122 Emergency Delivery and Peripartum Emergencies

• If shoulder dystocia is encountered, attempt the McRoberts maneuver with suprapubic pressure while simultaneously calling for obstetric assistance.

• Practitioners underestimate blood loss in postpartum hemorrhage by as much as 50%.

• Uterine inversion is relatively uncommon but is associated with significant morbidity if not recognized and treated promptly.

• Up to 87% of patients with uterine rupture have no pain, and up to 89% have no vaginal bleeding.

• Perimortem cesarean delivery is indicated in gravid patients if more than 24 weeks pregnant and if arrest continues after 4 to 5 minutes of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

• The clinical examination of a term pregnant patient is notoriously unreliable.

• Treatment of anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy is similar to that for sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation and should begin immediately; the diagnosis is one of exclusion, and patients must be treated promptly to survive.

Emergency Delivery

Pathophysiology

For a description of potential malpresentation, along with management recommendations, see www.expertconsult.com

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

In the emergency department (ED), the majority of patients seen in labor are in the latter part of stage I or stage II.1 Precipitous delivery is a common occurrence because most patients whose labor progresses more slowly will have time to get to their designated obstetric facility.

Treatment

For more information on the management of difficult labor, see www.expertconsult.com

If delivery is imminent, the patient will have to remain in the ED. A gynecologic bed with lithotomy position capability is ideal, and a resuscitation bay with greater accessibility and equipment is recommended. A radiant warmer and appropriate airway equipment should be available. Positioning of the mother may require an approximate 10-degree tilt to the left to prevent uterine pressure on the inferior vena cava and associated hypotension. When crowning occurs, the mother should be instructed to push along with the contractions, with the physician positioned in front of the introitus ready to accept the fetus. As soon as the head is accessible, continuous gentle countertraction should be administered to maintain it in a flexed position. This technique provides control of an explosive delivery, as well as avoidance of the high morbidity associated with fetal neck hyperextension. Though once recommended, the modified Ritgen maneuver has recently been shown to be associated with an increased rate of third-degree lacerations and episiotomy in comparison with a “hands-off” approach.2 Similar rates of perineal tears were found for each modality.

Postpartum Hemorrhage

Epidemiology

Hemorrhage is a significant cause of maternal morbidity and is the second most common cause of peripartum deaths (following amniotic fluid embolism). Hemorrhage was a direct cause of more than 18% of 3201 pregnancy-related maternal deaths in the United States from 1991 to 1997.3 Worldwide, hemorrhage has been identified as the single most important cause of maternal death and is responsible for almost half of all postpartum deaths in developing countries.4

Postpartum hemorrhage is the term used to describe excessive blood loss after delivery. Classically, it is defined as more than 500 mL of blood loss in a vaginal delivery or more than 1000 mL of blood loss in a cesarean delivery; however, careful quantitative measures reveal that blood loss in the range of 500 to 1000 mL is actually average for both types of delivery. Of note, practitioners often underestimate blood loss by as much as 50%.5 For the ED physician, the most important causes of hemorrhage in the postpartum period are birth trauma, uterine atony, uterine rupture, and uterine inversion.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

In a reported case series on uterine inversion, the most common signs were shock and hemorrhage.6 With a complete inversion, the prolapsed uterus may be visible as a large, dark red polypoid mass within the vagina or protruding through the introitus. If the fundus remains within the vagina, the diagnosis may be suspected because of dimpling, indentation, or absence of the uterine fundus on abdominal examination or because a mass is palpated in the cervix on bimanual examination. Establishing the diagnosis of incomplete inversion can be quite difficult; severe hypotension, postpartum hemorrhage, and subtle abnormalities on abdominal examination may be the only clues.

Uterine rupture is also a difficult clinical diagnosis and should be considered in any patient with unexplained peripartum hemorrhage or hypotension. The classic findings of uterine rupture are “ripping” or “tearing,” suprapubic pain and tenderness, absence of fetal heart sounds, recession of the presenting parts, and vaginal hemorrhage. Signs and symptoms of hypovolemic shock and hemoperitoneum may follow. This classic manifestation is actually rare; 87% of patients with uterine rupture have no pain and 89% have no vaginal bleeding. Pain is also an unreliable finding because of the altered response to noxious intraperitoneal stimuli by a stretched abdominal wall. Fetal distress is the most consistent finding (80% to 100%), with fetal bradycardia being the most common sign.7 Most reports of uterine rupture describe patients with normal blood pressure or even elevated blood pressure without tachycardia. Abnormal maternal vital signs are late indicators of severe hemorrhage. The most important risk factor for uterine rupture is a previous uterine scar; other factors are listed in Box 122.1.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Without palpation or visualization of a frankly prolapsed uterus, it may be difficult to differentiate uterine inversion from severe atony. Heavy bleeding may make visualization of the cervix impractical. In addition, accurate abdominal palpation for a uterine fundus may be impossible in an obese patient. Depending on factors such as patient stability, resources, and diagnostic uncertainty, ultrasonography or laparotomy may be necessary. In stable patients in whom the diagnosis is uncertain and resources are available, prompt ultrasound scanning may be helpful.9 Ultrasonography may be able to identify retained products or clot in the uterus, but manual exploration is still needed. Ultrasound can also help detect peritoneal free fluid suggestive of uterine rupture. In selected circumstances in stable patients, a computed tomography scan can be useful in making the diagnosis in those with postpartum hemorrhage (retroperitoneal hematoma). If the accompanying hemorrhage or shock is sufficiently alarming to require immediate exploration, the correct diagnosis may be established only at laparotomy.

