CHAPTER 323 Epidemiology of Traumatic Brain Injury

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) constitutes a critical public health and socioeconomic problem throughout the world.1–3 It is the leading cause of mortality and disability among young individuals in high-income countries. Worldwide, the incidence of TBI is rising sharply, mainly because of increasing motor vehicle use in low- and middle-income countries.

TBI will surpass many diseases as the major cause of death and disability by the year 2020.4 It is often referred to as a silent epidemic5—silent because patients are not vociferous as a consequence of the nature of the disease and its sequelae, as well as because society in general is largely unaware of the magnitude of the problem.

Definitions

Epidemiology

The prevalence of TBI is the total volume of TBI (existing plus new cases) at a given point (point prevalence) or in a given period (period prevalence). It should encompass all persons living with the sequelae of TBI, such as handicaps, impairments, disabilities, and complaints, together with all new TBIs. Unfortunately, very few longitudinal studies exist, follow-up is often short, and loss to follow-up is frequent in TBI cohorts.6

For these reasons, the use of a standardized mortality rate is generally accepted in many fields of medicine. Standardized mortality rates compare the number of expected deaths with the number of observed deaths. This indirect standardization method adjusts for differences in baseline characteristics to permit comparisons over time or between different settings. Standardized mortality rates are generally adjusted for age and sex. In intensive care medicine, standardized mortality rates are adjusted for baseline characteristics and based on scoring systems such as the Acute Physiology, Age, and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II; the Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS); or the Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) 2/3. These prognostic scores, however, have not been developed specifically for TBI, and their applicability to TBI is doubtful. We see a clear need for developing a system to calculate standardized mortality rates in the field of TBI that adjusts for baseline characteristics, is available on admission, and uses prognostic models.7

Limitations and Gaps in Our Knowledge of the Epidemiology of Traumatic Brain Injury

Ongoing efforts to quantify the magnitude of the problem posed by TBI are limited by many factors.

We recently proposed the following definition for TBI: “brain damage resulting from external forces, as a consequence of direct impact, rapid acceleration or deceleration, a penetrating object (e.g., gunshot) or blast waves from an explosion. The nature, intensity, direction and duration of these forces determine the pattern and extent of damage.”8 Other definitions also include patients with subtle behavioral or neuropsychological changes reported at some time after possibly trivial injury. In addition, it has been suggested that patients who at the time of injury have an alteration in mental state (e.g., confusion, disorientation, slowed thinking) be included in the definition of TBI.

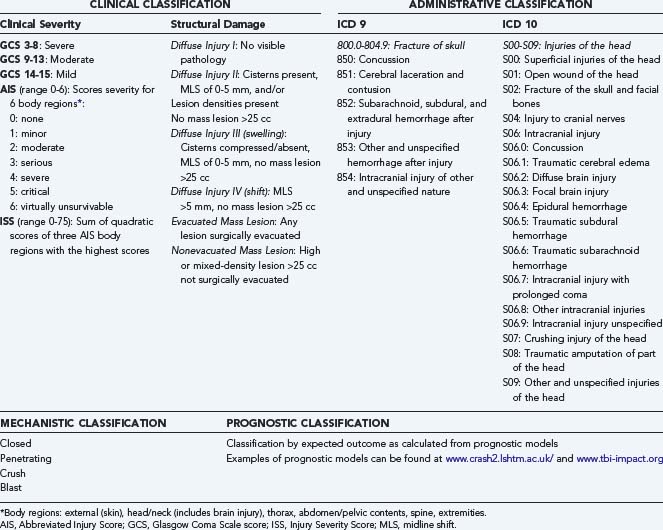

Fourth, when data are collected, they are often identified by codes of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), which were more pathologically based in the ICD 9 classification (Table 323-1), whereas the newest ICD 10 classification is more clinically oriented. Neither of these two classification systems, however, capture reliable information on the severity of injury. Both the ICD 9 and ICD 10 classification systems are primarily intended for administrative use and therefore have substantial limitations.

Classification of Traumatic Brain Injury

Epidemiologic studies on TBI are more or less based exclusively on the administrative classification of the ICD 9 or ICD 10 codes. In ICD 9, different codes are not mutually exclusive, which results in problems and variability in coding, and the coding in no way reflects the actual clinical severity of injury.9 Similar criticism is applicable to the ICD 10 codes. High agreement (96.5%) between the ICD 9 and ICD 10 codes in identifying TBI has been reported.10

