Chapter 384 Emphysema and Overinflation

Localized Obstructive Overinflation

When a ball-valve type of obstruction partially occludes the main stem bronchus, the entire lung becomes overinflated; individual lobes are affected when the obstruction is in lobar bronchi. Segments or subsegments are affected when their individual bronchi are blocked. Localized obstructions that can be responsible for overinflation include foreign bodies and the inflammatory reaction to them, abnormally thick mucus (cystic fibrosis, Chapter 395), endobronchial tuberculosis or tuberculosis of the tracheobronchial lymph nodes (Chapter 207), and endobronchial or mediastinal tumors. When most or all of a lobe is involved, the percussion note is hyperresonant over the area, and the breath sounds are decreased in intensity. The distended lung can extend across the mediastinum into the opposite hemithorax. Under fluoroscopic scrutiny during exhalation, the overinflated area does not decrease, and the heart and the mediastinum shift to the opposite side because the unobstructed lung empties normally.

Unilateral Hyperlucent Lung

Unilateral hyperlucent lung can be associated with a variety of cardiac and pulmonary diseases of children, but in some patients, it occurs without demonstrable underlying active disease. More than half the cases follow one or more episodes of pneumonia; a rising titer to adenovirus (Chapter 254) has been documented in several children. This condition can follow bronchiolitis obliterans and can include obliterative vasculitis as well, accounting for the greatly diminished perfusion and vascular marking on the affected side.

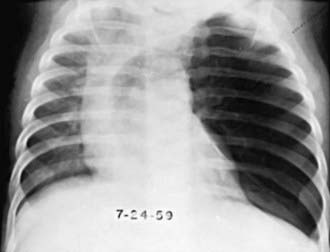

Congenital Lobar Emphysema

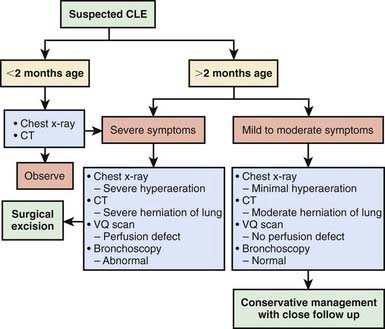

Clinical manifestations usually become apparent in the neonatal period but are delayed for as long as 5-6 mo in 5% of patients. Many cases are diagnosed by antenatal ultrasonography. Babies with prenatally diagnosed cases are not always symptomatic at birth. In some patients, CLE remains undiagnosed until school age or beyond. Signs range from mild tachypnea and wheeze to severe dyspnea with cyanosis. CLE can affect one or more lobes; it affects the upper and middle lobes, and the left upper lobe is the most common site. The affected lobe is essentially nonfunctional because of the overdistention, and atelectasis of the ipsilateral normal lung can ensue. With further distention, the mediastinum is shifted to the contralateral side, with impaired function seen as well (Fig. 384-1). A radiolucent lobe and a mediastinal shift are often revealed by radiographic examination. A CT scan can demonstrate the aberrant anatomy of the lesion, and MRI or MR angiography can demonstrate any vascular lesions, which might be causing extraluminal compression. Nuclear imaging studies are useful to demonstrate perfusion defects in the affected lobe. Figure 384-2 outlines evaluation of an infant presenting with suspected CLE. The differential diagnosis includes pneumonia with or without an effusion, pneumothorax, and cystic adenomatoid malformation.

Figure 384-2 Algorithm for evaluation and treatment of congenital lobar emphysema (CLE).

(Adapted from Senocak ME, Ciftci AO, et al: Congenital lobar emphysema: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations, J Pediatr Surg 34:1347–1351, 1999. Cited in Chao MC, Karamzadeh AM, Ahuja G: Congenital lobar emphysema: an otolaryngologic perspective, Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 69:553, 2005.)

Overinflation of All Three Lobes of the Right Lung

Overinflation of all three lobes of the right lung has been produced by anomalous location of the left pulmonary artery, which impinges on the right main stem bronchus. Hyperinflation also occurs in patients with the absent pulmonary valve type of tetralogy of Fallot (Chapter 424.1) and secondary aneurysmal dilatation of the pulmonary artery, which partially compresses the main stem bronchi. A number of neonates have lobar overinflation while being treated for hyaline membrane disease with assisted ventilation, suggesting an acquired cause. Medical management with selective intubation of the unaffected bronchus or high-frequency ventilation has occasionally been successful and lobectomy avoided.

Generalized Obstructive Overinflation

Pathology

In chronic overinflation, many of the alveoli are ruptured and communicate with one another, producing distended saccules. Air can also enter the interstitial tissue (i.e., interstitial emphysema), resulting in pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax (Chapters 405 and 406).

Diagnosis

Bullous Emphysema

Bullous emphysematous blebs or cysts (pneumatoceles) result from overdistention and rupture of alveoli during birth or shortly thereafter, or they may be sequelae of pneumonia and other infections. They have been observed in tuberculosis lesions during specific antibacterial therapy. These emphysematous areas presumably result from rupture of distended alveoli, forming a single or multiloculated cavity. The cysts can become large and might contain some fluid; an air-fluid level may be demonstrated on the radiograph (Fig. 384-3). The cysts should be differentiated from pulmonary abscesses. In most cases, the cysts disappear spontaneously within a few mo, although they can persist for a yr or more. Aspiration or surgery is not indicated except in cases of severe respiratory and cardiac compromise.

Chao MC, Karamzadeh AM, Ahuja G. Congenital lobar emphysema: an otolaryngologic perspective. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:549-554.

Cumming GR, Macpherson RI, Chernick V. Unilateral hyperlucent lung syndrome in children. J Pediatr. 1971;78:250-260.

Horak E, Bodner J, Gassner I, et al. Congenital cystic lung disease: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Clin Pediatr. 2003;42:251-261.

Karnak I, Senocak ME, Ciftci AO, et al. Congenital lobar emphysema: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1347-1351.

Kim CK, Koh JY, Han YS, et al. Swyer-James syndrome with finger clubbing after severe measles infection. Pediatr Int. 2008;50:413-415.

McKenzie SA, Allison DJ, Singh MP, et al. Unilateral hyperlucent lung: the case for investigation. Thorax. 1980;35:745-750.

Mei-Zahar M, Konen O, Manson D, et al. Is congenital lobar emphysema a surgical disease? J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1058-1061.

Mura M, Zompatori M, Mussoni A, et al. Bullous emphysema versus diffuse emphysema: a functional and radiologic comparison. Respir Med. 2005;99:171-178.

Ulku R, Onat S, Ozçelik C. Congenital lobar emphysema: differential diagnosis and therapeutic approach. Pediatr Int. 2008;50:658-661.

Wong KS, Liu HP, Cheng KS, et al. Pathological case of the month. Primary bullous emphysema with spontaneous pneumothorax. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:845-856.