Treatment

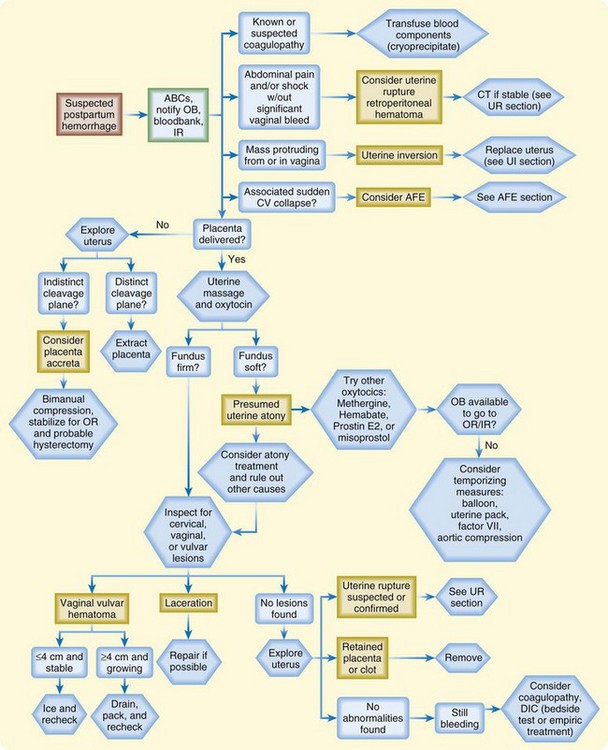

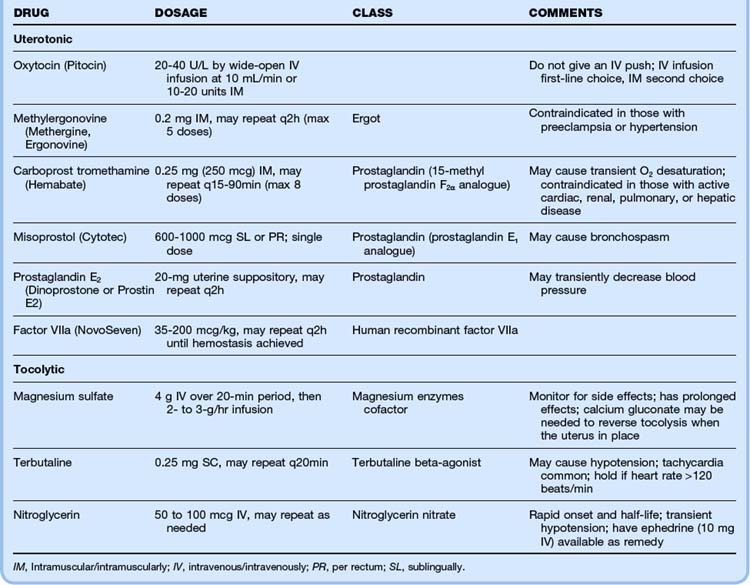

The most important aspects of managing postpartum hemorrhage are obtaining hemostasis and treating shock, including supplemental oxygen, placement of two large-bore intravenous (IV) lines, hemodynamic monitoring, and volume replacement. In addition, blood should be typed and crossmatched and 4 to 6 units of packed red blood cells should be available. Consultation with the obstetrics service should be arranged. Along with the initial resuscitation, bimanual massage and IV oxytocin should be initiated (Fig. 122.1 and Table 122.1). A Foley catheter should be placed.

First-line interventions for atony are part of the initial management of postpartum hemorrhage—namely, initiation of bimanual uterine compression, IV oxytocin, and clearing of products of conception and clots from the uterus. If bleeding persists after the initial interventions, additional uterotonic medications should be given (see Table 122.1). The choice of agent may be influenced by the side effect profile, but the best drug is probably the agent that is the most quickly available in the ED. Interventional radiology may be beneficial because embolization may control the bleeding. In any case, temporizing measures may be required until definitive intervention (Table 122.2).

Table 122.2 Temporizing Measures for Hemostasis of Postpartum Hemorrhage

| METHOD | PROCEDURE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|

| Uterine packing | Layer sterile gauze within the uterus, with the distal end going out through the os | May adhere to the uterine wall and removal required; does not allow monitoring of ongoing bleeding; start prophylactic antibiotics |

| Balloon tamponade | If available and time allows, use bedside ultrasonography to confirm that the balloon is beyond the internal os before inflation to avoid damage to the cervical canal; give prophylactic antibiotics and continue oxytocin infusion | |

| Foley catheter | Insert a large bulb catheter (24 French) into the uterus Instill with 80-100 mL of saline Pack the vagina to avoid expulsion of the catheter |

Multiple catheters may be needed (in a sterile overbag), which makes the inner lumen difficult to monitor |

| SOS Bakri balloon | Insert into the uterus Instill 300-500 mL of saline through the stopcock Pack the vagina |

Best option if available; allows direct measurement of ongoing bleeding via the open inner lumen; developed for postpartum hemorrhage; balloon conforms to the shape of the uterine cavity |

| Sengstaken-Blakemore tube | Cut off the distal (“stomach”) end of the tube Insert inside the uterine cavity Infuse 75-300 mL of saline Pack the vagina to avoid expulsion of the tube |

Does not conform to the shape of the uterine cavity; with the end cut off, proximal bleeding can be monitored through the lumen; may be available from the gastrointestinal department laboratory if not available in the emergency department |

| Rusch catheter | Using a 60-mL bladder syringe, inflate the balloon via the drainage port with 150-500 mL of saline Pack the vagina to avoid expulsion of the tube |

Urologic catheter used for bladder stretching; may be available in the urology department |

| Condom catheter | Slide the condom over the end of the Foley catheter and tie it off with string to close the end Inflate with 250-500 mL of saline and clamp the end Pack the vagina to avoid expulsion of the tube |