In clinical medicine, scoring systems are frequently used to classify the severity of injury (see Table 323-1). The clinical severity of intracranial injuries is commonly assessed according to the degree of depression of the level of consciousness as assessed by the GCS.11 The GCS consists of the sum score (range, 3 to 15) of three components (eye, motor, and verbal scales), each assessing different aspects of reactivity. The motor component provides more discrimination in patients with severe injuries, whereas the eye and verbal scales are more discriminative in patients with moderate and mild injuries. For assessment of severity in individual patients, the three components should be reported separately. For purposes of classification, however, calculation of the sum score is useful. Severe TBI is defined as a GCS score of 3 to 8, moderate TBI as a GCS score of 9 to 13, and mild TBI as a GCS score of 14 to 15. A limitation of classifying clinical severity with the GCS is that accurate assessment may be confounded by the prehospital use of sedation and paralysis.12,13 The severity of extracranial injuries is commonly scored according to the Abbreviated Injury Score (AIS)14 or the Injury Severity Score (ISS).15 TBI is associated with extracranial injuries (limb fractures, thoracic or abdominal injuries) in about 35% of patients.16 Extracranial injuries increase the risk for secondary damage as a result of hypoxia, hypotension, pyrexia, and coagulopathy. In the assessment of overall injury severity, therefore, recording of the severity of extracranial injuries is highly relevant.

Assessment of the extent of structural damage is commonly performed according to the Marshall CT classification. This classification was proposed by Marshall and colleagues in 1991 as a descriptive system that focused on the presence or absence of a mass lesion.17 The scale further differentiates diffuse injuries by signs of increased intracranial pressure (e.g., compression of the basal cisterns, midline shift). This classification has limitations, however, such as broad differentiation between diffuse injuries and mass lesions and lack of specification. For purposes of prognosis, better discrimination can be obtained by combining information available from individual CT characteristics into a prognostic model. A score chart for applying such a score has been proposed by Maas and associates.18 A different approach to classifying patients is by prognostic risk. Recently, well-validated models developed from large patient samples have become available to facilitate this approach.19,20 Prognostic classification can serve various purposes, including comparison of different TBI series, quality assessment for the delivery of health care, and support of the analysis of clinical trials. All these approaches to classification are characterized by some form of scoring of severity.

The Impact of Traumatic Brain Injury from A Global Perspective

TBI is a major health and socioeconomic problem that affects all societies around the world. Globally, in excess of 10 million people suffer TBI serious enough to result in death or hospitalization each year.21 In 2003, in the United States alone there were an estimated 1,565,000 TBIs resulting in 1,224,000 emergency department visits, 290,000 hospital admissions, and 51,000 deaths.22 The prevalence of TBI in the United States has been estimated at approximately 5.3 million. In the European Union with 330 million inhabitants, approximately 7,775,000 new TBI cases occur each year. Worldwide, TBI will surpass many diseases as the major cause of death and disability by the year 2020.4 It has been estimated that TBI accounts for 9% of global mortality and is a threat to health in every country in the world. For every death there are dozens of hospitalizations, hundreds of emergency department visits, and thousands of doctor appointments. A large proportion of people surviving their injuries incur temporary or permanent disability. Brain trauma accounts for approximately a third of all injury-related deaths and the majority of permanent disability. Despite the success of preventive measures, injuries, including unintentional injuries, homicide, and suicide, are the leading cause of death in the United States and Europe in individuals younger than 45 years. In low- and middle-income countries, the incidence of TBI is rising sharply because of increasing motorization. Most patients with TBI have milder injuries, but residual deficits are common.23 TBI occurs more frequently in young adults, particularly males, and has a high cost to society because of life years lost as a result of death and disability. The financial burden of TBI has been estimated to be greater than $60 billion per year in the United States alone.24 The true cost is even higher in that this figure does not address the indirect effects on families or other caregivers. These numbers stand in stark contrast to the amount of funding for TBI research, which has one of the highest unmet needs within the already severely underfunded field of brain research.

Incidence

Given the gaps and limitations in our knowledge of the epidemiology of TBI described previously, the epidemiologic data reported in the literature need to be interpreted with great caution. Table 323-2 presents a summary overview of reported incidence rates across the world.6,10,25–40

TABLE 323-2 Incidence of Traumatic Brain Injury across the World

| REGION | INCIDENCE/100.000 | REFERENCE |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 103 | Kelly and Becker,25 2001; Thurman et al.,26 1999; Langlois et al.,10 2006 |

