Emergency Dental Procedures

Teeth

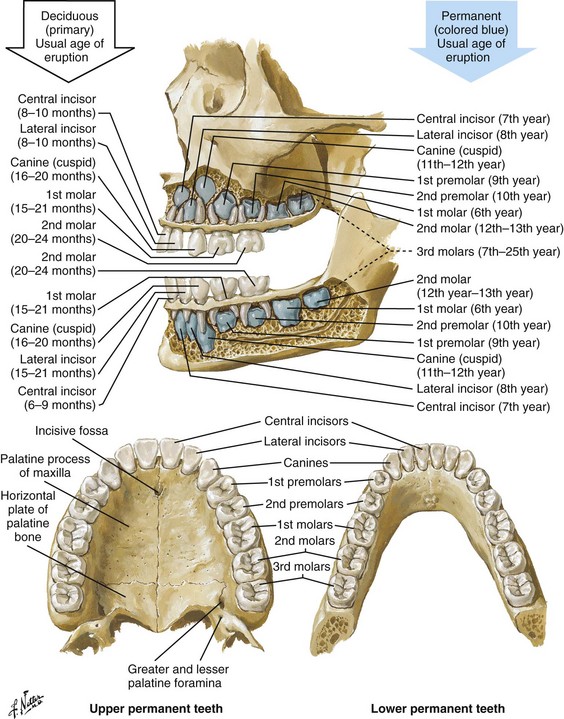

The adult dentition normally consists of 32 teeth: 8 incisors, 4 canines, 8 premolars, and 12 molars. From the midline to the back of the mouth on each side, there is a central incisor, a lateral incisor, a canine, two premolars (bicuspids), and three molars, the last of which is the wisdom tooth (Fig. 64-1). The 20 primary or deciduous (baby) teeth include 8 incisors, 4 canines, and 8 molars. From the midline to the back of the mouth, there is a central incisor, a lateral incisor, a canine, and two molars (Fig. 64-2). Agenesis, or lack of proper formation of a tooth or teeth, is not uncommon, especially in the maxilla. Likewise, supernumerary, or extra, teeth may also occur. The adult teeth are numbered from 1 to 32, with the first tooth being the right upper third molar and the 16th tooth being the left upper third molar. The left lower third molar is the 17th, and the 32nd tooth is the right lower third molar. Numerous classification and numbering systems of the teeth exist; however, it is probably best for clinicians to simply describe the location and type of tooth in question (e.g., upper left second premolar, lower right canine). This removes any question wh en discussing a case with a consultant.

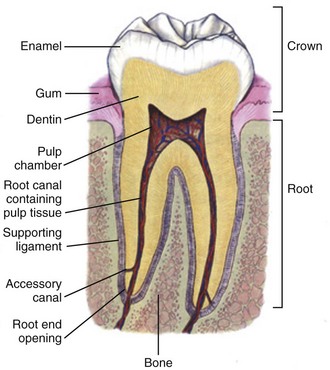

A tooth consists of the central pulp, the dentin, and the enamel (Fig. 64-3). The pulp contains the neurovascular supply of the tooth, which is responsible for carrying nutrients to the dentin, a microporous substance that consists of a system of microtubules. The dentin makes up the majority of the tooth, is a primary determinant of tooth color, and cushions the tooth during mastication. The enamel is the relatively translucent, outermost portion of the tooth and the hardest part of the body. The tooth may also be described in terms of the crown (coronal portion) and the root. The crown is the portion covered in enamel; the root is the part that serves to anchor the tooth in alveolar bone.

Figure 64-3 The dental anatomic unit.

l. Facial: The part of the tooth that faces the opening of the mouth. This is the part that you see when somebody smiles. It is a general term applicable to all teeth.

l. Labial: The facial surface of the incisors and canines.

l. Buccal: The facial surface of the premolars and molars.

l. Oral: The part of the tooth that faces the tongue or the palate. This is a general term applicable to all teeth.

l. Lingual: Toward the tongue; the oral surface of the mandibular (and maxillary) teeth.

l. Palatal: Toward the palate; the oral surface of the maxillary teeth.

l. Approximal/interproximal: The contacting surfaces between two adjacent teeth.

l. Mesial: The interproximal surface facing anteriorly or closest to the midline.

l. Distal: The interproximal surface facing posteriorly or away from the midline.

l. Occlusal: Biting or chewing surface of the premolars and molars.

l. Incisal: Biting or chewing surface of the incisors and canines.

l. Apical: Toward the tip of the root of the tooth.

l. Coronal: Toward the crown or the biting surface of the tooth.

Acute Toothache in the ED

Patients with an acute toothache (odontalgia) often come to the ED for dental evaluation and relief of symptoms. Although multiple problems can initially cause pain in the area of the teeth, the cause is usually pulpitis or dental trauma. Referral to a dentist is the logical definitive course of action, but pain relief can be initiated in the ED. Dental pain is, however, also a common complaint in drug seekers. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, narcotics, and local nerve blocks can provide relief of pain, depending on the scenario. Hile and Linklater1 recently reported significant pain relief in a fractured tooth by applying 2-octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive (Dermabond, Ethicon Products) directly to the tooth. This intervention is currently anecdotal but may also provide temporary pain relief for patients with open decay when air and temperature exacerbate the pain. Dry the tooth thoroughly with gauze, and generously apply a few layers of the product to the affected area. This intervention lasts for a few days only but should not interfere with subsequent dental intervention. Note that the use of skin adhesives has not been approved for intraoral use; they tend to break down quickly in the oral cavity.

Acute dental pain may also be referred pain, so a complete evaluation should be conducted if the area appears to be normal (Fig. 64-4). For example, acute sinusitis can cause tooth pain and vice versa. Obvious dental infection should be treated with antibiotics (e.g., penicillin, clindamycin, erythromycin, metronidazole, amoxicillin-clavulanate [Augmentin]) while awaiting dental evaluation. Chronic acetaminophen overdose is a known complication of overaggressive use of analgesics by patients unable to obtain dental care for an acute toothache.2 Unfortunately, many patients have irreversible pulpitis by the time that they seek emergency care.3

Antibiotics provide no benefit for pain from a simple toothache, dental cavity, or pulpitis, although some clinicians prescribe them because follow-up dental care may be delayed or difficult to obtain.4

Individual teeth (except the posterior molars) can be temporarily anesthetized with total pain relief by simply giving a periapical injection of a local anesthetic (see Chapter 30). Bupivacaine has a long duration of action (4 to 12 hours) and has been shown to decrease the narcotic requirement of postoperative oral surgery patients even after the anesthetic properties of the medication have worn off. Molars, which are more difficult to anesthetize with periapical injections, can be blocked via nerve block techniques. Recently, articaine (Septocaine) has been used for this purpose. It is fast acting and penetrates well. Many dentists have replaced lidocaine with articaine for local tooth anesthesia. Note, however, that this anesthetic is not used for nerve blocks, only local injection, because persistent paresthesias have been associated with nerve blocks.