A sterile rubber catheter is fitted with a condom |

| Vaginal packing | Pack the vagina with a blood pressure cuff placed inside a sterile glove Increase pressure to 10 mm Hg above systolic blood pressure |

Various techniques have been described; concern for bleeding proximal to the vaginal pack |

| Noninflatable antishock garment | Begin application at the ankles and progress sequentially up to the abdomen | Adjust the panels if any discomfort or dyspnea; contraindicated in women with heart failure or mitral stenosis |

Uterine tamponade with sterile gauze and balloon tamponade are commonly used temporizing measures. Uterine balloon tamponade has been described with large Foley catheters, Sengstaken-Blakemore tubes, condom catheters, sterile gloves, and Rusch urologic catheters, as well as with catheters specifically designed to be used for uterine tamponade in patients with postpartum hemorrhage (SOS Bakri tamponade balloon).10

Uterine Inversion

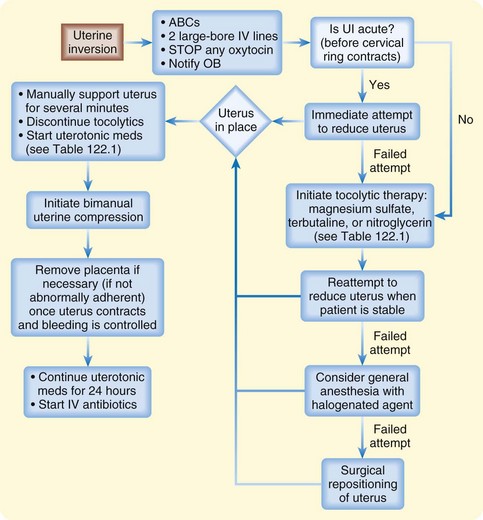

Management of uterine inversion has two important components: treatment of hemorrhagic shock and immediate repositioning of the uterus (Fig. 122.2). Resuscitation should be initiated immediately and continued while attempts are made to reposition the uterus manually. If oxytocin is being infused, it should be stopped once uterine inversion is suspected.

Fig. 122.2 Algorithm for uterine inversion management strategies.

ABCs, Airway, breathing, and circulation; IV, intravenous; OB, obstetrics; UI, uterine inversion.

The success of nonsurgical replacement depends on completion before the myometrium regains its tone. The reported rate of successful immediate reduction is between 40% and 80%.11 If initial measures are delayed or fail to relieve the condition, the inversion may progress to the point at which operative treatment or even hysterectomy is necessary.

The most common nonsurgical replacement method is a variation of the Johnson maneuver.12 The prolapsed uterus is cupped in the operator’s palm, and firm upward pressure is applied to move the uterus up through the cervix along the natural curve of the pelvis toward the umbilicus until it is in place. Usually when the inverted mass is pushed upward, the uterus automatically reverts, with the fundus returning to its anatomic position. If the placenta has not separated, it should not be removed.

If initial repositioning is unsuccessful, myometrial relaxation with pharmacologic agents should be attempted. Magnesium sulfate, terbutaline, and nitroglycerin (attractive because of its easy availability and short half-life) are the agents most commonly used (see Table 122.1).13 Attempts at manual repositioning of the uterus should continue.

Uterine Rupture

For unstable patients, prompt, aggressive resuscitation is an important temporizing measure until definitive surgical repair is performed. Fetal morbidity almost invariably occurs because of catastrophic hemorrhage, fetal anoxia, or both. In a study of 99 cases of uterine rupture, the best fetal outcomes were noted when surgical delivery was accomplished within 17 minutes from the onset of fetal distress.7

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Tips and Tricks

Peripartum Hemorrhage

Use an endotracheal tube 0.5 to 1 mm smaller than you would normally use because the airway may be narrowed from edema.

Compensate for reduced ventilation volumes (because of an elevated diaphragm) with a higher respiratory rate.

The left lateral position, manual uterine displacement, and perimortem cesarean delivery may improve the maternal circulation.

Do not use a femoral vein for a central line.

Follow the standard advanced cardiac life support guidelines for resuscitation, medications, and defibrillation doses (remove any fetal or uterine monitors before defibrillation).

Administer calcium gluconate (1 ampule or 1 g) for arrest from suspected magnesium toxicity.

Perimortem Cesarean Delivery

Epidemiology

Maternal arrest is estimated to occur in 1 in 4000 to 6500 pregnancies in the United States.14–16 In any maternal arrest that occurs beyond 24 weeks’ gestation, perimortem cesarean delivery should be considered as a potentially lifesaving intervention for both the mother and the fetus.17

When comparing causes of death in the cohort of women undergoing perimortem cesarean delivery with all maternal deaths, trauma accounts for a larger proportion in the former group.18 Perimortem cesarean delivery is one of the oldest surgical procedures in history, with the first reference to a successful postmortem cesarean section recorded in 237 BCE.19 Under the emperors of Rome, the Caesars, a law decreeing that a child be excised from the womb of any woman who died late in pregnancy became known as the “lex caesare”—consequently the name cesarean operation. The first documented maternal survival after cesarean delivery was a Swiss woman sectioned by her husband in 1500.

Pathophysiology

Even under ideal conditions, cardiac output from chest compressions in a gravid patient is about 10% of normal. Cardiac output can be improved by displacing the uterus or tilting the patient (left lateral decubitus position); however, a decrease in effective chest compressions occurs with an increase in the patient’s body tilt.20

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Perimortem cesarean delivery is indicated for gravid patients more than 24 weeks pregnant (or the uterine fundus is four fingerwidths above the umbilicus if the gestational age is unknown) if arrest continues after 4 to 5 minutes of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. In a study by Katz et al.,17 among the cases with available data on maternal hemodynamics during resuscitation, more than half the women had a “sudden and often profound improvement, including return of pulse and blood pressure at the time the uterus was emptied.” The study concluded that perimortem delivery should be performed within 4 minutes of maternal arrest if resuscitation was ineffective. An update published in 2005 strongly supported this conclusion,17 and the 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiac arrest associated with pregnancy agree with this window (even sooner if it is clear that the mother has a grave or nonsurvivable injury).21

Treatment

See Box 122.2, “Procedure for Perimortem Cesarean Delivery,” and Fig. 122.3.