| European Union | 235 | Tagliaferri et al.,6 2006 |

| Germany | 340 | Firsching and Woischneck,27 2001 |

| Italy | 212-372 | Servadei et al., 1988,28 200229; Baldo, et al.,30 2003 |

| Denmark | 157-265 | Engberg and Teasdale,31 2001 |

| Finland | 101 | Koskinen and Alaranta,32 2008 |

| Norway | 83-229 | Ingebrigtsen et al.,33 1998; Andelic et al.,34 2008 |

| Sweden | 354-546 | Andersson et al.,35 2003; Styrke et al.,36 2007 |

| Brazil | 360 | Maset et al.,37 1993 |

| China | 55-64 | Zhao and Wang,38 2001 |

| Pakistan | 50 | Raja et al.,39 2001 |

| South Africa | 316 | Nell and Brown,40 1991 |

This table illustrates the large variation in reported incidence rates, which is primarily due to varying definitions of injury, different inclusion criteria in addition to actual differences, and sampling errors.41 The approximate incidence of 103 per 100,000 for the United States represents the best estimate from CDC data.10 Kelly and Becker reported a range of 132 to 367 per 100,000 with an estimate of around 100 per 100,000 at the time of the study in 2001.25 Thurman and colleagues reported a decrease in incidence of 234 per 100,000 in 1975 to 90 per 100,000 in 1994.26

The overall incidence of 235 per 100,000 reported by Tagliaferri and colleagues in 2006 is derived from a systematic review of 23 reports on national and regional epidemiologic studies carried out on TBI in Europe.6 Wide variation in reported incidence ranging from 20 (only neurosurgical cases) to 546 (including emergency department visits, hospital discharge, and coroner reports) was noted. This latter figure is very consistent with the 538 per 100,000 reported for the United States in a nationwide survey, including emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths.22 A number of studies from Italy show relatively limited variability, with reported incidence figures of 212 to 372 per 100,000 per year, but in these studies inclusion criteria are also different. Some include tourists in a population-based analysis; others were performed in relatively small regions, which results in a referral bias because of transport of severe cases within the region.28,29,30,42 A number of studies have shown important regional variations. Population-based studies from Norway report an incidence of 229 per 100,000 in more rural areas33 and 83.3 per 100,000 in the Oslo area.34 Styrke and coworkers found an incidence of 354 per 100,000 in northern Sweden in 2007,36 as opposed to 546 per 100,000 in western Sweden.35 In Taiwan, the incidence in Taipei is approximately 218 per 100,000 versus 417 per 100,000 in more rural areas.43,44 Similar differences have also been reported in Australia.45

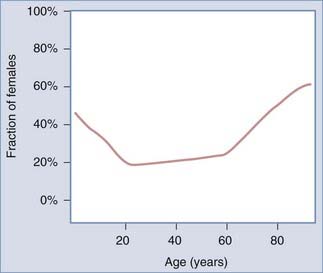

TBI is generally thought to occur predominantly in young adult males with a male-to-female ratio of 3:1.46 Recent studies from the International Mission for Prognosis And Clinical Trial (IMPACT) study group, however, have shown that the male preponderance decreases at lower and higher age groups and that in children, as well as in the elderly older than 65 to 70 years, there is no clear gender difference in the incidence of TBI (Fig. 323-1).

FIGURE 323-1 Male preponderance in traumatic brain injury is limited to those aged 20 to 60 years.

(From Mushkudiani NA, Engel DC, Steyerberg EW, et al. Prognostic value of demographic characteristics in traumatic brain injury: results from the IMPACT study.

Certain groups of the population are at increased risk for sustaining TBI. Slaughter and colleagues47 and Morrell and associates48 have indicated that a large percentage of persons detained in penal institutions report a history of head injury. Military personnel are at particularly high risk for TBI. Ivins and coauthors reported that up to 23% of noncombat active-duty soldiers had sustained some form of TBI during their military service.49 Experience in Iraq and Afghanistan indicates a high risk for concussion and more severe TBI as a result of blast injuries.50,51 A subpopulation particularly vulnerable is young children, in whom inflicted injury has just recently been studied. An incidence of 17 per 100,000 together with a risk profile should lead to more effective preventive interventions.52

Mortality Rates

Given the great variability in data collection and lack of standardization, comparison of mortality rates between different studies is virtually impossible. Data available in the literature indicate variability from 6.3 to 39.3 per 100,000 (Table 323-3).6,22,27,38,53–57

TABLE 323-3 Mortality Rate after Traumatic Brain Injury across the World

| REGION | INCIDENCE/100.000 | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 17.5-24.6 (1979-2003) | Adekoya et al.,53 2002; Rutland-Brown et al.,22 2006 |

| West Virginia | 23.6 (1989-1999) | Adekoya and Majumder,54 2004 |

| European Union | 15* | Tagliaferri et al.,6 2006 |

| Germany | 11.5 | Firsching and Woischneck,27 2001 |

| Austria | 40.8 (SDR) | Rosso et al.,55 2007 |

| Finland | 21.2 | Sundstrom et al.,56 2007 |

| Denmark | 11.5 | Sundstrom et al.,56 2007 |

| Norway | 10.4 | Sundstrom et al.,56 2007 |

| Sweden | 9.5 | Sundstrom et al.,56 2007 |

| Brazil | 26.2-39.3 | Koizumi et al.,57 2000 |

| China | 6.3 (city)-9.7 (rural) | Zhao and Wang,38 2001 |

SDR, standardized death rate.