Dentoalveolar Trauma

Dentoalveolar trauma is a common reason for ED visits. Injury to the maxillary central incisors accounts for between 70% and 80% of all fractured teeth.5–7 Trauma to the teeth is not usually life-threatening; however, the morbidity associated with dental fractures can be significant and includes failure to complete eruption, change in color of the tooth, abscess, loss of space in the dental arch, ankylosis, abnormal exfoliation, and root resorption. Dental injuries are often associated with intraoral lacerations. When a tooth is chipped or missing and there is a concomitant intraoral laceration, it should be noted that the missing portion of the tooth might be embedded in the depths of the laceration (Fig. 64-5).

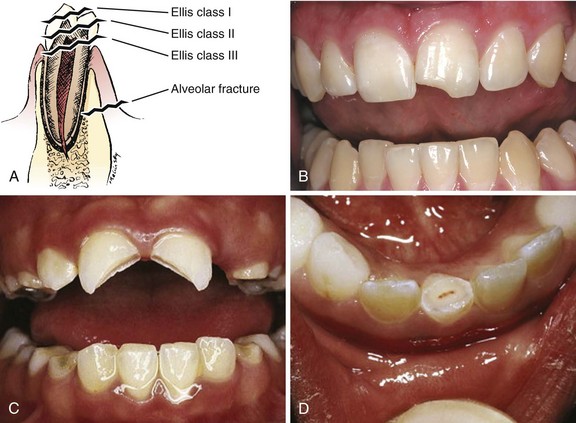

Management of fractured teeth depends on the extent of fracture with regard to the pulp, the degree of development of the apex of the tooth, and the age of the patient. Dentoalveolar injuries and, in particular, tooth fractures can be classified in many ways.8 The Ellis classification is one system often cited in the emergency medicine literature; however, many dentists and maxillofacial surgeons do not use this nomenclature, thus making it less than ideal when discussing these types of injuries (Fig. 64-6).6 The most easily understood method of classification is one based on a description of the injury.

Ellis Class I Fractures

Uncomplicated crown fractures through only the enamel are known as Ellis class I fractures (see Fig. 64-6B). They are not usually sensitive to either temperature or forced air. These fractures generally pose minimal threat to the health of the dental pulp. They may feel sharp to the patient’s tongue, lips, or buccal mucosa. Immediate treatment is not necessary but may consist of smoothing the sharp edge of the tooth with an emery board or rotary disk sander. The patient should be reassured that a dentist can restore the tooth to its normal appearance with composite resins and bonding material. Follow-up is important with these injuries because pulp necrosis and color change can occur in rare cases (<1%).6,9,10

Ellis Class II Fractures

Uncomplicated fractures through the enamel and dentin are called Ellis class II fractures. Fractures that extend into the dentin are at higher risk for pulp necrosis and therefore need more aggressive treatment by the emergency clinician (see Fig. 64-6C). The risk for pulp necrosis in these patients is less than 10%, but it increases as treatment time extends beyond 24 hours.6 These patients often complain of sensitivity to heat, cold, or forced air. Physical examination reveals the yellow tint of the dentin in contrast to the white hue of the enamel. With fractures closer to the pulp cavity, the dentin will have a pink tinge. The tooth is usually sensitive to percussion with a tongue blade. The porous nature of dentin allows passage of bacteria from the oral cavity to the pulp, which may result in inflammation and infection of the pulp chamber. This is more likely to occur after 24 hours of dentin exposure but occurs sooner if the fracture site is closer to the pulp. Likewise, patients younger than 12 years have a pulp-to-dentin ratio larger than that in mature adults and are at increased risk for pulp contamination. For this reason, younger patients should be treated aggressively and be seen by a dentist within 24 hours.10,11

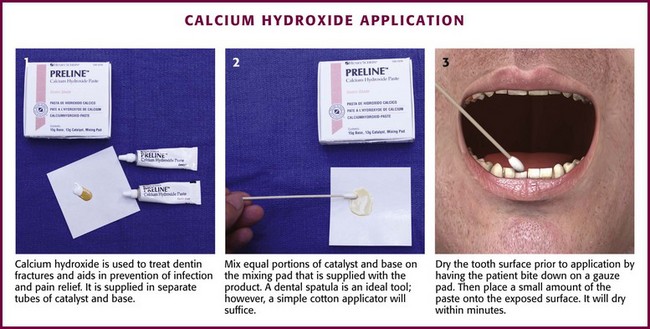

The goal of treating dentin fractures is twofold: to cover the exposed dentin and thus prevent secondary contamination or infection and to provide relief of the pain. After the tooth is covered, the dentist, using modern composites, can often rebuild the tooth directly over the calcium hydroxide (CaOH) cap that was placed in the ED. Perform supraperiosteal infiltration or a regional tooth block before any manipulation of the tooth. This will make application of the dressing easier because manipulation of the tooth will not cause discomfort. Dressings that may be applied to the surface of the tooth include CaOH, zinc oxide, skin adhesives, and glass ionomer composites. Some literature suggests that glass ionomer may be superior to other coverings; however, the difference is probably slight, and the increased cost of glass ionomer is not justified for routine use in the ED at this time.5,12 Certain composites may be cured with a bonding light. This is routinely done in the dentist’s office and is beyond the scope of most emergency practice. Bone wax and skin glue such as the cyanoacrylates are not recommended as dressings. Most dressings come as a base and a catalyst, which require mixing. This is easily accomplished with a dental spatula and a mixing pad, which can be obtained from any dental supply house. A commonly used ED dressing is calcium hydroxide (Dycal or other similar products). Mix the catalyst and the base in equal portions, and place a small amount on the exposed area with an applicator such as a dental spatula or another appropriate instrument (Fig. 64-7).

