115 Emergency Renal Ultrasonography

• The presence of unilateral hydronephrosis in the correct clinical context is used as an indirect finding for the diagnosis of renal colic. Obstructing stones are not typically visualized directly during bedside sonography.

• Identification of hydronephrosis in one kidney should prompt evaluation of the contralateral side to rule out bilateral hydronephrosis as a result of bladder outlet obstruction.

• Ultrasound measurements of the urinary bladder can be used to estimate bladder volume and identify a distended bladder in patients with suspected urinary retention.

• Abdominal aortic aneurysm should always be included in the differential diagnosis of renal colic. Emergency practitioners should maintain a low threshold for performing screening ultrasound of the aorta in patients with risk factors for an aneurysm.

Evidence-Based Review

Computed tomography (CT) currently has the greatest sensitivity and specificity of imaging modalities used for the diagnosis of renal colic. When compared with ultrasound, non–contrast-enhanced CT is more sensitive in identifying obstructing ureteral stones1–4 and more accurate in measuring stone size.4,5 CT also more consistently locates the specific site of obstruction along the course of the ureter and can identify other causes of abdominal pain that may mimic acute renal colic.

However, routine use of CT for suspected renal colic has significant limitations. Patients are exposed to significant amounts of ionizing radiation when they undergo CT of the abdomen and pelvis,6,7 which makes CT inadvisable during pregnancy and less appealing in the pediatric population. Because renal colic is a recurrent diagnosis, patients may eventually receive multiple CT scans over time, and cumulative radiation doses may rise to concerning levels8 and place patients at risk for cancer later in life. Additionally, radiologic imaging has been shown to be the largest contributor to the cost of hospitalization in patients with renal colic, with CT being the most expensive imaging modality.9,10

Ultrasound offers a safe, noninvasive means of assessing for renal colic that does not subject the patient to any ionizing radiation. Traditionally, ultrasound has been thought to have only fair sensitivity (37% to 64%) for detecting stones and better sensitivity (74% to 85%) for the diagnosis of acute obstruction,1 whereas CT has consistently shown sensitivity greater than 90% for the diagnosis of ureteral stones.1–4 Recent studies using modern ultrasound equipment in the hands of skilled operators have demonstrated comparable sensitivity (76% to 98%) of ultrasound for the detection of ureteral stones.11–14 Although specific stone location and size cannot always be determined with ultrasound, surrogate findings may have prognostic value in guiding patient management. One study showed that normal renal ultrasound findings in the setting of suspected renal colic predicted a very low risk (0.6%) for subsequent urologic intervention.15

The goal of bedside ultrasound is to identify unilateral hydronephrosis as an indirect sign of obstructing ureteral stones. In the emergency department setting, Rosen et al. demonstrated a sensitivity of 72% and specificity of 73% for the detection of hydronephrosis with bedside ultrasound.16 More recently, Gaspari and Horst reported a sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 85% for the diagnosis of hydronephrosis.17 These results are comparable to a sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 92% for bedside ultrasound performed by on-call urologists; however, this study evaluated other renal findings in addition to hydronephrosis.18 Although the specific size of the obstructing stone is not typically demonstrated on bedside ultrasound, the degree of hydronephrosis may correlate with the size of the obstructing stone. A 2010 study showed that no or mild hydronephrosis predicted smaller stone size (<5 mm) as opposed to moderate or severe hydronephrosis.19

Bedside ultrasound for the measurement of urinary bladder volume has been well described in the literature. Bedside ultrasound provides a quantitative assessment of bladder volume when evaluating for urinary retention in the emergency department setting and can guide the need for emergency catheterization.20,21 Many studies have shown good correlation between sonographic bladder volume calculations and urine volumes obtained via catheterization.22–24 In the pediatric population, ultrasound has been shown to predict patients with volumes sufficient for successful catheterization of urine samples (>3 mL).25–28 This may help avoid multiple attempts at urinary catheterization, which can result in unnecessary patient discomfort and the potential for iatrogenic infection. Additionally, bedside ultrasound has demonstrated increased success rates during attempts at suprapubic aspiration when compared with traditional, landmark-based techniques.29–31