* Mortality rate in the hospital, 5.2; mortality rate including all in-hospital and prehospital deaths, 24.4.

These data should, however, be interpreted with great caution. The relatively low rates reported in the People’s Republic of China, for instance, are difficult to understand. These data are based on the results of two large-scale epidemiologic investigations by qualified neurologists and neurosurgeons.38 In 1983, a door-to-door survey in six cities evaluated 63,195 people and a rural survey evaluated 246,812; the point lifetime prevalence was 783.3 per 100,000 in the cities and 442 per 100,000 in rural areas. These studies also showed a mortality rate of 6.3 in the cities and 9.7 per 100,000 in the more rural populations. The relatively low mortality in conjunction with the high prevalence and incidence found in these studies would signify a substantial selection bias causing under reporting of mortality. The average mortality rate in Europe is reported to be around 15 per 100,000.6 However, this figure ranges from 5.2 per 100,000 in a population in France in which only in-hospital deaths after severe TBI were counted to 24.4 per 100,000 in a province in Italy in which all in-hospital and prehospital deaths were recorded. Standardized death rates were reported from Austria in one series.55 Various studies have reported a decline in mortality after TBI. In the United States, Adekoya and coworkers53 and Rutland-Brown and associates22 noted a decrease in TBI-related deaths from 24.6 to 17.5 per 100,000 over the years 1997 to 2003. The decrease in death and disability after TBI in western society is thought to be the combined result of the effects of prevention, improvements in emergency medical systems, trauma organizations, and implementation of guidelines. Studies from Scandinavia have likewise shown a significant decrease in mortality from 1987 to 2001, which was more pronounced in younger patients, and the factor contributing to this decrease is thought to be mainly the success of injury prevention efforts. In Australia, despite a 40% increase in population and a 120% increase in the number of registered vehicles, the amount of fatalities from road incidents* decreased by 47% between 1970 and 1995.58 This coincided with recognition of the importance of public education and implementation of a uniform code of road safety backed by legislation and police enforcement. Most important in these preventive measures appear to be strict limits in blood alcohol concentration, the use of seat belts and a separate child restraint law, firmly enforced speed limits, and compulsory helmets for motorcycle riders. In addition to these measures, clinical care improved as a result of faster communication, better trauma systems, increased availability of CT, and improved intensive care unit facilities and management. These data indicate that the effects of prevention in reducing the burden of disease resulting from TBI are probably far greater than any improvement in the results of treatment.

Cause of Injury

The main causes of neurotrauma are transportation incidents, falls, and gunshot wounds. These injuries, caused by misadventure, violence, or carelessness, all reflect societal behavior. Gilbert stated that the motorcar “had emerged as the most persistent killer in the western world.”59 Road traffic injuries place an enormous strain on a country’s health care system and on the national economy in general. A notable difference exists between the mechanism of TBI sustained in road traffic incidents in high-income countries and that in low/middle-income countries. In high-income countries the victims are generally young adult drivers, whereas in low- and middle-income countries, TBI is suffered much more frequently by “vulnerable” road users, such as pedestrians, cyclists, motorcyclists, and users of public transport. Traffic fatality rates have increased by 44% in Malaysia, by up to 243% in China, and even by up to 383% in Botswana. The observation that it is primarily vulnerable road users who are victims of TBI suggests that it is possibly not so much reckless driving as unawareness of traffic risks in the general population. Consequently, perhaps it may be better to target prevention campaigns in these countries not so much toward drivers but more toward the general population. Moreover, in Pakistan the vast majority of TBI victims from road traffic incidents are pedestrians hit by a vehicle or persons falling from a moving vehicle.39

Hyder and coauthors reported that in general, 60% of TBIs are due to road traffic incidents, 20% to 30% are due to falls, approximately 10% are due to violence, and another 10% result from work- and sports-related injuries.3 In a meta-analysis of individual patient data after moderate and severe TBI, the IMPACT study group found a very similar distribution, with the proportion of road traffic incidents varying from 53% to 80% and the proportion of falls from 12% to 30%.60 Falls are increasing as a cause of injury, particularly in northern Europe.