Dry the surface of the tooth before application to ensure adherence of the CaOH. Have the patient bite into gauze pads to accomplish this. Dycal will dry within minutes after being exposed to the moist environment of the mouth. Although placing dental foil over the CaOH dressing is recommended, it is not usually necessary if the patient plans to follow up with a dentist within 24 to 36 hours. To prevent dislodgment of the dressing, instruct the patient to eat only soft foods until seen by a dentist. Begin antibiotic treatment with penicillin or clindamycin until definitive dental treatment can be obtained.13

Ellis Class III Fractures

Complicated fractures involving the pulp are also known as Ellis class III fractures (see Fig. 64-6D). Complicated fractures of the crown that extend into the pulp of the tooth are true dental emergencies. These fractures result in pulp necrosis in 10% to 30% of cases even with appropriate treatment.6 They may be distinguished from fractures of the dentin by the pink color of the pulp. Wipe the fractured surface of the tooth with gauze and observe for frank bleeding or a pink blush, which indicates exposure of the pulp. Fractures through the pulp are often excruciatingly painful, but occasionally, there is lack of sensitivity secondary to disruption of the neurovascular supply of the tooth.

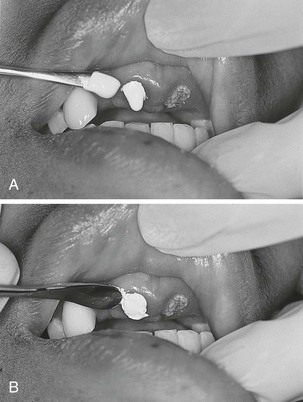

Immediate management includes referral to a dentist, oral surgeon, or endodontist. The patient often requires pulpectomy (complete removal of the pulp) or, in the case of primary teeth, pulpotomy (partial removal of the pulp) as definitive treatment.5,9 The longer the pulp is exposed, the greater the likelihood of contamination and abscess formation. If a dentist cannot see the patient immediately, attempt to relieve the pain and cover the exposed pulp (Fig. 64-8). If significant pain is present, perform a dental block. Subsequently, cover the tooth with one of the dressings described earlier. Sometimes the bleeding is brisk. Control such bleeding by applying a dressing. Ask the patient to bite onto a gauze pad that has been soaked with a topical anesthetic containing a vasoconstrictor such as epinephrine. Alternatively, inject a small amount of anesthetic/vasoconstrictor into the pulp to control bleeding. After the covering is applied, instruct the patient to follow up as soon as possible with a dentist. Antibiotics with coverage directed at oral flora (e.g., penicillin, clindamycin) should be considered and only soft foods should be eaten. Removal of the pulp with specialized instruments by the emergency clinician is not recommended, although some authors have advocated this in the past. This procedure is the realm of the dental professional and is likely to result in complications if not done properly.

Luxation, Subluxation, Intrusion, and Avulsion

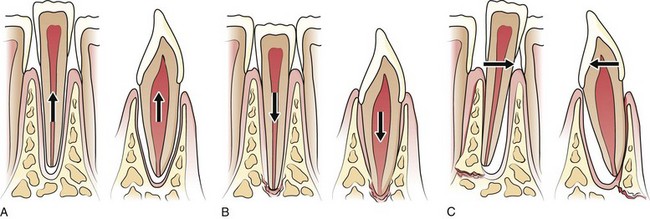

Subluxation refers to teeth that are mobile but not displaced. Luxation refers to teeth that are displaced, either partially or completely, from their sockets. Luxation injuries are divided into four types (Fig. 64-9):

1. Extrusive luxation is an injury in which the tooth is forced partially out of the socket in an axial direction (see Fig. 64-9A).

2. Intrusive luxation, or intrusion, occurs when the tooth is forced apically. It may be accompanied by crushing or fracture of the tooth apex (see Fig. 64-9B).

3. Lateral luxation occurs when the tooth is displaced either facially, lingually, mesially, or distally (see Fig. 64-9C). This injury is often associated with injuries to the alveolar wall.

4. Complete luxation, also known as complete avulsion, results in loss of the entire tooth from the socket.

Teeth that are minimally mobile and are not displaced do very well with just conservative treatment. The tooth will tighten up in the socket if not retraumatized. Instruct patients to eat only a soft diet for 1 to 2 weeks and see their dentist as soon as possible. Note that a seemingly lost (avulsed) tooth may actually be deeply intruded into the soft tissue (Fig. 64-10).

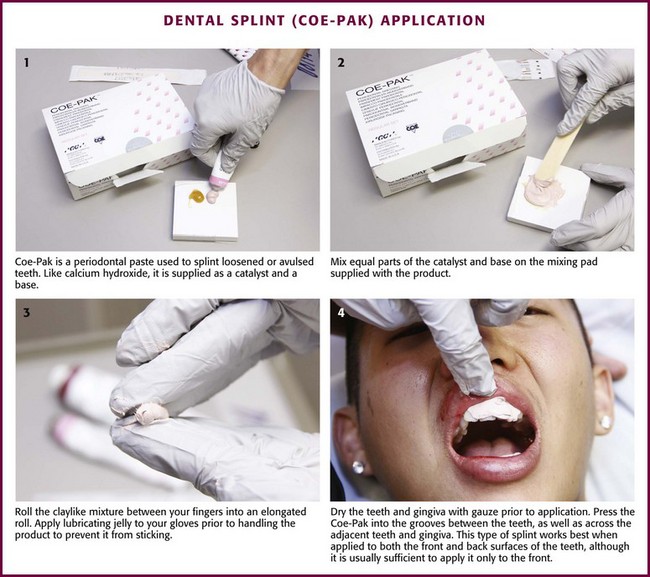

Grossly mobile teeth require some form of stabilization as soon as possible. It is important to note that in certain patients with poor gingival health, luxated teeth may not be salvageable because of disease of the attachment apparatus. Stabilization is best performed by a dental specialist with enamel bonding material or wire ligation. Although many different “home remedies” exist for splinting loosened teeth in the ED, the clinician must be aware of the possibility of aspiration of teeth if the splint fails. Avoid the use of unapproved medications in the mouth. Splinting techniques are suitable for the emergency clinician to perform as temporizing measures until definitive care can be arranged. One simple technique for emergency use is to apply periodontal paste, commercially available as Coe-Pak or other similar commercial products (Fig. 64-11). These products usually consist of a base and a catalyst that when mixed, form a moderately sticky claylike dressing that becomes firm after application. It is applied over the enamel and gingiva, as well as the adjacent teeth, to splint the subluxed tooth into place. Although the splint performs best if placed on the facial and buccal surfaces of the teeth, it is usually sufficient to apply the paste only to the front (facial) surface of the teeth. Make sure that the gingiva and enamel are completely dry. Lubricate your gloves with water or lubricating jelly before applying the dressing. Apply the dressing into the grooves between the teeth, as well as on the adjacent teeth. Remind the patient to eat a soft diet until seen in follow-up within 24 hours. Coe-Pak and other similar products are usually fairly simple for the dentist to remove during formal restoration.

