Chapter 3 Epidural Malignant Tumors

LYMPHOMA

EPIDEMIOLOGY

DISTRIBUTION

There are no reported segmental differences in the occurrence of lymphomas in the spine.

HISTOLOGY/GRADING

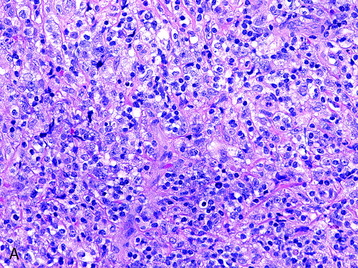

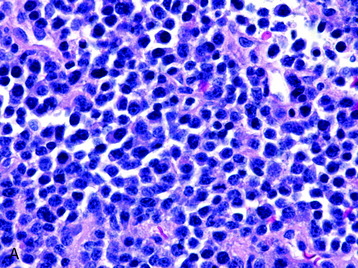

• The vast majority of primary central nervous system lymphomas are diffuse, large B-cell lymphomas; although rare, primary T-cell and Hodgkin’s lymphomas have been reported.1

• The spine is a potential site of involvement by the full spectrum of lymphomas described exhaustively elsewhere.

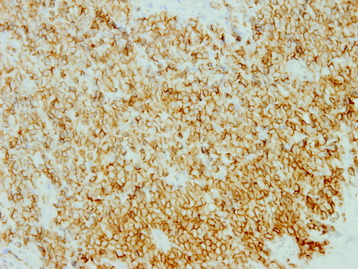

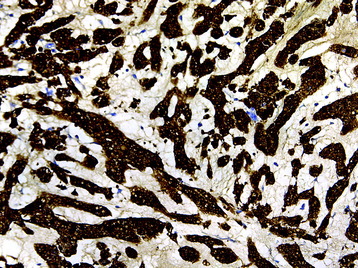

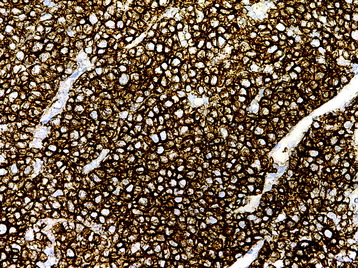

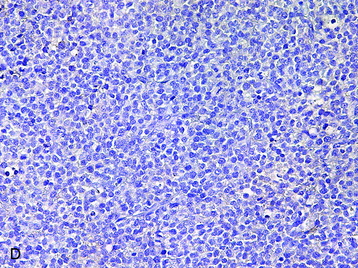

• The diagnosis rests with the identification of a clonal population through the use of immunohistochemical staining or flow cytometric analysis (Figs. 3-1 and 3-2).

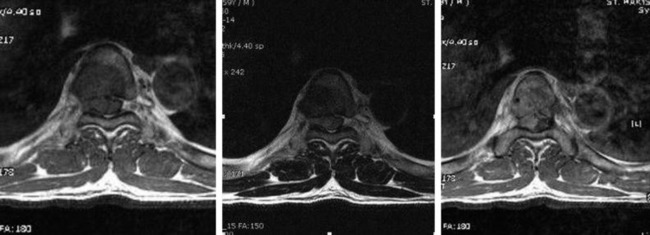

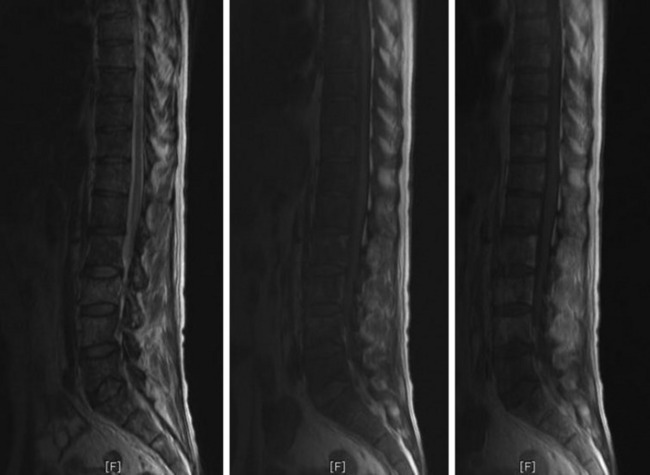

RADIOLOGY

• Lymphoma can show osseous involvement, epidural mass with or without vertebral involvement, leptomeningitic mass, and intramedullary lesions.

