16 Emergencies in Infants and Toddlers

• Use a systematic approach to evaluate and manage infants and toddlers. Know common milestones and age-specific manifestation of illness, take an “AMPLIFIEDD” history, do a “head-to-toe” physical examination, and use the “head-to-toe” memory tool to generate an expanded differential diagnosis.

• Do not make the diagnosis of infantile colic on first episode of excessive crying. Remember Wessel’s rule of 3.

• When the cause of illness in an infant or toddler is not obvious, the emergency practitioner should maintain a high level of suspicion for abuse, accidental toxin ingestion or exposure, intussusception, infection, and nonconvulsive seizure activity.

Perspective

More than 20% of emergency department (ED) visits are by pediatric patients, and a large proportion involve children 4 years or younger.1,2 Common reasons for ED visits in this age group include traumatic injuries, fever, respiratory complaints, and gastrointestinal problems.3–5 Although many of the disease processes are self-limited, it is imperative that the emergency practitioner (EP) identify infants and children at risk for progression to serious illness.

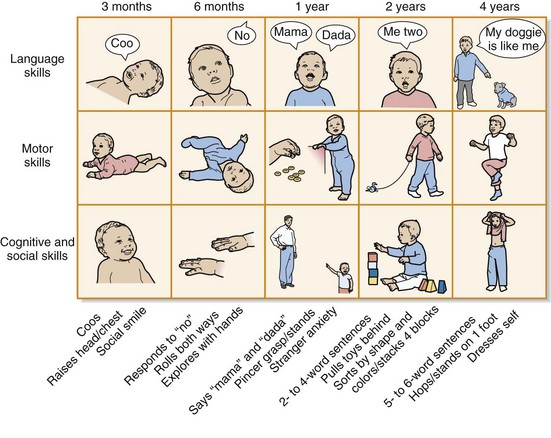

Knowledge of developmental milestones and age-specific manifestations of illness, in addition to taking a thorough history and physical examination, will greatly enhance the clinician’s ability to diagnose and initiate appropriate therapeutic interventions. From early infancy to the toddler stage, remarkable developmental changes occur. Understanding the changes in language, motor, cognitive, and social skills is important to properly assess infants and toddlers (Fig. 16.1). Many of the common illnesses experienced are age related (Table 16.1), and early recognition of the signs and symptoms of the specific diseases that threaten infants and toddlers is an effective strategy. Taking an “AMPLIFIEDD” history (Box 16.1) and performing a “head-to-toe” physical examination allow the clinician to gather the clinical clues needed to generate a comprehensive differential diagnosis. Practitioners in the ED are encouraged to develop an expanded differential diagnosis by using their knowledge of anatomy to aid memory (Table 16.2).

Table 16.1 Age-Related Differential Diagnosis for Various Chief Complaints (Overlap Can Occur)

| INFANTS | TODDLERS | |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory Complaints | ||

| Cough | ||

Box 16.1 The “AMPLIFIEDD” History

Allergies: to medications, environmental allergens

Medications: prescription, over the counter, natural remedies

Past medical or surgical history:

Last “feed, pee, poop”: Feeding, stool, and urine pattern; use of formula (dilution?)

Immediate events (history of present illness and review of systems): OLD CAARS

Emergency medical service history: Elicit history of potential trauma, ingestion, abuse, or toxin exposure

Doctor: Name of primary care physician or specialist for additional information and help

Table 16.2 The “Head-to-Toe” Memory Tool

| “HEAD-TO-TOE” PHYSICAL EXAMINATION | POTENTIAL CLINICAL FINDINGS | GENERATE “HEAD-TO-TOE” DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS (EXAMPLES) |

|---|---|---|

| Head | Bulging fontanelle Step-off, laceration, ecchymosis, hematoma Ventriculoperitoneal shunt |

|

| Eyes | Icterus, conjunctival injection, cranial nerve deficit, retinal hemorrhage | |

| Nose | Congestion | |

| Mouth | Poor dentition | |

| Neck | Mass | |

| Chest Pulmonary Cardiac |

Chest wall tenderness Stridor, rales, rhonchi, wheezing, murmur, dysrhythmia |

|

| Abdomen Gastrointestinal tract Liver Pancreas Kidney and urinary tract Adrenal glands |