Other causes of trauma also show regional variation and changing trends. In the United States, firearm injuries exceeded road traffic incidents for the first time in 1990, and this trend contrasted with the fall in deaths from road traffic incidents.61 More than half of cranial gunshot injuries represent suicide attempts.62

Interpersonal violence is reported as the cause of closed head injury in approximately 7% to 10% of patients,22,60,63 a substantial increase over earlier studies. A recent Chinese study in which violent head trauma was analyzed in 11 hospitals over a 5-year period reported that 9.5% of all head injuries have a violence-related cause,63 including trauma by blunt objects (56%), sharp objects (12%), gunshots (0.4%), and other means (31.6%). In this study, males and young adults were most likely to sustain violent head trauma. Most of these injuries were relatively mild, with a GCS score of 13 to 15 in 83% despite the frequent occurrence of skull fractures, contusions, and intracranial hemorrhage. Various studies report that victims of TBI caused by interpersonal violence tend to be male, nonwhite (56% African American), unemployed at the time of the injury, and unmarried and to have a history of illegal substance use and law enforcement encounters. In the Transkei region of South Africa, an association has been described between violence-related TBI and unemployment, poverty, and low educational level.64 Violence is by definition an integral part of armed conflicts. Although in previous conflicts shell and shrapnel injuries were the most common mode of injury causing TBI, at present blast injuries are being seen and recognized with greater frequency. Thoracic and abdominal injuries were often lethal in the past, but more effective body armor has improved survival from these injuries significantly and resulted in an increased incidence of injuries in less protected areas, including the head. Blast injuries are now recognized as a separate entity; although the pathophysiology of blast injuries has not yet been well characterized, prominent features of more severe injuries are vasospasm and early brain swelling. The results of aggressive management, including early decompressive craniectomy, are encouraging. The diagnosis of mild TBI after blast injuries is more difficult, however. Frequently, subtle and transient symptoms are reported, and they may overlap with symptoms caused by posttraumatic stress disorders and postconcussion syndromes. For example, some authors classify patients as having mild TBI when “any alteration in mental state at the time of injury (confusion, disorientation, slowed thinking etc.)” is present, even though specific evidence of amnesia is lacking. Likewise, others may include patients reporting some mental complaints after injury as having sustained TBI. Because of these ambiguities, universal screening of military personnel is not performed in the United Kingdom.65 However, in the United States an extensive program for screening and studying military TBI exists and has resulted in a much higher reported prevalence than in the United Kingdom. Whether these differences represent under reporting in the United Kingdom or over-reporting in the United States remains a matter of speculation. Nonetheless, the differences do confirm that retrospective identification of mild TBI in military personnel who have been in high-stress situations is complex and that it is difficult to distinguish mild TBI from, for example, posttraumatic stress syndrome.

Sports- and recreation-related TBI is currently being recognized more frequently. In the United States, the CDC estimates that between 1.6 and 3.8 million sports-related TBIs occur each year, including those for which no medical care is sought.66 Particular attention is focused on secondary prevention because repeated concussions may have cumulative effects as a result of increased vulnerability of the brain after earlier injury.

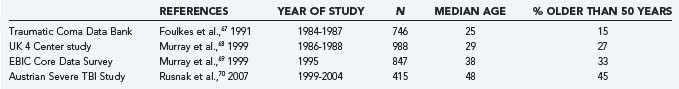

Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury Are Aging

In a comparison of the median age and proportion of TBI patients older than 50 years in observational studies conducted in the 20-year period from 1984 to 2004, a consistent increase is seen (Table 323-4).67–70 This increase in the age profile of TBI patients is probably due to a combination of factors. First, traffic safety laws and preventive measures have reduced the incidence of TBI secondary to traffic incidents, which primarily occur in younger patients. As a consequence, the relative incidence of TBI caused by falls is increasing, and there is also an absolute increase because falls occur more frequently as life expectancy increases and the population ages. This trend has been examined in detail in Finland. Kannus and colleagues showed an increase in fall-induced head injury over time from 1970 to 1995, even after correction for demographic changes. The increase in age-adjusted incidence was 6.1% per year and was present in both females and males.71 Over this period the proportion of falls as the cause of severe head injury in patients older than 60 years increased from 41% to 63%, and the mean age of severely head injured patients increased from 69.6 to 75 years. In a second study, an alarming rise over the period 1970 to 2004 was found in the incidence of fall-induced TBI in patients older than 80 years. Mortality was high and functional outcome poorer in elderly patients.72 A complicating factor in the pathophysiology of TBI in elderly patients is the high prevalence of the use of anticoagulants, which are associated with an increased risk for intracranial hemorrhage. In this regard, it should be remembered that an elderly patient maintained on anticoagulant therapy in whom an acute subdural hematoma develops after an initial lucid interval is similar to a younger patient with an epidural hematoma (and secondary brain compression) from a pathophysiologic perspective. Thus, similar pathophysiologic entities may have a different course and pathophysiology at different age levels. From a prognostic perspective, specific threshold values do not exist.46 The effect of age on epidemiology, pathophysiology, and outcome after TBI is highly relevant but lies on a continuum. Paradigm shifts in our approaches to TBI prevention, management of TBI, and post-TBI care for the elderly population will need to be made as the population ages and our insight into the entity of TBI increases. More importantly, an increase in facilities for long-term treatment and care will be needed.