OSTEOSARCOMA

EPIDEMIOLOGY

• In the largest series of primary vertebral osteosarcomas reported,2 the median age of the 198 patients was 34 years, and there were slightly more females than males.

HISTOLOGY/GRADING

• Osteosarcomas are high-grade spindle cell neoplasms that form osteoid (Fig. 3-6) and often have associated giant cells.

• Conventional osteosarcomas are subtyped based on the nature of the matrix (e.g., osteoblastic, fibroblastic, chondroblastic) (Figs. 3-7 and 3-8).

RADIOLOGY

• They show cortical destruction and soft tissue mass formation. Bone matrix produced by the malignant cells can be seen on simple radiographs in most cases (Fig. 3-9).

• For MR findings, the mineralized portion of the tumor mass is seen as low signal on T1WI and T2WI. Soft portion of the tumor mass is seen as low signal on T1WI and high on T2WI (Fig. 3-10). With contrast, the mass shows a moderate enhancement pattern.

EWING SARCOMA

EPIDEMIOLOGY

• Primary vertebral Ewing sarcoma is unusual and accounts for slightly less than 10% of all cases of this neoplasm.

• In the largest published series of primary vertebral Ewing sarcoma,3 the average patient age was 19 years and there was a definite male predominance (62%).

DISTRIBUTION

HISTOLOGY/GRADING

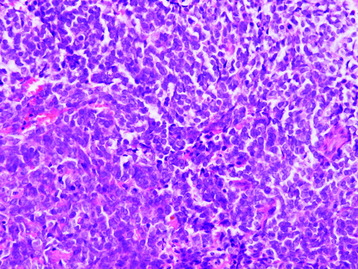

• Ewing sarcoma is one of the “small round blue cell” tumors (Fig. 3-11). The histologic differential is broad, but can usually be clarified through the use of immunohistochemical stains. This differential diagnosis includes, but is not limited to:

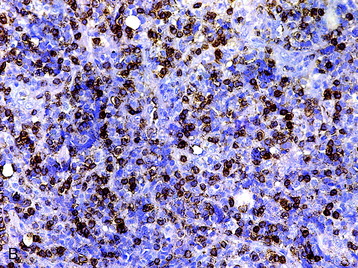

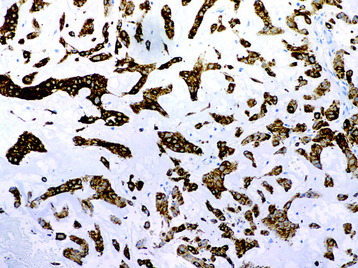

• Ewing sarcoma demonstrates a honeycomb pattern of membranous CD99 immunoreactivity (Fig. 3-12). Definite diagnosis, however, requires cytogenetic or molecular genetic studies for the +(11; 22)(q24; q12) translocation, which is found in more than 95% of cases.5

RADIOLOGY

• This tumor shows a moth-eaten bone destruction pattern. It usually starts from the vertebral body or sacrum.

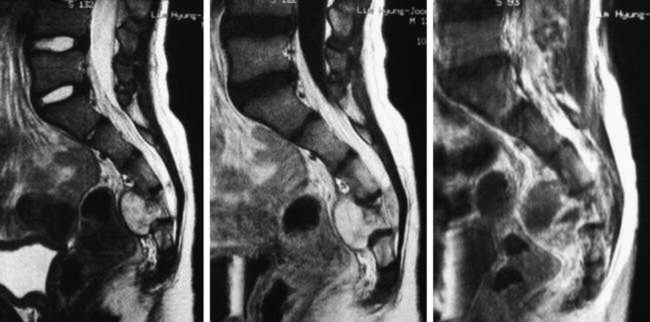

• The vertebral body destruction pattern is not extensive, so tiny perforation of the bony cortex is more common rather than wide loss of the cortical bone. Extraosseous soft tissue mass is often accompanied with the vertebral body mass (Fig. 3-13).

