Emotions and behaviour

Knowledge of children’s emotions and behaviour is important in order to:

Principles of normal development

Normal parenting

A child’s behaviour, emotional responses and personality are the end result of interplay between genetic predisposition and environmental influences. The environment provides experience from which stems knowledge, learned behaviour or emotional responses and attitudes to oneself and the world. Interpersonal relationships are major environmental factors in promoting psychosocial development and the child’s family is a principal source of these. Within the family, children should be protected, nurtured, educated and contained so that their development is supported optimally. Many societies are going through major demographic changes, including rising numbers of family breakdowns, lone-parent families and same gender parents. However, irrespective of the family structure, the essential elements of competent parenting or what is commonly referred to as ‘good-enough parenting’ are the same for all families (Box 23.1). Beyond this, the parents’ attitude towards their children and how they handle their individual children help to determine how their personalities develop.

Normal early relationships

• a particularly close relationship within which the child’s development of trust, empathy, conscience and ideals is promoted, forming a prototype for future close relationships

• the child’s primary source of comfort, providing the principal method of coping with stress (fear, anxiety, pain, etc.).

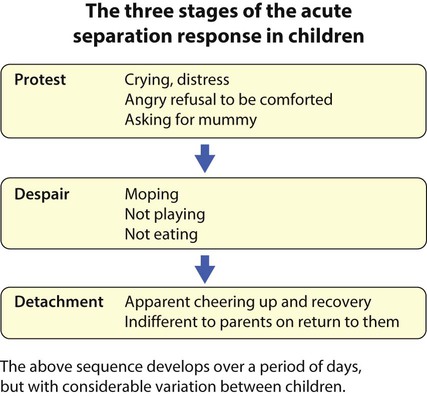

If a young child is placed in strange, impersonal surroundings and separated from the mother for more than several hours, a triphasic acute separation reaction may set in (Fig. 23.1):

• Mounting anxiety about the fact that the child’s mother fails to reappear produces distressed, irritable tearfulness (protest), which is hard to comfort

• After a day or two, this turns into a withdrawn state with no play, no interest in food and little speech or willingness for personal contact (despair)

• The child gradually cheers up from this but the close contact with the mother has been lost and the child is relatively indifferent to her when she reappears (detachment).

The selective clinging of early attachment behaviour diminishes over time so that in the second year of life children extend their emotional attachments to other family members and carers. By school age, they can tolerate separations from their parents for several hours. Children vary in their ability to do this depending on their temperament and social circumstances. For example, a child who is constitutionally apprehensive, who has an exceptionally anxious mother, or who has parents who threaten abandonment is likely to continue to cling to his/her mother for protection and comfort. A series of frightening events will tend to perpetuate clinging, which may persist well into middle childhood (age 5–12 years). This interferes with children’s capacity to learn how to cope with anxiety on their own (Fig. 23.2).

Temperament

A child born with a difficult temperament is prone to:

• predominantly negative moods – whinging, moaning, crying

• intense emotional reactions – screaming rather than whimpering, jumping for joy rather than smiling

• irregular biological functions – a lack of rhythm in sleeping, hunger or toileting

• negative initial responses to novel situations, e.g. pushing a new toy away

• protracted adjustment to new situations – taking weeks or months to settle into a new playgroup.

Cognitive style

As children grow older, their thinking style evolves from one that is concrete to one that is able to cope with abstract thought. Below the age of about 5 years, thought is fundamentally egocentric, with the child being at the centre of his world (Box 23.2). During middle childhood, the dominant mode of thought is practical and orderly but tied to immediate circumstances and specific experiences rather than hypothetical possibilities or metaphors. Not until the mid-teens does the adult style of abstract thought begin to appear.

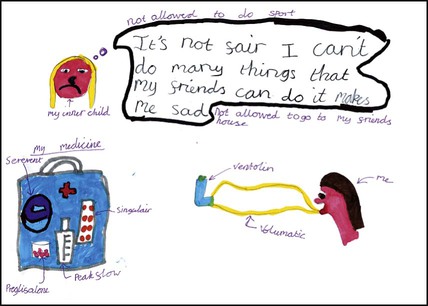

Coping with chronic or serious illness or adversities in childhood

Children can respond to adversity, including illness, in a number of ways:

• Cognitive response – can lie anywhere along the spectrum of over-acceptance to denial, with fluctuation over time. In over-acceptance, the child may allow the illness to overtake their life resulting in more impairment than is expected for level of symptoms, and high levels of anxiety about the slightest symptom. With denial, symptoms and warning signs may be ignored and treatment poorly adhered to.