How to Scan

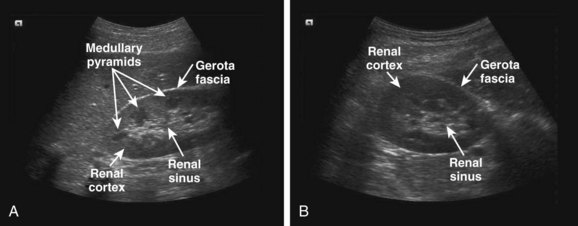

For the right kidney, the probe is initially placed along the lower portion of the rib cage in the midaxillary line with the probe marker directed toward the patient’s head. The resulting coronal view is the traditional right upper quadrant view of the focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination. The kidney lies in a plane oblique to the long axis of the body, and the probe usually needs to be rotated slightly counterclockwise to obtain a maximally longitudinal view of the kidney (Fig. 115.1, A). This orientation also helps the ultrasound transducer align the image in between the ribs, thus minimizing rib shadows. The transducer should then be angled anterior to posterior so that it fans through the entire kidney. To obtain a transverse view of the kidney, the probe is rotated 90 degrees in a counterclockwise direction (Fig. 115.1, B). The transducer should then be fanned superior to inferior to image the entire kidney in the transverse plane.

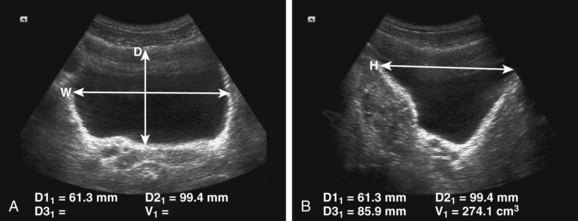

When measuring urinary bladder volume, the bladder should first be imaged in the transverse plane at the level where the largest view of the bladder is obtained. The image is frozen, and bladder depth and width are measured (Fig. 115.2, A). The bladder is then imaged in the sagittal plane, again at the level where the largest view of the bladder is obtained. The image is frozen, and bladder height is measured (Fig. 115.2, B). Bladder volume can be estimated with the simplified formula 0.75 × depth × width × height.20–22 On many ultrasound machines, software will automatically calculate bladder volume by using measurements obtained by the sonographer.

Images—Normal and Abnormal

The kidneys are paired, bean-shaped retroperitoneal structures that lie slightly oblique to the long axis of the body. A normal kidney measures 9 to 12 cm in length and is between 4 and 5 cm in width. A difference of up to 2 cm in measurements between the right and left kidney is considered within the normal range. On longitudinal images, the kidney will appear oval in shape (see Fig. 115.1, A); on transverse images, the kidney will appear circular (see Fig. 115.1, B).

The kidneys consist of a renal cortex, medullary pyramids, and renal sinus (see Fig. 115.1). The renal cortex has a homogeneous sonographic appearance and is slightly less echogenic than normal liver and spleen. The medullary pyramids may or may not be well visualized on bedside sonography. They appear as multiple hypoechoic cone-shaped structures between the renal sinus and cortex, with their apices directed toward the renal sinus. The renal sinus appears hyperechoic because of its fibrous and fatty tissue content. The renal collecting system, which consists of the renal pelvis and multiple calices, resides within the renal sinus. The kidney is surrounded by a hyperechoic fibrous capsule (Gerota fascia), as well as perinephric fat.