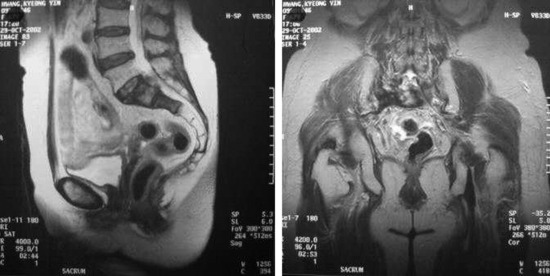

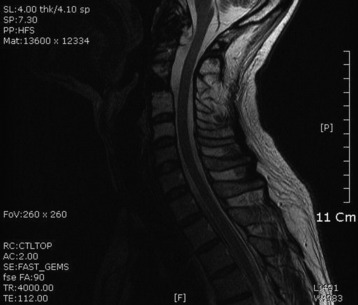

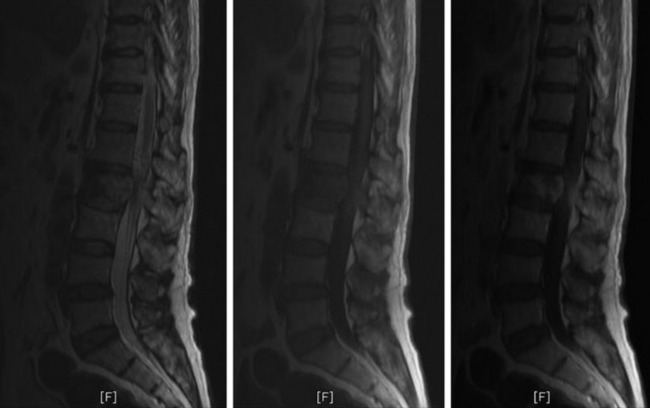

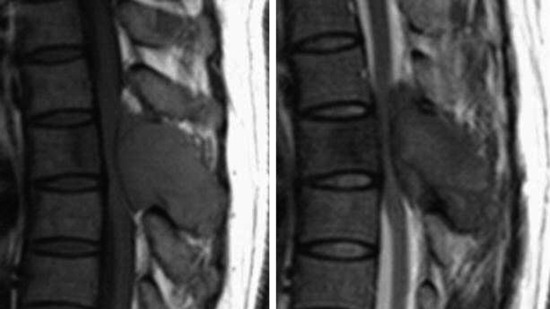

• The signal change in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is variable. On T1WI, the signal is intermediate to low, and on T2WI an intermediate to high signal change is a usual finding (Fig. 3-14). A moderate enhancement pattern is common. A necrotic area is commonly seen in the tumor mass.

CHONDROSARCOMA

EPIDEMIOLOGY

• Primary chondrosarcomas of the mobile spine are rare lesions. Two reviews6,7 document 22 and 21 patients for the two institutions (Istituto Rizzoli and University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center) in 59 and 43 years, respectively.

HISTOLOGY/GRADING

• Grade I chondrosarcomas are mild to moderately cellular neoplasms composed of neoplastic chondrocytes within lacunae in a chondroid matrix (Fig. 3-15).

• With increasing grade, there is greater nuclear atypia and cellularity and often necrosis. If there is a coexistent spindled morphologic pattern, a diagnosis of another more highly malignant tumor (e.g., dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma) is likely.2

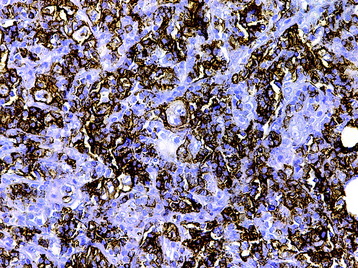

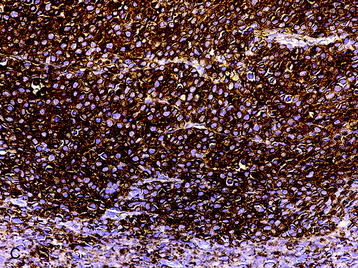

• The histologic differential of low-grade chondrosarcomas includes chordoma. Even though the growth patterns of these two lesions are often evident with sufficient sampling, immunohistochemical staining also can differentiate the lesions; chondrosarcomas demonstrate immunoreactivity for S100 protein (Fig. 3-16) but not keratin (Fig. 3-17), whereas chordomas are immunoreactive for both.

