Chapter 67 Epilepsies

Seizures and Epilepsy Definitions

Seizures are transient events that include symptoms and/or signs of abnormal excessive hypersynchronous activity in the brain (Fisher et al., 2005). In 2005, the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE) proposed a definition of epilepsy as a disorder of the brain characterized by an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizures and by the neurobiological, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences of this condition (Fisher et al., 2005). Acute symptomatic seizures provoked by metabolic or toxic derangements or occurring acutely in the setting of head trauma or stroke do not define epilepsy.

The traditional definition of epilepsy requires at least two unprovoked seizures. The definition proposed by the ILAE in 2005 suggested that one epileptic seizure is sufficient to diagnose epilepsy if there is additional enduring alteration in the brain that increases the likelihood of future seizures, but the proposal did not specify what evidence is sufficient to define such an enduring alteration. The proposed definition has been controversial and has not been widely accepted (Beghi et al., 2010). The definition of epilepsy used in this chapter requires at least two unprovoked seizures, so a single unprovoked seizure is insufficient to define epilepsy.

In 2001, the ILAE proposed a diagnostic scheme for the classification of seizures and epilepsy (Engel, 2001). The scheme recommended axes that are helpful concepts in the evaluation of patients with epilepsy:

Ictal Phenomenology

Glossary of Seizure Terminology and Other Definitions

The terms frequently used in the description of seizures follow. Whenever possible, the definition is derived from the glossary of descriptive terminology for ictal semiology, reported by the ILAE task force on classification and terminology (Blume et al., 2001). The term ictal semiology means the signs and symptoms associated with seizures.

Automatisms can be described by the part of the body affected. Some of the most common are oroalimentary automatisms, which include lip smacking, chewing, swallowing, and other mouth movements. Ictal spitting and ictal drinking can be considered forms of oroalimentary automatisms. Automatisms affecting the distal extremities are manual or pedal. Manual or pedal automatisms can be bilateral or unilateral. Gestural automatisms include extremity movements such as those used to enhance speech. More recently introduced categories for upper extremity automatisms are manipulative and non-manipulative (Kelemen et al., 2010). Manipulative automatisms involve picking and fumbling motions, typically reflecting interaction with the environment. Non-manipulative upper extremity automatisms tend to be rhythmic and do not involve interaction with the environment. Distal non-manipulative upper-extremity automatisms have been described with the acronym RINCH (rhythmic ictal nonclonic hand) movements (Lee et al., 2006). Hyperkinetic automatisms imply an inappropriately rapid sequence of movements that predominantly involve axial and proximal limb muscles. The resulting motion can be thrashing, rocking, pelvic thrusting, kicking, or bicycling motions. Gelastic refers to abrupt laughter or giggling, while dacrystic refers to abrupt crying, both inappropriate.

Classification of Seizures

Two classifications developed by the ILAE continue to be used widely: the Clinical and Electroencephalographic Classification of Epileptic Seizures published in 1981 (Commission on Classification and Terminology, 1981) (Box 67.1) and the Classification of Epilepsies and Epileptic Syndromes introduced in 1989 (Commission on Classification and Terminology, 1989) (Box 67.2). Revisions to these classifications have been recommended based on advances made in the last 3 decades (Berg et al., 2010; Engel, 2001; Engel, 2006). The major recommended revisions are outlined later in this section, but what follows will focus on the 1981 and 1989 classifications, because these classifications are still used widely for clinical management and research and will likely continue to be used in the future.

Box 67.1

International League Against Epilepsy Classification of Epileptic Seizures

From Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy, 1981. Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia 22, 489-501.

Box 67.2

International League Against Epilepsy Classification of Epilepsies and Epileptic Syndromes

1. Localization-related (focal, local, partial) epilepsies and syndromes

2. Generalized epilepsies and syndromes

3. Epilepsies and syndromes undetermined as to whether they are focal or generalized

From Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy, 1989. Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia 30, 389-399.

One important criticism of the 1981 classification is that it requires both clinical and electroencephalographic (EEG) information, and assumptions on correlation of clinical and EEG features may be incorrect. A purely semiological classification of epileptic seizures was proposed, based solely on observed clinical features (Lüders et al., 1998). The semiological seizure classification includes somatotopic modifiers to define the somatotopic distribution of the manifestations and allows demonstration of evolution of ictal manifestations using arrows to link sequential manifestations (Lüders et al., 1998). Although this classification was not adopted by the ILAE, it is considered an optional seizure classification system that is useful for localization purposes in epilepsy surgery centers.

The latest revision of the seizure classification has maintained the division of seizures based on generalized or focal onset but has recommended replacing partial with focal. It also updated the definition of focal seizures as “originating within networks limited to one hemisphere,” with the possibility of the seizures being discretely localized or more widely distributed, and possibly originating in subcortical structures. Generalized seizures were defined as “originating at some point within, and rapidly engaging, bilaterally distributed networks,” which do not necessarily include the entire cortex (Berg et al., 2010). The revised concepts acknowledge that generalized seizures can be asymmetrical and that individual seizures may appear to have a localized onset, but the location and laterality of that onset will vary from seizure to seizure (Berg et al., 2010).

Seizure Types

Partial Seizures

Simple Partial Seizures

The most recent recommendation of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology suggested eliminating the term simple partial. Instead, it recommended descriptors of focal seizures according to degree of impairment during a seizure. Seizures without impairment of consciousness or awareness are divided into those with observable motor or autonomic components and those only involving subjective sensory or psychic phenomena (Berg et al., 2010).

Partial Seizures Evolving to Generalized Tonic-Clonic Activity

These seizures may start as simple partial, complex partial, or simple partial evolving to complex partial. The transition to secondary generalization usually involves versive head turning in a direction contralateral to the hemisphere of seizure onset, and focal or lateralized tonic or clonic motor activity. The pattern of evolution may be clonic-tonic-clonic in some instances. The generalized tonic phase may be asymmetrical, with flexion on one side and extension on the other. This has been called figure-of-4 posturing (Kotagal et al., 2000). Some asymmetry and asynchrony may also occur in the clonic phase, resulting in a slight degree of side-to-side head jerking (Niaz et al., 1999). The evolution from tonic to clonic activity is gradual and not always simultaneous in all affected body parts. A phase of high-frequency tremor has been referred to as the tremulous or vibratory phase of the seizure (Theodore et al., 1994). Clonic activity typically decreases in frequency over time, with longer intervals between jerks towards the termination of the seizure. The clonic activity may end on one side of the body first, so that clonic activity may then appear lateralized to one side. In addition, there may be a late head turn ipsilateral to the hemisphere or seizure origin (Wyllie et al., 1986). After the motor activity stops, the individual is usually limp and has a loud snoring respiration often referred to as stertorous respiration. During the course of recovery, there may be variable agitation. The speed of recovery is expected to be slower with longer and more severe seizures.

Partial Seizure Semiology in Relation to Localization

Partial Seizures of Temporal Lobe Origin

Temporal lobe seizures most often are of mesial temporal amygdalohippocampal origin, in association with the pathology of hippocampal sclerosis. Patients commonly have isolated auras, and complex partial seizures tend to start with an aura. The most common aura is an epigastric sensation frequently with a rising character (French et al., 1993). Other auras occur less commonly and include fear, anxiety, and other emotions, déjà vu and jamais vu, nonspecific sensations, and autonomic experiences such as palpitation and gooseflesh. Olfactory and gustatory auras are uncommon and more likely with tumoral mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (MTLE).

Complex partial seizures may start with an aura or with altered consciousness. With nondominant temporal lobe seizures, the patient may remain responsive and verbally interactive. However, recollection of conversations is unusual. Altered consciousness is often associated with an arrest of motion and speech. Speech arrest is not synonymous with aphasia and does not distinguish dominant and nondominant temporal lobe seizures. Automatisms are one of the most prominent manifestations, and oroalimentary automatisms are the most prevalent. Extremity automatisms also occur and are most commonly manipulative, with picking or fumbling. This type of automatism is not of direct lateralizing value. However, the contralateral upper extremity is commonly involved in dystonic posturing (Kotagal et al., 1989) or milder degrees of posturing and immobility (Fakhoury and Abou-Khalil, 1995; Williamson et al., 1998). This reduces the availability of the contralateral arm for automatisms, so manipulative automatisms tend to be ipsilateral, involving the unaffected upper extremity. Nonmanipulative automatisms typically consist of rhythmic movements either distally or proximally. These tend to be contralateral, often preceding overt dystonic posturing (Lee et al., 2006). Head turning occurs commonly. Early head turning is not usually forceful. It typically occurs at the same time as dystonic posturing and is most often ipsilateral (Fakhoury and Abou-Khalil, 1995; Williamson et al., 1998). Late head turning most often occurs during evolution to generalized tonic-clonic activity. This is usually contralateral to the side of seizure origin (Williamson et al., 1998). Well-formed ictal speech may occur during seizures of nondominant temporal lobe origin (Gabr et al., 1989). Verbal output may at times be tinged with a fearful tone. Complex partial seizures of temporal lobe origin usually last between 30 seconds and 3 minutes. Postictal manifestations may be helpful in lateralizing the seizure onset. Postictal aphasia is commonly seen after dominant temporal lobe seizures (Gabr et al., 1989). In one study, such patients were unable to read a test sentence correctly in the first minute after seizure termination, but patients with nondominant right temporal lobe origin were able to read the test sentence within 1 minute of seizure termination (Privitera et al., 1991).