Figure 64-11 Dental splint (Coe-Pak) application.

Intrusion and Avulsion

Intruded teeth are those that have been forced apically into the alveolar bone. This often results in disruption of the attachment apparatus or fracture of the supporting alveolar bone, especially in permanent teeth with mature roots.11,14 These teeth are usually immobile and do not require stabilization in the ED. Intruded teeth frequently require endodontic treatment because of pulp necrosis. It is important to consider the possibility of an intruded tooth anytime there is a space in the dentition (see Fig. 64-10). Undiagnosed intrusion of the teeth can lead to infection and craniofacial abnormalities. Obtain radiographs when it is uncertain whether a tooth is intruded or simply avulsed. Intruded teeth are best managed by a dentist or dental specialist; referral should take place within 24 hours. Permanent teeth often require repositioning and immobilization, but primary teeth are usually given a trial period to erupt on their own before any intervention is taken.

Primary teeth are not replaced after avulsion because they can fuse to the alveolar bone and potentially cause craniofacial abnormalities or infection. Reimplanted primary teeth may also interfere with eruption of the secondary teeth. The parents of these patients need to be reassured that a prosthetic replacement for the avulsed teeth can easily be made and worn until the permanent teeth erupt. See Figures 64-1 and 64-2 as a guide to identifying permanent versus primary teeth.

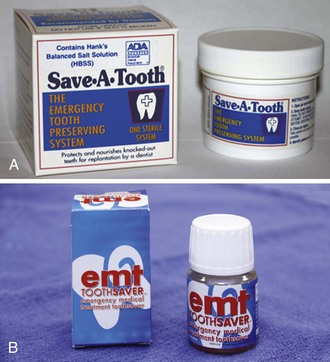

The first consideration in treating dental avulsions is to ask, “Where is the tooth?” Missing teeth may have been intruded, fractured, aspirated, swallowed, or embedded into the soft tissues of the oral mucosa. Therefore, radiographs should be considered anytime that an avulsed tooth cannot be located. Management of an avulsed tooth in the ED depends on a number of factors, including the age of the patient, the amount of time that has elapsed since the tooth was avulsed, associated trauma to the oral cavity such as alveolar ridge fractures, and the overall health of the periodontium.14 Time is the other important consideration when deciding whether to replace an avulsed tooth. In general, the longer the tooth is out of the socket, the higher the incidence of necrosis of the periodontal ligament and subsequent failure of reimplantation. Periodontal ligament cells generally die within 60 minutes outside the oral cavity if they are not placed in an appropriate transport medium.15 A significant amount of research has been conducted on different media used to keep cells of the periodontal ligament alive. Various transport media have been studied, including milk, Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution, Save-A-Tooth, saliva, cell culture media, and water. Although certain cell culture media have been developed to stimulate cells of the periodontal ligament to proliferate and remain viable, milk and the commercially available Save-A-Tooth and EMT Toothsaver are the best and easiest for both prehospital care and ED storage (Fig. 64-12).15,16 Milk will preserve the periodontal ligament for 4 to 8 hours; the commercial products will preserve the ligament for 12 to 24 hours. However, reimplantation should take place at the earliest possible opportunity after the socket has been adequately prepared. The key is to get the tooth into the transport medium immediately because even 10 minutes outside some type of storage medium can cause desiccation and death of the periodontal ligament cells. Use saliva at the scene if milk, EMT Toothsaver, or Save-A-Tooth is not available. The patient should reimplant the tooth in the prehospital setting if possible. The principles cited here should be followed when providing instructions to prehospital providers or to a patient who calls for advice. It is always preferable to refer such patients directly to a dentist rather than the ED if this is practical. Patients should be requested do the following:

l. Determine whether this is a permanent tooth. By 14 years of age, all primary teeth should have been lost.

l. Handle the tooth by the crown only because handling the tooth by the root can damage the alveolar ligament.

l. Do not replace the tooth if it is fractured or if significant maxillofacial trauma has occurred such as an alveolar ridge fracture.

l. If the tooth can be replaced in the prehospital setting, gently rinse off the root first to remove any debris. Do not wipe off the root because this removes the periodontal ligament.

l. If the tooth cannot be reimplanted successfully in the field, place it in a transport medium as described earlier. Do not transport the tooth in the oral cavity such as inside the the cheek because it can be aspirated. This location is also not ideal for keeping the periodontal ligament alive because of the bacterial flora and low osmolality of saliva.

l. Store the tooth in an appropriate medium if reimplantation is delayed for any reason.

l. Perform supraperiosteal dental infiltration with a local anesthetic before manipulating or replacing teeth to make the procedure more comfortable for the patient and easier to perform.

l. Check the oral cavity for trauma. If an alveolar ridge fracture is present or the socket is significantly damaged, do not reimplant the tooth.

l. Gently suction the socket first with a Frasier suction tip to remove any accumulated clot. Be careful to not damage the walls of the socket because this can further damage periodontal ligament fibers. Irrigate gently after suctioning. If the clot is not removed, reimplantation and realignment will be difficult. Rinse off any debris on the tooth with saline but do not scrub it. Implant the tooth into the socket with firm, but gentle pressure. Remember to handle the tooth only by the crown.

l. Ask the patient to bite down gently on gauze to help align the tooth. The tooth may require splinting after replacement. If significant mobility is present such that temporizing splints are not adequate, consult a dentist to see whether wiring or arch bars are necessary.

l. Update the patient’s tetanus status as necessary.

l. Prescribe a liquid diet until the patient is seen in follow-up.

Antibiotics are controversial in the treatment of fractured and avulsed teeth. Although the American Association of Endodontics does not recommend the routine use of antibiotics for fractures or avulsions, other authors recommend the use of antibiotics effective against mouth flora (e.g., penicillin, clindamycin) to decrease inflammatory resorption of the root.6,17 It is probably reasonable to use antibiotics if the root or socket is heavily soiled; otherwise, treatment should be tailored to the individual patient and discussed with a knowledgeable and experienced consultant.