• Emotional response – to diagnosis of illness and at times of relapse, may have similarities to a bereavement reaction or reaction to loss, with shock, denial, anger, followed by acceptance and adjustment (Fig. 23.3). Such responses to a serious illness are normal as long as the child proceeds through the phases.

• Behavioural response – young children tend to regress when stressed and behave younger than they actually are. A toddler may become overactive or clingy and display sleep and feeding difficulties. Regressive responses in older children predominantly manifest as problems with toileting, academic performance and peer relationships.

• Somatic response – can include expression of worry and distress through bodily symptoms such as recurrent abdominal pain.

• Nature of illness – this includes severity, chronicity, presence of constant discomfort and demands of treatment. Children with neurological disorders involving the brain, e.g. epilepsy, are at increased risk.

• Stage of illness – for example, diagnosis, deteriorations signalled by the need for new demanding treatments or by admissions to hospital.

• Age of the child – in infancy, illness may affect attachment and developmental milestones such as autonomy and mobility. Over 5 years of age there is a greater impact on educational progress, athletic activities and achievement. In adolescence, social adjustment, individual identity, independence from the family and poor adherence to treatment become more of an issue. Prolonged separation from parents resulting from illness will have a particularly negative impact between the age of 6 months and 3 years.

• Temperament – a child who is more adaptable to new situations will fare better. In contrast, a child who from early life has been difficult to soothe will fare worse

• Intellectual capacity – brighter children generally cope better.

• Family factors – the illness can have detrimental effects on the family and family difficulties can aggravate adaptation to illness.

Adversities in the family

• Angry discord between family members

• Parental mental ill health, especially maternal depression

• Divorce (Boxes 23.3 and 23.4) and bereavement

• Emotional rejection or unremitting criticism

• Use of violence, terror, threats of abandonment or excessive guilt as disciplinary devices

• Taunting or belittlement of the child

• Inconsistent, unpredictable discipline

• Using the child to fulfil the unreasonable personal emotional needs of a parent

• Inappropriate responsibilities or expectations for the child’s level of maturity.

Problems of the preschool years

Meal refusal

An account of what goes on at a typical mealtime may reveal:

Most importantly, how much does the child eat between meals? A well-nourished child is getting food from somewhere. Not all parents regard sweets and crisps as being food. Some mothers, while concerned about their child’s apparently poor food intake, provide little variety in the child’s diet. For strategies for dealing with meal refusal, see Box 23.5. Children with faltering growth may require specialist referral if they do not respond to this advice.

Sleep-related problems

Difficulty in settling to sleep at bedtime

This is a common problem in the toddler years. The child will not go to sleep unless the parent is present. Most instances are normal expressions of separation anxiety, but there may be other obvious reasons for it which can be explored in taking a history (Box 23.6), supplemented if necessary by the parents keeping a prospective sleep diary. Many cases will respond to simple advice:

• Creating a bedtime routine which cues the child to what is required

• Telling the child to lie quietly in bed until he/she falls asleep, recognising that children cannot fall asleep to order (although that is what everyone tells them to do).

Disobedience, defiance and tantrums

Normal toddlers often go through a phase of refusing to comply with parents’ demands, sometimes angrily (‘the terrible 2s’). This is an understandable reaction to the discovery that the world is not organised around them. They also become confused and angered by the fact that the parent who provides them with comfort when they are distressed is also the person who is making them do things they do not wish to do. This seems exceptionally unfair to them. That is one reason why children play their parents up but may be fine with others. All this can exhaust and demoralise parents, not least because many people offer advice or criticism (everyone thinks themselves an expert in the area of children’s development and behaviour). The points listed in Box 23.7 can be made.

Temper tantrums are ordinary responses to frustration, especially at not being allowed to have or do something. They are common and normal in young preschool children. If asked for advice, a sensible first move is to take a history, analysing a couple of tantrums according to the ABC paradigm (Box 23.8). Next, examine the child to identify potential medical or psychological factors. Medical factors include global or language delay, hearing impairment (e.g. glue ear) and medication with bronchodilators or anticonvulsants. If none are present, there are management strategies that can be adopted, some of which are shown in Box 23.9.