The Long and Winding Road of the Epidemiology of Traumatic Brain Injury

TBI affects all communities, all age groups, and all societies across the world. Globally, the burden caused by TBI to patients, relatives, caretakers, and society is increasing. TBI is by definition a heterogeneous disease, and there are also important regional variations in epidemiology and outcome. There is a great lack of adequate, comprehensive data on the incidence of TBI in any community, most of all in communities that have the major burden of neurotrauma. Neurotrauma is a particular burden in developing countries, which have the least capacity to manage it. Successful prevention and reduction of the incidence of neurotrauma can occur only with greater political action, public awareness, and the participation of societies.73

Bruns JJr, Hauser WA. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: a review. Epilepsia. 2003;44(suppl 10):2-10.

Cole TB. Global road safety crisis remedy sought: 1.2 million killed, 50 million injured annually. JAMA. 2004;291:2531-2532.

Hillier SL, Hiller JE, Metzer J. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury in South Australia. Brain Inj. 1997;11:649-659.

Ivins BJ, Schwab KA, Warden D, et al. Traumatic brain injury in the US army paratroopers: prevalence and character. J Trauma. 2006;55:617-621.

Jiang J, Feng H, Fu Z. Violent trauma in China: report of 2254 cases. Surg Neurol. 2007;68:2-5.

Koskinen S, Alaranta H. Traumatic brain injury in Finland 1991-2005: a nationwide register study of hospitalized and fatal TBI. Brain Inj. 2008;22:205-214.

Langlois JA, Sattin RW. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: research and programs of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2005;20:187-188.

Maas AI, Hukkelhoven CW, Marshall LF, et al. Prediction of outcome in traumatic brain injury with computed tomographic characteristics: a comparison between the computed tomographic classification and combinations of computed tomographic predictors. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:1173-1182.

Maas AI, Stocchetti N, Bullock R. Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:728-741.

Marshall LF, Marshall SB, Klauber MR. A new classification of head injury based on computerized tomography. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:S14-S20.

MRC CRASH Trial CollaboratorsPerel P, Arango M, Clayton T, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: practical prognostic models based on large cohort of international patients. BMJ. 2008;336:425-429.

Rutland-Brown W, Langlois JA, Thomas KE, et al. Incidence of traumatic brain injury in the United States, 2003. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:544-548.

Saatman KE, Duhaime AC, Bullock R, et al. for the Workshop Scientific Team and Advisory Panel Members. Classification of traumatic brain injury for targeted therapies. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25:719-738.

Steyerberg EW, Mushkudiani N, Perel P, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: development and international validation of prognostic scores based on admission characteristics. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e165.

Stocchetti N, Pagan F, Calappi E, et al. Inaccurate early assessment of neurological severity in head injury. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:1131-1140.

Tagliaferri F, Compagnone C, Korsic M, et al. A systematic review of brain injury epidemiology in Europe. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2006;148:255-268.

Thurman DJ. Epidemiology and economics of head trauma. In: Miler L, Hayes R, editors. Head Trauma: Basic, Preclinical, and Clinical Directions. New York: Wiley & Sons; 2001:1193-1202.

Warden D. Military TBI during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:398-402.

1 Ghajar J. Traumatic brain injury. Lancet. 2000;356:923-929.

2 Cole TB. Global road safety crisis remedy sought: 1.2 million killed, 50 million injured annually. JAMA. 2004;291:2531-2532.

3 Hyder AA, Wunderlich CA, Puvanachandra P, et al. The impact of traumatic brain injuries: a global perspective. NeuroRehabilitation. 2007;22:341-353.

4 Lopez AD, Murray CC. The global burden of disease, 1990-2020. Nat Med. 1998;4:1241-1243.

5 Langlois JA, Sattin RW. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: research and programs of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2005;20:187-188.

6 Tagliaferri F, Compagnone C, Korsic M, et al. A systematic review of brain injury epidemiology in Europe. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2006;148:255-268.

7 Saatman KE, Duhaime AC, Bullock R, et al. for the Workshop Scientific Team and Advisory Panel Members. Classification of traumatic brain injury for targeted therapies. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25:719-738.

8 Maas AI, Stocchetti N, Bullock R. Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:728-741.

9 Jennett B. Epidemiology of head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;60:362-369.

10 Langlois J, Rutland-Brown W, Thomas K. Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths. Atlanta, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2006.

11 Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81-84.

12 Balestreri M, Czosnyka M, Chatfield DA, et al. Predictive value of Glasgow Coma Scale after brain trauma: change in trend over the past ten years. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:161-162.

13 Stocchetti N, Pagan F, Calappi E, et al. Inaccurate early assessment of neurological severity in head injury. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:1131-1140.