Seizures of lateral temporal origin or neocortical temporal origin are much less common than those of mesial temporal origin. They cannot be reliably distinguished based on their semiology, but certain features can help distinguish them. Auditory auras are the most common auras referable to the lateral temporal cortex, usually implying involvement of the Heschl gyrus. Other types of auras referable to the lateral temporal cortex are vertiginous and complex visual hallucinations (usually posterior temporal). Oroalimentary automatisms are less common, and the pattern of contralateral dystonic posturing and ipsilateral extremity automatisms is also less common (Dupont et al., 1999). Early contralateral or bilateral facial twitching may be seen as a result of propagation to the frontal operculum (Foldvary et al., 1997). Seizures of lateral temporal origin tend to be shorter in duration and have a greater tendency to evolve to generalized tonic-clonic activity than seizures of mesial temporal origin.

Partial Seizures of Frontal Lobe Origin

Many different seizure types can originate in the frontal lobe, depending on site of seizure origin and propagation. Simple partial seizures can be motor with focal clonic activity, can originate in the motor cortex, or can be the result of spread to the motor cortex. These seizures may or may not have a Jacksonian march. Asymmetrical tonic seizures or postural seizures are usually related to involvement of the supplementary motor area in the mesial frontal cortex anterior to the motor strip. The best-known posturing pattern is the fencing posture in which the contralateral arm is extended and the ipsilateral arm is flexed. Tonic posturing may involve all four extremities and is occasionally symmetrical. When these seizures originate in the supplementary motor area, consciousness is usually preserved (Morris et al., 1988). Supplementary motor seizures are an important exception to the rule that bilateral motor activity during a seizure should be associated with loss of consciousness. Supplementary motor seizures are usually short in duration and frequently arise out of sleep. They tend to occur in clusters and may be preceded by a sensory aura referable to the supplementary sensory cortex. The pattern of posturing described with supplementary motor area seizures can occur as a result of seizure spread to the supplementary motor area from other regions of the brain. In that case, consciousness is frequently impaired. Subjective simple partial seizures may also occur with frontal lobe origin, the most common being a nonspecific cephalic aura.

Complex partial seizures of frontal lobe origin tend to be very peculiar. They may be preceded by a nonspecific aura or they may start abruptly, often out of sleep. Their most characteristic features are hyperkinetic automatisms with frenzied behavior and agitation (Jobst et al., 2000; Williamson et al., 1985). There may be various vocalizations including expletives. The manifestations can be so bizarre as to suggest a psychiatric origin. The seizure duration is short, sometimes less than 30 seconds, and postictal manifestations are brief or nonexistent, further adding to the risk of misdiagnosis as psychogenic seizures. Frontal lobe complex partial seizures arise predominantly from the orbitofrontal region and from the mesial frontal cingulate region. However, they can arise from other parts of the frontal lobe and even from outside the frontal lobe, usually reflecting seizure propagation to the frontal lobe. It may be difficult to determine the region of origin in the frontal lobe based on the seizure manifestations. It has been suggested that the presence of tonic posturing on one side points to a mesial frontal origin, as does rotation along the body axis, which sometimes leads to turning prone during the seizure (Leung et al., 2008; Rheims et al., 2008).

Frontal opercular seizures originating in the frontal operculum are associated with profuse salivation, oral facial apraxia, and sometimes facial clonic activity (Williamson and Engel, 2008). Seizures originating in the dorsolateral frontal lobe may involve tonic movements of the extremities and versive deviation of the eyes and head. The head deviation preceding secondary generalization is contralateral, but earlier head turning can be in either direction (Remi et al., 2011). Seizures may begin with forced thinking. Partial seizures of frontal origin may at times resemble absence seizures (So, 1998). It is important to recognize that seizures originating in the frontal lobe can propagate to the temporal lobe and produce manifestations typical of mesial temporal lobe seizures.

Partial Seizures Originating in the Parietal Lobe

The best-recognized seizure type that originates in the parietal lobe is partial seizure with somatosensory manifestations. The somatosensory experience can be described as tingling, pins and needles, numbness, burning, or pain. The presence of a sensory march is most suggestive of involvement of the primary sensory cortex. Sensory phenomena arising from the second sensory area and the supplementary sensory area are less likely to have a march. Somatosensory auras tend to be contralateral to the hemisphere of seizure origin, but they may be bilateral or ipsilateral when arising from the second or supplementary sensory regions. Other auras of parietal lobe origin are a sensation of movement in an extremity, a feeling of the body bending forward or swaying or twisting or turning, or even a feeling of an extremity being absent (Salanova et al., 1995a; Salanova et al., 1995b). Some patients may complain of inability to move a limb. Vertigo has been reported, as well as visual illusions of objects going away or coming closer or looking larger (Siegel, 2003). Some patients may have initial auras suggesting spread to the occipital or temporal lobe. Seizures involving the dominant parietal lobe may produce aphasic manifestations. Motor manifestations tend to reflect seizure spread to the frontal lobe. These include tonic posturing of the extremities, focal motor clonic activity, and version of the head and eyes (Cascino et al., 1993; Ho et al., 1994; Williamson et al., 1992a). Negative motor manifestations may occur, with ictal paralysis (Abou-Khalil et al., 1995). Seizures may spread to the temporal lobe, producing oroalimentary or extremity automatisms (Siegel, 2003). In one study, motor manifestations were more likely with superior parietal epileptogenic foci, and oroalimentary and extremity automatisms more likely with inferior parietal epileptogenic foci (Salanova et al., 1995a). Visual manifestations seemed more likely with posterior parietal lesions.

Partial Seizures Originating in the Occipital Lobe

The best-recognized occipital lobe seizure semiology is that of simple partial seizures with visual manifestations (Salanova et al., 1992). The most common are elementary visual hallucinations that are described as flashing colored lights or geometrical figures. These are usually contralateral but may move within the visual field. Complex visual hallucinations with familiar faces or people may also occur. Negative symptoms may be reported, with loss of vision in one hemifield. Ictal blindness may involve loss of vision in the whole visual field. Objective seizure manifestations include blinking, nystagmoid eye movements, and versive eye and head deviation contralateral to the seizure focus. This version may occur while the patient is still conscious or could be a component of complex partial seizures.

Seizure manifestations that are related to seizure spread to the temporal or frontal lobe are very common. Oroalimentary automatisms are typical of seizures that spread to the temporal lobe, whereas asymmetrical tonic posturing typifies spread to the frontal lobe; both types of spread can be seen in the same patient (Williamson et al., 1992b). Spread to the temporal or frontal lobe is so common with occipital lobe seizures that it is at times reported in the majority of patients (Jobst et al., 2010b). Ictal semiology cannot distinguish seizures originating from the mesial versus lateral occipital region (Blume et al., 2005). Evolution of occipital seizures to secondary generalization is commonly reported.

Partial Seizures Originating in the Insular Cortex

Insular epilepsy is uncommon and also frequently unrecognized because of the inability to record directly from the insula with scalp electrodes. Subjective symptoms that should suggest seizure origin in the insula include laryngeal discomfort, possibly preceded or followed by a sensation in the chest or abdomen, shortness of breath, and paresthesias around the mouth or also involving other contralateral body parts (Isnard et al., 2004). Objective seizure manifestations include dysarthria/dysphonia, sometimes evolving to complete muteness. With seizure progression in some patients, tonic spasm of the face and upper limb, head and eye rotation, and at times generalized dystonia occur (Isnard et al., 2004). Hypersalivation is also very common and can be impressive. Insular-onset seizures may spread to other brain regions and can be disguised as temporal lobe, parietal lobe, or frontal lobe epilepsy (Ryvlin, 2006; Ryvlin et al., 2006).

Generalized Seizures

Generalized Absence Seizures

Typical absence seizures are characterized by a sudden blank stare with motor arrest, usually lasting less than 15 seconds (Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy, 1981). The individual is usually unresponsive and unaware. The seizure ends as abruptly as it starts, and the patient returns immediately to a baseline level of function with no postictal confusion but may have missed conversation and seems confused as a result. If the only manifestation is altered responsiveness and awareness, with no associated motor component, the absence seizure is classified as simple absence. Most often, generalized absence seizures include mild motor components and are classified as complex absence. The most common motor components are automatisms such as licking the lips or playing with an object that was held in the hand before the seizure. Other motor components include clonic, tonic, atonic, and autonomic manifestations. Clonic activity may affect the eyelids or the mouth. An atonic component may manifest with dropping an object or slight head drop or drooping of the shoulders or trunk. Tonic components may manifest with slight increase in tone.

