CHAPTER 110 Endovascular Techniques for Tumor Embolization

Endovascular embolization for tumors has been around for more than 30 years and is considered an important adjunct to surgical treatment.1,2 The purpose of embolization is to occlude the vascular supply to the tumor to achieve tumor necrosis and decrease intraoperative blood loss.3 Typically, this procedure is performed on vascular tumors such as hemangioblastomas, paragangliomas, juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas, metastases, hemangiopericytomas, schwannomas, and meningiomas.

Embolization Technique

Diagnostic angiography and tumor embolization are performed 1 to 2 days before the scheduled surgical resection to allow time for tumor necrosis while avoiding neovascularization. However, some report waiting as long as 7 days between embolization and surgery.2 The patient should be well hydrated before the commencement of angiography to protect renal function from the contrast material.

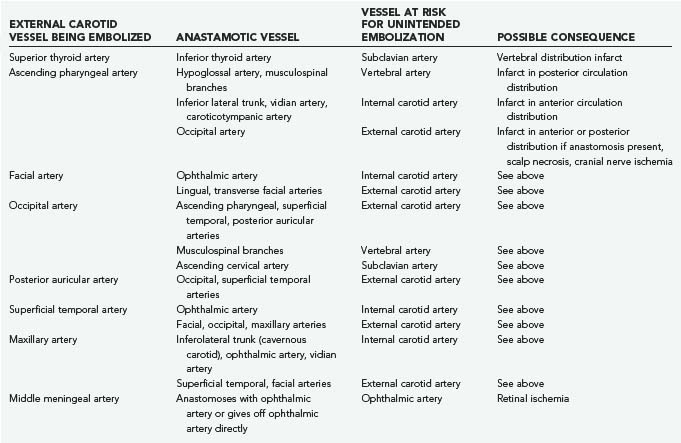

The diagnostic angiogram is extremely important to identify not only the vascular supply to the tumor but also dangerous anastomoses. In-depth knowledge of anatomy and potential external carotid–to–internal carotid anastomoses is essential for performing tumor embolization safely and effectively.4 The most common anastomoses that one must evaluate are listed in Table 110-1. The other pitfall that must be avoided is embolizing the vascular supply to the cranial nerves and roots. Knowledge of the anatomy is essential; however, one should exercise caution and know that vascular distributions are highly variable. If any doubts remain, administering 3 mL of lidocaine and testing for cranial nerve deficits can be performed before embolization.2 Table 110-2 lists the common vascular supply to the cranial nerves and roots. In addition, amobarbital may be used to assess the arterial blood supply to the brain parenchyma.5,6 Monitored anesthesia care is necessary to perform provocative testing. However, some patients cannot tolerate monitored anesthesia care and therefore require general anesthesia. Although general anesthesia negates the use of provocative testing, it does provide some benefits, such as increasing the accuracy of angiography (less motion artifact) and patient comfort (manipulation inside the middle meningeal artery can produce extreme discomfort). Continuous electroencephalographic monitoring along with somatosensory evoked potentials can provide insight that a complication has occurred when general anesthesia is used.

TABLE 110-2 Cranial Nerve Blood Supply from Potentially Embolized Vessels

| CRANIAL NERVE | COMMON ARTERIAL SUPPLY |

|---|---|

| I | Anterior cerebral artery (A2 division) |

| II | Ophthalmic, central retinal, posterior ciliary |

| III | Inferior lateral trunk, meningohypophyseal, marginal tentorial, cavernous branches of ICA |

| IV | Inferior lateral trunk, marginal tentorial |

| V1 | Inferior lateral trunk, middle meningeal, cavernous branches of ICA |

| V2 | Inferior lateral trunk, internal maxillary, cavernous branches of ICA |

| V3 | Middle meningeal, inferior lateral trunk, accessory meningeal |

| VI | Inferolateral trunk, ascending pharyngeal, meningohypophyseal, marginal tentorial, cavernous branches of ICA |

| VII | Middle meningeal, accessory meningeal, occipital |

| IX | Ascending pharyngeal |

| X | Ascending pharyngeal |

| XI | Ascending pharyngeal |

| XII | Ascending pharyngeal |

| C1 + C2 roots | Occipital artery |

ICA, internal carotid artery.