Distention, tenderness, peritoneal signs, palpable mass | |

| Extremities | Deformity, tenderness, edema, induration, erythema | |

| Skin | Rash, petechiae | |

| Neurologic | Weakness, decreased reflexes |

The Crying Infant

Perspective

One of the most challenging aspects of pediatric emergency care is managing an infant with the nonspecific symptom of acute, excessive crying. Infants are not able to vocalize complaints, and crying is the primary mode of communication until language development. According to Brazelton, most babies will cry between  and 3 hours per day in the first 3 months of life, with the peak occurring at approximately 6 weeks.7 By the time that parents bring their crying infant or toddler to the ED, they are often exhausted from attempts to console the child. In such circumstances, the EP must be able to distinguish between relatively benign conditions, such as colic, and severe, life-threatening illnesses, such as meningitis. An orderly approach to infants with excessive unexplained crying will allow the EP to diagnose the occasional severe illness and provide guidance to the caregivers.

and 3 hours per day in the first 3 months of life, with the peak occurring at approximately 6 weeks.7 By the time that parents bring their crying infant or toddler to the ED, they are often exhausted from attempts to console the child. In such circumstances, the EP must be able to distinguish between relatively benign conditions, such as colic, and severe, life-threatening illnesses, such as meningitis. An orderly approach to infants with excessive unexplained crying will allow the EP to diagnose the occasional severe illness and provide guidance to the caregivers.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of early excessive crying (e.g., >3 hours) in infants younger than 3 months has been estimated at 8% to 29%, but it may persist for months longer in up to 40% of these children.8 However, there is no accurate estimate of the incidence of excessive crying secondary to illness because almost every disease process can be accompanied by the symptom of crying. As infants grow and expand their repertoire for expressing specific needs, excessive crying is less frequently voiced as a primary complaint by caregivers.

Pathophysiology

During the first few months of life, infants are expected to have variable periods of prolonged crying, which is normal behavior. However, crying is considered excessive when parents complain about it. Most paroxysmal episodes of crying have a behavioral etiology. In 1954 Wessel published his “rule of 3” for diagnosing colic: when an otherwise healthy infant between the ages of 3 weeks and 3 months cries more than 3 hours per day for more than 3 days per week.9 However, if organic pathology is to be identified, the EP must recognize that excessive crying has meaning and may be indicative of acute illness. In a study of 56 infants with an episode of excessive, prolonged crying without fever or cause identified by the parents, 61% had a serious final diagnosis.10

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

After the primary survey is complete and it is determined that no emergency intervention is indicated, the EP needs to elicit a comprehensive AMPLIFIEDD history (Box 16.2) from the primary caregiver. Clinical findings on the head-to-toe evaluation suggesting a potential cause of the excessive crying may include the following:

• Signs of head trauma, such as scalp contusions, ecchymoses and lacerations, hemotympanum, postauricular hematomas, or periorbital ecchymoses

• A bulging fontanelle indicative of increased intracranial pressure

• A sunken anterior fontanelle consistent with dehydration

• Fluorescein uptake indicating corneal abrasions

• Retinal hemorrhages raising concern for serious abuse

• An erythematous and bulging tympanic membrane signifying otitis media

• Obstruction of the nares secondary to a foreign body

• Oral thrush or mucosal ulcers in the oropharynx often seen with stomatitis

• Exudative pharyngitis and fullness of the posterior pharynx suggesting peritonsillar or retropharyngeal abscesses

• Wheezing, rales, or rhonchi indicating a respiratory infection

• Palpation of a mass during the abdominal examination, which can be associated with pyloric stenosis, intussusception, or a tumor

• Diaper rash, anal fissure, or impacted stool on rectal examination

• Scrotal swelling consistent with an incarcerated hernia or testicular torsion

• Extremity tenderness, edema, or bruising concerning for a possible fracture

• Erythema, induration, and tenderness suggesting a soft tissue infection (cellulitis or abscess)

• Hair tourniquet on a toe or finger

• Rashes with potentially life-threatening causes (e.g., petechiae, purpura)

Box 16.2 The AMPLIFIEDD History for a Crying Infant or Toddler

Medication (by mom or infant): Prescription, over the counter, natural remedies

Immediate events (history of present illness and review of systems): OLD CAARS

Immunizations: Nonstop crying episodes for longer than 3 hours can rarely occur with recent pertussis vaccination*