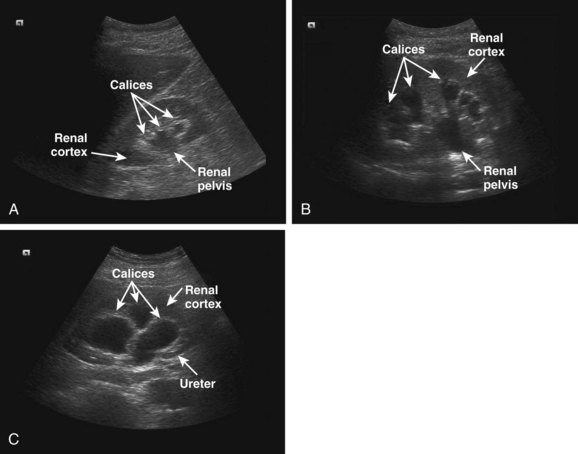

Hydronephrosis is manifested as varying degrees of dilation of the collecting system as a result of distal obstruction. It is best visualized on longitudinal images of the kidney. Hydronephrosis may be graded as mild, moderate, or severe. Mild hydronephrosis is defined as dilation of the renal pelvis and blunting of the normally concave renal calices. Anechoic areas will appear in the normally hyperechoic renal sinus as fluid fills and distends the renal pelvis (Fig. 115.3, A). Mild hydronephrosis may be difficult to appreciate on bedside ultrasound. Careful comparison with the contralateral kidney can help reveal more subtle cases of unilateral hydronephrosis. Prominent renal vessels within the renal sinus may be mistaken for mild hydronephrosis. Application of color flow or power Doppler can help differentiate whether an anechoic space within the renal sinus is due to blood vessels or actual dilation of the renal pelvis. Moderate hydronephrosis is defined as more prominent dilation of the renal pelvis and rounding of the renal calices (Fig. 115.3, B). Severe hydronephrosis is defined as extreme calyceal distention causing thinning of the renal cortex (Fig. 115.3, C). When chronic, hydronephrosis can result in a marked degree of cortical atrophy. In the setting of acute obstruction, calyceal rupture may occur and result in a urinoma. A urinoma appears as a stripe of anechoic free fluid surrounding a portion of the kidney.

Kidney stones appear as brightly echogenic structures and will exhibit posterior acoustic shadowing when sufficient size has been attained.3,5 Obstructing ureteral stones are not typically visualized directly during bedside ultrasonography. Nonobstructing stones within the renal pelvis are more frequently visualized, although they may be hard to distinguish from adjacent hyperechoic fibrofatty tissue within the renal sinus. Obstructing stones may occasionally be visualized at the ureteropelvic or ureterovesical junction. Obstructing stones within the remainder of the ureter are more challenging to identify because of overlying bowel gas. The ureters themselves are not discernible during bedside ultrasonography unless significantly dilated.

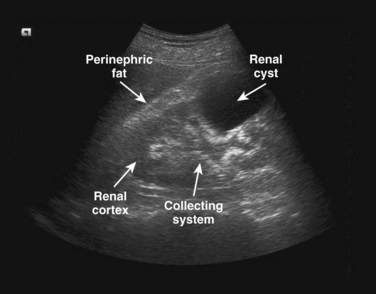

Renal cysts appear as rounded anechoic structures with thin, smooth walls and exhibit posterior acoustic enhancement (Fig. 115.4). Though not a primary indication for performing emergency renal sonography, renal cysts are not an uncommon finding and occur in roughly 50% of patients 50 years or older.32 When internal echoes, septations, or thick walls are visualized, other diagnoses, such as a hemorrhagic cyst, renal abscess, or carcinoma, are more likely. Making these diagnoses is outside the scope of bedside ultrasonography, and such findings should prompt comprehensive radiologic imaging. Additionally, any structure that distorts the normal renal architecture is concerning for malignancy. Renal cancers and pseudoaneurysms may have an appearance similar to simple renal cysts,33 and it is recommended that color flow or power Doppler be applied to evaluate for internal blood flow within any cystic structure seen in the kidneys.