RADIOLOGY

• Chondrosarcoma is a malignant tumor of connective tissue characterized by formation of cartilage matrix by tumor cells.

• This tumor is composed of two parts: chondroid matrix mineralization of ring and arcs and a non-mineralized portion of hyaline cartilage.

• T2WI MR: High signal area of hyaline cartilage and low signal area of mineralization part (Fig. 3-18).

CHORDOMA

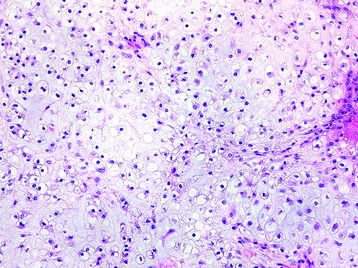

HISTOLOGY/GRADING

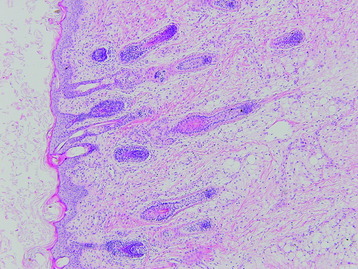

• The tumors are composed of physaliferous (“bubbly”) cells arranged in cords or small clusters within a myxoid matrix (Fig. 3-21).

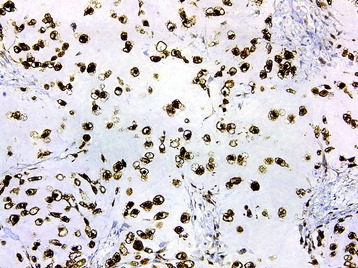

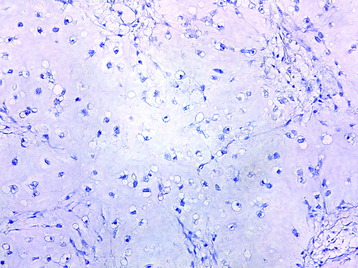

• The primary histologic differential is chondrosarcoma. Chordomas can be distinguished by uniform, strong S100 protein (Fig. 3-22) and keratin (Fig. 3-23) immunoreactivity. Chondrosarcomas demonstrate S100 immunoreactivity only.

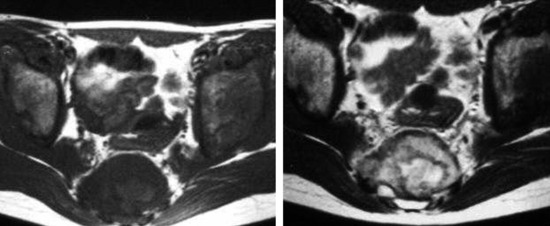

RADIOLOGY

• On T2WI MR, high signal change is as usual. However, in some cases, low signal change can be seen if the tumor mass is rich in fibrous component (Fig. 3-24).

• On T1WI MR, either hypo-signal or iso-signal change is possible (Fig. 3-25). With gadolinium (Gd) use, the enhancement pattern is variable (Figs. 3-26 and 3-27).

SACROCOCCYGEAL TERATOMA

EPIDEMIOLOGY

• Sacrococcygeal teratomas (SCTs) are identified in approximately 1 in 35,000 live births and represent the most common extragonadal germ cell tumor in neonates and young children.9

• In two large studies9,10 composed of 126 and 51 patients, females accounted for 74% and 80% of the study populations, respectively.

DISTRIBUTION

MALIGNANT FIBROUS HISTIOCYTOMA

EPIDEMIOLOGY

• Malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) occurs preponderantly in soft tissues but also occasionally in bone. It is now established that MFH represents a rare primary spinal tumor.

• It is not clear whether this tumor represents a homogeneous entity or a collection of sarcomas of diverse type. It has been suggested that MFH arises from primitive mesenchymal cells capable of multidirectional differentiation.14 Four histologic subtypes of MFH have been described. The most common is the storiform-pleomorphic MFH.