Box 122.2 Procedure for Perimortem Cesarean Delivery

Using a No. 10 blade, make a midline vertical incision that goes through all abdominal layers to the peritoneal cavity, which extends from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis.

Separate the rectus muscles in the midline and enter the peritoneum. If available, retractors can be used to expose the anterior surface of the uterus. If the bladder is full, it may be seen inferior to the uterus. A Foley catheter is optimal, but under pressing conditions the bladder can be drained with a small scalpel incision and applied pressure.

To enter the uterus, start with a vertical incision through the lower uterine segment until amniotic fluid is obtained or the uterine cavity is clearly entered. Next, lift the uterine wall away from the fetus with two fingers and use blunt scissors to extend the incision vertically to the fundus; allow generous exposure. The membranes should be ruptured and the baby delivered.

Suction the infant’s mouth and nose, and clamp and cut the cord. If the mother regains stable vital signs, remove the placenta and repair the uterus, abdomen, and bladder.

Amniotic Fluid Embolism

Epidemiology

Amniotic fluid embolism and the resulting anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy occur in late pregnancy or immediately postpartum. Though rare (roughly 1 in 8000 to 80,000 pregnancies), it is responsible for about 10% of all maternal deaths in the United States and is the most common cause of peripartum death.22

Pathophysiology

Despite knowledge of this deadly syndrome for more than 80 years, its cause and pathophysiology are not fully understood. The criteria to make the diagnosis are still controversial, and no management interventions have been proved to improve outcomes or prevent the syndrome.23 The term anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy is considered more appropriate than the term amniotic fluid embolism because of lack of evidence supporting a causative embolic event.24

Anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy, from a clinical, hemodynamic, and hematologic standpoint, is similar to anaphylaxis and septic shock and suggests the possibility of a shared pathophysiologic mechanism.25 The syndrome appears to be initiated after maternal intravascular exposure to fetal tissue. Fetal-maternal tissue transfer is common and probably normal. It is proposed that when fetal antigens breach a maternal immunologic barrier in some women, release of endogenous mediators is triggered, and an anaphylactoid syndrome can occur.24

Neurologic damage is seen in as many as 85% of survivors of anaphylactoid syndrome.25 The mechanism of neurologic injury is thought to be severe hypoxia leading to encephalopathy and seizures. The increased metabolic demand concurrent with seizures (seen in 50%) may worsen the brain injury, especially in the setting of hypoxia.3 Disseminated intravascular coagulation developed within 4 hours of initial evaluation in more than 80% of patients.25 If diffuse bleeding occurs, hemorrhagic shock can contribute to the hypotension.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The National Registry’s criteria for the diagnosis of amniotic fluid embolism are included in Box 122.3. The diagnosis of anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy is one of exclusion. Its dramatic and rapid onset should prompt immediate action; death has been reported in 30 minutes to 7 hours after onset, with most deaths occurring within the first 2 hours. The initial signs and symptoms can be difficult to differentiate from those seen with other serious causes, but management, with a focus on cardiopulmonary stabilization, is similar (Box 122.4).

Box 122.3

National Registry Criteria for the Diagnosis of Amniotic Fluid Embolism

Acute hypotension or cardiac arrest

Acute hypoxia (defined as dyspnea, cyanosis, or respiratory arrest)

Coagulopathy (defined as laboratory evidence of intravascular consumption or fibrinolysis or severe clinical hemorrhage in the absence of other explanations)

Onset during dilation and evacuation, labor, cesarean delivery, or within 30 minutes postpartum

Absence of other significant, confounding conditions or explanation of the symptoms and signs listed here

Modified from Clark SL, Hankins GD, Dudley DA, et al. Amniotic fluid embolism: analysis of the national registry. Am J Obstet Gyrecol 1995;172:1158–69.

Treatment

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Underestimating the degree of blood loss in patients with peripartum hemorrhage or not appreciating moderate-appearing bleeding

Delaying uterine inversion replacement, which increases mortality (increases the risk and degree of hemorrhage and shock) and decreases the likelihood of successful nonsurgical repositioning because of cervical constriction

Not performing emergency cesarean delivery in maternal (>24 weeks of gestation) cardiac arrest not immediately reversed by cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Overlooking intrauterine, intravaginal, intraperitoneal, or retroperitoneal accumulation of blood in a hemodynamically unstable peripartum patient

Presuming that patients with active bleeding are stable because they have normal vital signs

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

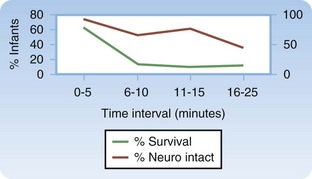

Patients who survive long enough to be transferred to the intensive care unit have a better prognosis, but the overall mortality is reported to be 60%.25 In one study, only 8% of patients who had cardiac arrest as part of the initial findings survived neurologically intact. The infant survival rate was reported to be 70%, but almost half of the survivors had neurologic damage. If arrest occurs, a short arrest-to-delivery interval is associated with improved neonatal outcomes.25

For expanded content on nonvertex presentation in delivery, cord-related complications, shoulder dystocia, premature rupture of membranes and preterm premature rupture of membranes, and multiple gestations, see www.expertconsult.com.