How to Incorporate into Practice

Ultrasound serves as a valuable initial screening examination in patients suspected of having renal colic. It can be performed directly at the bedside by the emergency physician to rapidly categorize the likelihood of an obstructing ureteral stone. Though not specifically studied in the setting of renal colic, bedside ultrasound has been shown to expedite patient care and decrease length of stay in the emergency department when performing other focused studies.34,35 Bedside ultrasound may also speed the identification of life-threatening conditions such as a leaking AAA when being considered in the differential diagnosis.36

In patients with clinical findings suggestive of renal colic, especially in those with microscopic or gross hematuria, the presence of unilateral hydronephrosis may be adequate evidence of a ureteral stone. If findings on the initial bedside ultrasound are normal, it may be repeated after a period of hydration, which can subsequently reveal hydronephrosis. When mild to moderate hydronephrosis is identified as a surrogate for an obstructing ureteral stone, the patient may undergo standard treatment of renal colic. When severe hydronephrosis is seen as a new finding, comprehensive imaging by radiology and urgent urologic consultation are advised.20,21

Bedside ultrasound serves as a straightforward examination for the presence of a distended bladder when urinary retention is clinically suspected. A grossly enlarged bladder after the patient attempts to void indicates the need for urinary catheterization. In contrast, a collapsed bladder in the setting of suspected urinary retention should prompt a search for alternative diagnoses. Intermediate bladder sizes necessitate calculation of bladder volume with sonographic measurements. Although threshold values for what constitutes an elevated postvoid residual urine volume are poorly defined,37 a volume greater than 100 mL in the setting of symptoms of obstruction (urgency, frequency, hesitancy, decreased flow) is generally used as the lower threshold for acute urinary retention.38 It is important to remember that urinary retention, especially when prolonged, may lead to bilateral hydronephrosis, and ultrasound evaluation of the kidneys should reflexively follow identification of a distended bladder.

In the pediatric population, bedside ultrasound may guide the timing of urinary catheterization. Attempts at catheterization are unsuccessful in obtaining urine from pediatric patients approximately 25% of the time.25–27 A brief ultrasound evaluation of the bladder identifies patients with urine volumes adequate for collecting a urine sample via catheterization. A transverse bladder dimension larger than 2 cm and a sonographic bladder volume calculation of greater than 3 mL both predict successful urinary catheterization.25–27 In cases in which suprapubic bladder aspiration is indicated to obtain a urine sample, ultrasound provides procedural guidance and increases the rate of successful bladder taps.29–31

1 Lin EP, Bhatt S, Dogra VS, et al. Sonography of urolithiasis and hydronephrosis. Ultrasound Clin. 2007;2:1–16.

2 Sheafor DH, Hertzberg BS, Freed KS, et al. Nonenhanced helical CT and US in the emergency evaluation of patients with renal colic: prospective comparison. Radiology. 2000;217:792–797.

3 Catalano O, Nunziata A, Altei F, et al. Suspected ureteral colic: primary helical CT versus selective helical CT after unenhanced radiography and sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:379–387.

4 Fowler KA, Locken JA, Duchesne JH, et al. US for detecting renal calculi with nonenhanced CT as a reference standard. Radiology. 2002;222:109–113.

5 Ray AA, Ghiculete D, Pace KT, et al. Limitations to ultrasound in the detection and measurement of urinary tract calculi. Urology. 2010;76:295–300.

6 Denton ER, Mackenzie A, Greenwell T, et al. Unenhanced helical CT for renal colic—is the radiation dose justifiable? Clin Radiol. 1999;55:444–447.

7 Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2277–2284.

8 Katz SI, Saluja S, Brink JA, et al. Radiation dose associated with unenhanced CT for suspected renal colic: impact of repetitive studies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:1120–1124.

9 Turkcuer I, Serinken M, Karcioglu O, et al. Hospital cost analysis of management of patients with renal colic in the emergency department. Urol Res. 2010;38:29–33.

10 Grisi G, Stacul F, Cuttin R, et al. Cost analysis of different protocols for imaging a patient with acute flank pain. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1620–1627.

11 Patlas M, Farkas A, Fisher D, et al. Ultrasound vs CT for the detection of ureteric stones in patients with renal colic. Br J Radiol. 2001;74:901–904.

12 Ripolles T, Agramunt M, Errando J, et al. Suspected ureteral colic: plain film and sonography vs unenhanced helical CT. A prospective study in 66 patients. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:129–136.