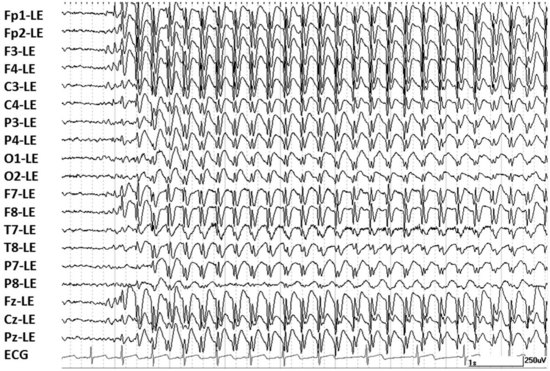

The EEG hallmark of a typical generalized absence seizure is generalized 2.5- to 4-Hz spike-and-wave activity with a normal interictal background (Fig. 67.1). Atypical absence seizures are diagnosed primarily based on a slower (<2.5 Hz) frequency of the EEG spike-and-wave activity. Less important distinctions are that the onset and termination of an atypical absence seizure may be less abrupt and the motor components a bit more pronounced than seen with typical absence seizures. Atypical absence seizures usually occur in individuals with impaired cognitive function. Affected individuals usually have associated seizure types such as generalized tonic, generalized atonic, and generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

Additional generalized absence seizure types recently recognized by the ILAE include myoclonic absences. The key manifestation of these seizures is a prominent rhythmic myoclonus predominantly affecting the limbs (Bureau and Tassinari, 2005b). Otherwise, myoclonic absences resemble typical absence seizures with respect to impairment of consciousness, although this impairment can be only partial. Another related seizure type recently recognized is eyelid myoclonia with absence. The eyelid myoclonia consists of pronounced rhythmic jerking of the eyelids, usually associated with an upward deviation of the eyes and retropulsion of the head (Caraballo et al., 2009). There may or may not be associated generalized spike-and-wave activity on EEG. Absence seizures may evolve to generalized tonic-clonic activity (Mayville et al., 2000).

Generalized Myoclonic Seizures

Myoclonic seizures are muscle contractions lasting a fraction of a second (<250 msec), in association with an ictal EEG discharge (Blume et al., 2001). The myoclonic jerk can be generalized, affecting the whole body, or could affect just the upper extremities or (rarely) the head or trunk, or even the diaphragm. The myoclonic jerks may affect one side of the body at one time, but typically the other side is affected at other times. The jerks can be single or could occur in an arrhythmic cluster. It should be noted that myoclonus is not always epileptic (Faught, 2003). Myoclonus can be generated anywhere along the central nervous system (CNS). Epileptic myoclonus is generated in the cerebral cortex and is usually associated with a single or brief serial spike-and-wave or polyspike-and-wave activity.

Negative myoclonic seizures consist of a very brief pause in muscle activity rather than a brief muscle contraction (Rubboli and Tassinari, 2006). Just as with positive myoclonus, negative myoclonus can be generalized, bilateral with limited distribution, or even focal, typically with shifting lateralization.

Myoclonic seizures may be immediately followed by a loss of tone. The seizure type is called myoclonic-atonic. Historically it was called myoclonic-astatic. The seizures are brief (1 second or less) but may be associated with falls and injuries. The EEG shows generalized spike-and-wave or polyspike-and-wave discharge. The slow wave is prolonged and associated with the electromyographic (EMG) silence characteristic of the atonic phase. Myoclonic seizures may precede a more sustained tonic contraction, and the resultant seizures may be referred to as myoclonic-tonic seizures (Berg et al., 2010). Generalized myoclonic seizures may cluster just before a generalized tonic-clonic seizure occurrence.

Generalized Clonic Seizures

Unlike myoclonic seizures, which are single jerks (but may occur in arrhythmic clusters), each generalized clonic seizure consists of a series of rhythmic jerks. Generalized clonic seizures are uncommon and particularly rare in adults (Noachtar and Arnold, 2000). They are more frequently seen in certain epileptic syndromes of infancy and childhood. For example, clonic seizures are a common seizure type of severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (Dravet syndrome). Clonic seizures are also noted in progressive myoclonic epilepsies.

Generalized Tonic Seizures

Generalized tonic seizures are typically brief seizures, a few seconds to 1 minute. Their onset may be gradual or abrupt. They may be initiated with a myoclonic jerk. They can vary in severity from subtle, with slight increase in neck tone with upward deviation of the eyes, to massive, with involvement of the axial muscles and extremities. Proximal muscles are the most affected. Most commonly there is neck and trunk flexion as well as abduction of the shoulders and flexion of the hips. However extension may also occur. Tonic seizures may be asymmetrical, which could result in turning to one side. The pattern of muscle involvement may change over time so that there may be a change in the position of the limbs over the course of the seizure. Autonomic changes may occur, with tachycardia, pupil dilation, and flushing. Involvement of respiratory muscles could cause apnea and cyanosis. The tonic contraction may end with one or more pauses that result in a few clonic jerks. A postictal state with confusion may occur, but recovery is usually rapid. However, tonic seizures may be followed by atypical absence, resulting in what appears to be a more prolonged postictal state. This has been referred to as tonic-absence seizure (Shih and Hirsch, 2003). Generalized tonic seizures occur most often out of sleep and drowsiness.

Epileptic Spasms

Epileptic spasms have similarities to generalized tonic seizures but a shorter duration that is intermediate between generalized myoclonic and generalized tonic seizures (Blume et al., 2001), with a typical duration of 0.5 to 2 seconds. The pattern of contraction is “diamond-shaped,” with intensity of contraction maximal in the middle of the spasm and less at the beginning and end. Epileptic spasms are also called infantile spasms and salaam attacks. Because their occurrence is not restricted to infants, the preferred current term is epileptic spasms. The classic epileptic spasm involves neck and trunk flexion and arm abduction with a jackknife pattern, but extension may be seen. Epileptic spasms typically occur in clusters recurring every 5 to 40 seconds. In a cluster, the initial spasms may be subtle or mild, increase in intensity as the cluster progresses, and decrease in intensity again toward the end of the cluster (Bleasel and Lüders, 2000).

Generalized Tonic-Clonic Seizures

Generalized tonic-clonic (GTC) seizures are dramatic and the best recognized form of seizures. They are commonly referred to as grand mal, but this term is archaic and does not distinguish seizures of focal onset from those with a generalized onset. Generalized tonic-clonic seizures do not have an aura, but they may be preceded by a prodrome—the vague sense a seizure will occur—lasting up to hours. Seizure onset is abrupt, most often with loss of consciousness and a generalized tonic contraction, but some seizures may be initiated with a series of myoclonic jerks, leading to the term clonic-tonic-clonic seizure. The tonic phase may have asymmetrical movements, and these often change from seizure to seizure. One such commonly encountered asymmetry is versive head turning, which is not evidence of a focal onset (Chin and Miller, 2004; Niaz et al., 1999). The tonic phase includes an upward eye deviation with eyes half open and the mouth open. Involvement of the respiratory muscles usually produces a forced expiration that produces a loud guttural vocalization, often referred to as the epileptic cry. Cyanosis may occur during the tonic phase in association with apnea. The tonic phase gradually evolves to clonic activity. The transition can be with initially high-frequency and low-amplitude motion, often referred to as a vibratory phase. With seizure progression, the frequency of clonic jerks decreases, and the amplitude may initially increase but later decreases just before the seizure stops. In the immediate postictal state the individual is limp and unresponsive. Respiration is loud and snoring in character (stertorous). The postictal state is often followed by sleep, although the individual may awaken briefly with postictal confusion. Tongue biting commonly occurs and most often affects the side of the tongue. Incontinence of urine is common, and incontinence of stool may also occur. After awakening, patients often have a pronounced headache and generalized muscle soreness. Generalized tonic-clonic seizures rarely last more than 2 minutes. The severity may vary. The postictal state seems to correlate with severity and duration.

Generalized Atonic Seizures

Generalized atonic are associated with very brief, sudden loss of tone and vary from extremely subtle, manifesting with only a head drop, to generalized loss of tone and falling. Atonic seizures may result in falling if the person is standing, then called a drop attack. However, drop attacks may be the result of both generalized atonic and generalized tonic seizures. There is a very brief loss of consciousness and brief postictal confusion. Seizures are usually very brief, lasting 1 second to a few seconds. They may be preceded by a brief myoclonic jerk, in which case the seizure type is called myoclonic-atonic. Very brief atonic seizures are typical of the syndrome of myoclonic-astatic epilepsy (Doose syndrome) (Oguni et al., 2001). More prolonged atonic seizures can be seen with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or other symptomatic generalized epilepsies. Despite their brief duration, generalized atonic seizures can result in serious injury and are an important cause of morbidity in epilepsy.