Nonvertex Presentation in Delivery

Epidemiology

Excluding nuchal cord, breech presentation is the most common malpresentation of the fetus. It complicates 4% of all births with a bias toward premature, low-birth-weight infants. Frank breech is the most common, followed by footling and complete. Prolapsed umbilical cord is a dreaded complication of breech presentation and was demonstrated to be a negligible risk with frank breeches, occurred about 5% to 6% of the time with complete breeches, and had an alarming incidence of 15% to 20% with footling breeches.26

Treatment

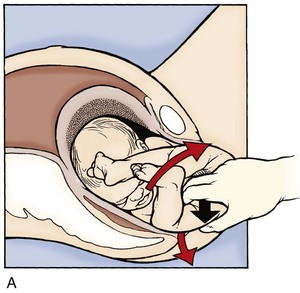

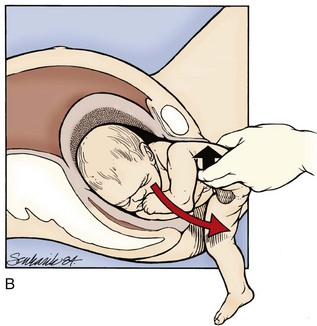

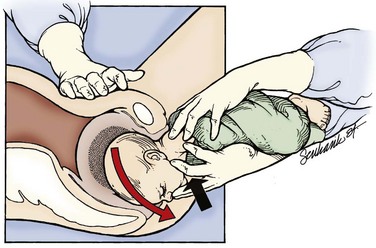

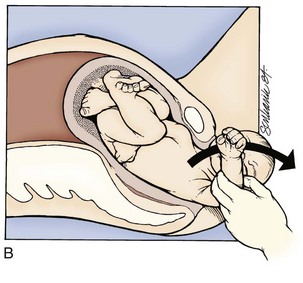

Although they often pass spontaneously, the legs may need assistance to be freed in a frank breech presentation. Once the buttocks have passed through the introitus, the provider frees a given leg by placing two fingers on medial aspect of the thigh and pushes laterally while holding the fetal body stable. This external rotation brings the knee through the introitus and frees the leg. This maneuver is then repeated on the other leg (Fig. 122.4).

No more than gentle downward traction should be applied until the fetal scapulae are visible. At this point, rotation of the fetal torso 90 degrees in one direction should elicit delivery of a shoulder, followed by 180-degree rotation in the other direction for the remaining shoulder (clockwise for the left and counterclockwise for the right) (Fig. 122.5). The goal is to turn the fetus “into” the shoulder that is attempting to be freed. If this maneuver does not free the shoulder, a nuchal arm should be suspected. The physician should attempt to manually splint and sweep the flexed arm over the thorax (in a manner similar to posterior shoulder delivery for shoulder dystocia) to enable its passage. Upper extremity and clavicle fractures are a common complication.

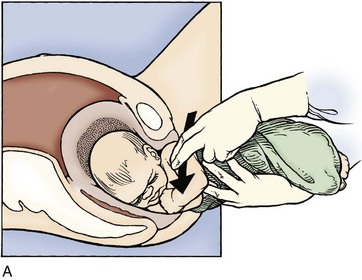

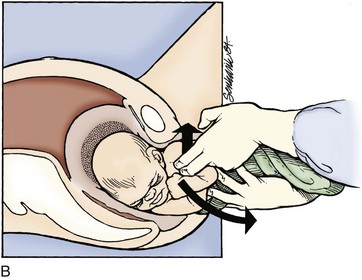

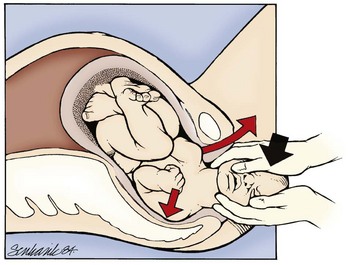

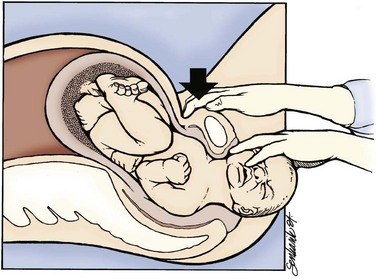

The Mauriceau maneuver (Fig. 122.6) is used if the fetal head fails to pass easily. The physician slips the index and middle fingers under the anterior surface of the fetus and places them against the fetal maxilla. The fetal torso therefore rests on the physician’s forearm with the legs straddling down. The other hand is then inserted over the fetal back to grasp the shoulders and provide downward traction in concert with traction on the maxilla, not the mandible, to keep the fetal head in flexion during its removal. The physician should kneel on one knee while performing this maneuver to be at the level of the maternal pelvis and prevent the tendency to lift the fetus (and extend the neck) while extracting. Ancillary staff may provide suprapubic pressure to assist in this maneuver, which should be performed in tandem with maternal expulsive efforts.

Cord-Related Complications

Epidemiology

Higher rates of prolapse and entanglement are associated with abnormalities in fetal presentation, such as abnormal lie, breech orientation, and compound presentation, with prematurity, and with multiple gestations. A nuchal cord is extremely common, with at least one loop appearing in upward of 30% of pregnancies. This finding alone rarely results in fetal morbidity27 and should perhaps be considered a normal variant.

Treatment

In the case of nuchal or body loops, it should be remembered that a loose loop of cord will probably still have good perfusion. It has been repeatedly demonstrated that a nuchal cord alone does not have a significant impact on fetal outomes.28,29 Therefore, in the absence of arrest of labor or identifiable cord entrapment, the cord should simply be reduced from the fetal neck and labor allowed to proceed as usual. However, excessive manipulation of the cord should be avoided to prevent vasospasm. Once the fetal mouth and nares are suctioned and spontaneous respirations are initiated, the cord may be clamped and separated from the neonate in the usual fashion.