14 Copes WS, Sacco WJ, Champion HR, et al. Progress in characterising anatomic injury. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine, Baltimore, 1990:205-218.

15 Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon WJr, et al. The Injury Severity Score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974;14:187-196.

16 Gennarelli TA, Champion HR, Sacco WJ, et al. Mortality in patients with head injury and extracranial injury treated in trauma centers. J Trauma. 1990;29:1193-1202.

17 Marshall LF, Marshall SB, Klauber MR. A new classification of head injury based on computerized tomography. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:S14-S20.

18 Maas AI, Hukkelhoven CW, Marshall LF, et al. Prediction of outcome in traumatic brain injury with computed tomographic characteristics: a comparison between the computed tomographic classification and combinations of computed tomographic predictors. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:1173-1182.

19 MRC CRASH Trial CollaboratorsPerel P, Arango M, Clayton T, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: practical prognostic models based on large cohort of international patients. BMJ. 2008;336:425-429.

20 Steyerberg EW, Mushkudiani N, Perel P, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: development and international validation of prognostic scores based on admission characteristics. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e165.

21 World Health Statistics. Global Health Statistics, 2007, 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Available at http://www.who.int/whosis/en/

22 Rutland-Brown W, Langlois JA, Thomas KE, et al. Incidence of traumatic brain injury in the United States, 2003. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:544-548.

23 Thornhill S, Teasdale GM, Murray GD, et al. Disability in young people and adults one year after head injury: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000;320:1631-1635.

24 Thurman DJ. Epidemiology and economics of head trauma. In: Miler L, Hayes R, editors. Head Trauma: Basic, Preclinical, and Clinical Directions. New York: Wiley & Sons; 2001:1193-1202.

25 Kelly DF, DP Becker. Advances in management of neurosurgical trauma: USA and Canada. World J Surg. 2001;25:1179-1185.

26 Thurman DJ, Alverson C, Dunn KA, et al. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: a public health perspective. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1999;14:602-615.

27 Firsching R, Woischneck D. Present status of neurosurgical trauma in Germany. World J Surg. 2001;25:1221-1223.

28 Servadei F, Ciucci G, Piazza G, et al. A prospective clinical and epidemiological study of head injuries in northern Italy: the Comune of Ravenna. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1988;9:449-457.

29 Servadei F, Antonelli V, Betti L, et al. Regional brain injury epidemiology as the basis for planning brain injury treatment. The Romagna (Italy) experience. J Neurosurg Sci. 2002;46(3-4):111-119.

30 Baldo V, Marcolongo A, Floreani A, et al. Epidemiological aspect of traumatic brain injury in Northeast Italy. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18:1059-1063.

31 Engberg AW, Teasdale TW. Traumatic brain injury in Denmark 1979-1996. A national study of incidence and mortality. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17:437-442.

32 Koskinen S, Alaranta H. Traumatic brain injury in Finland 1991-2005: a nationwide register study of hospitalized and fatal TBI. Brain Inj. 2008;22:205-214.

33 Ingebrigtsen T, Mortensen K, Romner B. The epidemiology of hospital-referred head injury in northern Norway. Neuroepidemiology. 1998;17:139-146.

34 Andelic N, Sigurdardottir S, Brunborg C, et al. Incidence of hospital-treated traumatic brain injury in the Oslo population. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;30:120-128.

35 Andersson EH, Bjorklund R, Emanuelson I, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: a population based study in western Sweden. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;107:256-259.

36 Styrke J, Stalnacke BM, Sojka P, et al. Traumatic brain injuries in a well-defined population: epidemiological aspects and severity. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1425-1436.

37 Maset A, Andrade AF, Martucci SC, et al. Epidemiologic features of head injury in Brazil. Arq Bras Neurocirurg. 1993;12:293-302.

38 Zhao YD, Wang W. Neurosurgical trauma in People’s Republic of China. World J Surg. 2001;25:1202-1204.

39 Raja IA, Vohra AH, Ahmed M. Neurotrauma in Pakistan. World J Surg. 2001;25:1230-1237.

40 Nell V, Brown DS. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury in Johannesburg—II. Morbidity, mortality and etiology. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33:289-296.

41 Bruns JJr, Hauser WA. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: a review. Epilepsia. 2003;44(suppl 10):2-10.

42 Servadei F, Verlicchi A, Soldano F, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of head injury in Romagna and Trentino. Neuroepidemiology. 2002;21:297-304.

43 Chiu WT, Hung CC, Shih CJ. Epidemiology of head injury in rural Taiwan: a four year survey. J Clin Neurosci. 1995;2:210-215.

44 Chiu WT, Hung CC, Le LS, et al. Head injury in urban and rural populations in a developing country. J Clin Neurosci. 1997;4:469-472.