Generalized-Onset Seizures with Focal Evolution

Generalized-onset seizures rarely may evolve to focal seizures (Deng et al., 2007; Williamson et al., 2009). This seems to occur with either myoclonic or absence seizures. The clinical manifestations most often are behavioral arrest and staring, with minor automatisms. However, focal motor manifestations may also occur. This type of seizure tends to be prolonged and may be associated with postictal confusion (Williamson et al., 2009).

Classification of Epilepsies and Epileptic Syndromes

The classification of seizures addresses single seizure events and not epilepsy as a condition. The 1989 classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes tried to organize epilepsies and epilepsy syndromes (Commission on Classification and Terminology, 1989). It defined an epileptic syndrome as “an epileptic disorder characterized by a cluster of signs and symptoms customarily occurring together; these include such items as type of seizure, etiology, anatomy, precipitating factors, age of onset, severity, chronicity, diurnal and circadian cycling, and sometimes prognosis.” A syndrome does not necessarily have a common etiology and prognosis. Two important divisions were used in the classification. The first separated epilepsies with generalized-onset seizures, called generalized epilepsies, from epilepsies with partial-onset seizures, referred to as localization-related, partial, or focal epilepsies. The other division separated epilepsies of known etiology (named symptomatic epilepsies) from those of unknown etiology. Epilepsies of unknown etiology were named idiopathic if they were pure epilepsy and “not preceded or occasioned by another condition.” These epilepsies were considered to have no underlying cause other than a possible hereditary predisposition. Thus, they were presumed genetic. The idiopathic epilepsies were also defined by an age-related onset and clinical and EEG characteristics. Epilepsies of unknown etiology were called cryptogenic if they were presumed symptomatic, but with an occult etiology. Although the term cryptogenic remains widely used in the epilepsy field, confusion exists concerning its exact meaning, which has resulted in a recommendation to replace it with the term probably symptomatic (Engel, 2001). The 1989 classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes also subdivided symptomatic partial epilepsies based on lobar anatomical localization of the epileptogenic zone into temporal, frontal, parietal, and occipital lobe epilepsy. Temporal lobe epilepsy was further subdivided into amygdalohippocampal and lateral temporal, and frontal lobe epilepsy into 7 subgroups: supplementary motor, cingulate, anterior frontopolar, orbitofrontal, dorsolateral, opercular, and motor cortex. The abbreviated classification is found in Box 67.2.

The 1989 classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes merits updating because of the recognition of new epileptic syndromes and the discovery of the genetic basis for several known epilepsies. The most recent report of the ILAE commission on classification simplified the classification of epilepsies by eliminating the division of localization-related and generalized epilepsies (Berg et al., 2010). Instead, it suggested a listing of epilepsies by age of onset, distinctive constellations, or underlying cause (Box 67.3). The list incorporated newly identified or characterized epileptic conditions. The report also recommended addressing underlying etiologies with the terms genetic, structural/metabolic, and unknown cause, thus replacing the terms idiopathic, symptomatic, and cryptogenic.

Box 67.3

Electroclinical Syndromes and Other Epilepsies

Electroclinical Syndromes Arranged by Age at Onset

Childhood

Febrile seizures plus (FS+) (can start in infancy)

Epilepsy with myoclonic atonic (previously astatic) seizures

Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS)

Autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy (ADNFLE)

Late-onset childhood occipital epilepsy (Gastaut type)

Epilepsy with myoclonic absences

Epileptic encephalopathy with continuous spike-and-wave during sleep (CSWS)

From Berg, A.T., Berkovic, S.F., Brodie, M.J., et al., 2010. Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology, 2005-2009. Epilepsia 51, 676-685; Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy, 1981. Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia 22, 489-501; Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy, 1989. Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia 30, 389-399.

Epileptic Syndromes

An epileptic syndrome was defined as a complex of signs and syndromes that define a unique epilepsy condition with different etiologies. A syndrome must involve more than just a seizure type (Engel, 2006). One important characteristic of syndromes is the characteristic age at onset. The most recent revision recommended that the term syndrome be restricted to a clinical entity that is reliably identified by a cluster of electroclinical characteristics (Berg et al., 2010). It recommended using the term constellation for epilepsies that do not quite qualify to represent a syndrome; yet there are diagnostically meaningful forms of epilepsy that may have implications for clinical treatment, particularly surgery. The classification of epilepsies in epileptic syndromes published in 1989 divides epilepsies into localization-related (focal, local, partial) and generalized. The basis for that subdivision is that most patients will have either partial-onset seizure types only or generalized-onset seizure types only. However there are syndromes in which both partial and generalized seizure types may coexist in the same individual, or the epilepsy may express itself with generalized seizure types in some individuals and partial seizure types in others. As a result, the 2010 revision recommended dropping the partial-generalized subdivision (Berg et al., 2010). In addition, it recommended using the term genetic for the “idiopathic” epilepsies that were presumed to be genetic in nature. The discussion that follows will briefly describe selected syndromes and constellations following the order suggested by the latest ILAE recommendations (see Box 67.3).

Benign Familial Neonatal Epilepsy

Benign familial neonatal epilepsy was previously referred to as benign familial neonatal convulsions (Plouin and Anderson, 2005). This rare, dominantly inherited disorder is due to mutations affecting voltage-gated potassium channel genes (KCNQ2, KCNQ3) (Biervert and Steinlein, 1999). Affected infants are usually full term and appear normal at birth. In 80% of instances, seizures start on the second or third day of life, although some infants may develop seizures later in the first month of life. The seizures are typically clonic but often preceded by a tonic component. They are more often unilateral but can also be bilateral. The seizures remit within 2 to 6 months. There is a slight increase in the risk of later epilepsy (11%-15%).

Early Myoclonic Encephalopathy and Ohtahara Syndrome

Early myoclonic encephalopathy and Ohtahara syndrome have much in common, including age at onset in the neonatal period, severe seizure manifestations, and an EEG pattern of burst-suppression, in which periods of high-voltage EEG activity are separated by periods of generalized attenuation (Aicardi and Ohtahara, 2005; Djukic et al., 2006; Ohtahara and Yamatogi, 2006).

West Syndrome

West syndrome has a later age at onset, with a peak onset between 3 and 7 months of age. It is characterized by a clinical triad of epileptic spasms, arrest or deterioration of psychomotor development, and a characteristic EEG pattern called hypsarrhythmia (Dulac and Tuxhorn, 2005). The disorder is heterogeneous in its etiology. Epileptic spasms are usually the initial manifestation. They tend to occur in clusters, sometimes multiple times a day. Approximately two-thirds of infants have brain lesions. Psychomotor development may be abnormal prior to onset, but there is a clear deterioration after onset. The spasms may have asymmetries, which are more likely when there is a focal brain lesion. The prognosis is variable, with a small portion of patients recovering quickly without sequelae. This is more likely to happen in the absence of brain pathology. Otherwise, the prognosis is unfavorable, with more than 70% developing mental retardation and other cognitive disabilities. The treatment of infantile spasms has some important differences from treatment of other seizure types. Steroids such as corticotropin (adrenocorticotropic hormone [ACTH]) and prednisone are helpful, particularly in the absence of underlying known pathology.

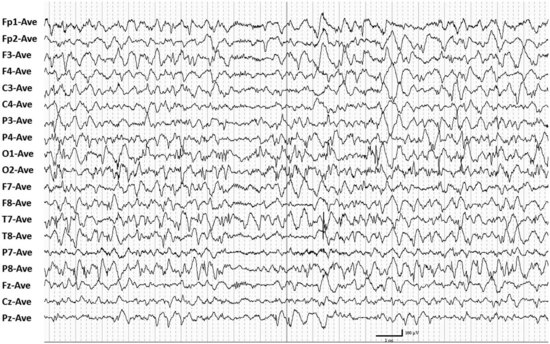

Hypsarrhythmia is characterized by high-voltage disorganized EEG activity with slow waves and multifocal spikes and sharp waves punctuated by periods of generalized attenuation (Fig. 67.2). When a spasm occurs it is usually during a period of attenuation. The attenuation may have superimposed high-frequency, low-voltage EEG activity. The periods of attenuation are typically very short in duration, lasting 1 to 2 seconds.