Shoulder Dystocia

Epidemiology

Shoulder dystocia is recorded to occur in anywhere from 0.2% to 3% of all births—the variance being caused by discordant definitions of this condition. Spong et al. proposed criteria that include greater than a 60-second delay between delivery of the fetal head and delivery of the body or the use of ancillary delivery maneuvers,30 but this was found to prospectively identify only 72% of cases of shoulder dystocia.31

Many risks for shoulder dystocia have been proposed, including (but not limited to) fetal macrosomia, maternal diabetes, maternal obesity, and previous history of dystocia. However, most studies that have posited these risk factors for dystocia are retrospective and are not borne out prospectively. The most consistent risk factor is fetal macrosomia—based on actual, not estimated weight. Still, even for neonates weighing more than 4000 g at delivery, shoulder dystocia will complicate only 3.3% of deliveries.32

Although its occurrence can be terrifying, death from dystocia is relatively rare. One study showed the approximate incidence of fatal shoulder dystocia to be 0.025 per 1000 deliveries.33 The most common injury associated with shoulder dystocia is brachial plexus palsy, which has been reported in up to 20% of deliveries involving shoulder dystocia. Thankfully, the large majority of these palsies are transient.

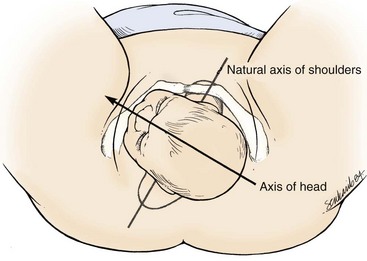

Pathophysiology

In shoulder dystocia, the fetal shoulders fail to clear the pelvis properly. The fetus assumes a position that places the shoulders in an anteroposterior plane between the pubis and sacrum, whereas in a normal delivery they are slightly oblique from this orientation (Fig. 122.7). This abnormal position forces the fetus to pass through a narrower pelvic diameter, which results in shoulder impaction. Most of the time the impaction occurs when the anterior shoulder fails to clear the pubis. Maneuvers that augment these impactions are the basis of treatment.

Treatment

If the anterior shoulder does not deliver spontaneously, the provider may grasp both fetal parietal eminences and provide downward shifting motion traction to “slip” the shoulder under the pubis. A rotary, fulcrum, or bending motion that brings one fetal ear closer to the ipsilateral shoulder should be avoided to prevent brachial plexus injury (Fig. 122.8).

The delivering physician should exert mild downward traction on the fetal head while keeping the cervical spine in line. This maneuver prevents use of the head as a fulcrum to “pry” the shoulder free, which could lead to stretching of the fetal neck and brachial plexus. If this does not result in fetal progression, the McRoberts maneuver should be performed next. Ancillary staff should provide suprapubic pressure concurrently. The McRoberts maneuver (Fig. 122.9) is performed by tightly flexing the maternal hips or knees to “pull” the pubis back over the anterior fetal shoulder, ideally inducing its passage. This maneuver is favored first by most clinicians because of its simplicity and effectiveness—retrospective studies, however, indicate it works approximately 40% of the time.34 These studies have shown that if this maneuver is combined with suprapubic pressure, the success rate climbs to between 54% and 59%.35 Suprapubic pressure ( Fig. 122.10) is intended to aim a force directly over the site of the impacted anterior shoulder and assist it in sliding beneath the pubis.

Fig. 122.10 Moderate suprapubic pressure will often disimpact the anterior shoulder.

(From Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, et al. Obstetrics—normal and problem pregnancies. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2007.)

Fundal pressure has not been shown to be effective in disimpacting a shoulder and should not be used. If the mother is clinically stable and there is a stable surface on which to perform it, the “all-fours” or “Gaskin” position may be attempted. The reversal of gravitational force combined with altered pelvic dimensions may result in disimpaction—50% of cases in one series were managed by this technique alone.36 The aforementioned maneuvers may be repeated in this position.

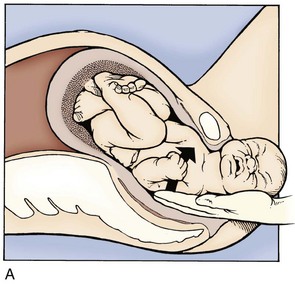

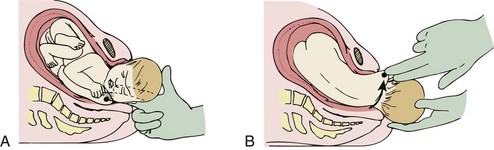

If these techniques are not successful, the physician should attempt a Woods screw or Rubin maneuver. In the Woods screw maneuver the physician palpates the posterior shoulder and exerts a force on its anterior side to effect a rotation. This brings the posterior shoulder around to the anterior side, which both frees the anterior shoulder and aligns both shoulders in the ideal oblique pelvic plane. The Rubin maneuver (Fig. 122.11) is another rotational technique that is the reverse of the Woods screw maneuver: pressure is applied from the posterior side of whichever shoulder is reachable until fetal axial rotation occurs. Some inward pressure on the fetal head (into the vagina) may be required to disimpact a wedged shoulder before these techniques are used. The decision to perform either maneuver should be based on accessibility of the fetus and clinical response to their implementation.

Fig. 122.11 Rubin or reverse Wood screw maneuver for shoulder dystocia.

A, Rotate the posterior shoulder. B, Deliver the rotated shoulder.

(From Roberts JR, Hedges JR. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009.)

