Endocrine and metabolic disorders

Points of note concerning endocrine and metabolic disorders in children are:

Diabetes mellitus

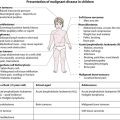

The incidence of diabetes in children has increased steadily over the last 20 years and now affects around 2 per 1000 children by 16 years of age. It has been estimated that the incidence of childhood diabetes will double by 2020 in developed countries. This is most likely to be a result of changes in environmental risk factors, although the exact causes remain obscure. There is considerable racial and geographical variation – the condition is more common in northern countries, with high incidences in Scotland and Finland. Almost all children have type 1 diabetes requiring insulin from the outset. Type 2 diabetes due to insulin resistance is starting to occur in childhood, as severe obesity becomes more common and in some ethnic groups. The other causes of diabetes are listed in Box 25.1.

Aetiology of type 1 diabetes

• An identical twin of a diabetic has a 30–40% chance of developing the disease

• The increased risk of a child developing diabetes if a parent has insulin-dependent diabetes (1 in 20–40 if the father is affected, 1 in 40–80 if it is the mother – compared to about 1/400 in the population <16 years)

• The increased risk of diabetes among those who are HLA-DR3 or HLA-DR4 and a reduced risk with DR2 and DR5.

Molecular mimicry probably occurs between an environmental trigger and an antigen on the surface of β-cells of the pancreas. Triggers which may contribute are enteroviral infections, accounting for the more frequent presentation in spring and autumn, and diet, possibly cow’s milk proteins (Fig. 25.1) and overnutrition. In genetically predisposed individuals, this results in an autoimmune process which damages the pancreatic β-cells and leads to increasing insulin deficiency. Markers of β-cell destruction include islet cell antibodies and antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), the islet cells and insulin. There is an association with other autoimmune disorders such as hypothyroidism, Addison disease, coeliac disease and rheumatoid arthritis in the patient or family history.

Clinical features

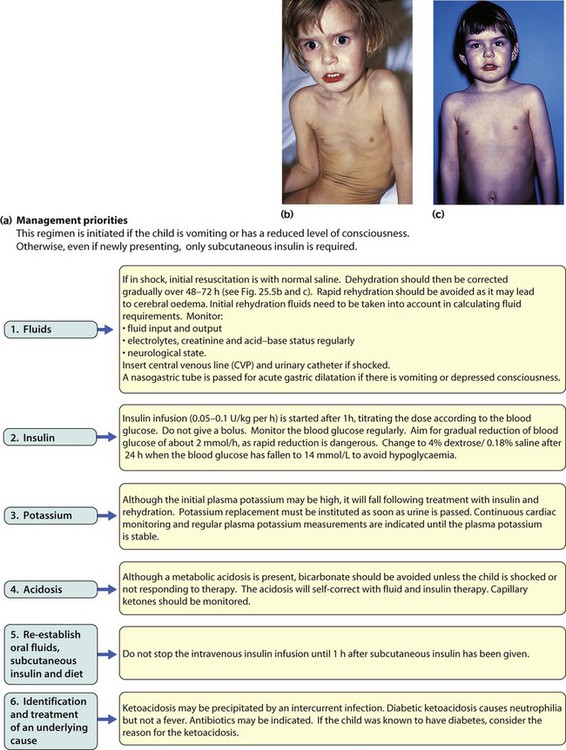

There are two peaks of presentation of type 1 diabetes, preschool and teenagers. It is also commoner to present in spring and autumn months. In contrast to adults, children usually present with only a few weeks of polyuria, excessive thirst (polydipsia) and weight loss; young children may also develop secondary nocturnal enuresis. Most children are diagnosed at this early stage of the illness (Box 25.2). Advanced diabetic ketoacidosis has become an uncommon presentation (<10% in some areas of the UK), but requires urgent recognition and treatment. Diabetic ketoacidosis may be misdiagnosed if the hyperventilation is mistaken for pneumonia or the abdominal pain for appendicitis or constipation.