Dravet Syndrome

Dravet syndrome, also called severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy, is usually due to a de novo mutation affecting the SCN1A gene encoding the α1 sodium channel subunit (Claes et al., 2001). De novo mutations account for about 95% of cases. The typical clinical presentation is that a previously normally developing infant has febrile status epilepticus at around 6 months of age, and then recurrent generalized or shifting hemiclonic seizures are seen, often triggered by fever. After 1 year of age, other seizure types appear, including myoclonic seizures, absence seizures, and complex partial seizures as well as atonic seizures at times. The seizures are drug resistant and may be exacerbated by some sodium channel blockers such as carbamazepine and lamotrigine. A delay or arrest in development may occur, and even regression may be seen, typically after episodes of prolonged seizure activity (Dravet et al., 2005; Scheffer et al., 2009). The prognosis is poor; the majority of individuals develop intellectual disability and at times ataxia and spasticity.

It has now become recognized that Dravet syndrome accounts for a large proportion of individuals previously diagnosed with vaccine encephalopathy (Berkovic et al., 2006). The fever associated with vaccination may cause an earlier age at onset of Dravet syndrome, but it does not affect the eventual course of the condition (McIntosh et al., 2010).

Epilepsy with Febrile Seizures Plus

Epilepsy with febrile seizures plus appears to be autosomal dominant in inheritance, often due to a sodium channel mutation most often in the SCN1A or SCN1B gene (Escayg et al., 2001; Wallace et al., 2002). It can also be due to a mutation in the γ2 subunit of the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-A receptor (Harkin et al., 2002). No mutation has been identified in the majority of families. The condition has a heterogeneous phenotype in affected individuals (Scheffer and Berkovic, 1997; Singh et al., 1999). Some individuals have only the typical febrile seizure phenotype, with febrile seizures disappearing by 6 years of age. Other individuals have febrile seizures plus, which refers to febrile seizures persisting beyond 6 years of age or febrile seizures intermixed with afebrile generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Other individuals even have other seizure types such as generalized absence or myoclonic seizures. Less common seizure types are myoclonic-atonic and partial seizures typical of temporal lobe origin (Abou-Khalil et al., 2001; Scheffer et al., 2007).

Panayiotopoulos Syndrome

The onset of seizures in Panayiotopoulos syndrome is typically between 1 and 14 years of age, with a peak at 4 to 5 years (Covanis et al., 2005). Seizures include autonomic manifestations, particularly ictal vomiting, altered responsiveness and arrest of activity, and deviation of the eyes to one side. Autonomic manifestations are particularly pronounced (Caraballo et al., 2007). Seizures can be very prolonged, lasting longer than 30 minutes, qualifying for complex partial status epilepticus. Seizures predominate during sleep. The EEG shows multifocal spikes but with posterior predominance. Despite the alarming seizure manifestations, prognosis is generally good. Seizures are infrequent, with about a quarter of patients having only one seizure and half having two to five at most. Remission typically occurs within 1 to 3 years of onset.

Epilepsy with Myoclonic Atonic Seizures (Myoclonic Astatic Epilepsy or Doose Syndrome)

This presumed genetic epilepsy is characterized by seizure onset between 18 and 60 months of age (Guerrini et al., 2005). The characteristic seizure types are myoclonic and myoclonic-atonic seizures, present in all affected children. Tonic-clonic seizures are also seen in a majority of children. Atypical absence seizures are also common and frequently associated with reduced muscle tone. Pure atonic seizures may also occur. Tonic seizures are less frequently seen. Generalized tonic-clonic seizures are most often the seizure type that results in the diagnosis of epilepsy, with smaller seizures noticed thereafter. Seizures can be easily precipitated by inappropriate treatment with carbamazepine. The course of the condition is somewhat unpredictable. In more than half of affected children, the seizures go into remission. More than half of patients also have normal cognitive function, with less than half having mild to severe mental retardation. A worse prognosis is predicted by generalized tonic-clonic seizures in the first 2 years of life and early status epilepticus (Kelley and Kossoff, 2010).

Benign Epilepsy with Centrotemporal Spikes

Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS) is also referred to as benign rolandic epilepsy. This is the most common form of idiopathic partial epilepsy in children (Dalla Bernardina et al., 2005). Seizures begin between 3 and 13 years of age, with a peak between 5 and 8 years. Affected children will have had a normal development and normal cognitive function. Seizures typically start with paresthesias affecting one side of the face, particularly around the mouth, then contraction of that side of the face evolving into clonic activity of the face. Increased salivation and drooling occurs. Consciousness is preserved in the vast majority of children if the seizure does not secondarily generalize. Seizures are typically nocturnal and generally have a low rate of recurrence, so treatment is not always necessary. The natural history is characterized by spontaneous remission around the time of puberty. Even though long-term prognosis is excellent, patients with BECTS may have cognitive and behavioral problems while the condition is active.

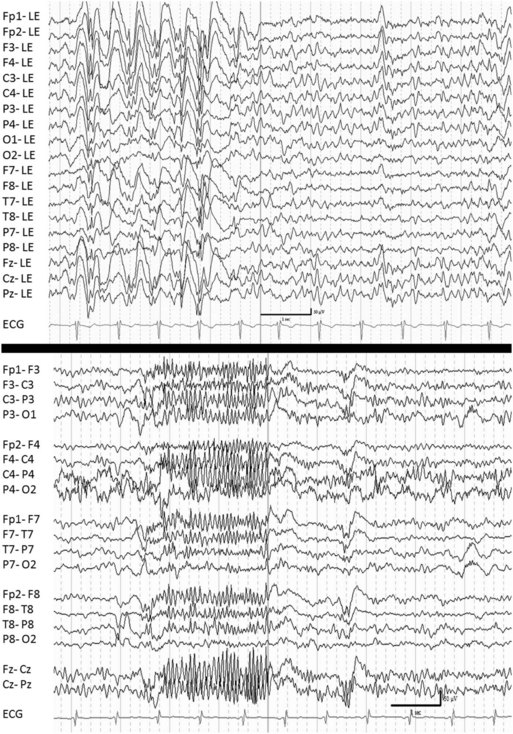

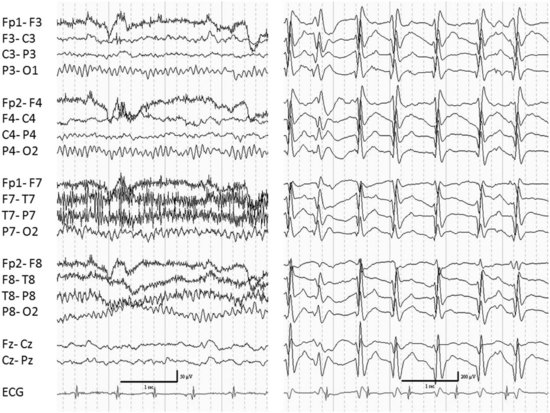

BECTS has long been thought to have a genetic basis, but the concordance in identical twins is low, suggesting that other mechanisms may play a role (Vadlamudi et al., 2004). The diagnosis of BECTS depends on the clinical presentation as well as the EEG. The typical EEG abnormality is high-voltage central-midtemporal blunt sharp waves activated in sleep (Fig. 67.3). These can become bilateral independent in deeper sleep. It is not uncommon to see atypical fields, particularly posterior temporal or parietal. The incidence of generalized spike-and-wave discharges in affected individuals is increased (Beydoun et al., 1992; Drury and Beydoun, 1991).

Autosomal Dominant Nocturnal Frontal Lobe Epilepsy

Age at seizure onset in autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy is highly variable but is most often younger than age 20, with a mean between 8 and 11 years. Seizures typically arise out of sleep. In their most pronounced expression, they may be hypermotor with vigorous frenetic movements of the extremities such as thrashing, kicking, or bicycling. The seizures may be asymmetrical tonic, sometimes with evolving posturing, or may have a mixture of hypermotor and tonic manifestations. The seizures are usually stereotyped. They are typically short in duration, lasting less than 30 seconds. They can be so short as to simply manifest with paroxysmal arousal (Provini et al., 1999). The condition is often misdiagnosed as a sleep disorder or psychogenic seizures (Scheffer et al., 1995).

This disorder is genetically heterogeneous (De Marco et al., 2007) and is typically due to mutations affecting the neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (Steinlein et al., 1995). Carbamazepine appeared particularly effective in this condition. Interestingly, the mutated nicotinic receptors were found to be more sensitive to carbamazepine than to valproate (Picard et al., 1999).

Late-Onset Childhood Occipital Epilepsy (Gastaut type)

The age at onset of seizures in late-onset childhood occipital epilepsy ranges from 3 to 16 years, with a mean age of 8 (Covanis et al., 2005). The seizures are of occipital lobe onset and manifest with visual symptoms. The ictal phenomena include elementary visual hallucinations, complex visual hallucinations and illusions, visual loss in one field or total blindness, eye deviation, and eye blinking. There may be progression of seizure manifestations with spread beyond the occipital lobe, particularly lateralized or generalized tonic-clonic activity. Consciousness is usually preserved if seizure activity does not spread beyond the occipital lobe. Postictal headache is a very common symptom, resulting in confusion with migraine. The interictal EEG is characterized by occipital spikes and sharp waves that can be extremely frequent, and typically activated with eye closure. The discharges can be so frequent as to raise concern for an ictal pattern. The activation with eye closure has been termed fixation-off photosensitivity.