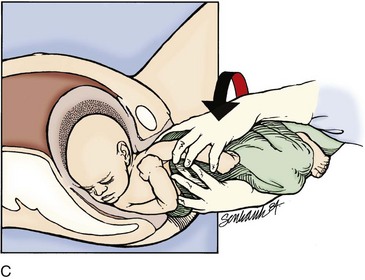

If these maneuvers fail, delivery of the posterior arm should be attempted. This should be the last intrapelvic maneuver attempted given its high association with fetal injury. Delivery of the posterior shoulder aims to reduce the bisacromial diameter (shoulder width) of the fetus, thereby returning the fetus to a dimension that can pass through the pelvis. This maneuver is technically difficult, and clavicular and humeral fractures with associated nerve damage may occur. The physician locates the posterior arm and first flexes the forearm with pressure applied into the acromioclavicular fossa. The flexed arm is then adducted over the chest of the fetus and out of the maternal pelvis (Fig. 122.12). If labor does not proceed with this maneuver alone, it may be combined with one of the aforementioned rotary techniques.

If access to the intrapelvic fetal body is suboptimal, an episiotomy is indicated. However, it is important to note that episiotomy is no longer routinely recommended during delivery. Management by episiotomy or proctoepisiotomy has been associated with a nearly sevenfold increase in the rate of severe perineal trauma without the benefit of reducing the occurrence of neonatal depression or brachial plexus palsy.37 Because of these findings, episiotomy is now recommended only on a clinical as-needed basis to perform maneuvers required to disimpact the fetal shoulders. Episiotomy alone will not alleviate the dystocia because it does nothing to correct the underlying impaction of the shoulder on the pelvis—it merely provides improved access to the fetal body to perform manipulations required to complete delivery. To perform an episiotomy, the vaginal fourchette and perineum are first anesthetized with 1% to 2% lidocaine. The physician’s fingers are used to both expose the area to be incised and provide a physical block between the scissors and the delivering fetus. The scissors are then used to incise through about one half of the perineum. Care must be taken to try to avoid extending into the anal sphincter or, worse yet, into the anal mucosa and cause third- or fourth-degree lacerations, respectively.

Premature Rupture of Membranes and Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes

Management and Disposition

Beyond recognition of PROM and PPROM, the most important intervention is to abstain from a digital vaginal examination. The risk for chorioamnionitis after premature membrane rupture appears to be directly related to the number of examinations performed. Recent data suggest that there is no increase in infectious complications if the number of examinations is less than two.38 Nevertheless, only a sterile speculum examination should be performed in the ED.

Nitrazine testing of vaginal fluid may be performed because of its speed and simplicity. This information may be helpful for the consulting obstetrician but will probably not change management in the ED. Most EDs are equipped with Nitrazine, typically for ophthalmologic evaluation, and performance and interpretation of this test can take place at the point of care. The vagina is typically an acidic environment, so a pH higher than 6.5 is consistent with ruptured membranes. Published sensitivities for this test range from 77% to 92%,39,40 with false results most commonly being caused by inadequate samples or the presence of blood or bacterial infection of the vagina.41 Many EDs do not have a microscope easily available, and thus testing for ferning of the suspect fluid may be impractical.

Particular attention should be focused on evaluating for chorioamnionitis. If maternal fever or unexplained tachycardia is present, the clinical examination should focus on other signs or symptoms of chorioamnionitis. For fetuses younger than 34 weeks and potentially as late as 37 weeks, prophylactic antibiotic administration for PPROM has significantly improved outcomes.42 For patients after 37 weeks, who by definition have PROM, the question of antibiotics is less clear. Unless clear evidence of infection or sepsis is present, consultation with the obstetrician before administering antibiotics is prudent.

Multiple Gestations

Pathophysiology

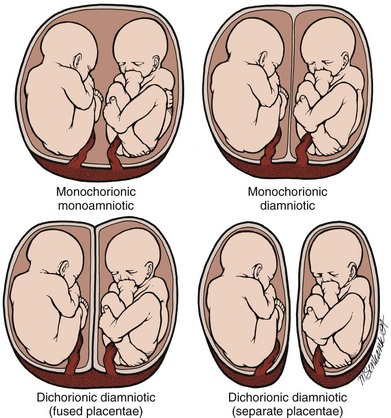

During gestation the fetus is surrounded by two separate membranes—the outer chorion and the inner amnion. This anatomic arrangement can be altered in the case of multiple gestations (twins, the most common multiple gestation, will serve as the reference point here) (Fig. 122.13).

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Twin A will be in a vertex position about 80% of the time, with twin B being in vertex only half as often.43 Therefore, one must not only anticipate the high likelihood of prematurity associated with multiple gestations but must also be prepared for the potential for a nonvertex delivery for twin B.

Treatment

If twin A is nonvertex, every effort should be made to delay labor until a cesarean section can be performed. If twin A is vertex and B is not, attempted vaginal delivery is recommended if the estimated fetal birth weight (EFW) is greater than 2000 g.44,45 However, EFW measurements are not routinely performed in the ED, nor are continuous monitoring modalities or providers experienced in twin deliveries available. Therefore, the clinical status of the second twin and the availability of obstetric assistance should be used to decide the best course of action for twin B. The delay between delivery of twin A and twin B may be fortuitous and provide the needed time for obstetric assistance to arrive and assume care. If no help is available and crowning is occurring, the nonvertex twin B should be handled as any other nonvertex delivery.

1 Brunette DD, Sterner SP. Prehospital and emergency department delivery: a review of eight years experience. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:1116–1118.

2 Mayerhofer K, Bodner-Adler B, Bodner K, et al. Traditional care of the perineum during birth: a prospective, randomized, multicenter study of 1,076 women. J Reprod Med. 2002;47:477–482.

3 Berg CJ, Chang J, Callaghan WM, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1991–1997. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:289–296.

4 McCormick ML, Sanghvi HC, Kinzie B, et al. Preventing postpartum hemorrhage in low-resource settings. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;77:267–275.

5 ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists, Number 76, October 2006: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1039–1047.

6 You WB, Zahn CM. Postpartum hemorrhage: abnormally adherent placenta, uterine inversion, and puerperal hematomas. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49:184–197.