Diagnosis

Type 2 diabetes should be suspected if there is a family history, in children from the Indian subcontinent and in severely obese children with signs of insulin resistance (acanthosis nigricans – velvety dark skin on the neck or armpits (Fig. 25.2), skin tags or the polycystic ovary phenotype in teenage girls).

Initial management of type 1 diabetes

As type 1 diabetes in childhood is uncommon (1–2 children per large secondary school), much of the initial and routine care is delivered by specialist teams (Box 25.3).

An intensive educational programme is needed for the parents and child, which covers:

• A basic understanding of the pathophysiology of diabetes

• Injection of insulin: technique and sites

• Diet: reduced refined carbohydrate; healthy diet with no more than 30% fat intake; ‘carbohydrate counting’, estimating the amount of carbohydrate in food to allow calculation of the insulin required for each meal or snack

• Adjustments of diet and insulin for exercise

• ‘Sick-day rules’ during illness to prevent ketoacidosis

• Blood glucose (finger prick) monitoring and blood ketones when unwell

• The recognition and staged treatment of hypoglycaemia

• Where to get advice 24 hours a day

• The help available from voluntary groups, e.g. local groups or ‘Diabetes UK’

• The psychological impact of a lifelong condition with potentially serious short- and long-term complications.

Insulin

• Human insulin analogues. Rapid-acting insulin analogues, e.g. insulin lispro, insulin glulisine or insulin aspart (trade names Humalog, Apidra and NovoRapid, respectively) – with a much faster onset and shorter duration of action than soluble regular insulin. There are also very long-acting insulin analogues, e.g. insulin detemir (Levemir) or glargine (Lantus)

• ‘Short-acting’ soluble human regular insulin. Onset of action (30–60 min), peak 2–4 h, duration up to 8 h. Given 15–30 min before meals. Trade named examples are Actrapid and Humulin S

• Intermediate-acting insulin. Onset 1–2 h, peak 4–12 h. Isophane insulin is insulin with protamine, e.g. Insulatard and Humulin I

• Predetermined preparations of mixed short- and intermediate-acting insulins with 25% or 30% rapid-acting components.

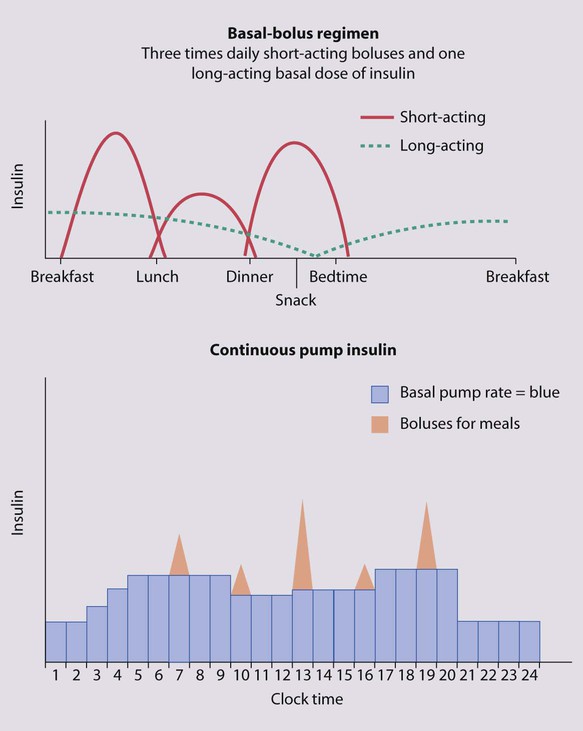

Most children are started on an insulin pump or a 3–4 times/day injection regimen (‘basal-bolus’) with short-acting insulin (e.g. Lispro, Glulisine or Insulin Aspart) being given (bolus) before each meal and snack plus long-acting insulin (e.g. Glargine or Detemir) in the late evening and/or before breakfast to provide insulin background (basal). These treatments both allow greater flexibility by relating the insulin more closely to food intake and exercise (Fig. 25.3). Patients and families are also taught how to correct any sugar above 10 mmol/L between usual meal times by extra short-acting insulin injections. However, the input required by the teams to start these intensive regimens is high, as is the need for a supportive school environment, and some patients and families still rely on twice-daily treatment with premixed insulin.

Diet

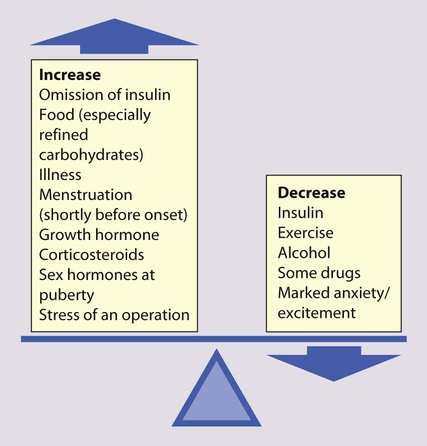

The diet and insulin regimen need to be matched (Fig. 25.4). The aim is to optimise metabolic control while maintaining normal growth. A healthy diet is recommended, with a high complex carbohydrate and relatively low fat content (<30% of total calories). The diet should be high in fibre, which will provide a sustained release of glucose, rather than refined carbohydrate, which causes rapid swings in glucose levels. ‘Carbohydrate counting’ allows patients to calculate their likely insulin requirements once their food choice for a meal is known, and taking into account their pre-meal sugar level and post-meal exercise pattern. Learning this balancing act requires a lot of educational input followed by refinement in the light of experience.

Long-term management

The aims of long-term management are:

• Normal growth and development

• Maintaining as normal a home and school life as possible

• Good diabetic control through knowledge and good technique

• Encouraging children to become self-reliant, but with adult supervision until they are able to take responsibility

• The prevention of long-term complications and an HbA1c of 58 mmol/mol (7.5%) or less.

These aims are difficult to achieve in all patients at all stages of their condition.

Problems in diabetic control

Good blood glucose control is particularly difficult in the following circumstances:

• Eating too many sugary foods, such as sweets taken at odd times, at parties or on the way home from school

• Infrequent or unreliable blood glucose testing. ‘Perfect’ results are often invented and written down just before clinic to please the diabetes team

• Illness – viral illnesses are common in the young and although it is usually stated that infections cause insulin requirements to increase, in practice the insulin dose required is variable, partly because of reduced food intake. The dose of insulin should be adjusted according to regular blood glucose monitoring. Insulin must be continued during times of illness and the urine or blood tested for ketones. If ketosis is increasing along with a rising blood sugar, the family should know how to seek immediate advice to ensure that they increase the soluble insulin dose appropriately or seek medical help for possible intravenous therapy

• Exercise – vigorous or prolonged planned exercise (cross-country running, long-distance hiking, skiing) requires reduction of the insulin dose and increase in dietary intake. Late hypoglycaemia may occur during the night or even the next day, but may be avoided by taking an extra bedtime snack, including slow-acting carbohydrate such as cereal or bread. Less vigorous exercise such as sports lessons in school and spontaneous outdoor play can be managed with an extra snack or a reduction in short-acting insulin before the exercise

• Eating disorders, which are common in young females with diabetes.

• Family disturbance such as divorce or separation

• Inadequate family motivation, support or understanding. As children can never have a ‘holiday’ from their diabetes, they need a great deal of encouragement to continuously maintain good control. Educational programmes for children and families need to be arranged regularly and matched to their current level of education. Special courses and holiday camps are available; in the UK they are organised by Diabetes UK and local groups.

Puberty and adolescence

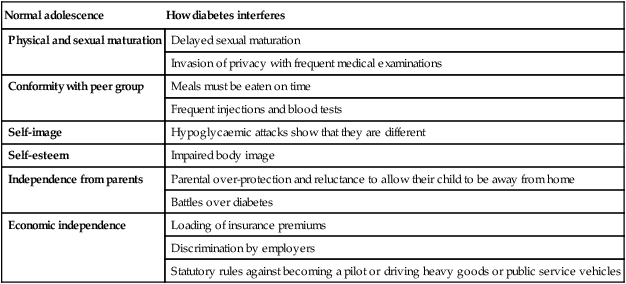

Battles with parents may concentrate on diabetic management instead of the more usual teenage concerns (Table 25.1). Conflict may also extend to involve the professionals of the diabetic team, because of intense anger against the disease which marks them out as different from their peers. Many parents are very protective at this time, whereas teenagers should be encouraged to take responsibility for their diabetes. Health education about smoking, alcohol and contraception may need to be provided. Liaison with a psychologist or child psychiatrist may be helpful. The professionals of the diabetic team may need to encourage diabetic teenagers to take better care of themselves. It is usually unhelpful to give lectures about the long-term risks to health, as these are likely to be seen as irrelevant by the teenagers. However, they may be helped if:

Table 25.1

How diabetes interferes with normal adolescence

| Normal adolescence | How diabetes interferes |

| Physical and sexual maturation | Delayed sexual maturation |

| Invasion of privacy with frequent medical examinations | |

| Conformity with peer group | Meals must be eaten on time |

| Frequent injections and blood tests | |

| Self-image | Hypoglycaemic attacks show that they are different |

| Self-esteem | Impaired body image |

| Independence from parents | Parental over-protection and reluctance to allow their child to be away from home |

| Battles over diabetes | |

| Economic independence | Loading of insurance premiums |

| Discrimination by employers | |

| Statutory rules against becoming a pilot or driving heavy goods or public service vehicles |

• There are clear short-term goals agreed by the patient

• Their efforts to improve their diabetic control, e.g. an improving or satisfactory HbA1c level, are communicated promptly and enthusiastically

• There is a united team approach, with agreement between professionals of the essentials they wish to promote and clear, unambiguous guidelines for health and diabetic management

• Peer group pressure is used to promote health. Activities such as holidays, etc., that allow teenagers to participate while learning about their diabetic management are encouraged. They may also benefit by being used as teachers of younger children.

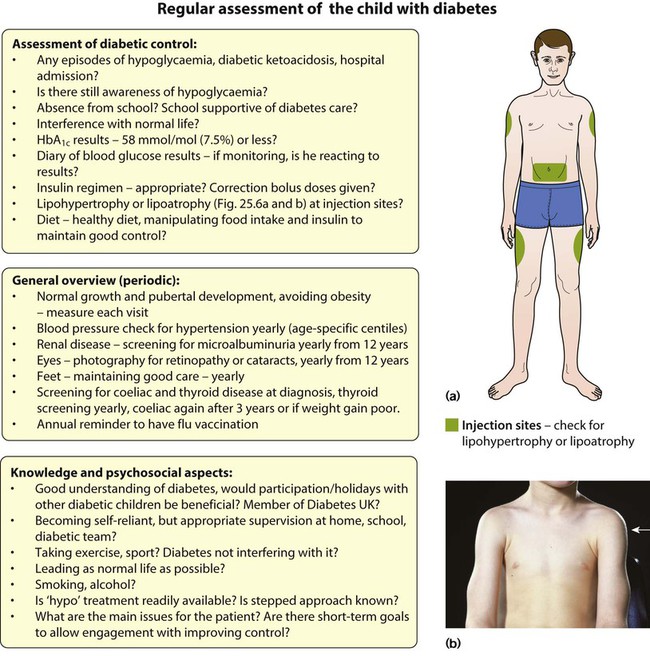

Prevention of long-term complications

• Growth and pubertal development. Some delay in the onset of puberty may occur. Obesity is common, especially in females, if their insulin dose is not reduced towards the end of puberty. Intensive insulin regimens increase the risk of excessive weight gain and BMI should be plotted at each clinic visit

• Blood pressure – must be checked at least once a year for evidence of hypertension

• Renal disease – the detection of microalbuminuria is an early sign of nephropathy and should be screened annually in teenagers

• Eyes – retinopathy or cataracts requiring treatment are rare in children but should be monitored annually after 5 years of diabetes or from the onset of puberty, ideally with retinal photography

• Feet – children should be encouraged to take good care of their feet from an early age, to avoid tight shoes and treat any infections early

• Other associated illnesses – coeliac disease and thyroid disease are more common in type 1 diabetes and easily missed clinically, so screening for them is recommended at diagnosis and subsequently (thyroid function yearly post-diagnosis and coeliac screening by tissue transglutaminase levels after 3 years) or if suspected clinically. There should be a low threshold for investigating for other autoimmune disorders (rheumatoid, vitiligo, etc.).

Hypoglycaemia

Hypoglycaemia is a common problem in neonates during the first few days of life (see Chapter 10). Thereafter, it is uncommon in non-diabetics. It is often defined as a plasma glucose <2.6 mmol/L, although the development of clinical features will depend on whether other energy substrates can be utilised. Clinical features include:

If the cause of the hypoglycaemia is unknown, it is vital that blood is collected at the time of the hypoglycaemia and the first available urine sent for analysis, so that a valuable opportunity for making the diagnosis is not missed (Box 25.5).

Hypothyroidism

Congenital hypothyroidism

Detection of congenital hypothyroidism is important, as it is:

• Relatively common, occurring in 1 in 4000 births

• One of the few preventable causes of severe learning difficulties.

Causes of congenital hypothyroidism are:

• Maldescent of the thyroid and athyrosis – the commonest cause of sporadic congenital hypothyroidism. In early fetal life, the thyroid migrates from a position at the base of the tongue (sublingual) to its normal site below the larynx. The thyroid may fail to develop completely or partially. In maldescent, the thyroid remains as a lingual mass or a unilobular small gland. The reason for this failure of formation or migration is not well understood

• Dyshormonogenesis, an inborn error of thyroid hormone synthesis, in about 5–10% of cases, although commoner in some ethnic groups with consanguineous marriage

• Iodine deficiency, the commonest cause of congenital hypothyroidism worldwide but rare in the UK. It can be prevented by iodination of salt in the diet

• Hypothyroidism due to TSH deficiency – isolated TSH deficiency is rare (<1% of cases) and is usually associated with panhypopituitarism, which usually manifests with growth hormone, gonadotrophin and ACTH deficiency leading to hypoglycaemia or micropenis and undescended testes in affected boys before the hypothyroidism becomes evident.

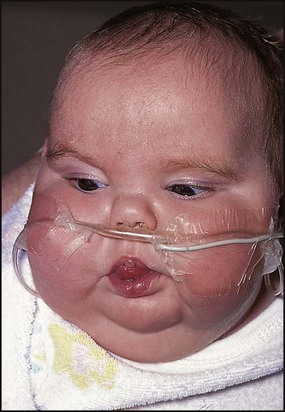

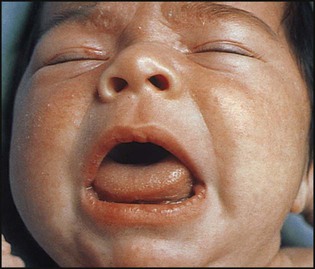

The clinical features (Box 25.7 and Fig. 25.7) are difficult to differentiate from normal in the first month of life, but become more prominent with age. There is a slight excess of other congenital abnormalities, especially heart defects.

Hyperthyroidism

This usually results from Graves disease (autoimmune thyroiditis), secondary to the production of thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins (TSIs). The clinical features are similar to those in adults, although eye signs are less common (Box 25.8 and Fig. 25.8). It is most often seen in teenage girls. The levels of thyroxine (T4) and/or tri-iodothyronine (T3) are elevated and TSH levels are suppressed to very low levels. Antithyroid peroxisomal antibodies may also be present which may eventually result in spontaneous resolution of the thyrotoxicosis but subsequently cause hypothyroidism (so-called hashitoxicosis).

Parathyroid disorders

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) promotes bone formation via bone-forming cells (osteoblasts). However, when calcium levels are low, PTH promotes bone resorption via osteoclasts, increases renal uptake of calcium and activates metabolism of vitamin D to promote gut absorption of calcium. In hypoparathyroidism, which is rare in childhood, in addition to a low serum calcium, there is a raised serum phosphate and a normal alkaline phosphatase. The parathyroid hormone level is very low. Severe hypocalcaemia leads to muscle spasm, fits, stridor and diarrhoea. It is a common problem in premature infants, and increasingly seen as a presentation of severe rickets (see Ch. 12). Other causes are rare in childhood.

Adrenal cortical insufficiency

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia is the commonest non-iatrogenic cause of insufficient cortisol and mineralocorticoid secretion (see Ch. 11).

Primary adrenal cortical insufficiency (Addison disease) is rare in children. It may result from:

• An autoimmune process, sometimes in association with other autoimmune endocrine disorders, e.g. diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism

• Haemorrhage/infarction – neonatal, meningococcal septicaemia (usually fatal)

• X-linked adrenoleucodystrophy, a rare neurodegenerative metabolic disorder

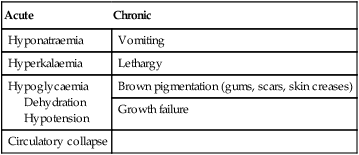

Presentation

Infants present acutely (Box 25.9) with a salt-losing crisis, hypotension and/or hypoglycaemia. Dehydration may follow a gastroenteritis-like illness, from which the child recovers until the next episode. In older children, presentation is usually with chronic ill health and pigmentation (Fig. 25.9).

Cushing syndrome

Glucocorticoid excess in children is usually a side-effect of long-term glucocorticoid treatment (intravenous, oral or, more rarely, inhaled, nasal or topical) for conditions such as the nephrotic syndrome, asthma or, in the past, for severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia (Box 25.10 and Fig. 25.10). Corticosteroids are potent growth suppressors and prolonged use in high dosage will lead to reduced adult height and osteopenia. This unwanted side-effect of systemic corticosteroids is markedly reduced by taking corticosteroid medication in the morning on alternate days.

Inborn errors of metabolism

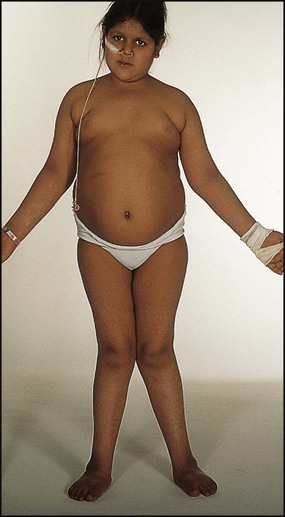

Presentation

After birth, inborn errors of metabolism usually, but not invariably, present in one of five ways:

• As a result of newborn screening, e.g. phenylketonuria (PKU), or family screening, e.g. familial hypercholesterolaemia

• After a short period of apparent normality, with a severe neonatal illness with poor feeding, vomiting, encephalopathy, acidosis, coma and death, e.g. organic acid or urea cycle disorders

• As an infant or older child with an illness similar to that described above but with hypoglycaemia as a prominent feature or as an ALTE (acute life-threatening episode) or near-miss ‘cot death’, e.g. a fat oxidation defect such as medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (MCADD)

• In a subacute way, after a period of normal development, with regression, organomegaly and coarse facies, e.g. mucopolysaccharide disease or other lysosomal storage disorder or with enlargement of the liver and/or spleen alone, with or without accompanying biochemical upset such as hypoglycaemia, e.g. glycogen storage disease

Disorders presenting acutely in the neonatal period

• Disorders of the catabolic pathways of several essential amino acids (the branched-chain amino acids, leucine, isoleucine and valine, and odd-chain amino acids, e.g. threonine) to cause maple syrup urine disease and other organic acid disorders

• A disorder of carbohydrate metabolism – classical galactosaemia.

• Vomiting, acidosis and circulatory disturbance, followed by depressed consciousness and convulsions – suggestive of one of the organic acidaemias

• Neurological features of lethargy, refusal to feed, hypotonia, drowsiness, unconsciousness and apnoea – suggestive of primary defects of the urea cycle. Improvement when given intravenous fluids but relapse if milk feeds are restarted is characteristic of classical galactosaemia.

Disorders of carbohydrate metabolism

Galactosaemia

This rare, recessively inherited disorder results from deficiency of the enzyme galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase, which is essential for galactose metabolism. When lactose-containing milk feeds such as breast or infant formula are introduced, affected infants feed poorly, vomit and develop jaundice and hepatomegaly and hepatic failure (see Ch. 20). Chronic liver disease, cataracts and developmental delay are inevitable if the condition is untreated. Management is with a lactose- and galactose-free diet for life. Even if treated early, there are usually moderate learning difficulties (adult IQ 60–80).

Glycogen storage disorders

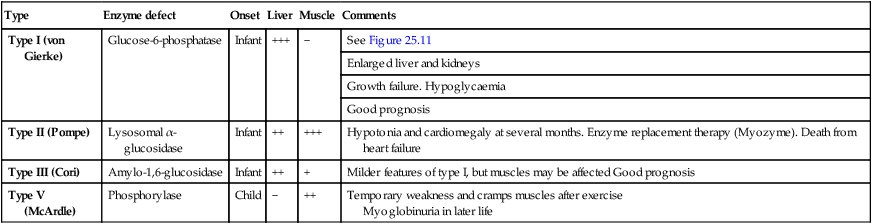

These mostly recessively inherited disorders have specific enzyme defects which prevent mobilisation of glucose from glycogen, resulting in an abnormal storage of glycogen in liver and/or muscle. There are nine main enzyme defects, some of which are shown in Table 25.2. The disorder may predominantly affect muscle (e.g. types II, V), leading to skeletal muscle weakness. In type II (Pompe disease) there is generalised intralysosomal storage of glycogen. The heart is severely affected, leading to death from cardiomyopathy. In other types (e.g. I, III) the liver is the main organ of storage, and hepatomegaly and hypoglycaemia are prominent (Fig. 25.11). Long-term complications of type I include hyperlipidaemia, hyperuricaemia, the development of hepatic adenomas and cardiovascular disease.

Table 25.2

Some of the glycogen storage disorders

| Type | Enzyme defect | Onset | Liver | Muscle | Comments |

| Type I (von Gierke) | Glucose-6-phosphatase | Infant | +++ | − | See Figure 25.11 |

| Enlarged liver and kidneys | |||||

| Growth failure. Hypoglycaemia | |||||

| Good prognosis | |||||

| Type II (Pompe) | Lysosomal α-glucosidase | Infant | ++ | +++ | Hypotonia and cardiomegaly at several months. Enzyme replacement therapy (Myozyme). Death from heart failure |

| Type III (Cori) | Amylo-1,6-glucosidase | Infant | ++ | + | Milder features of type I, but muscles may be affected Good prognosis |

| Type V (McArdle) | Phosphorylase | Child | − | ++ | Temporary weakness and cramps muscles after exercise Myoglobinuria in later life |

Hyperlipidaemia

Familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH)

This autosomal dominant disorder of lipoprotein metabolism is due to a defect in the LDL receptor. About 1 in 500 of the population are affected. The serum LDL cholesterol concentration is markedly raised (>3.3 mmol/L). The condition is associated with premature coronary heart disease, which occurs in half by 50 years of age in males and by 60 years in females. Skin and tendon xanthomata (Fig. 25.12) may be present, but are uncommon in childhood. Drug therapy is considered in children aged 10 years and older and depends on how high the LDL cholesterol concentration is raised, if there is a family history of premature coronary heart disease (<55 years of age), if there is evidence of tissue lipid deposition (xanthomata or bruits) and other non-lipid risk factors, e.g. diabetes. The main drugs used are the non-systemically acting bile acid sequestrants and more recently the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, the statins. Although bile acid sequestrants are moderately effective, compliance remains a major problem with them. Statins have been shown to be effective in children, without adverse effects on growth, maturation or endocrine function. The fibrate drug fenofibrate has also been shown to reduce LDL cholesterol and to be well tolerated by children and adolescents.