Emergency medical service history: Elicit history of potential trauma, abuse, or toxin exposure

Doctor: Name of primary care physician or specialist for additional information and help

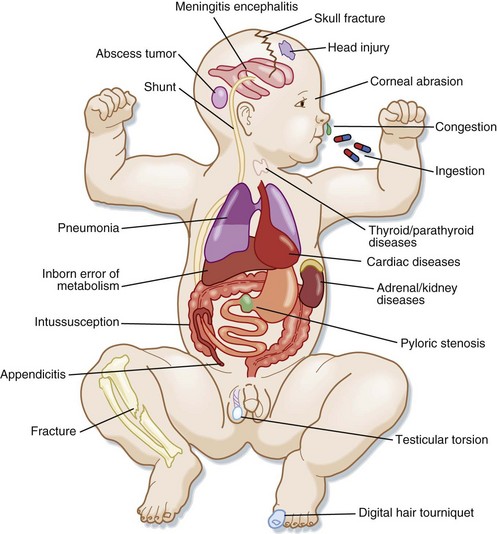

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

A comprehensive history and systematic head-to-toe physical examination along with a period of ED observation are usually sufficient to differentiate acute illness or injury from a recurrent benign crying syndrome. It is important to remember that excessive crying may be the only behavioral change that the caregiver recognizes as an indicator of illness. Detection of subtle signs and symptoms will help identify high-acuity, low-frequency events. The practitioner should pay close attention to red flags in a young infant such as fever, failure to thrive, paradoxic irritability (crying with movement), vomiting, bloody stools, abnormal neurologic findings, and unexplained abnormal vital signs. A comprehensive differential diagnosis can be generated by using the head-to-toe memory tool (Fig. 16.2 and Box 16.3).

Box 16.3 Differential Diagnosis of Crying (Head-to-Toe Memory Tool)

Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, and Mouth

Head: Meningitis, encephalitis, ventriculoperitoneal shunt malfunction or infection, closed head injury (skull fracture; epidural, subdural hematoma), cerebrovascular accident, tumor

Eye: Foreign body, corneal abrasion, glaucoma

Nose: Nasal congestion (distress in those <6 mo)

Mouth: Ingestion (drug toxicity such as carbon monoxide, methemoglobinemia), thrush, stomatitis

Abdomen

Gastrointestinal tract: Gastroesophageal reflux, aerophagia, pyloric stenosis, intussusception, malrotation with volvulus, inguinal hernia, gastroenteritis with dehydration, appendicitis, Hirschsprung disease, constipation, peritonitis

Liver: Inborn errors of metabolism

Pancreas: Hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis

Kidney and urinary tract: Electrolyte disorders, urinary tract obstruction, urinary tract infection, torsion of the testes or ovaries, hair tourniquet of the penis

Allow the history, physical examination, and observed behavior of the infant to guide a stepwise approach to diagnostic evaluation. A healthy-appearing infant who ceases crying before or soon after arrival at the ED rarely has a serious cause.11 An infant who continues to cry will require diagnostic testing directed by careful consideration of the potential differential diagnosis (Box 16.4). For example, suspicion of child abuse should prompt a funduscopic examination and consideration of radiographic studies, including a skeletal survey, computed tomography (CT) of the head, and CT of the abdomen and pelvis. Evaluate cardiac problems with continuous cardiac monitoring, a 12-lead electrocardiogram, a chest radiograph, and an echocardiogram as indicated. Confirm gastrointestinal pathology with selective radiographic studies such as screening supine and upright abdominal radiographs, ultrasound, upper gastrointestinal series, or judicious use of CT scanning. Evaluate for infectious causes with a chest radiograph, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, and urinalysis. Serum electrolytes, ammonia level, serum pH, and lactate levels are useful to screen for an inborn error of metabolism. Use C-reactive protein, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, bone scanning, and magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate potential musculoskeletal pathologies.

Treatment and Disposition

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Do not make a diagnosis of infantile colic on the first episode of excessive crying. Remember Wessel’s rule of 3.9

Paradoxic irritability (crying with movement) and an acute onset of unexplained crying are red flags for serious illness.

Always undress the infant or child and document a rectal temperature.