7 Leung AS, Leung EK, Paul RH. Uterine rupture after previous cesarean delivery: maternal and fetal consequences. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:945–950.

8 Fuchs K, Peretz BA, Marcovici R, et al. The “grand multipara”—is it a problem? A review of 5785 cases. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1985;23:321–326.

9 Ripley DL. Uterine emergencies. Atony, inversion, and rupture. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1999;26:419–434.

10 Condous GS, Arulkumaran S, Symonds L, et al. The “tamponade test” in the management of massive postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:767–772.

11 Brar HS, Greenspoon JS, Platt LD, et al. Acute puerperal uterine inversion. New approaches to management. J Reprod Med. 1989;34:173–177.

12 Johnson AB. A new concept in the replacement of the inverted uterus and a report of nine cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1949;57:557–562.

13 Morini A, Angelini R, Giardini G. Acute puerperal uterine inversion: a report of 3 cases and an analysis of 358 cases in the literature. Minerva Ginecol. 1994;46:115–127.

14 Deneux-Tharaux C, Berg C, Bouvier-Colle MH, et al. Underreporting of pregnancy-related mortality in the United States and Europe. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:684–692.

15 Horon IL, Cheng D. Underreporting of pregnancy-associated deaths. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1879. author reply 1879–80

16 Horon IL. Underreporting of maternal deaths on death certificates and the magnitude of the problem of maternal mortality. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:478–482.

17 Katz V, Balderston K, DeFreest M. Perimortem cesarean delivery: were our assumptions correct? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1916–1920.

18 Kloeck W, Cummins RO, Chamberlain D, et al. Special resuscitation situations: an advisory statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Circulation. 1997;95:2196–2210.

19 Whitten M, Irvine LM. Postmortem and perimortem caesarean section: what are the indications? J R Soc Med. 2000;93:6–9.

20 Rees GA, Willis BA. Resuscitation in late pregnancy. Anaesthesia. 1988;43:347–349.

21 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Part 12.3: cardiac arrest associated with pregnancy. Circulation. 2010;122:S829–S861.

22 Clark SL, Hankins GD, Dudley DA, et al. Amniotic fluid embolism: analysis of the national registry. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:1158–1169.

23 Moore J, Baldisseri MR. Amniotic fluid embolism. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(10 Suppl):S279–S285.

24 Azegami M, Mori N. Amniotic fluid embolism and leukotrienes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155:1119–1124.

25 Locksmith GJ. Amniotic fluid embolism. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1999;26:435–444.

26 Collea JV, Rabin SC, Weghorst GR, et al. The randomized management of term frank breech presentation: vaginal delivery vs cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1978;131:186–195.

27 Clapp III, JF., Stepanchak W, Hashimoto K, et al. The natural history of antenatal nuchal cords. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:488–493.

28 Schaffer L, Burkhardt T, Zimmermann R, et al. Nuchal cords in term and postterm deliveries—do we need to know? Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:23–28.

29 Mastrobattista JM, Hollier LM, Yeomans ER, et al. Effects of nuchal cord on birthweight and immediate neonatal outcomes. Am J Perinatol. 2005;22:83–85.

30 Spong CY, Beall M, Rodrigues D, et al. An objective definition of shoulder dystocia: prolonged head-to-body delivery intervals and/or the use of ancillary obstetric maneuvers. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:433–436.

31 Beall MH, Spong C, McKay J, et al. Objective definition of shoulder dystocia: a prospective evaluation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:934–937.

32 Kolderup LB, Laros Jr, RK., Musci TJ. Incidence of persistent birth injury in macrosomic infants: association with mode of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:37–41.

33 Hope P, Breslin S, Lamont L, et al. Fatal shoulder dystocia: a review of 56 cases reported to the Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:1256–1261.

34 Gherman RB, Goodwin TM, Souter I, et al. The McRoberts’ maneuver for the alleviation of shoulder dystocia: how successful is it? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:656–661.

35 McFarland MB, Langer O, Piper JM, et al. Perinatal outcome and the type and number of maneuvers in shoulder dystocia. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1996;55:219–224.

36 Bruner JP, Drummond SB, Meenan AL, et al. All-fours maneuver for reducing shoulder dystocia during labor. J Reprod Med. 1998;43:439–443.

37 Gurewitsch ED, Donithan M, Stallings SP, et al. Episiotomy versus fetal manipulation in managing severe shoulder dystocia: a comparison of outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:911–916.

38 Alexander JM, Mercer BM, Miodovnik M, et al. The impact of digital cervical examination on expectantly managed preterm ruptured membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1003–1007.

39 Kishida T, Hirao A, Matsuura T, et al. Diagnosis of premature rupture of membranes with an improved alpha-fetoprotein monoclonal antibody kit. Clin Chem. 1995;41:1500–1503.

40 Rochelson BL, Rodke G, White R, et al. A rapid colorimetric AFP monoclonal antibody test for the diagnosis of preterm rupture of the membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69:163–165.

41 Smith R. A technic for the detection of rupture of the membranes: a review and preliminary report. Obstet Gynecol. 1976;48:172–176.

42 Mercer BM, Miodovnik M, Thurnau GR, et al. Antibiotic therapy for reduction of infant morbidity after preterm premature rupture of the membranes. A randomized controlled trial. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. JAMA. 1997;278:989–995.

43 Chervenak FA, Johnson RE, Youcha S, et al. Intrapartum management of twin gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;65:119–124.

44 Fishman A, Grubb DK, Kovacs BW. Vaginal delivery of the nonvertex second twin. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:861–864.

45 Greig PC, Veille JC, Morgan T, et al. The effect of presentation and mode of delivery on neonatal outcome in the second twin. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:901–906.