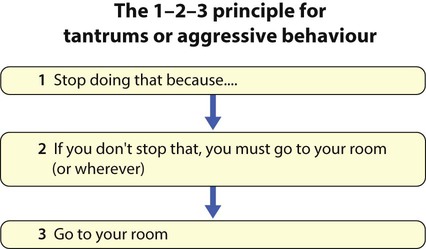

Aggressive behaviour

Small children can be aggressive for a host of reasons, ranging from spite to exuberance. Much aggressive behaviour is learned, either by being rewarded (often inadvertently) or by copying parents, siblings or peers. For example, many instances of aggressive, demanding behaviour are provoked or intensified by a parent shouting at or hitting their child. In such cases, it is the parent’s behaviour which needs to change. In most instances, the same principles as apply to tantrums are valid: make rules clear, stick to them, keep cool, do not give in and use time out if necessary. The latter can often be used on a 1–2–3 principle (Fig. 23.4). A tired or stressed child will be irritable and prone to angry outbursts, as will children whose communication skills are compromised by deafness or a developmental language disorder so that they are frustrated and exasperated. Optimistic reassurance that the child will spontaneously grow out of a pattern of aggressive behaviour is mistaken; once established, an aggressive behavioural style is remarkably persistent over a period of years. Thus, aggressive behaviour in children needs to be proactively managed. There are several evidence-based parenting programmes that are effective for teaching parents to manage aggression in their children. Parents should be encouraged to attend such programmes.

Problems of middle childhood

Nocturnal enuresis

Organic causes of enuresis are uncommon but include:

• Faecal retention severe enough to reduce bladder volume and cause bladder neck dysfunction

• Polyuria from osmotic diuresis, e.g. diabetes mellitus, or renal concentrating disorders, e.g. chronic renal failure.

A urine sample should always be tested for glucose and protein and checked for infection. Daytime and secondary enuresis are considered in Chapter 18.

Faecal soiling

• Constipation, possibly following dehydration during an illness

• Inhibition of defecation because of pain from a fissure

A stool softener (macrogol) is given for a couple of weeks, followed, if necessary, by a stimulant laxative (docusate, sodium picosulphate or senna) and an osmotic laxative (lactulose). Sometimes an enema is required. Once the rectum is disimpacted, maintenance laxative therapy is maintained (see Fig. 13.14 for details). The child can be encouraged to defecate regularly in the toilet, which earns stars on a star chart. Such retraining may take a number of weeks while the distended rectum shrinks to a normal size. Throughout this period a regular laxative is usually needed. The stars may therefore need to be cashed in for tangible rewards such as extra pocket money in order to maintain the incentive.

Recurrent unexplained somatic symptoms/somatisation

Recurrent central abdominal pain, often sharp and colicky, affects about 10% of school-age children. The causes are considered in Chapter 13. In the majority of cases, no organic cause can be objectively demonstrated, yet the child is obviously in pain. Some will have an emotional cause for their pain, but in many, no aetiology, medical or psychiatric, can be demonstrated.

Antisocial behaviour

Children steal, lie, disobey, light fires, destroy things and pick fights for various reasons:

• Failure to learn when to exercise social restraint

• Lack of social skills, such as the ability to negotiate a disagreement

• They may be responding to the challenges of their peers in spite of their parents’ prohibitions

• They may be chronically angry and resentful

• They may find their own notions of good behaviour overwhelmed by emotion such as sadness or temptation.

Educational underachievement

Children who achieve less well in school than expected are sometimes brought to doctors. It is important to evaluate parents’ and teachers’ expectations and ensure the child is actually able to rise to them. The services of an educational psychologist are indispensable. Core medical responsibilities include testing sight and hearing and attempting to elicit the cause of underachievement according to the list in Box 23.11. The topic is considered further in Chapter 4.