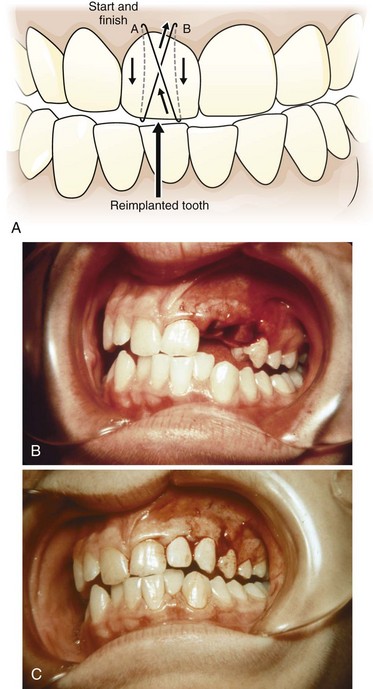

Ideally, but rarely possible in real life, the patient is immediately referred to a dentist, and the reimplanted tooth is held in place by biting on gauze. The tooth may be temporarily held in place with Coe-Pak or another similar product (see Fig. 64-11) or the technique described in Figure 64-13.

Alveolar Bone Fractures

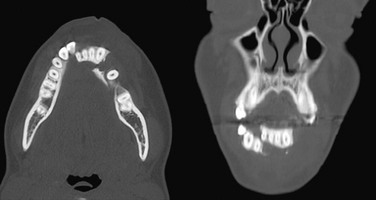

Trauma involving the anterior teeth may be associated with fracture of the alveolus, which is the tooth-bearing portion of the maxilla or mandible. Alveolus or alveolar ridge fractures often occur in multitooth segments and will vary in the number of teeth involved, the amount of displacement, and the mobility of the affected segment. The patient generally complains of pain, as well as malocclusion. The diagnosis is usually clinically apparent and is notable for a section of teeth that are misaligned and variable in mobility (Fig. 64-14). Avulsed teeth, fractured teeth, or displaced teeth may be present within the alveolar segment itself. Dental bite-wing radiographs confirm the diagnosis. In the ED, Panorex or facial x-ray films may show the fracture line just apical to the root of the involved teeth; however, these films are often inconclusive or have normal findings. Facial computed tomography (CT) may provide additional information (Fig. 64-15).

Treatment of alveolar ridge fractures involves rigid splinting after repositioning the involved segment. This is usually beyond the scope of the emergency clinician, and urgent consultation with an oral surgeon or dentist is necessary. The role of the emergency clinician is to identify the injury, as well as any avulsed or fractured teeth, and preserve as much of the alveolar bone and surrounding mucosa as possible. Alveolar bone that is lost, débrided, or missing is difficult to restore properly.12

Lacerations and Dentoalveolar Soft Tissue Trauma

As a general rule, repair injured teeth before undertaking soft tissue repair because manipulating the soft tissue while repairing teeth may damage sutures already in place in the soft tissues. Begin repair in the perioral region with standard wound care. After appropriate local or regional anesthesia, débride devitalized, crushed, or macerated tissue. Irrigate profusely. The role of antibiotics in mucosal trauma has not been conclusively established, and there is no definitive standard of care. Several studies suggest a minimal benefit; however, this remains to be completely proved.18 A reasonable guideline to follow is to use antibiotics if a significant amount of devitalized or crushed tissue is present or if the wound is a through-and-through laceration. Coverage of oral flora (e.g., penicillin, clindamycin) is fine for mouth lacerations, and additional skin coverage (e.g., clindamycin, dicloxacillin) should be considered for through-and-through lacerations. Dentoalveolar trauma may present the emergency clinician with several different situations that should generally be approached as follows.

Gingiva

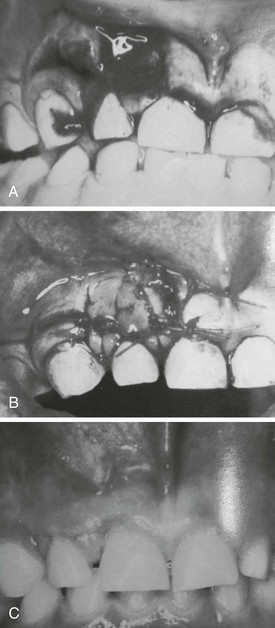

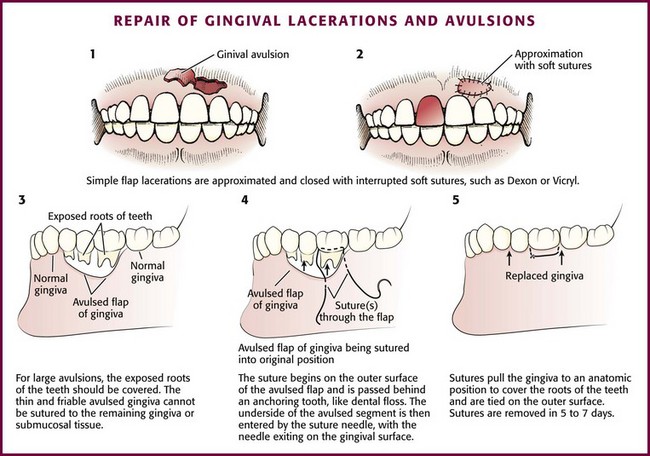

Small lacerations of the hard gingiva overlying the maxillary or mandibular alveolus usually heal uneventfully without repair. If the laceration is large, if a flap is present, or if bone is exposed, approximate the gingiva with a 4-0 or 5-0 Vicryl or Dexon suture. As mentioned earlier, silk is another option. It is difficult to suture gingiva because there is little supporting soft tissue underneath. A helpful technique is to wrap the suture around the teeth circumferentially and use the teeth as anchors (Fig. 64-16). Large lacerations should be repaired to approximate the gingiva and cover the base of the teeth (Figs. 64-17 and 64-18).

Figure 64-17 Large gingival avulsions should be approximated to an anatomic position with interrupted sutures.

Figure 64-18 Repair of gingival lacerations and avulsions.