Epilepsy with Myoclonic Absences

Epilepsy with myoclonic absences is a syndrome with male predominance and starts between 1 and 12 years of age, with a mean of 7 years (Bureau and Tassinari, 2005a). Its most distinctive seizure type is myoclonic absences. These seizures include impairment of consciousness of variable degree and very prominent myoclonus involving primarily the upper extremities but also the legs. The duration varies from 10 to 60 seconds, and seizures typically recur several times a day. The associated EEG usually shows 3-Hz generalized rhythmic spike-and-wave activity similar to what is seen in typical absence seizures. Approximately two-thirds of patients also have other seizure types, particularly generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Seizures tend to be resistant to monotherapy and often require dual therapy with valproate and ethosuximide or one of these agents in combination with lamotrigine.

Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome

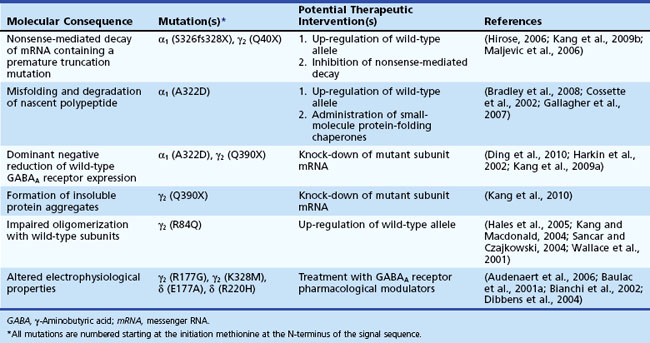

Lennox-Gastaut syndrome is defined by a triad of several seizure types including generalized tonic, generalized atonic, and atypical absence seizures, a characteristic interictal EEG abnormality of generalized slow spike-and-wave discharges (<2.5 Hz) in waking and bursts of paroxysmal fast activity (≈10 Hz) in sleep (Fig. 67.4), and cognitive dysfunction (Arzimanoglou et al., 2009; Beaumanoir and Blume, 2005). Drop attacks due to either generalized atonic or generalized tonic seizures, tend to be the most debilitating seizure type because of associated injuries. The age of onset is between 3 and 10 years with a peak between 3 and 5 years. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome may start de novo or may evolve, for example from West syndrome. Seizures tend to be drug-resistant. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome tends to be a chronic disorder even though epilepsy may become less active over time. Almost half of these patients may appear normal before onset of seizures, but deterioration occurs, and the cause is probably multifactorial.

Epileptic Encephalopathy with Continuous Spike-and-Wave During Sleep and Landau Kleffner Syndrome

The common features of the related conditions of epileptic encephalopathy with continuous spike-and-wave during sleep (CSWS) and Landau Kleffner syndrome (LKS) are a decline in cognitive function in association with an EEG pattern of continuous spike-and-wave activity during slow wave sleep (Fig. 67.5). In both conditions the associated seizures are often easy to control, and the predominant clinical manifestations are related to the EEG abnormality in sleep (Nickels and Wirrell, 2008; Tassinari et al., 2005).

In the case of LKS, the cognitive decline is specifically in the area of speech. The condition is often called acquired epileptic aphasia. This disorder typically appears between 2 and 8 years of age, with a peak between 5 and 7 years. The most common initial manifestation is verbal auditory agnosia. The language disturbance will usually progress despite good control of clinical seizures. In fact, clinical seizures may not even occur in about a quarter of patients. The evolution is variable. Spontaneous remissions may occur within the first year. Classical antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) may be ineffective. Benefits have been reported with valproate, levetiracetam, and benzodiazepines which reduce the EEG abnormality. Steroids and immunoglobulins have been reported to be helpful. Surgical treatment with multiple subpial transections has been advocated (Morrell et al., 1995).

Childhood Absence Epilepsy

CAE syndrome, previously referred to as petit mal or pyknolepsy, typically starts between the ages of 4 and 10 years with a peak between 5 and 7 years (Hirsch and Panayiotopoulos, 2005). Affected children are normal in their development and neurological status. The key seizure type is generalized typical absence seizures occurring many times a day. In association with seizures, the EEG shows generalized synchronous and symmetrical spike-and-wave activity with a frequency around 3 Hz. It is not unusual for the spike-and-wave frequency to be initially faster (up to 4 Hz) and drop by approximately 0.5 to 1 Hz by the end of the ictal discharge. Seizure duration is brief, usually less than 15 seconds. Seizure frequency is very high, with multiple daily seizures. In 2005 the ILAE proposed strict criteria to define the syndrome, which include the absence of generalized tonic-clonic or myoclonic seizures prior to or during the active stage of absence seizures. The criteria also exclude eyelid and perioral myoclonia, high-amplitude rhythmic jerking of the limbs, and arrhythmic jerks of the head, trunk, or limbs (Loiseau and Panayiotopoulos, 2005). With this strict definition of the syndrome, many patients with a predominance of absence seizures are excluded and cannot be classified as having CAE (Ma et al., 2010; Valentin et al., 2007), but a very favorable prognosis is expected. Only 8% of patients fulfilling the strict criteria had generalized tonic-clonic seizures, compared to 30% of those who did not (Grosso et al., 2005), and 65% of those satisfying the stricter criteria had a complete seizure remission, compared to 23% of those who did not. Persistence or relapse of seizures tends to be predominately related to generalized tonic-clonic seizures. In some instances, CAE evolves into JME in the second decade. This will be discussed later under that heading.

CAE is thought to be genetically determined, with high concordance for monozygotic twins (Berkovic et al., 1998). However, the exact mode of inheritance is unknown. Although some families had a single gene mutation (including calcium channel mutations), most are thought to have polygenic inheritance (Hughes, 2009).

For children with pure absence seizures, ethosuximide is the treatment of choice (Glauser et al., 2010). Coexistence of other seizure types requires a wider-spectrum AED.

Juvenile Absence Epilepsy

Juvenile absence epilepsy is very similar to CAE except that the age at onset is in the second decade, with a peak between age 10 and 12 (Wolf and Inoue, 2005). The absence seizures are not as frequent as in CAE. In addition, the majority of patients also have generalized tonic-clonic seizures. This condition has a greater tendency for persistence of seizures into adulthood than is the case with CAE.

Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME), also known as juvenile myoclonic epilepsy of Janz or impulsive petit mal, is common (Thomas et al., 2005) and accounts for up to 10% of all cases of epilepsy. The age at onset is typically between 12 and 18, but epilepsy may start in the first decade in a subgroup of patients who appear to have CAE early on. The defining seizure type is generalized myoclonic seizures, which occur in all patients by definition. Generalized myoclonic seizures typically occur after awakening, particularly with sleep deprivation. They are typically mild, predominately affecting the upper extremities. Although they are the first seizure type to appear, they are often not recognized as seizures and not brought to medical attention. Patients typically come to medical attention after a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, which is most likely to occur after sleep deprivation or binge drinking of alcohol. The physician has to ask about myoclonus in order to make the diagnosis. Approximately one-third of patients also have generalized absence seizures. JME is clinically and genetically heterogeneous (Martinez-Juarez et al., 2006). The most important group is classic JME, and the second largest is CAE evolving to JME. The latter tends to be more treatment resistant.

The diagnosis of the condition is based on the clinical history and EEG, which shows generalized irregular 4- to 6-Hz spike-and-wave activity occurring in bursts. The EEG is most likely to record discharges after awakening (Labate et al., 2007). JME is a lifelong condition. Even though the majority of patients can have seizure remission with medication therapy, more than 90% have a recurrence of seizures upon stopping AEDs. The prognosis for seizure freedom is lowest in individuals with CAE leading to JME and in individuals who have all three seizure types: generalized myoclonic, generalized tonic-clonic, and generalized absence seizures (Gelisse et al., 2001; Martinez-Juarez et al., 2006). Valproate appears to be the most effective medication for all three seizure types, but its teratogenicity and some adverse effects limit its use in women of childbearing age (Montouris and Abou-Khalil, 2009). Seizures may be aggravated by several AEDs that are specific for partial epilepsy (Gelisse et al., 2004; Genton et al., 2000).

JME is thought to have predominantly polygenic inheritance, but there have also been families with autosomal dominant inheritance and several identified mutations (Delgado-Escueta, 2007), including a mutation of the GABAA receptor (Cossette et al., 2002).

