytoin anticonvulsants

Lamotrigine

Piroxicam

Sulfadoxine†

Sulfasalazine

Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole

* Not available in the United States.

† Antibacterial.

‡ Sedative/hypnotic.

§ Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

• In some patients there may be an underlying genetic predisposition, e.g.

– Allopurinol-induced SJS/TEN associated with HLA-B*58:01 allele.

– Carbamazepine-induced SJS associated with HLA-B*15:02 in Asian populations.

– Carbamazepine-induced SJS associated with HLA-A*31:01 allele in Europeans.

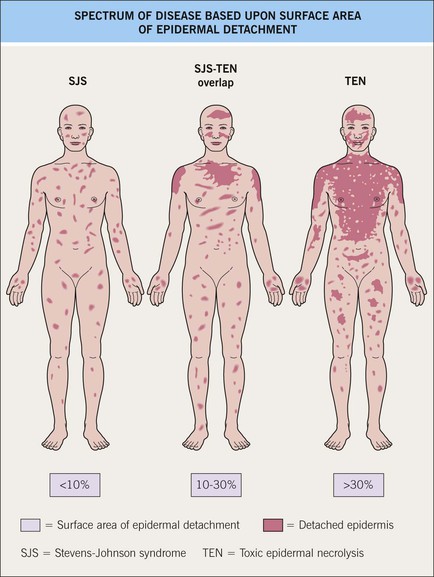

• SJS is characterized by <10% body surface area (BSA) epidermal detachment, SJS–TEN overlap by 10–30% BSA epidermal detachment, and TEN by >30% BSA epidermal detachment (Fig. 16.5).

Fig. 16.5 Spectrum of disease based on surface area of epidermal detachment. Adapted from Bastuji-Garin S, et al. Arch Dermatol. 129:92, 1993.

• Onset usually 7–21 days after starting culprit medication.

• Painful erythema and erosions of buccal, ocular, and genital mucosa in >90% of patients (Fig. 16.6).

Fig. 16.6 Mucosal involvement in Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS). A Conjunctival erosions and exudate. B Hemorrhagic crusts and denudation of the lips in a child with SJS secondary to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole therapy; note the bullous cutaneous lesions. C Erosions of the genital mucosa. A, B, Courtesy, William Weston, MD.

• Morphologic progression of skin lesions: dusky red or purpuric macules (macular atypical targets) of various sizes and shapes that begin to coalesce (Fig. 16.7); the gray-colored centers become wrinkled and begin to slough due to the development of flaccid bullae and poor attachment of the necrotic epidermis (likened to wet cigarette paper) (Fig. 16.8); the result is raw, denuded, bright red dermis (scalding) (Fig. 16.9).

Fig. 16.7 Cutaneous features of toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Characteristic dusky red color of the early macular eruption in TEN. Lesions with this color often progress to full-blown necrolytic lesions with dermal–epidermal detachment. Note the atypical macular target lesions in areas without confluence, e.g. around the umbilicus and left flank.

Fig. 16.8 Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) versus SJS–TEN overlap. A In addition to mucosal involvement and numerous dusky lesions with flaccid bullae, there are areas of coalescence and multiple sites of epidermal detachment. Because the latter involved >10% body surface area, the patient was classified as having SJS–TEN overlap. B Close-up of epidermal detachment, whose appearance has been likened to wet cigarette paper.

Fig. 16.9 Clinical features of toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). A Detachment of large sheets of necrolytic epidermis (>30% body surface area), leading to extensive areas of denuded skin. A few intact bullae are still present. B Hemorrhagic crusts with mucosal involvement. C Epidermal detachment of palmar skin. B, C, Courtesy, Lars E. French, MD.

• Unpredictable course; worse prognosis in the elderly and with increasing BSA involvement (Table 16.5).

Table 16.5

SCORTEN scale.

| Prognostic Factors | Points |

| Age >40 years | 1 |

| Heart rate >120 bpm | 1 |

| Cancer or hematologic malignancy | 1 |

| BSA involved on day 1 above 10% | 1 |

| Serum urea level (>10 mmol/l) | 1 |

| Serum bicarbonate level (<20 mmol/l) | 1 |

| Serum glucose level (>14 mmol/l) | 1 |

| SCORTEN | Mortality Rate (%) |

| 0–1 | 3.2 |

| 2 | 12.1 |

| 3 | 35.8 |

| 4 | 58.3 |

| ≥5 | 90 |

• Mortality rate in SJS is 1–5% and in TEN, 25–35%.

• Most important factor in improving outcome is withdrawal of culprit medication.

• DDx: EM, drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD), acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), severe acute GVHD, Rowell’s syndrome, paraneoplastic pemphigus; in children can consider staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) and Kawasaki disease.

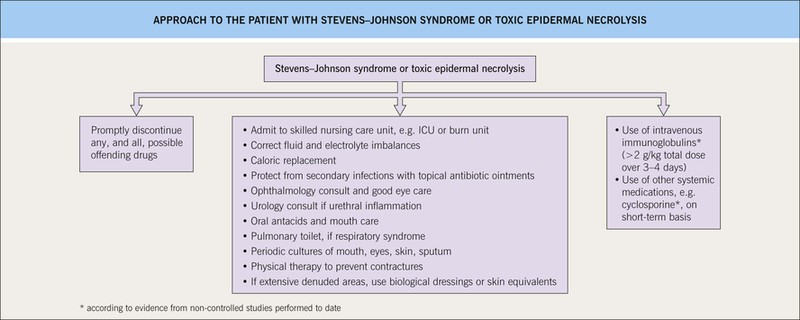

• Rx: stop the culprit medication, rapid initiation of supportive care, specific therapy (no evidence-based treatment) (Fig. 16.10).

Fig. 16.10 Management of the patient with Stevens–Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis. ICU, intensive care unit.

• Specific therapies that have the potential to block keratinocyte apoptosis, such as IVIg, may provide added benefit over supportive care (Fig. 16.11).

For further information see Ch. 20. From Dermatology, Third Edition.