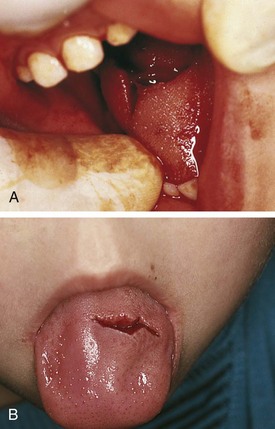

The Tongue

Tongue lacerations are challenging. Although they may be tempting to suture, most large lacerations of the body of the tongue, such as those that occur from a seizure, will heal well without suturing (Fig. 64-19). Tongue lacerations that have the wound edges approximated do not need to be sutured. Repair larger lacerations that gape because the cleft left by the wound will epithelialize and leave a grooved or bifid or lateral flap appearance. Approximate wounds that are bleeding profusely, are flap shaped, involve muscle, or are on the edge of the tongue. Small avulsions (divots) or those in the center of the tongue usually heal without intervention.

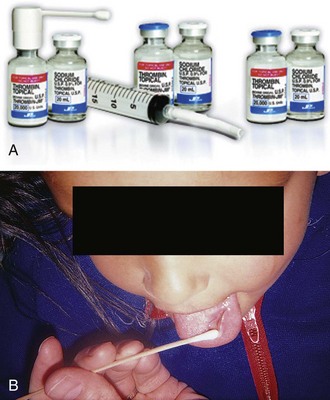

Begin the repair with either local infiltration of an anesthetic or a lingual block (see Chapter 30). To promote hemostasis, infiltrate locally with lidocaine with epinephrine. Use absorbable sutures such as 4-0 chromic, Vicryl, or Dexon. Silk can be used, but it must be removed in 7 to 10 days. Do not use nylon because it is very irritating to the surrounding tissues. For lacerations extending through muscle, close with one deep stitch penetrating both the mucosa and the muscle. When possible, bury the knots of absorbable suture because they will often work their way loose. Full-thickness lacerations can be closed in a number of ways. Place a suture through all three layers or close the top mucosa and muscle together and do the same thing on the underside of the tongue. Bleeding from large lacerations is almost always controlled with primary repair. In some instances, hemostasis can be achieved without the use of sutures by using Gelfoam impregnated with topical thrombin (Fig. 64-20).

Oral Hemorrhage

Direct Pressure

If the bleeding persists, insert a coagulation sponge, such as Gelfoam, into the socket and then loosely close the gingiva surrounding the socket with a 3-0 absorbable figure-of-eight suture. Instruct the patient to bite down on gauze placed over the sutures. Soaking Gelfoam with topical thrombin before placement is a good way to halt minor persistent bleeding (see Fig. 64-20). A new agent showing great promise for oral hemorrhage is the chitosan dental bandage (HemCon), which is designed specifically for postextraction and oral bleeding. This shrimp-based bandage forms a sticky matrix when it contacts blood, and it quickly forms a seal that stops the bleeding. If these measures fail to control the bleeding, consult a specialist. It is also reasonable to check blood counts and coagulation profiles at this time.

Alveolar Osteitis (Dry Socket)

1. Moderate to severe pain localized to the area or frequently radiating to the ear

2. A foul odor or taste in the absence of purulence or suppuration

3. Symptoms that occur 3 to 5 days after tooth extraction

Anything that increases negative intraoral pressure in the mouth (e.g., smoking, excessive rinsing, spitting, drinking from a straw), as well as hormone replacement and periodontal disease, will predispose a patient to a dry socket. In only a small percentage of patients (2% to 5%) will a dry socket develop; however, this number increases with traumatic extractions or impacted third molars.13,19

The following contribute to the development of a dry socket:

1. Excessive trauma during extraction

2. Inadequate blood supply to the extraction site

3. Preexisting localized infection

4. Loss of clot from sucking, straw use, rinsing, or smoking

Gauze (¼ inch) impregnated with eugenol (oil of cloves) or a local anesthetic may be used. Replace the gauze in 24 to 36 hours because it tends to dry out and loosen. The patient should be seen by a dentist the next day if at all possible. The socket may also be packed with a slurry of Gelfoam and eugenol. The Gelfoam acts as a matrix to hold the eugenol in the socket. A commercial product, such as Dry Socket Paste or Dressol-X (Fig. 64-21), can also be applied by itself into the socket or mixed with Gelfoam and placed into the socket. Dry Socket Paste is a very sticky thick paste containing eugenol. It may stay in place longer than gauze and does not dry out. Whichever packing material is used for a dry socket, one or more packings might be necessary before healing is complete.

Figure 64-21 Dry Socket Paste.

Although antibiotics may be given to prevent alveolar osteitis, they are not usually necessary once the socket has been packed and should be prescribed at the discretion of the patient’s oral surgeon or dentist.11–13 NSAIDs should also be prescribed because they seem to work better than narcotics for dry socket.20

Dentoalveolar Infections

Disease of the Periodontium

Periodontal disease is also very common and affects practically all adults to some degree. Periodontal disease refers to infection of the attachment apparatus of the teeth: the gingiva, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone. Unlike pulpal disease, periodontal disease is not usually symptomatic and is therefore rarely a primary reason to seek treatment in the ED. Gingivitis is an inflammation of the gingiva caused by bacterial plaque. In advanced disease, the gingiva becomes red and inflamed and tends to bleed easily. With chronic periodontal disease, an abscess can form when organisms become trapped in the periodontal pocket. The purulent material usually escapes through the gingival sulcus; however, it occasionally invades the supporting tissues, the alveolar bone, and the periodontal ligament (periodontitis). Periodontal abscesses that are not draining spontaneously through the sulcus can be drained in the ED. Saline rinses are encouraged to promote drainage. Antibiotics should be reserved for severe cases or for abscesses that cannot be drained. If it is uncertain whether the abscess originates from the pulp or the periodontium, prescribe antibiotics even if the abscess has been drained.13,19

Drainage of Dentoalveolar Infections

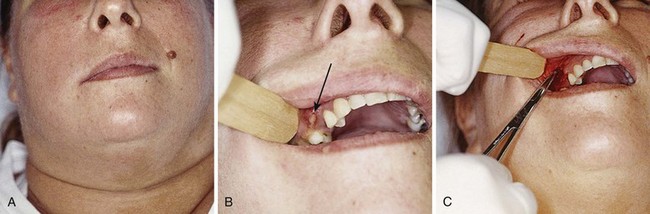

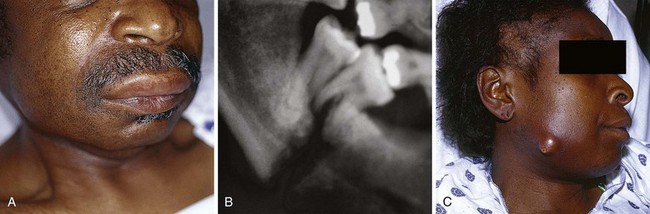

The important determination for the emergency clinician to make is whether the odontogenic infection is localized, confined, and easily accessible or whether it is complex and involves several potential spaces. Likewise, determine whether the patient appears to be in a toxic state, has trismus, or exhibits any signs of airway compromise. Patients not meeting these criteria require specialist referral. Dental infections are not always obvious and can be mistaken for sinusitis, or vice versa (Figs. 64-22 and 64-23).