Autosomal Dominant Epilepsy with Auditory Features

Autosomal dominant epilepsy with auditory features (ADEAF) is related to a mutation in the leucine-rich glioma-inactivated-1 (LGI1) gene (Ottman et al., 2004). Inheritance, as the name indicates, is autosomal dominant. Seizures typically begin in adolescence or adulthood, with a mean age at onset of 24. Affected subjects commonly report an elementary auditory aura such as buzzing, ringing, humming, or even loss of hearing. Seizures may start with aphasic manifestations when the onset is in the dominant lateral temporal lobe (Gu et al., 2002).

Familial Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

Familial MTLE is a heterogeneous condition. There is a benign syndrome, first identified in twins, in which the most prominent aura is déjà vu with frequent simple partial seizures, infrequent complex partial seizures, and rare secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures (Berkovic et al., 1996). Prior febrile seizures are uncommon, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is normal with no hippocampal sclerosis. The epilepsy is frequently not recognized when the only seizure type is subjective simple partial seizures, but when recognized is very responsive to medical therapy.

Other familial MTLE may be associated with prior febrile convulsions, hippocampal sclerosis on MRI, and less responsiveness to medical therapy, at times requiring surgical treatment (Cendes et al., 1998).

Familial MTLE is most probably polygenic in inheritance, even though there are reports of autosomal dominant inheritance (Crompton et al., 2010). No gene mutation has yet been identified.

Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy with Hippocampal Sclerosis

MTLE with hippocampal sclerosis is classified as a distinctive constellation rather than a syndrome (Berg et al., 2010). Mesial temporal or hippocampal sclerosis is the most common pathology noted in surgical specimens from patients undergoing temporal lobectomy for drug-resistant temporal lobe seizures. It is characterized by neuronal loss and gliosis predominately affecting CA1 and CA3 sectors of the hippocampus, with relative sparing of CA2. Patients with MTLE and hippocampal sclerosis frequently have a history of antecedent febrile seizures (up to 80%) (French et al., 1993). The febrile seizures are usually complex, in particular prolonged. Even though febrile status epilepticus is known to injure the hippocampus in some instances, it is not clear that this is the only factor at play (VanLandingham et al., 1998). Some studies have shown evidence of prior hippocampal malformation that may predispose to injury (Fernandez et al., 1998; Park et al., 2010a). In addition, hippocampal sclerosis has been reported in familial MTLE without prior febrile seizures (Kobayashi et al., 2003). The age at onset of habitual afebrile seizures is variable but most commonly is in late childhood or adolescence. The presence of hippocampal sclerosis predicts poor response to medical therapy (Semah et al., 1998). However, the exact percentage of individuals who are drug resistant has varied between studies. It is not unusual for seizures to be drug responsive initially, with long remissions but later evolution to drug resistance (Berg et al., 2006).

The seizure pattern has already been described. The clinical seizure characteristics cannot reliably distinguish MTLE due to hippocampal sclerosis from that due to lesions (Wieser, 2004).

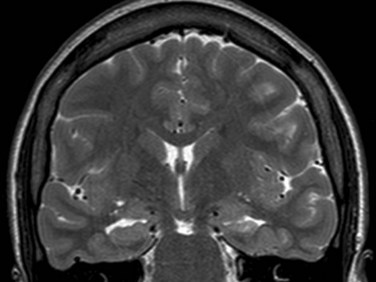

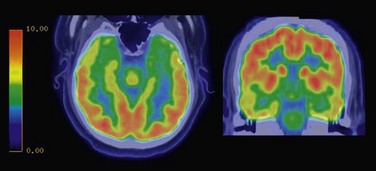

The hippocampal sclerosis is usually identified on MRI showing decreased volume and increased signal in the affected hippocampus (Fig. 67.6). Positron emission tomography (PET) usually shows temporal hypometabolism that is predominant in the mesial temporal region on the affected side (Fig. 67.7).

While drug resistance is common, the response rate for surgical therapy is excellent. After temporal lobectomy or selective amgydalohippocampectomy, 60% to 80% of individuals are seizure free (Wieser, 2004).

Rasmussen Syndrome

Rasmussen syndrome is a chronic progressive disorder of unknown etiology, and probably heterogeneous (Hart and Andermann, 2005). Seizures most commonly start between 1 and 14 years of age with focal-onset motor seizures. The seizures can remain simple partial or evolve to complex partial or secondary generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Seizures usually start in the same hemisphere. They become progressively more frequent with episodes of status epilepticus. Progressive hemiparesis and other deficits occur, depending on the affected hemisphere. General intellectual decline occurs at the time of hemiparesis. Imaging shows progressive hemiatrophy, with lesser atrophy on the other side. An abnormal increased T2 signal is initially most pronounced in the perisylvian region. PET reveals marked decreased metabolism in the affected hemisphere.

An autoimmune etiology is suspected. In some patients, antibodies to the GluR3 subunit of the glutamate receptor have been identified (Rogers et al., 1994). Some benefit may occur with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), plasmapheresis, and corticosteroids, but hemispherectomy is generally required to achieve seizure control.

Progressive Myoclonus Epilepsies

Progressive myoclonus epilepsies (PME) are a heterogeneous group of genetic disorders characterized by myoclonus, generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and progressive neurological dysfunction, predominately with cerebellar ataxia and often with dementia (Genton et al., 2005). Included in the group are Unverricht-Lundborg disease, Lafora body disease, mitochondrial encephalopathy with ragged red fibers, and ceroid lipofuscinosis, among others. Unverricht-Lundborg disease was also called Baltic myoclonus, but it is recognized now as a worldwide condition. It is due to a mutation in the cystatin B gene (Genton, 2010). The onset is typically between 7 and 16 years of age, initially with action myoclonus then later development of tonic-clonic or clonic-tonic-clonic seizures. The myoclonus worsens progressively and greatly limits motor function. Ataxia occurs and is generally mild, but it can be very aggravated by the use of phenytoin. Phenytoin can also cause mild dementia.

Gelastic Seizures with Hypothalamic Hamartoma

Gelastic seizures with hypothalamic hamartoma typically starts with gelastic seizures in early life, with other seizures also becoming associated later on (Berkovic et al., 2003). There may be cognitive and behavioral disturbances. Some individuals have precocious puberty and a short stature. MRI reveals a hypothalamic hamartoma that can vary in size and appearance. Seizures originate within the hamartoma.

Febrile Seizures

Febrile seizures are not traditionally diagnosed as a form of epilepsy per se, even though the condition is characterized by epileptic seizures (Berg et al., 2010). The condition affects 2% to 5% of children, mostly between 3 months and 6 years of age. It is the most common form of seizures in children (Knudsen, 2000) and a benign disorder in the vast majority of those affected. Most febrile seizures are generalized tonic-clonic in semiology. They are typically symmetrical, last less than 15 minutes, and usually only one seizure occurs in association with a particular illness. Febrile seizures that satisfy the above criteria are called simple febrile seizures. Complex febrile seizures are defined by one or more of the following three criteria: prolonged duration of greater than 15 minutes, focal features (either focal ictal features or lateralized postictal weakness), or the occurrence of more than one seizure in 24 hours or with the same febrile illness. Most affected children will not have a recurrence of a febrile seizure in their lifetime. Approximately 30% to 40% will have at least one recurrence, but multiple recurrences are infrequent. Predictors of recurrence are early age at onset (<1 year), the presence of epilepsy or febrile seizures in first-degree relatives, and attendance at daycare, which increases the risk of febrile infectious illnesses.

Even though febrile seizures are a benign condition and the vast majority of affected children never develop afebrile seizures, they do increase the risk of later epilepsy. In one important study, the risk of later epilepsy was 7% by age 25 years (Annegers et al., 1987). In another study of children seen in the emergency room for their first febrile seizure, the risk of afebrile seizures was 6% at 2 years (Berg and Shinnar, 1996). The factors that predict later epilepsy include preexisting neurodevelopmental abnormalities, complex features (prolonged duration, focal features, and multiple occurrences per day), a family history of epilepsy, and recurrent febrile seizures. The presence of one complex feature increases the risk to 6% to 8%, two complex features, 17% to 22%, and all three complex features, 49% (Annegers et al., 1987). Complex features tend to predict an increased risk of partial epilepsy, while a large number of febrile seizures and a positive family history of epilepsy increase the risk of later generalized epilepsy.

Single febrile seizures are more likely to be polygenic, whereas families with single-gene inheritance are more likely to include recurrent febrile seizures. Digenic inheritance has been described (Baulac et al., 2001b). Affected individuals had two mutations, and those unaffected had either one or no mutation.

Since most febrile seizures are benign, there is usually no need to treat affected patients with prophylactic daily medication. Intermittent medication may be given at the time of fever. For example, diazepam may be given orally or rectally in patients with frequent recurrent febrile seizures. Rectal diazepam can be administered for prolonged febrile seizures (Knudsen, 2000).

Causes and Risk Factors

Infections are an important risk factor for epilepsy. The risk of later epilepsy is higher for both meningitis and encephalitis if seizures occur during the acute illness. The relative risk of later epilepsy was increased 16-fold after encephalitis and 4-fold after bacterial meningitis (Annegers et al., 1988). The risk of later epilepsy was greatest with infection prior to age 5. Early occurrence of meningitis or encephalitis prior to age 4 predicted mesial temporal localization with hippocampal sclerosis, and better outcome with temporal lobectomy (O’Brien et al., 2002).

Head Trauma

Head trauma is an important risk factor for epilepsy, with the greatest risk seen in association with penetrating head injury, head injury with depressed skull fracture, and severe head trauma with prolonged loss of consciousness. In a landmark study, mild traumatic brain injury (characterized by absence of fracture and a loss of consciousness or posttraumatic amnesia for less than 30 minutes) was associated with only a 1.5-fold increase in risk of epilepsy, which was not statistically significant (Annegers et al., 1998). Patients with moderate head injury, defined as loss of consciousness or posttraumatic amnesia for 30 minutes to 24 hours or a skull fracture, had a 2.9-fold increase in risk, while those with severe head injury, including brain contusion or intracranial hematoma or loss of consciousness or posttraumatic amnesia for more than 24 hours, had a 17-fold increased risk. The risk was highest in the first year after the injury but remained increased thereafter for a duration that varied with severity of the injury. For those with moderate brain injuries, the risk was markedly increased for up to 10 years only; for those with severe traumatic brain injury, the risk did not decrease. The Vietnam Head Injury Study (VHIS), in which 92% of subjects had penetrating head injuries, found a 53% prevalence of posttraumatic epilepsy approximately 15 years after the injury. The risk was 580 times higher than that of the general age-matched population in the first year after injury, and it was still 25 times higher after 10 years (Salazar et al., 1985). A more recent follow-up study in a subgroup of the original patients found that 12.6% of individuals who had posttraumatic epilepsy developed epilepsy more than 15 years after the injury (Raymont et al., 2010). Early seizures appeared to be a strong risk factor for late seizures, but early seizures were usually related to the severity of the head injury and intracranial lesions.

Changes in the brain reflecting the process of epileptogenesis are likely in the latent period between the head injury and onset of chronic epilepsy. Among several therapeutic measures tested for efficacy in preventing epilepsy after head injury, none have proven effective (Temkin, 2009). However, phenytoin was effective in preventing seizures in the first week (Temkin et al., 1990). The new AEDs have not been tested for the prevention of posttraumatic epilepsy.

Vascular Malformations

The two vascular malformations most commonly associated with epilepsy are arteriovenous malformations and cavernous malformations. Venous malformations, also called venous anomalies, may be accidental findings not directly related to epilepsy unless associated with a cavernous malformation. Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are high-pressure vascular malformations with arteriovenous shunting. They are a tangle of feeding arteries and draining veins without intervening capillary bed. They may come to attention during evaluation for seizures or after they bleed; they may also be incidental when imaging is performed for unrelated reasons. Because of the high pressure, they are susceptible to bleed at a rate of 1% to 3% per year, which is the main reason they require therapy. Surgical treatment is effective, with one series reporting 94% of patients seizure free, most on no AEDs (Piepgras et al., 1993). Patients with small AVMs were more likely to present with hemorrhage, whereas those with large AVMs were more likely to present with seizures. The best seizure outcome was seen with resection of small AVMs. Endovascular treatment with embolization and radiosurgery can also improve seizure control, though to a lesser extent. Stereotactic radiosurgery rendered more than 50% of patients seizure free and was more likely to be successful when the preoperative seizure frequency was low and the AVM was small (Schauble et al., 2004).

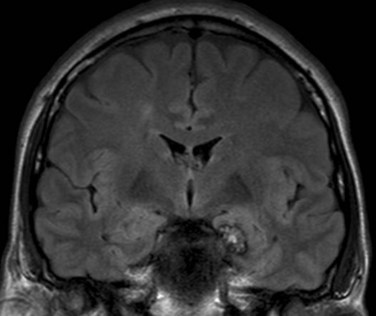

Cavernous malformations consist of blood-filled epithelium-lined caverns with no discrete arteries or veins (Kraemer and Awad, 1994). On MRI they have a characteristic “popcorn” appearance with mixed signal within the lesion and a rim of decreased signal, reflecting hemosiderin (Fig. 67.8). They may be multiple in approximately a third of cases. Cavernous malformations are low-pressure lesions with a much smaller risk of bleeding than AVMs. They are strongly associated with epilepsy. If seizures are controlled with medical therapy, there is no clear indication for surgical resection. However, when epilepsy is drug resistant, resection of the cavernous malformation is associated with excellent results, provided the hemosiderin-stained brain tissue surrounding it is removed (Awad and Jabbour, 2006). Intraoperative monitoring with electrocorticography can also improve surgical outcome (Van Gompel et al., 2009).

Brain Tumors

Brain tumors are a common cause of epilepsy, particularly drug-resistant epilepsy. Most drug-resistant epilepsy occurs with low-grade tumors, particularly those in the temporal lobe (Rajneesh and Binder, 2009). Benign tumors associated with epilepsy are gangliogliomas, dysembryoblastic neuroepithelial tumors (DNET), and low grade gliomas. Excellent seizure control most often occurs after removal of gangliogliomas and DNET tumors. As expected, incomplete resection is associated with less likelihood of seizure control.

Seizures contribute to the morbidity of malignant brain tumors in approximately a quarter of patients. Grade 3 anaplastic astrocytomas are more likely to present with seizures at onset than glioblastoma multiforme (Moots et al., 1995).

Parasitic Infections

Neurocysticercosis is thought to be the leading cause of acquired epilepsy in adulthood in the developing world, but it is an uncommon cause of epilepsy in developed countries. Seizures are thought to occur in 70% to 90% of patients (Pal et al., 2000). Seizures in most patients can be controlled with AEDs. When epilepsy is drug resistant, patients with living cysticerci in the brain can benefit from albendazole, an antiparasitic treatment, in combination with dexamethasone (Garcia et al., 2004).

Stroke

Stroke increases the risk of seizures and epilepsy at any age, but it is the most common cause of seizures in the elderly (Menon and Shorvon, 2009). As in posttraumatic seizures, early seizures that occur within 2 weeks of the stroke most often do not progress to chronic epilepsy, but they do increase the risk of chronic epilepsy. As with head trauma, the risk of chronic epilepsy is highest in the first year after stroke, with a 17-fold increase in the risk compared to population in the community. Compared to individuals who did not have early seizures, approximately 30% of individuals who have early post-stroke seizures develop later epilepsy. This is a 16-fold increase in risk. Seizures and even status epilepticus can be a presenting symptom of acute stroke. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus is difficult to detect.

Inflammatory and Autoimmune Disorders

Immune disorders increase the risk of epilepsy and seizures. In systemic lupus erythematosus, the risk of seizures is 12% to 20% and is more likely with anticardiolipin and anti-Smith antibodies (Najjar et al., 2008). The risk of epilepsy is also increased in primary CNS inflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis. Between 2% and 6% of patients with multiple sclerosis have seizures. Those who do tend to have more extensive cortical involvement with inflammatory disease. Seizures are more likely to occur in the context of acute relapse, but some patients develop chronic epilepsy. Seizures are a more common acute manifestation of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, noted in approximately 50% of patients. However, chronic epilepsy is much less likely, with only about 5% affected.

Hashimoto encephalopathy is a steroid-responsive encephalopathy usually presenting with behavioral-cognitive abnormalities. Seizures occur in 60% of individuals. Patients have elevated antithyroid antibodies, but it is not clear that these antibodies are responsible for the clinical manifestations (Castillo et al., 2006).

Limbic encephalitis is an increasingly recognized cause of epilepsy. Suggested diagnostic criteria include one of disturbance of episodic memory, temporal lobe seizures, or affective disturbance plus the presence of either well-characterized antibodies or unexplained increased signal in the mesial temporal structures, or histopathology of mesial temporal encephalitis (Bien et al., 2007). It can be paraneoplastic or non-paraneoplastic. Neoplastic cases are associated with small cell lung cancer, testicular cancer, thymoma, breast cancer, or teratoma. The most commonly noted antibodies seen in non-paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis include anti–N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antibodies, anti–potassium channel antibodies, and anti–glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibodies (Dalmau et al., 2008; Malter et al., 2010). Immunosuppressive therapies may be effective, particularly in anti–potassium channel antibody limbic encephalitis (Malter et al., 2010). An immune basis of epilepsy should be suspected in individuals who have other autoimmune disease, abrupt or recent onset of seizures (particularly if resistant to AEDs and progressive in frequency and severity), associated manifestations such as behavioral changes and psychosis, severe memory disturbances, and abnormal signal on MRI in the hippocampi.

Other Risk Factors