45 Hillier SL, Hiller JE, Metzer J. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury in South Australia. Brain Inj. 1997;11:649-659.

46 Mushkudiani NA, Engel DC, Steyerberg EW, et al. Prognostic value of demographic characteristics in traumatic brain injury: results from the IMPACT study. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:259-269.

47 Slaughter B, Fann JR, Ehde D. Traumatic brain injury in a county jail population: prevalence, neuropsychological functioning and psychiatric disorders. Brain Inj. 2003;17:731-741.

48 Morrell RF, Merbitz C, Jain S. Traumatic brain injury in prisoners. J Offender Rehabil. 1998;27:1-8.

49 Ivins BJ, Schwab KA, Warden D, et al. Traumatic brain injury in the US army paratroopers: prevalence and character. J Trauma. 2006;55:617-621.

50 Cavallaro G. A sort of homecoming. War and PCS orders: Carson helps brigade cope. Army Times [serial online] http://www.armytimes.com, September 2005. Available at

51 Warden D. Military TBI during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:398-402.

52 Keenan HT, Runyan DK, Marshall SW, et al. A population-based study of inflicted traumatic brain injury in young children. JAMA. 2003;290:621-626.

53 Adekoya N, Thurman DJ, White DD, et al. Surveillance for traumatic brain injury deaths—United States 1989-1998. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2002;51(10):1-14.

54 Adekoya N, Majumder R. Fatal traumatic brain injury, West Virginia, 1989-1998. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:486-492.

55 Rosso A, Brazinova A, Janciak I, et al. for the Austrian Severe TBI Study Investigators. Severe traumatic brain injury in Austria II: epidemiology of hospital admissions. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2007;110:29-34.

56 Sundstrom T, Sollid S, Wentzel-Larsen T, et al. Head injury mortality in the Nordic countries. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:147-153.

57 Koizumi MS, Lebrao ML, Mello-Jorge MH, et al. Morbidity and mortality due to traumatic brain injury in Sao Paulo City, Brazil 1997. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2000;58:81-89.

58 Atkinson L, Merry G. Advances in neurotrauma in Australia 1970-2000. World J Surg. 2001;25:1224-1229.

59 Gilbert M. A History of the Twentieth Century, Vol 1. London: Harper Collins. 1997.

60 Butcher I, McHugh GS, Lu J, et al. Prognostic value of cause of injury in traumatic brain injury: results form the IMPACT study. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:281-286.

61 Sosin DM, Sniezek JE, Waxweiler RJ. Trends in death associated with traumatic brain injury, 1979 through 1992. JAMA. 1995;273:1778-1780.

62 Aarabi B, Alden TD, Chestnut RM, et al. Management and prognosis of penetrating brain injury—guidelines. J Trauma. 2001;51(suppl):S1-86.

63 Jiang J, Feng H, Fu Z. Violent trauma in China: report of 2254 cases. Surg Neurol. 2007;68:2-5.

64 Meel BL. Incidence and patterns of violent and/or traumatic deaths between 1993 and 1999 in the Transkei region of South Africa. J Trauma. 2004;57:125-129.

65 Hayward P. Traumatic brain injury: the signature of modern conflicts. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:200-201.

66 Langlois JA, Rutland-Brown W, Wald MM. The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:375-378.

67 Foulkes AM, Eisenberg MH, Jane AJ. The Traumatic Coma Data Bank; design, methods and baseline characteristics. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:S1-S15.

68 Murray LS, Teasdale GM, Murray GD, et al. Head injuries in four British neurosurgical centers. Br J Neurosurg. 1999;13:564-569.

69 Murray GD, Teasdale GM, Braakman R. The European Brain Injury Consortium survey of head injuries. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1999;141:223-236.

70 Rusnak M, Janciak I, Majdan M, et al. Austrian Severe TBI Study Investigators. Severe traumatic brain injury in Austria. I: Introduction to the study. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2007;119:23-28.

71 Kannus P, Palvanen M, Niemi S, et al. Increasing number and incidence of fall-induced severe head injuries in older adults: nationwide statistics in Finland in 1970-1995 and prediction for the future. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:143-150.

72 Susman M, DiRusso SM, Sullivan T, et al. Traumatic brain injury in the elderly: increased mortality and worse functional outcome at discharge despite lower injury severity. J Trauma. 2002;53:219-223.

73 Reilly P. The impact of neurotrauma on society: an international perspective. Prog Brain Res. 2007;161:3-9.

* In keeping with current epidemiologic terminology, “road traffic incident” is used through this chapter rather than “road traffic accident.” An accident is considered an event that happens by chance and is therefore not preventable. In contrast, many road traffic injuries are preventable and should therefore not be classified as accidents.