Embolic Agents

Several different agents can be used for tumor embolization (Table 110-3). The agents fall into one of three main categories: liquids, particulates, or coils. The agent selected depends on the presence or possibility of a dangerous anastomosis, the ability to navigate the microcatheter to the ideal location, vascular supply to the cranial nerves, and operator preference. The vasa nervorum are usually less than 150 to 200 µm; therefore, if cranial nerves are at risk, it is recommended that embolic agents larger than 200 µm in size be used.4 The best embolization results are achieved with small or liquid agents that can penetrate the tumor bed and embolize at the capillary level. These agents are also the most dangerous to use because they can damage normal structures as well. Large embolic agents, such as coils or particles larger than 500 µm, are relatively safe but are ineffective if used alone. A good mixture of safety and efficacy is achieved when embolic agents ranging in size from 300 to 500 µm are used.4

| CLASSIFICATION | AGENTS | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|

| Coils | Detachable coils (i.e., GDC, Matrix) | Proximal occlusion only, no effect at the tumor bed. Ineffective when used alone |

| Liquids | ETOH |

ETOH, ethyl alcohol; NBCA, N-butylcyanoacrylate; PVA, polyvinyl alcohol.

Efficacy

The efficacy of tumor embolization is debatable. Several small series published in the literature support the use of tumor embolization and its benefits,7–11 but there are also reports that question the efficacy and utility of preoperative tumor embolization, most notably for meningiomas.12 Currently, the overall consensus within the field of neurosurgery is that preoperative tumor embolization is beneficial in reducing intraoperative blood loss in patients with vascular tumors. However, no large randomized study has demonstrated that preoperative embolization improves outcome or increases surgical success rates.

Meningiomas

Meningiomas are extra-axial tumors that arise from arachnoid cells in the leptomeninges and account for approximately 15% of all intracranial neoplasms.13 These tumors are usually quite vascular because they arise from the dura, which is a heavily vascularized structure.14 Convexity meningiomas seem to have a greater vascular supply than do skull base meningiomas, and the closer the convexity meningioma to the midline, the greater the chance of bilateral supply.4

The complication rate for embolization of meningiomas is low. Lasjaunias and Bernstein reported that 3 of 185 (1.6%) patients had a permanent neurological deficit after embolization,15 and Halbach and colleagues reported a morbidity rate of less than 0.5% after embolization of several hundred meningiomas.4

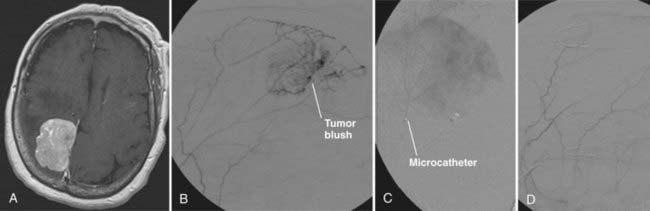

A convexity meningioma is seen in Figure 110-1A. Diagnostic angiography revealed the vascular supply to this tumor to be from branches of the middle meningeal artery (see Fig. 110-1B). Under digital subtraction angiography and road map guidance, a microcatheter was navigated into one of the feeding vessels (see Fig. 110-1C). Embospheres (300 to 500 µm) were then injected into the tumor bed until the tumor blush dissipated (see Fig. 110-1D). This was repeated in all the feeding vessels until tumor blush was no longer visualized.

Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas are rare, highly vascular, benign tumors that occur most commonly in young males.4,16,17 Patients usually complain of epistaxis and nasal obstruction. These tumors originate in the nasopharynx but may extend into the nose or orbit and intracranially.18

Treatment options for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma are surgical resection, radiation therapy, or a combination of the two. However, most agree that surgery is the treatment of choice.19,20 The role of embolization is debated, but because of the extreme vascular nature of these tumors, most recommend preoperative embolization before surgical resection. However, some argue against preoperative embolization because they believe that it contributes to increased recurrence rates and leads to poor surgical resection.21,22

The vascular supply to these tumors primarily arises from branches of the internal maxillary artery, facial artery, ascending pharyngeal artery, and internal carotid artery. These tumors frequently have a bilateral vascular supply, and therefore both carotids should be evaluated.2

Paragangliomas

Paragangliomas are highly vascular tumors that arise from paraganglion cells of the parasympathetic nervous system.23 In the head and neck, these tumors are most commonly located at the jugular fossa, carotid bifurcation, and vagus nerve.2,4

The blood supply to these tumors most commonly arises from the ascending pharyngeal artery, as well as other branches from the external and internal carotid arteries. The structures at risk from embolization of these vessels are listed in Tables 110-1 and 110-2. Occasionally, a large number of branches from the internal carotid artery will supply the tumor, and in patients able to tolerate it, consideration of carotid sacrifice is entertained.

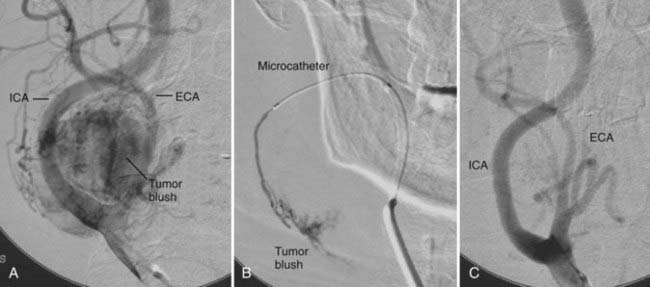

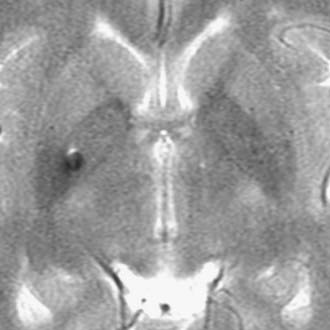

A paraganglioma located at the carotid bifurcation in seen in Figure 110-2A. The diagnostic angiogram revealed that the vascular supply was from both the external and internal carotid arteries. A microcatheter was selectively placed into multiple feeding vessels (see Fig. 110-2B). Polyvinyl alcohol particles were injected into multiple feeding arteries until the tumor blush dissipated (see Fig. 110-2C).

Schwannomas

Schwannomas are slowly growing neoplasms that arise from Schwann cells. They occur on cranial and spinal/peripheral nerves and are the most common tumor found at the cerebellopontine angle. The majority of these tumors are hypervascular, but with an inhomogeneous blush seen on angiography because of areas of avascularity mixed within areas of hypervascularity.4 The ascending pharyngeal artery is the most common arterial blood supply for intracranial schwannomas. These tumors are treated similar to meningiomas, as described earlier.

Hemangiopericytoma

Central nervous system hemangiopericytomas are a rare occurrence and represent less than 1% of all intracranial tumors.24 These tumors were once thought to be a malignant version of meningiomas; however, they do not have the same genetic characteristics as meningiomas, and the World Health Organization has classified them as a separate entity.13,24 These tumors behave much more aggressively than typical meningiomas. They have no gender predilection, occur in a younger age group, and have a tendency to recur with the development of late metastasis when compared with meningiomas.13

In a study evaluating seven patients with hemangiopericytoma, Akiyama and associates reviewed the radiographic images of these tumors. They reported that computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in all seven patients revealed contrast enhancement (four homogeneous on CT and five homogeneous on MRI). Via angiography they found that the feeding vessels to the tumors arose from the pial-cortical vessels in all seven patients, as well as the meningeal-dural vessels in six of the seven patients.24 Only one of the seven patients had a corkscrew vessel within the tumor. All seven tumors were surgically resected, with five of the seven patients sustaining more than 1 L of blood loss, thus revealing how vascular these tumors are.

In other literature, these tumors have been reported to have an arterial supply from branches of the internal carotid artery and vertebrobasilar circulation, as well as from branches of the external carotid artery. The classic angiographic features of these tumors are described as an intense tumor blush with a long-lasting venous phase and corkscrew vessels seen in the tumor itself.2

Akiyama M, Sakai H, Onoue H, et al. Imaging intracranial haemangiopericytomas: study of seven cases. Neuroradiology. 2004;46:194-197.

Barr JD, Mathis JM, Horton JA. Provocative pharmacologic testing during arterial embolization. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1994;5:403-411.

Bendszus M, Rao G, Burger R, et al. Is there a benefit of preoperative meningioma embolization? Neurosurgery. 2000;47:1306-1312.

Chun JY, McDermott MW, Lamborn KR, et al. Delayed surgical resection reduces intraoperative blood loss for embolized meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:1231-1235.

Cummings BJ, Blend R, Keane T, et al. Primary radiation therapy for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:1599-1605.

Deveikis JP. Sequential injections of amobarbital sodium and lidocaine for provocative neurologic testing in external carotid circulation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:1143-1147.

Dowd CF, Halbach V, Higashida R. Meningiomas: the role of preoperative angiography and embolization. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:1-4.

Ellison D, Love S, Chimelli L., et al. Neuropathology. 2004;43:703-716. A reference text of CNS pathology 2nd ed. Mosby

Eskridge J, McAuliffe W, Harris B, et al. Preoperative endovascular embolization of craniospinal hemangioblastomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:525-531.

Gullane PJ, Davidson J, O’Dwyer T, et al. Juvenile angiofibroma: a review of the literature and a case series report. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:928-933.

Gupta R, Thomas AJ, Horowitz M. Intracranial head and neck tumors: endovascular considerations, present and future. Neurosurgery. 2006;59 (suppl 3):S251-S260.

Halbach VV, Hieshima GB, Higashida RT, et al. Interventional Neuroradiology: Endovascular Therapy of the Central Nervous System. 1992.

Hekster RE, Matricali B, Luyendijk W. Presurgical transfemoral catheter embolization to reduce operative blood loss. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1974;41:396-398.

Jafek BW, Nahum AN, Butler RM. Surgical treatment of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Laryngoscope. 1973;83:707-720.

Kerber CN, Newton TN. The macro- and microvasculature of the dura matter. Neuroradiology. 1973;6:175-179.

Lasjaunias P, Bernstein A. Surgical Neuroangiography, Vol 1, Functional Anatomy of Craniofacial Arteries. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1987.

Li JR, Qian J, Shan XZ, Wang L. Evaluation of the effectiveness of preoperative embolization in surgery for nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;225:430-432.

Lloyd G, Howard D, Phelps P, et al. Juvenile angiofibroma: the lessons of 20 years of modern imaging. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:127-134.

Macpherson P. The value of preoperative embolization of meningiomas estimated subjectively and objectively. Neuroradiology. 1991;33:334-337.

Mann WJ, Jecker P, Amedee RG. Juvenile angiofibromas: changing surgical concept over the last 20 years. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:291-293.

Marshall A, Bradley P. management dilemmas in the treatment and follow-up of advanced juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. ORL. 2006;68:273-278.

Noble ER, Smoker WRK, Ghatak NR. Atypical skull base paragangliomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:986-990.

Roberson G, Price A, Davis J, et al. Therapeutic embolization of juvenile angiofibroma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;133:657-663.

Standard SC, Ahuja A, Livingston K, et al. Endovascular embolization and surgical excision for the treatment of cerebellar and brain stem hemangioblastomas. Surg Neurol. 1994;41:405-410.

1 Hekster RE, Matricali B, Luyendijk W. Presurgical transfemoral catheter embolization to reduce operative blood loss. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1974;41:396-398.

2 Gupta R, Thomas AJ, Horowitz M. Intracranial head and neck tumors: endovascular considerations, present and future. Neurosurgery. 2006;59 (suppl 3):S251-S260.

3 Chun JY, McDermott MW, Lamborn KR, et al. Delayed surgical resection reduces intraoperative blood loss for embolized meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:1231-1235.

4 Halbach VV, Hieshima GB, Higashida RT, et al. Interventional Neuroradiology: Endovascular Therapy of the Central Nervous System. 1992.

5 Deveikis JP. Sequential Injections of amobarbital sodium and Lidocaine for provocative neurologic testing in external carotid circulation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:1143-1147.

6 Barr JD, Mathis JM, Horton JA. Provocative pharmacologic testing during arterial embolization. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1994;5:403-411.

7 Macpherson P. The value of pre-operative embolization of meningiomas estimated subjectively and objectively. Neuroradiology. 1991;33:334-337.

8 Standard SC, Ahuja A, Livingston K, et al. Endovascular embolization and surgical excision for the treatment of cerebellar and brain stem hemangioblastomas. Surg Neurol. 1994;41:405-410.

9 Eskridge J, McAuliffe W, Harris B, et al. Preoperative endovascular embolization of craniospinal hemangioblastomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:525-531.

10 Dowd CF, Halbach V, Higashida R. Meningiomas: the role of preoperative angiography and embolization. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15(1):E10.

11 Li JR, Qian J, Shan XZ, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of preoperative embolization in surgery for nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;225:430-432.

12 Bendszus M, Rao G, Burger R, et al. Is there a benefit of preoperative meningioma embolization? Neurosurgery. 2000;47:1306-1312.

13 Ellison D, Love S, Chimelli L, et al, editors. Neuropathology: A Reference Text of CNS Pathology. 2nd ed. Mosby. 2004:703-716.

14 Kerber CN, Newton TN. The macro- and microvasculature of the dura matter. Neuroradiology. 1973;6:175-179.

15 Lasjaunias P, Bernstein A. Surgical Neuroangiography, Vol 1, Functional Anatomy of Craniofacial Arteries. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1987.

16 Roberson G, Price A, Davis J, et al. Therapeutic embolization of juvenile angiofibroma. AJR Am J Neuroradiol. 1979;133:657-663.

17 Gullane PJ, Davidson J, O’Dwyer T, et al. Juvenile angiofibroma: a review of the literature and a case series report. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:928-933.

18 Jafek BW, Nahum AN, Butler RM. Surgical treatment of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Laryngoscope. 1973;83:707-720.

19 Marshall A, Bradley P. Management dilemmas in the treatment and follow-up of advanced juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2006;68:273-278.

20 Cummings BJ, Blend R, Keane T, et al. Primary radiation therapy for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:1599-1605.

21 Lloyd G, Howard D, Phelps P, et al. Juvenile angiofibroma: the lessons of 20 years of modern imaging. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113:127-134.

22 Mann WJ, Jecker P, Amedee RG. Juvenile angiofibromas: changing surgical concept over the last 20 years. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:291-293.

23 Noble ER, Smoker WRK, Ghatak NR. Atypical skull base paragangliomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:986-990.

24 Akiyama M, Sakai H, Onoue H, et al. Imaging intracranial haemangiopericytomas: study of seven cases. Neuroradiology. 2004;46:194-197.