DISTRIBUTION

The vast majority of osseous MFHs occur in long bones, with the femur, tibia, and humerus accounting for approximately 75% of all cases.15

HISTOLOGY

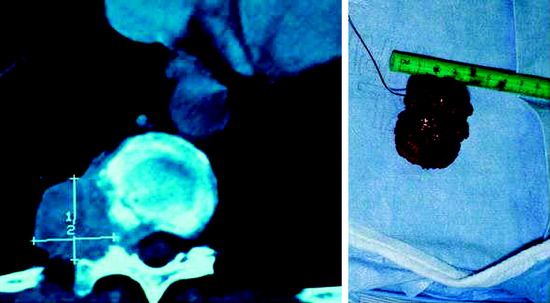

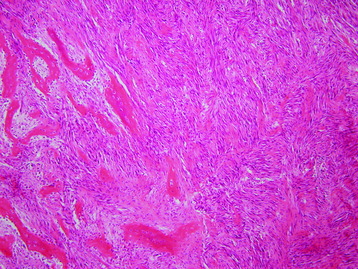

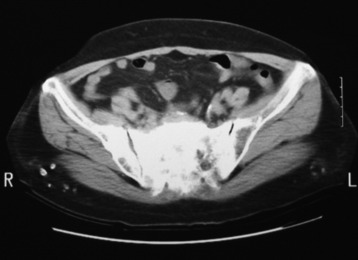

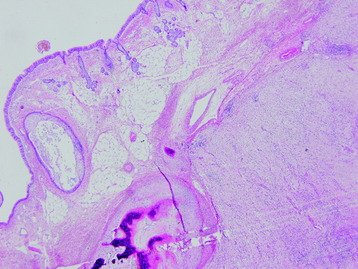

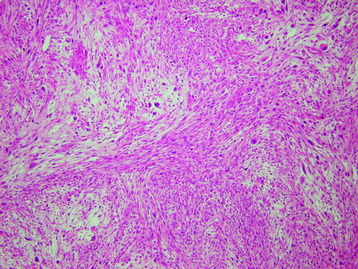

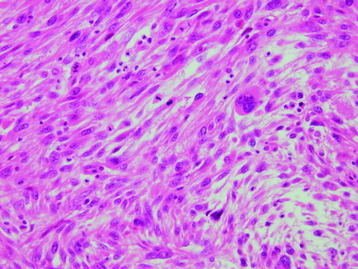

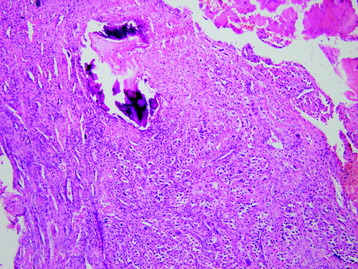

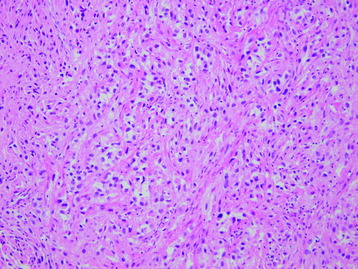

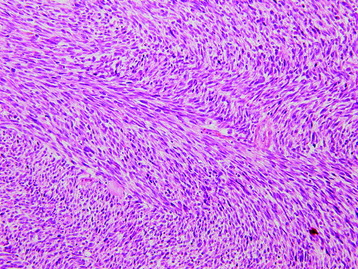

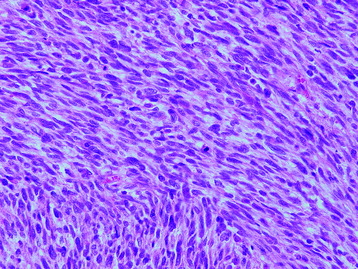

• MFH is a pleomorphic tumor that is primarily composed of pleomorphic mesenchymal cells and shows storiform arrangement (Fig. 3-30).

• The pleomorphic mesenchymal cells are composed of atypical giant cells and fibroblastic cells with frequent mitosis (Fig. 3-31).