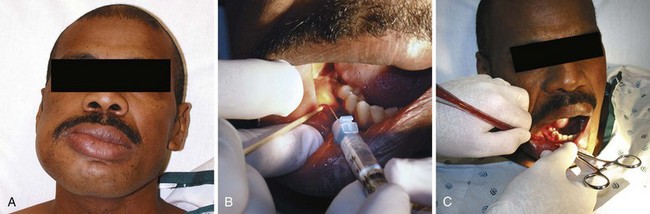

Several anesthetic techniques can make the drainage process more comfortable. Nerve blocks and local injections work best. Benzocaine 20% gel or a combination of lidocaine, prilocaine, and tetracaine generally provides good topical anesthesia before injection (Fig. 64-24). Application of these medications to the dry mucosa before injection of the local anesthetic decreases the pain associated with injection. After applying the topical anesthetic, slowly infiltrate local anesthetic with a vasoconstrictor until the tissue blanches. Either a short-acting anesthetic (2% lidocaine) or a longer-acting anesthetic (0.5% bupivacaine) may be used, depending on the clinical circumstances. Regional or dental blocks may be performed instead of local infiltration if needle placement would track already infected tissues into healthy areas. Otherwise, consider local infiltration over the site of the abscess. Instruments necessary for drainage of dentoalveolar abscesses are those usually found on a standard incision and drainage tray and include hemostats, scalpel (No. 15 or 11 blade), packing material (¼-inch gauze), and a fenestrated Penrose drain.

Extraoral Technique

Most simple dental infections can be drained intraorally, but occasionally, an abscess spreads to the face and requires drainage through the skin. It is important to realize that most dental infections should be drained through the mouth, if possible, because any extraoral drainage will cause some scarring. Abscesses on the face, which should be drained in the ED, are usually very localized and fluctuant and have not spread to any of the deep spaces in the head or neck. It is also important to never make any incisions on the face in direct proximity to important structures such as the facial nerve or the parotid gland and duct. Refer to Chapter 37 for more detail on the incision and drainage technique.

Deep Space Infections of the Head and Neck

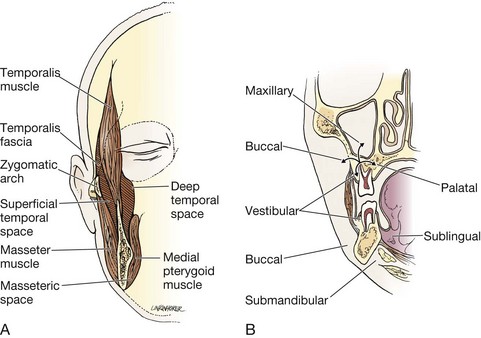

It is not unusual for odontogenic infections to spread into the various potential spaces of the face and neck (Fig. 64-25). The signs and symptoms consist of fever, chills, pain, difficulty with speech or swallowing, and trismus. Although infections of certain teeth usually spread to particular contiguous spaces, the rapid spread of these infections often makes localizing the exact space difficult. Any space, including the buccal, temporal, submasseteric, sublingual, submandibular, parapharyngeal, and others, may be involved (Figs. 64-26).

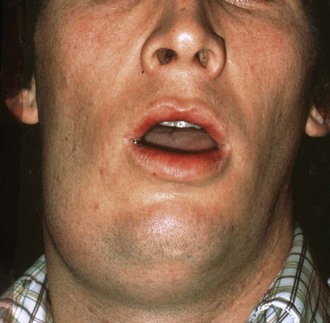

The submandibular space connects with the sublingual space. Infection involving both these spaces is known as Ludwig’s angina, which can be life-threatening. The source is usually a decayed lower tooth, with the tooth itself being relatively asymptomatic (Fig. 64-27). Initially, this infection may be subtle, but it can progress rapidly. As the infection progresses, the submandibular, submental, and sublingual spaces all become edematous, and there may be elevation of the tongue and the soft tissues of the mouth (Fig. 64-28). This is not a simple abscess that can be readily drained. It is considered a true dental emergency. Intervention includes intravenous antibiotics and emergency ear, nose, and throat (ENT) or oral surgery consultation. Patients with established cases of Ludwig’s angina cases are admitted to the hospital and undergo operative intervention often involving multiple drains. Minor early cases can be treated and observed for 6 to 8 hours in the ED with close follow-up if the infection is deemed benign. The soft tissues of the posterior aspect of the pharynx can also become involved. Securing the airway becomes of paramount importance. The suprahyoid region of the neck appears tense and indurated, and landmarks may be obscured. A CT scan can further delineate Ludwig’s angina if the diagnosis is in doubt, but in most cases, if the diagnosis is suspected, emergency consultation should be instituted early with careful monitoring for airway compromise.

Treatment of complicated odontogenic head and neck infections centers on airway management, surgical drainage, and antibiotics. If it is uncertain whether the deep spaces are involved, obtain a CT scan to delineate any extension of the infectious process. Perform airway interventions early if there is any question of compromise, and consider tracheostomy. Consult an oral maxillofacial or ENT surgeon because drainage and removal of necrotic tissue might be necessary. Administer antibiotics to slow spread of the infection down and decrease hematogenous dissemination. The bacteria involved are typically a combination of streptococci and staphylococci, but a mixed aerobic and anaerobic infection is also possible. There has been an emergence of β-lactamase–producing organisms in upward of 40% of isolates from odontogenic neck abscesses.19 Antimicrobials of choice for complicated odontogenic infections usually include the penicillins. The expanded-spectrum penicillins (ampicillin-sulbactam, ticarcillin–clavulanic acid, piperacillin-tazobactam) are effective against β-lactamase–producing bacteria and also cover the anaerobe Bacteroides fragilis. Clindamycin is an effective choice in patients who are allergic to penicillin. It should be used in combination with a cephalosporin, such as cefotetan or cefoxitin, to cover recently emerging resistant organisms. It is important to realize that in many of these infections, antibiotics are an adjunctive therapy and not a substitute for surgical intervention.