Adolescence

Cognitive style

The style of thought specifically associated with adolescence is formal operational (abstract) thought (Box 23.12), but this is acquired at various ages by different individuals during the teenage years, and a substantial minority do not develop it at all. Doctors are at a disadvantage here, as they have been selected by a series of examinations for excellence of their ability to manipulate abstractions and compare hypothetical predictions; they have often forgotten what it is like to think otherwise and communicate poorly with patients who still think concretely and practically (school-age children, about half of all teenagers and perhaps 1 in 5 adults). When interviewing adolescents, the skill is to avoid being patronising, while being sensitive as to whether abstract and reflective thought is solidly achieved. Using practical examples (not metaphors) and checking whether you have been understood will help to avoid the common problem of being faced with an adolescent who responds to questions with a sullen ‘don’t know’. This is considered further in Chapter 28.

Anorexia nervosa

• Self-induced weight loss resulting in a low body mass index (BMI); in children this needs to be plotted on a BMI centile chart, in older adolescents it is ≤17.5 kg/m2

• A distorted perception of her body, which increases with weight loss

• A determined attempt to lose weight or avoid weight gain, by either restricting food intake, self-induced vomiting, laxative abuse, excessive exercising or using a combination of these methods

• When body weight falls below a critical point, pubertal development is halted and reversed so that menstruation ceases and the girl effectively becomes a prepubertal child. This may spare her some of the challenges of adolescence, particularly those related to sexuality

• The discovery by a girl who has felt powerless that through self-starvation she can control her shape and development and thus increase her sense of self-worth and self-effectiveness

• Preoccupations and dreams of food and cooking which come to dominate mental life as a response to starvation. There ensues a tremendous mental struggle not to give in and eat, which assumes prime importance in the girl’s mental life

• The dramatic and visible effects of self-starvation on the girl, which can unite some parents in caring for their daughter and save a discordant marriage from divorce, something which she may fear is imminent.

Depression

Low mood can arise secondary to adverse circumstances or sometimes spontaneously. Depression as a clinical condition is more than sadness and misery; it extends to affect motivation, judgement, the ability to experience pleasure and provokes emotions of guilt and despair. It may disturb sleep, appetite and weight. It leads to social withdrawal, an important sign. Such a state is well recognised among adolescents, particularly girls, but occasionally affects prepubertal children. The general picture is comparable to depression in adults but there are differences (Box 23.13).

Psychosis

• Schizophrenia, where no specific medical cause is identified and there is generally no major disturbance of mood other than blunting or flattening of affect

• Bipolar affective disorder, where the psychosis is associated with lowered mood as in depression or elevation in mood as in mania

• Organic psychosis occurs in delirium, substance-induced disorders and dementia.

Management of emotional and behavioural problems

With this in mind, it is possible to talk about the three Ps of causation:

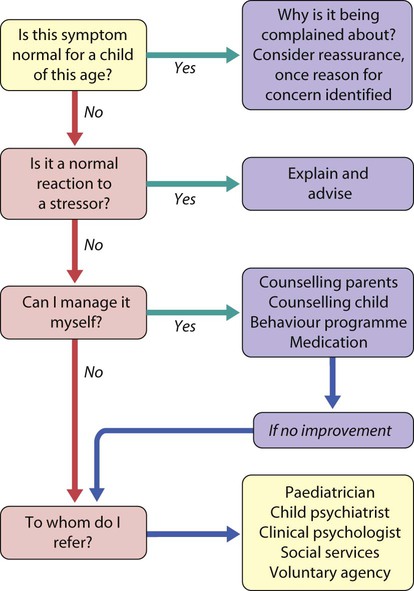

Treatment

Figure 23.5 shows an approach to managing a child displaying an emotional or behavioural problem. The process of making a referral to a child and adolescent mental health service (CAMHS) is most likely to succeed if the referrer has already taken some of the history and engaged the parents and child in an attempt to alleviate the problem. Many doctors, general practitioners and paediatricians in particular, are good generalists in child mental health issues and the mental health specialist should be seen as a specialist extension of their expertise, rather than a completely different sort of person.

In general, the management of children’s emotional and behavioural problems:

• should be psychological rather than pharmacological

• does not need the child to be admitted to hospital (unless required as a place of safety for suicidal children or for child protection)

• involves parents as key participants

• may involve a variety of health and social service professionals.

Often more than one intervention is required and treatments are combined and several professionals become involved. The main treatment interventions employed are described in Box 23.15.