RADIOLOGY

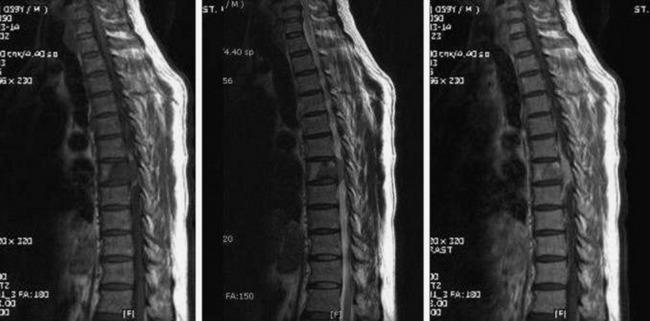

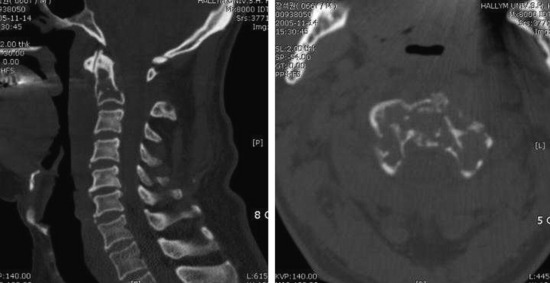

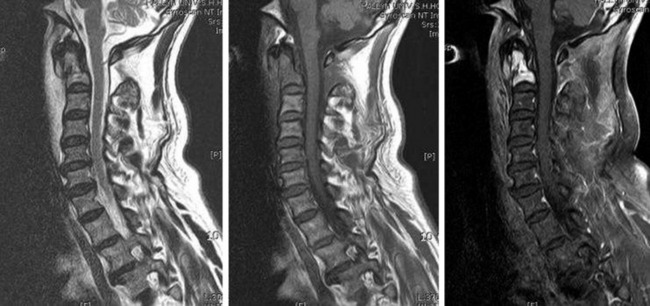

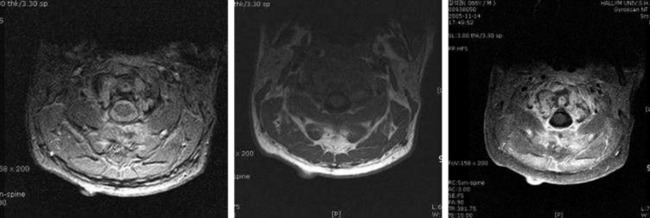

• The plain radiographic and CT findings in osseous MFH include aggressive signs such as lysis and a permeative or moth-eaten pattern.

• Because of involvement of contiguous vertebral bodies and discs, tuberculous spondylitis should be differentially diagnosed.

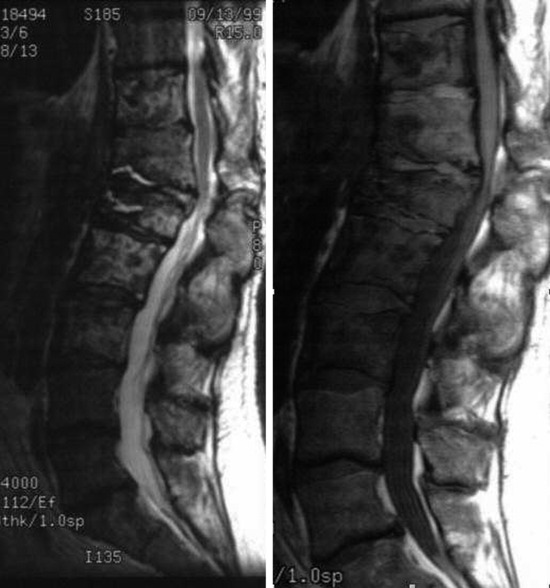

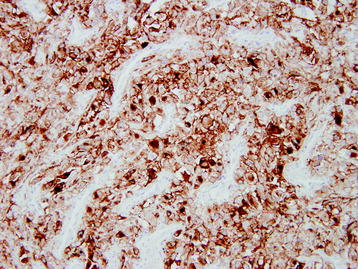

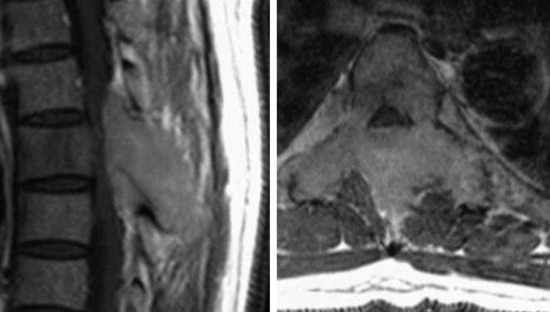

• The low signal intensity on T2WI and the rich enhancement correlate well with the histologic findings of fibroblasts and vascularization, respectively (Fig. 3-33).14

OSTEOLYTIC METASTASIS

EPIDEMIOLOGY

• Vertebral metastases are more common in the adult population, particularly in patients with advanced disease.