13 Park SJ, Yi BH, Lee HK, et al. Evaluation of patients with suspected ureteral calculi using sonography as an initial diagnostic tool. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:1441–1450.

14 Passerotti C, Chow JS, Silva A, et al. Ultrasound versus computerized tomography for evaluating urolithiasis. J Urol. 2009;182:1829–1834.

15 Edmonds ML, Yan JW, Sedran RJ, et al. The utility of renal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of renal colic in emergency department patients. CJEM. 2010;12:201–206.

16 Rosen CL, Brown DF, Sagarin MJ, et al. Ultrasonography by emergency physicians in patients with suspected ureteral colic. J Emerg Med. 1998;16:865–870.

17 Gaspari RJ, Horst K. Emergency ultrasound and urinalysis in the evaluation of flank pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1180–1184.

18 Surange RS, Jeygopal NS, Chowdhury SD, et al. Bedside ultrasound: a useful tool for the on-call urologist? Int Urol Nephrol. 2001;32:591–596.

19 Goertz JK, Lotterman S. Can the degree of hydronephrosis on ultrasound depict kidney stone size? Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:813–816.

20 Ma OJ, Mateer JR, Blaivas M. Emergency ultrasound. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

21 Noble VE, Nelson B, Sutingco AN. Manual of emergency and critical care ultrasound. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

22 Bih LI, Ho CC, Tsai SJ, et al. Bladder shape impact on the accuracy of ultrasonic estimation of bladder volume. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:1553–1556.

23 Byun SS, Kim HH, Lee E, et al. Accuracy of bladder volume determinations by ultrasonography: are they accurate over entire bladder volume range? Urology. 2003;62:656–660.

24 Roerhrborn CG, Peters PC. Can abdominal ultrasound estimation of postvoiding residual (PVR) replace catheterization? Urology. 1988;31:445–449.

25 Chen L, Hsiao AL, Moore CL, et al. Utility of bedside bladder ultrasound before urethral catheterization in young children. Pediatrics. 2005;115:108–111.

26 Witt M, Baumann BM, McCans K. Bladder ultrasound increases catheterization success in pediatric patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:371–374.

27 Baumann BM, McCans K, Stahmer SA, et al. Volumetric bladder ultrasound performed by trained nurses increases catheterization success in pediatric patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:18–23.

28 Milling TJ, Amerongen RV, Melville L, et al. Use of ultrasonography to identify infants in whom urinary catheterization will be unsuccessful because of insufficient urine volume: validation of the urinary bladder index. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:510–513.

29 Chu RW, Wong YC, Luk SH, et al. Comparing suprapubic urine aspiration under real-time ultrasound guidance with conventional blind aspiration. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91:512–516.

30 Kiernan SC, Pinckert TL, Keszler M. Ultrasound guidance of suprapubic bladder aspiration in neonates. J Pediatr. 1993;123:189–191.

31 Gochman RF, Karasic RB, Heller MB. Use of portable ultrasound to assist urine collection by suprapubic aspiration. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20:631–635.

32 Middleton WD, Kurtz AB, Hertzberg BS. Ultrasound: the requisites, 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2004.

33 Mandavia DP, Pregerson B, Henderson SO. Ultrasonography of flank pain in the emergency department: renal cell carcinoma as a diagnostic concern. J Emerg Med. 2000;18:83–86.

34 Blaivas M, Sierzenski P, Plecque D, et al. Do emergency physicians save time when locating a live intrauterine pregnancy with bedside ultrasonography? Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:988–993.

35 Blaivas M, Harwood RA, Lambert MJ. Decreasing length of stay with emergency ultrasound examination of the gallbladder. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:1020–1023.

36 Plummer D, Clinton J, Matthew B. Emergency department ultrasound improves time to diagnosis and survival of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:417.

37 Kaplan SA, Wein AJ, Staskin DR, et al. Urinary retention and post-void residual urine in men: separating truth from tradition. J Urol. 2008;180:47–54.

38 Kelly CE. Evaluation of voiding dysfunction and measurement of bladder volume. Rev Urol. 2004;6:S32–S37.