Initiate a period of observation if the infant does not appear to be ill. Proceed with a further diagnostic work-up if the crying does not cease.

In a child who will be discharged home, document and review plans for followup and mandate return to the emergency department if the symptoms return or progress.

Altered Level of Consciousness

Epidemiology

An altered level of consciousness in this age group is caused by nonstructural causes (e.g., infection, metabolic abnormalities, toxin ingestion) or primary structural disease of the CNS (e.g., hemorrhage, tumors). Physical abuse is the leading cause of serious head injury in young children. Shaken baby syndrome most often involves children younger than 2 years and can easily be misdiagnosed.12

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Always direct the initial evaluation toward identifying potential life-threatening conditions such as hypoxia, hypotension, extremes of temperature, hypoglycemia, seizure activity, and increased intracranial pressure, which require immediate intervention. Once these issues have been excluded, the EP should perform an AMPLIFIEDD history (Box 16.5). Investigate the risk for accidental or nonaccidental trauma, infection, ingestion, or toxin exposure while identifying signs or symptoms suggestive of systemic disease. Interview all available caretakers and emergency medical service personnel.

Box 16.5 The AMPLIFIEDD History for an Infant or Toddler with Altered Level of Consciousness

Allergies to medications, environmental allergens

Medications: prescriptions, over the counter, natural remedies

Past medical history: Birth history, congenital anomalies, chronic disease (e.g., inborn error of metabolism, endocrinopathy), infections, seizures

Last feed, pee, poop: Feeding, stool and urine pattern, use of formula (dilution?)

Immediate events (history of present illness and review of systems): OLD CAARS

Family and social history: Inherited disorders, day care, who cares for the child

Emergency medical system history: Elicit history of potential trauma, ingestion, abuse, or toxin exposure

Doctor: Name of primary care physician or specialist for additional information and help

Following the primary survey, a head-to-toe evaluation should be performed. The EP should:

• Pay close attention to the pupillary response, which generally remain intact with metabolic insults but may be absent with structural lesions, toxin exposure, or severe asphyxia.

• Note the eye position (e.g., deviation of conjugate gaze away from brainstem lesions and toward cerebral lesions).

• Identify abnormalities in the respiratory pattern that may reflect CNS insults or metabolic conditions such as metabolic acidosis.

• Evaluate motor strength, tone, and reflexes, and characterize activity that may be consistent with seizures or abnormal posturing.

• Look for signs of trauma, such as scalp contusions and lacerations, hemotympanum, postauricular or periorbital hematomas, retinal hemorrhages, cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea, and a bulging anterior fontanelle suggestive of increased intracranial pressure.

• Note odors suggesting inborn errors of metabolism or other metabolic disorders (e.g., the smell of acetone in a child with diabetic ketoacidosis).

• Identify physical findings that indicate systemic infections involving the CNS (e.g., vesicular or purpuric rashes).

• Identify signs of other systemic disorders that have a negative impact on mental status, such as intussusception (e.g., abdominal mass, blood in the stool), hepatic disorders (e.g., jaundice, icterus), or cardiopulmonary disease (e.g., hypoxia, rales, hepatomegaly).

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

A comprehensive differential diagnosis for alterations in consciousness in infants and toddlers can be generated with the head-to-toe memory tool (Box 16.6). Possible causes involve essentially every organ system. When the underlying cause of altered mental status is not obvious, a high level of suspicion should be maintained for abuse, accidental toxin ingestion or exposure, intussusception, infection, or nonconvulsive seizure activity.

Box 16.6 Differential Diagnosis of Altered Level of Consciousness in Infants and Toddlers Using the Head-to-Toe Memory Tool

Head and Mouth

Abdomen

Gastrointestinal tract: Intussusception, dehydration secondary to vomiting, diarrhea

Liver: Inborn errors of metabolism, Reye syndrome, hepatic encephalopathy

Perform laboratory and radiographic testing via a systematic, comprehensive approach (Box 16.7). In a critically ill infant or toddler without a definitive diagnosis, routine testing for sepsis, trauma, and metabolic derangements should be supplemented with selective tests as dictated by progression of the clinical course, by the response to initial interventions, and by the history and physical findings.

Box 16.7 Laboratory and Radiographic Testing in Infants and Toddlers with Altered Level of Consciousness

Vomiting

Epidemiology

Episodes of acute gastroenteritis in children younger than 5 years lead to 2 to 3 million physician visits annually.13 The majority of these children have uneventful clinical courses.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

A review of the expansive list of potential causes of vomiting emphasizes the importance of developing an organized approach to achieve an accurate diagnosis. The EP should first elicit an AMPLIFIEDD history (Box 16.8) and perform a thorough head-to-toe physical examination focusing on the age of the infant or toddler. Evidence of bowel obstruction, peritonitis, and signs or symptoms suggestive of extraintestinal disease should be sought. Hydration status (Box 16.9) should be assessed. At the onset of the clinical encounter, the EP should clarify whether the child has had bilious or nonbilious vomiting because bilious emesis in infants implies intestinal obstruction until proved otherwise and requires immediate surgical consultation.14

Box 16.8 The AMPLIFIEDD History for an Infant or Toddler with Vomiting

Allergies: To medications or foods ( protein intolerance to cow milk, soy, gluten)

Medication: Prescription, over the counter, natural remedies

Immediate events (history of present illness and review of systems): OLD CAARS

Emergency medical service history: Elicit history of potential trauma, ingestion, abuse, or toxin exposure

Doctor: Name of primary care physician or specialist for additional information and help

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The list of potential causes of vomiting in infants is extensive but can be conveniently organized according to age-related categories (Table 16.3). Many serious medical conditions may be initially manifested as vomiting, such as sepsis, meningitis, urinary tract infection, and hepatitis. These conditions must be differentiated from emergency surgical conditions such as an incarcerated hernia, intussusception, and malrotation with volvulus. Intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in children 3 months to 5 years of age, whereas appendicitis is the most common condition requiring surgical intervention.15,16

Table 16.3 Differential Diagnosis of Vomiting in Infants and Children Using the Head-to-Toe Memory Tool

| INFANTS | TODDLERS | |

|---|---|---|

| Head |

The large number of potential causes of vomiting makes routine laboratory and radiographic evaluation impractical. The history and physical findings should direct the choice of testing for each patient. For most common conditions, laboratory testing is not indicated. A bedside blood glucose measurement should be performed in any child with altered mental status. Serum electrolytes should be measured in children with dehydration requiring intravenous rehydration. A serum bicarbonate level lower than 17 mEq/L appears to be the most useful laboratory value for predicting the likelihood of 5% dehydration.17,18 Cerebrospinal fluid analysis should be performed if meningitis or encephalitis is suspected. Drug screening may be necessary to confirm an ingestion. Urinalysis, liver function tests, serum lipase, and ammonia measurements should be considered when the differential diagnosis is broadened.

Diagnostic imaging is also dictated by clinical findings. CT of the head should be performed for suspected closed-head injury, intracranial tumor, or hydrocephalus. Plain radiographs may be used to assess for bowel obstruction. An upper gastrointestinal series is the preferred radiographic modality for diagnosing malrotation with volvulus.19 Diagnostic ultrasonography is the modality of choice for diagnosing intussusception.20 Ultrasonography and abdominal CT are used to investigate potential appendicitis when the diagnosis is in question. In children with equivocal findings for appendicitis, ultrasonography using the graded-compression technique should be performed, followed by focused abdominal CT if the ultrasonographic findings are normal.21 Similarly, implement protocols for appropriate use of ultrasonography and CT for evaluation of intraabdominal pathology such as trauma, an intraabdominal mass, or nephrolithiasis.

Treatment

Administration of an antiemetic may serve as a successful adjunct to suppress vomiting and allow oral rehydration. Intravenous and oral ondansetron (a selective serotonin [5-HT3] receptor antagonist) has been used successfully in the ED for infants and children with vomiting secondary to gastroenteritis.22–24

Oral rehydration therapy should be administered to children with mild to moderate dehydration as a result of gastroenteritis (Box 16.10).25 A metaanalysis of randomized control trials involving 1545 children younger than 15 years concluded that rehydration by the oral or nasogastric route is as effective if not better than intravenous rehydration.26

Box 16.10

Oral Rehydration Therapy

Rehydration Phase

Replace fluid deficit over a 4-hour period with rehydration solution (Rehydralyte, Pedialyte)

Administer oral rehydration therapy in frequent, small amounts: no more than 5 mL every 1 to 2 minutes via syringe, spoon, cup, or nasogastric tube

Goal: 50 mL/kg for mild dehydration, 100 mL/kg for moderate dehydration

Replace ongoing losses from diarrhea (10 mL/kg per watery stool) and vomiting (2 mL/kg per episode of emesis) with oral rehydration solution

Avoid nonphysiologic foods such as juice, tea, and cola during this phase

Data from Practice parameter: The management of acute gastroenteritis in young children. American Academy of Pediatrics, Provisional Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Acute Gastroenteritis. Pediatrics 1996;97:428-9.

1 Nawar EW, Niska RW, Xu J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2005 Emergency Department Summary. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics, 386. National Centers for Health Statistics; 2007.

2 Shah MN, Cushman JT, Davis CO, et al. The epidemiology of emergency medical services use by children: an analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008;12:269–276.

3 Massin MM, Montesanti J, Gerard P, et al. Spectrum and frequency of illness presenting to a pediatric emergency department. Acta Clin Belg. 2006;61:161–165.

4 Armon K, Stephenson T, Gabriel V, et al. Determining the common medical presenting problems to an accident and emergency department. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:390–392.

5 Nelson DS, Walsh K, Fleisher GR. Spectrum and frequency of pediatric illness presenting to a general community hospital emergency department. Pediatrics. 1992;90:5–10.

6 Weissbluth M. Your fussy baby, how to sooth your newborn. New York: Random House; 2003.

7 Brazelton T. Crying in infancy. Pediatrics. 1962;29:579–588.

8 Wurmser H, Laubereau B, Herman M, et al. Excessive infant crying: often not confined to the first 3 months of age. Early Hum Dev. 2001;64:1–6.

9 Wessel M, Cobb J, Jackson E, et al. Paroxysmal fussing in infancy, sometimes called colic. Pediatrics. 1954;14:421–435.

10 Poole S. The infant with acute, unexplained, excessive crying. Pediatrics. 1991;88:450–455.

11 Freedman S, Al-Harthy N, Thull-Freedman J. The crying infant: diagnostic testing and frequency of serious underlying disease. Pediatrics. 2009;123:841–848.

12 Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. American Academy of Pediatrics. Shaken baby syndrome: rotational cranial injuries—technical report. Pediatrics. 2001;108:206–210.

13 Glass R, Lew J, Gangarosa R, et al. Estimates of morbidity and mortality rates for diarrheal diseases in American children. J Pediatr. 1991;118:S27–S33.

14 Godbole P, Stringer M. Bilious vomiting in the newborn: how often is it pathologic? J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:909–911.

15 Parashar U, Holman R, Cummings K. Trends in intussusception-associated hospitalizations and deaths among US infants. Pediatrics. 2000;106:1413–1421.

16 Bundy D, Byerley J, Liles E, et al. Does this child have appendicitis? JAMA. 2007;298:438–451.

17 Steiner M, Dewalt D, Byerley J. Is this child dehydrated? JAMA. 2004;291:2746–2754.

18 Vega R, Avner J. A prospective study of the usefulness of clinical and laboratory parameters for predicting percentage of dehydration in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1997;13:179–182.

19 Strouse P. Disorders of intestinal rotation and fixation (“malrotation”). Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:837–851.

20 Vasavada P. Ultrasound evaluation of acute abdominal emergencies in infants and children. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:445–456.

21 Kwok M, Kim M, Gorelick M. Evidence-based approach to the diagnosis of appendicitis in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:690–698.

22 Reeves J, Shannon M, Fleisher G. Ondansetron decreases vomiting associated with acute gastroenteritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2002;109:e62.

23 Ramsook C, Sahagun-Carreon I, Kozinetz C, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing oral ondansetron with placebo in children with vomiting from acute gastroenteritis. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:397–403.

24 Freedman S, Adler M, Seshadri R, et al. Oral ondansetron for gastroenteritis in a pediatric emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1698–1705.

25 Practice parameter: the management of acute gastroenteritis in young children. American Academy of Pediatrics, Provisional Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Acute Gastroenteritis. Pediatrics. 1996;97:424–435.

26 Fonseca B, Hodgate A, Craig J. Enteral vs. intravenous rehydration therapy for children with gastroenteritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:483–490.