HISTOLOGY

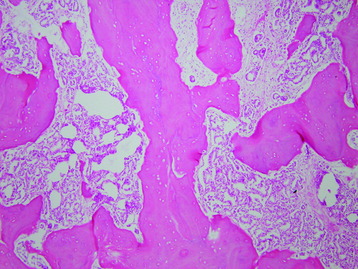

• Metastatic carcinomas are histologically discrete aggregates of neoplastic cells (Figs. 3-34 and 3-35).

• The metastatic tumor may or may not share identical cytoarchitectural features with the primary tumor. However, when presented with a metastatic lesion, efforts should be made to concurrently review a patient’s prior relevant pathology specimens.

• For metastatic lesions of unknown primary tumor, immunohistochemical panels can be diagnostic or help narrow the possible primary sites (Fig. 3-36).

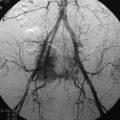

RADIOLOGY

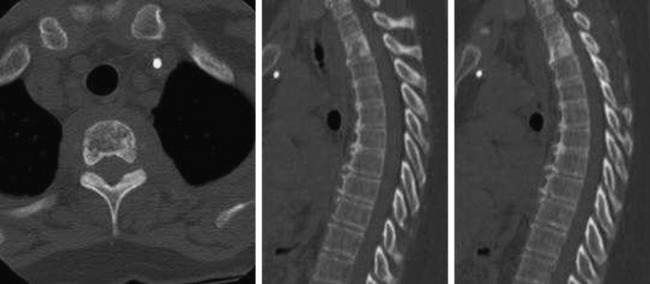

• On radiography, osteolytic metastasis can be detected as absent pedicles, disappearance of cortical line, or compression fractures (Fig. 3-37).

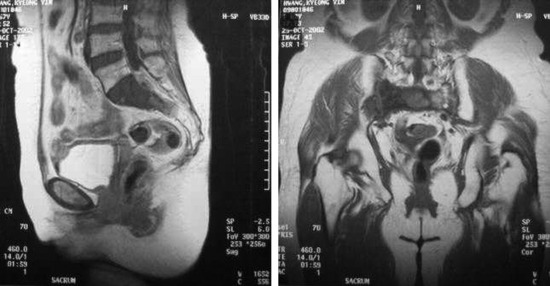

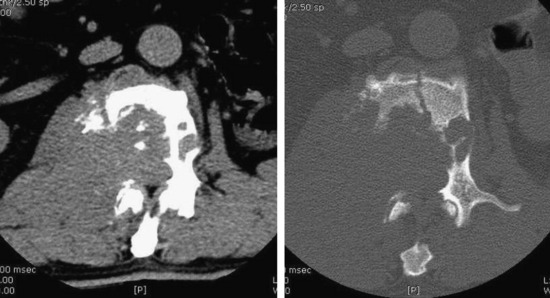

• Bone destruction is best diagnosed with CT scan. Usually posterior cortical destruction is seen, and paraspinal or epidural soft tissue mass formation is observed (Fig. 3-38).

• MRI shows low signal change on T1WI and high signal change on T2WI. In most cases, a diffuse enhancement pattern is shown. The necrotic part of the tumor mass is not enhanced (Fig. 3-39). The extent of soft tissue mass is best diagnosed with MRI.

OSTEOBLASTIC METASTASIS

EPIDEMIOLOGY

DISTRIBUTION

• Backward pathway through veins from the prostate to the spine has been proposed for the metastatic mechanism of prostate cancer.

• There is a reported inverse relationship between spine and lung metastases, suggesting that metastasis to the spine is independent of lung metastasis.17

• The maximum frequency of spine involvement occurred in smaller tumors (4–6 cm) as compared with the maximum spread to lung (6–8 cm) and liver (>8 cm), suggesting that spine metastases precede lung and liver metastases in many prostate cancers. There is a gradual decrease in spine involvement from the lumbar to the cervical level (97% vs. 38%), which is consistent with a subsequent upward metastatic spread along spinal veins after initial lumbar metastasis.