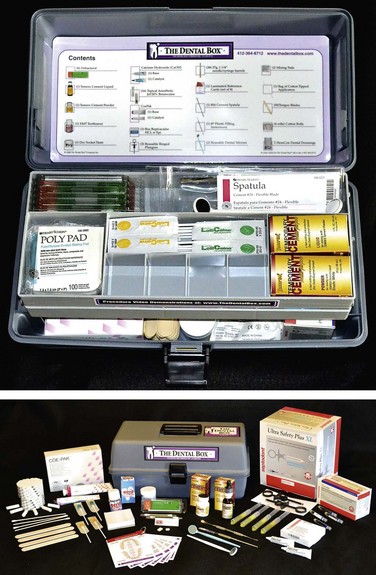

Dental Material

3. Calcium hydroxide paste, glass ionomer cement, or zinc oxide cement

4. Dry Socket Paste or eugenol

5. Topical anesthetic gel (20% benzocaine or 5% lidocaine)

6. Topical bactericidal intraoral solution (Ora-5)

7. Periodontal paste (Coe-Pak) or self-cure composite

8. Articaine (Septocaine) cartridges with epinephrine

9. Save-A-Tooth Tooth Preservation System, EMT Toothsaver, or fresh milk

10. Zinc oxide/eugenol temporary cement (Temrex)

12. Stainless steel spatula and mixing pads

13. Oral surgery tray with arch bars and ligature wires

Regional dental supply houses are good sources for these items. The Dental Box is a commercially available kit that contains many of these items and is designed for ED use (Fig. 64-29). It is available at thedentalbox.com.

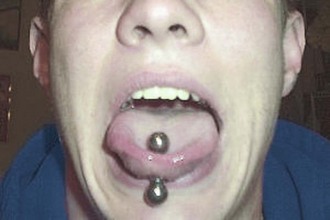

Intraoral Piercing

Dating back to antiquity, body piercing has been practiced in many countries and cultures as part of ceremonial and religious rites. In recent years, body and intraoral piercing has gained tremendous popularity throughout the world as a means of self-expression. In the ED, clinicians may see patients with piercings of the lips, tongue, and even uvula. Complications of oral piercing on the gums and teeth include pain, infection, bleeding, increased salivary flow, difficulty swallowing, gingival recession, gingival trauma, and chipped or fractured teeth. Repeated trauma from a metal tongue ball can be quite detrimental to teeth and cause microfractures and a sudden shattered tooth (Fig. 64-30). One study of 400 consecutive patients at a military dental office found that 20% of their patients had at least one type of oral piercing, with the tongue being the most common location.21 Of these patients, 14% had fractured teeth and 27% had recession of the gums. Another study assessed the impact of time and found that tooth chipping was found on molars and premolars in 47% of patients who had a tongue piercing for longer than 4 years.22

References

1. Hile, L, Linklater, DR. Use of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate for the repair of a fractured tooth. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:424.

2. Thomas, MB, Moran, N, Smart, K, et al. Paracetamol overdose as a result of dental pain requiring medical treatment—two case reports. Br Dent J. 2007;203:25.

3. Nusstein, JM, Beck, M. Comparison of preoperative pain and medication use in emergency patients presenting with irreversible pulpitis or teeth with necrotic pulps. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;96:207.

4. Keenan, JV, Farman, AG, Fedorowicz, Z, et al. Antibiotic use for irreversible pulpitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2005. [CD004969].

5. Blatz, MB. Comprehensive treatment of traumatic fracture and luxation injuries in the anterior permanent dentition. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2001;13:273.

6. Dale, R. Dentoalveolar trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2000;18:521.

7. Rauschenberger, CR, Hovland, EJ. Clinical management of crown fractures. Dent Clin North Am. 1995;39:25.

8. Ellis, SG. Incomplete tooth fracture—proposal for a new definition. Br Dent J. 2001;190:424.

9. Bakland, LK, Milledge, T, Nation, W. Treatment of crown fractures. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1996;24:45.

10. Flores, MT, Andreasen, JO, Bakland, LK, et al. The International Association of Dental Traumatology: guidelines for the evaluation and management of traumatic dental injuries. Dent Traumatol. 2001;17:1.

11. Amsterdam, J. Dental disorders. In Rosen P, Barkin R, eds.: Emergency Medicine, Concepts and Clinical Practice, 6th ed, St. Louis: Mosby, 2006.

12. Beaudreau, R. Oral and dental emergencies. In Tintinalli J, Kelen G, Stapczynki S, eds.: Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 5th ed, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000.

13. King, R. Orofacial infections. In: Montgomery MT, Redding SW, eds. Oral-Facial Emergencies: Diagnosis and Management. Portland, OR: JBK Publishing, 1994.

14. Barrett, EJ, Kenny, DJ. Avulsed permanent teeth: a review of the literature and treatment guidelines. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1997;13:153.

15. Marino, TG, West, LA, Liewehr, FR, et al. Determination of periodontal ligament cell viability in long shelf-life milk. J Endod. 2000;26:699.

16. Olson, BD, Mailhot, JM, Anderson, RW, et al. Comparison of various transport media on human periodontal ligament cell viability. J Endod. 1997;23:676.

17. Trope, M. Current concepts in the replantation of avulsed teeth. Alpha Omegan. 1997;90:56.

18. Steele, MT, Sainsbury, CR, Robinson, MA, et al. Prophylactic penicillin for intraoral wounds. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:847.

19. McQuone, S. Neck emergencies. In: Eisele D, McQuone S, eds. Emergencies of the Head and Neck. St. Louis: Mosby, 2000.

20. Dionne RA, Phero JC, Becker DE, eds. Management of Pain and Anxiety in the Dental Office. St. Louis: Saunders, 2002.

21. Levin, L, Zadik, Y, Becker, T. Oral and dental complications of intra-oral piercing. Dent Traumatol. 2005;21:341.

22. Campbell, A, Moore, A, Williams, E, et al. Tongue piercing: impact of time and barbell stem length on lingual gingival recession and tooth chipping. J Periodontol. 2002;73:289.