HISTOLOGY

RADIOLOGY

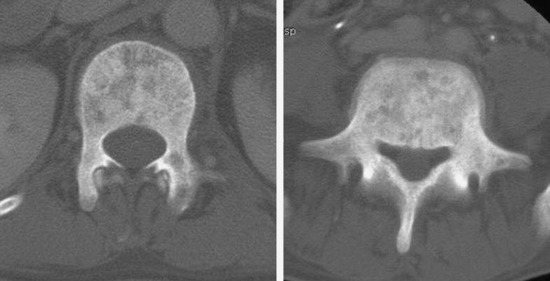

• On radiography, dense sclerotic foci involve the vertebral body, pedicle, and posterior element. Generally, a high density change of the vertebral body is seen (Fig. 3-41). Sometimes compression fracture is detected.

• With CT scan, the bone marrow is replaced with dense foci of sclerosis. When the sclerotic change appears in diffuse pattern, this phenomenon is called an ivory vertebra (Fig. 3-42).

SOLITARY BONE PLASMACYTOMA

EPIDEMIOLOGY

DISTRIBUTION

HISTOLOGY

• Monotonous collection of neoplastic plasma cells; eccentric, round, moderately pleomorphic nuclei with a “clock face” chromatin; and rich basophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 3-44).

• Immunohistochemical staining is necessary to confirm plasma cell lineage and monoclonality (see Fig. 3-44, B, C, and D).

RADIOLOGY

• On radiography, the lesion is usually large, well defined, expanded and cystic-appearing, and may have permeative components.

• The CT appearance of plasmacytoma is that of lytic abnormalities with sclerotic margins without the usual focal punch-out appearance as in multiple myeloma.20

• On MRI studies, the mass lesion is isointense or slightly hyperintense on T1WI and hypointense on T2WI, and shows weak homogeneous enhancement (Figs. 3-45 and 3-46).

FIBROSARCOMA

EPIDEMIOLOGY

HISTOLOGY

• Among malignant mesenchymal tumors, fibrosarcoma is one of the neoplasms with a well known histologic variability.

• Histologically low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant collagen rosettes, and sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma are well established entities.22

• Recently fibrosarcoma of low-grade fibroblastic type, a new entity, is categorized as a diagnosis of exclusion.

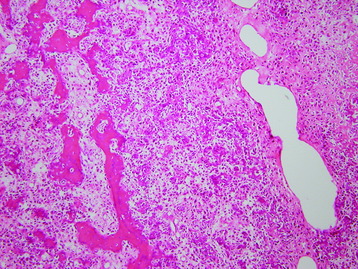

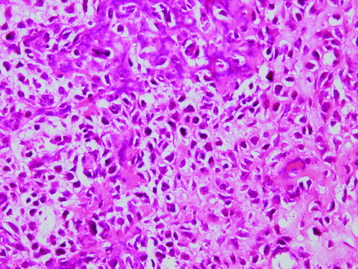

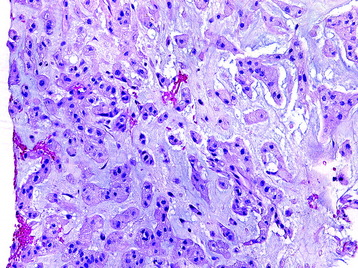

• The individual tumor cell has a monotonous appearance, consisting of polygonal cells arranged in a herringbone pattern surrounded by dense collagenous stroma with areas of hyalinization (Fig. 3-47).

• The tumor infiltrates into the surrounding cortical lamellar bone. When tumor cells are observed under high-power magnification, they are rounded, oval, or polygonal; of small to medium size; and with clear or pale eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 3-48).

• The nuclei of the tumor cells are small, ovoid, or angular and mostly pale or vesicular, with distinct nucleoli and little pleomorphism. Some of the tumor cells show clear or vacuolated cytoplasm, but they constitute less than 20% of the tumor.

• Differential diagnosis includes benign fibrous lesions, low-grade myofibroblastic sarcoma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor.