CHAPTER 25 Ectopic pregnancy

Incidence

In England and Wales between 1966 and 1996, the incidence of ectopic pregnancy increased 3.1-fold from 30.2 to 94.8 per 100,000 women aged 15–44 years, and 3.8-fold from 3.25 to 12.4 per 1000 pregnancies (Rajkhowa et al 2000). In the UK, for the 2003–2005 triennium, there were 11.1 [95% confidence interval (CI) 10.9–11.1] ectopic gestations per 1000 pregnancies reported (Lewis 2007).

In the USA, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have the most comprehensive data available on ectopic pregnancy. Between 1970 and 1989, there was a 5-fold increase in the incidence of ectopic pregnancies, from 3.2 to 16 per 1000 reported pregnancies (Goldner et al 1993). Women between 35 and 44 years of age have the highest risk of developing an ectopic pregnancy (27 per 1000 reported pregnancies). Data from the same centre indicate that the risk of ectopic pregnancy in African women (21 per 1000) is 1.6 times greater than the risk amongst Whites (13 per 1000); this is related to the high incidence of PID and low socioeconomic status in certain populations.

Ectopic pregnancy is still a cause of significant morbidity and mortality. In the UK, the number of deaths from ectopic pregnancies has varied in the last decade: 12 (1994–1996), 13 (1997–1999), 11 (2000–2002) and 10 (2003–2005). The death rate for the 2003–2005 triennium was 0.35 (95% CI 0.19–0.64) per 100,000 estimated ectopic pregnancies. Seven of the 10 deaths due to ectopic pregnancies during this triennium were associated with failure to diagnose or substandard care (Lewis 2007). The risk of death is higher for racial and ethnic minorities, and teenagers have the highest mortality rates.

Aetiology and Risk Factors

All sexually active women are at risk of an ectopic pregnancy. The risk factors that may be associated with an ectopic pregnancy (Table 25.1) may be present in 25–50% of women.

Previous tubal surgery

Sterilization

Following sterilization, the absolute risk of ectopic pregnancy is reduced. However, the ratio of ectopic to intrauterine pregnancy is higher. The greatest risk for pregnancy, including ectopic pregnancy, occurs in the first 2 years after sterilization. The cumulative probability of ectopic pregnancy for all methods of tubal sterilization is 7.3 per 1000 procedures. Fistula formation and recanalization of the proximal and distal stumps of the fallopian tube are implicated for the occurrence of ectopic gestation. Women sterilized before the age of 30 years by bipolar tubal coagulation have a 27 times higher probability of ectopic pregnancy compared with postpartum partial salpingectomy (31.9 vs 1.2 ectopic pregnancies per 1000 procedures) (Peterson et al 1997). Tubal coagulation has a lower risk of pregnancy compared with mechanical devices (spring-loaded clips or fallope rings), but the risk of ectopic pregnancy is 10 times higher when a pregnancy does occur (DeStefano et al 1982).

Tubal reconstruction and repair

Reconstructive tubal surgery is a predisposing factor for ectopic pregnancy. However, it remains unclear whether the increased risk results from the surgical procedure or from the underlying pathology of the ciliated tubal epithelium and pelvic disease. In a consecutive series of 232 tubal microsurgical operations, including salpingostomies, proximal anastomoses and adhesiolyses, 12 patients (5%) presented with an ectopic pregnancy whereas 80 patients (35%) achieved an intrauterine pregnancy (Singhal et al 1991). Silva et al (1993) reported a higher risk of recurrent ectopic pregnancy following conservative surgery of salpingostomy than radical surgery of salpingectomy (18% vs 8%, relative risk 2.38, 95% CI 0.57–10.01).

Pelvic inflammatory disease

The relationship between PID, tubal obstruction and ectopic pregnancy is well documented. Infection of tubal endothelium results in damage of ciliated epithelium and formation of intraluminal adhesions and pockets. A consequence of these anatomical changes is entrapment of the zygote and ectopic implantation of the blastocyst. Westrom et al (1981) studied 450 women with laparoscopically proven PID (case–control study). The authors reported that the incidence of tubal obstruction increased with successive episodes of PID: 13% after one episode, 35% after two episodes and 79% after three episodes. Following one episode of laparoscopically verified acute salpingitis, the ratio of ectopic to intrauterine pregnancy was 1:24, a six-fold increase compared with women with laparoscopically negative results.

Current intrauterine contraceptive device users

Unmedicated, medicated and copper-coated IUCDs prevent both intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancies. However, a woman who conceives with an IUCD in situ is seven times more likely to have a tubal pregnancy compared with conception without contraception (Vessey et al 1974). IUCDs are more effective in preventing intrauterine than extrauterine implantation. With copper IUCDs, 4% of all accidental pregnancies are tubal, whereas with progesterone-coated IUCDs, 17% of all contraceptive failures are tubal pregnancies. The different mechanisms of action of the two devices could partially explain the difference in failure rates. Although both devices prevent implantation, copper IUCDs also interfere with fertilization by inducing cytotoxic and phagocytotic effects on the sperm and oocytes. Progesterone-containing IUCDs are probably less effective in preventing fertilization. Although the incidence of pregnancy diminishes with long-term use of the IUCD, among women who become pregnant, the likelihood of ectopic pregnancy increases. Women who have used the IUCD for more than 24 months are 2.6 times more likely to have an ectopic pregnancy compared with short-term users (<24 months). The ‘lasting effect’ of the IUCD may be related to the loss of the cilia from the tubal epithelium, especially if the IUCD has been in situ for 3 years or more (Wollen et al 1984, Ory HW 1981).

Termination of pregnancy

Data from two French case–control studies suggest that induced abortion may be a risk factor for ectopic pregnancy for women with no history of ectopic pregnancy. There is an association between the number of previous induced abortions and ectopic pregnancy [odds ratio (OR) 1.4 for one previous induced abortion and 1.9 for two or more] (Tharaux-Deneux et al 1998). Whether this is related to the spread of asymptomatic C. trachomatis infection or to the procedure itself is uncertain.

Assisted conception

Induction of ovulation with either clomiphene citrate or human menopausal gonadotrophin is a predisposing factor to tubal implantation (McBain et al 1980; Marchbanks et al 1985). A number of studies indicate that 1–4% of pregnancies achieved following induction of ovulation are ectopic pregnancies. The majority of these patients had a normal pelvis and patent tubes. The incidence of tubal pregnancy following oocyte retrieval and embryo transfer is approximately 4.5%. It must be noted that some women who undergo an in-vitro fertilization (IVF) cycle have risk factors for an ectopic pregnancy (i.e. previous ectopic pregnancy, tubal pathology or surgery).

Salpingitis isthmica nodosa

Salpingitis isthmica nodosa (SIN) is diagnosed by the histological evidence of tubal isthmic diverticula, and may be suggested by characteristic changes on hysterosalpingogram. Its incidence in healthy women ranges from 0.6% to 11%, but it is significantly more common in the setting of ectopic pregnancy. Persaud (1970) reported that 49% of fallopian tubes excised for tubal pregnancy had diverticula and evidence of SIN. The reason for the high incidence of ectopic gestation in women with SIN remains largely unknown. Defective myoelectrical activity has been demonstrated over the diverticula. Entrapment of the embryo into the diverticula is a possible mechanical explanation.

Smoking

A French study found that the risk of ectopic pregnancy is significantly higher in women who smoke. The risk increases according to the number of cigarettes per day (Bouyer et al 1998). The relative risk for ectopic pregnancy is 1.3 for women who smoke one to nine cigarettes per day, 2 for women who smoke 10–12 cigarettes per day, and 2.5 for women who smoke more than 20 cigarettes per day. Inhibition of oocyte cumulus complex pick-up by the fimbrial end of the fallopian tube and a reduction of ciliary beat frequency are associated with nicotine intake (Knoll and Talbot 1998).

Diethylstilboestrol

Results of a collaborative study indicate that the risk of ectopic pregnancy in diethylstilboestrol (DES)-exposed women was 13% compared with 4% for women who had a normal uterus (Barnes et al 1980). A meta-analysis on risk factors for ectopic pregnancy confirms that exposure to DES in utero significantly increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy (Ankum et al 1996).

Pathology

Sites of ectopic pregnancy

A 21-year survey of 654 ectopic pregnancies (Breen 1970) revealed that the most common sites of ectopic pregnancy are as shown in Table 25.2. Similar distribution for tubal and abdominal pregnancy sites have been reported by Bouyer et al (2002) [ampullary (70.0%), isthmic (12.0%), fimbrial (11.1%), interstitial (2.4%), abdominal (1.3%)]. In this population, no cervical pregnancies were observed and slightly increased incidence was seen for ovarian pregnancies (3.2%) (Bouyer et al 2002).

| Fallopian tube | |

| Ampullary segment | 80% |

| Isthmic segment | 12% |

| Fimbrial end | 5% |

| Interstitial and cornual | 2% |

| Abdominal | 1.4% |

| Ovarian | 0.2% |

| Cervical | 0.2% |

Natural progression of a tubal pregnancy

Time of rupture at various sites in the tube

Diagnosis

Symptoms and signs

Ectopic pregnancy remains a diagnostic challenge. It should be considered as an important differential in any woman of reproductive age who presents with the triad of amenorrhoea, abdominal pain and irregular vaginal bleeding. This philosophy is particularly useful if the patient has any of the risk factor(s) identified in Table 25.1. The frequency with which various symptoms and signs were reported from a series of 300 consecutive cases are shown in Table 25.3 (Droegemueller 1982).

Table 25.3 Symptoms and signs in 300 consecutive cases of ectopic pregnancy at admission

| Symptoms and signs | Cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | 99 |

| Generalized | 44 |

| Unilateral | 33 |

| Radiating to the shoulder | 22 |

| Abnormal uterine bleeding | 74 |

| Amenorrhoea ≤2 weeks | 68 |

| Syncopal symptoms | 37 |

| Adenexal tenderness | 96 |

| Unilateral adenexal mass | 54 |

| Uterus | |

| Normal size | 71 |

| 6–8-week size | 26 |

| 9–12-week size | 3 |

| Uterine cast passed away vaginally | 7 |

| Admission temperature >37°C | 2 |

Amenorrhoea and abnormal uterine bleeding

Most patients present with amenorrhoea of at least 2 weeks duration. One-third of the women will either not recall the date of their last menstrual period or have irregular periods. Abnormal uterine bleeding occurs in 75% of women with an ectopic pregnancy. The bleeding is often light, recurrent and results from detachment of the uterine decidua. According to Stabile (1996a), ‘If a patient who is a few weeks pregnant complains of a little pain and heavy vaginal bleeding, the pregnancy is probably intrauterine, whereas if there is more pain and little bleeding, it is more likely to be an ectopic pregnancy’.

Other symptoms

Although abdominal pain, amenorrhoea and abnormal vaginal bleeding are the most common and typical symptoms, patients may present with additional features such as syncopal attacks. These are related to sudden-onset haemorrhage or to hypovolaemia or anaemia. Other atypical symptoms include diarrhoea or vomiting. In the 2003–2005 Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health report (Lewis, 2007), some women who presented with these symptoms were undiagnosed and subsequently died.

Types of presentation

The presentation of symptomatic patients with a tubal ectopic pregnancy may be acute or subacute.

Acute presentation

This is usually a consequence of rupture of the ectopic gestation and the ensuing intraperitoneal haemorrhage and haemodynamic shock. These symptoms are due to the intra-abdominal haemorrhage and collection of blood into the subdiaphragmatic region and pouch of Douglas. The patient is often pale, hypotensive and tachycardic. She may complain of shoulder tip pain or urge to defaecate. Abdominal examination reveals generalized and rebound tenderness. Vaginal examination will reveal tenderness in the adnexal region and cervical motion tenderness. However, vaginal examination in patients who present with an acute abdomen due to a ruptured ectopic pregnancy is generally considered unnecessary and potentially dangerous for the following reasons: (a) generalized haemoperitoneum and pain often mean that specific information cannot be elicited, (b) the patient is very uncomfortable and the assessment is often difficult and inadequate, and (c) it could result in total rupture of the ectopic pregnancy and delay management of the patient. Although it is reported that 30% of all women with an ectopic pregnancy present after rupture (Barnhart et al 1994), acute presentation is becoming less common. This is due primarily to increased patient awareness and early referral to the hospital for evaluation of ‘suspected ectopic’ pregnancies. Finally, the availability of more sensitive and rapid biochemical tests for beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin (β-hCG) quantification and the wider availability of transvaginal ultrasonography and laparoscopy have significantly reduced the interval between presentation and treatment.

Subacute presentation

When the process of tubal rupture or abortion is very gradual, the presentation of ectopic pregnancy is subacute. According to Stabile (1996a,b), this is the group of women who are symptomatic but clinically stable. A history of a missed period and recurrent episodes of light vaginal bleeding may exist. The circulatory system adjusts the blood pressure, and the patient is haemodynamically stable. Progressively increasing lower abdominal pain and, occasionally, shoulder pain are typical symptoms. On bimanual examination, there may be localized tenderness in one of the fornices, and cervical motion tenderness is often present. Subacute presentation occurs in 80–90% of ectopic pregnancies. In cases with such a presentation, the establishment of an accurate diagnosis becomes more difficult, hence the need for further investigations.

Further Investigations

Biochemical tests

Serial β-hCG measurements

Serum β-hCG concentrations double every 1.4–1.6 days from the time of first detection up to the 35th day of pregnancy, and then double every 2.0–2.7 days from the 35th to the 42nd day of pregnancy (Pittaway et al 1985). Since the normal doubling time of β-hCG is 2.2 days and its half-life is 32–37 h, serial quantitative assessments of β-hCG may help to distinguish normal from abnormal pregnancies. Kadar et al (1981) first reported a method for screening for ectopic pregnancy based on β-hCG doubling time. An increase in serum β-hCG of less than 66% over 48 h was suggestive of an ectopic pregnancy (using an 85% CI for β-hCG levels). More recently, studies have used an increase in serum β-hCG levels of 35–53% (using 99% CI) to diagnose viable intrauterine pregnancies and to reduce the potential risk of terminating an intrauterine pregnancy (Seeber et al 2006). However, another method used to help with the diagnosis of an ectopic pregnancy is the ‘plateau’ in serum β-hCG levels. Plateau is defined as a β-hCG doubling time of 7 days or more (Kadar and Romero 1988). If the half-life of serum β-hCG is less than 1.4 days, spontaneous miscarriage is likely, whereas a half-life of more than 7 days is more likely to be indicative of an ectopic pregnancy. Therefore, falling levels of β-hCG can distinguish between an ectopic pregnancy and a spontaneous miscarriage. As a proportion of ectopic pregnancies are tubal miscarriages (with biochemical changes similar to those of intrauterine miscarriages), and approximately 15–20% of all ectopic pregnancies can have doubling serum β-hCG levels similar to those of normal intrauterine pregnancies (Silva et al 2006), suboptimal serial β-hCG changes are not specific or sensitive enough to diagnose ectopic pregnancies.

Serum progesterone

Progesterone concentrations have been widely used for the diagnosis and management of pregnancies of unknown location (PUL, i.e where ultrasound is inconclusive). In failing pregnancies, whether ectopic or miscarriage, progesterone concentrations are expected to be low compared with values in healthy ongoing pregnancies (Hahlin et al 1990). Most studies report cut-off concentrations of less than 16 nmol/l for failing pregnancies and more than 80 nmol/l for healthy ongoing pregnancies (Mathews et al 1986, Sau and Hamilton-Fairley 2003, Bishry and Ganta 2008). Progesterone levels over 25 nmol/l are ‘likely to indicate’ and levels over 60 nmol/l are ‘strongly associated with’ pregnancies subsequently shown to be normal. A progesterone concentration below 25 nmol/l in an anembryonic pregnancy has been shown to be diagnostic of non-viability (Elson et al 2003). Concentrations less than 20 nmol/l have a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 94% for the prediction of spontaneous resolution of PULs (Banerjee et al 2001). A meta-analysis has demonstrated that a single serum progesterone measurement is good at predicting a viable intrauterine or failed pregnancy, but is not useful for locating the site of pregnancy (Mol et al 1998). When interpreting progesterone measurements, variations in concentrations should be taken into account because of the assay methods, and a departmental protocol should state the normal range for that unit.

Ultrasonography

A review of the literature by Brown and Doubilet (1994) revealed the frequency of various ultrasound features in ectopic pregnancies as detailed below:

In ectopic pregnancies, a hyperechogenic tubal ring (’doughnut’ or ‘bagel’ sign) is the most common finding on ultrasound scan. Others include a mixed adnexal mass representing either tubal miscarriage or tubal rupture, an ectopic sac with a yolk sac, or an embryo with or without a fetal heartbeat. The corpus luteum may be present on the ipsilateral side in 85% of cases. It has been reported that 74% of ectopic pregnancies can be visualized on initial transvaginal ultrasound scan, and more than 90% of ectopic pregnancies can be visualized prior to treatment (Kirk et al 2007).

Quantitative assessment of β-hCG levels is essential for the accurate interpretation of ultrasonographic findings. A single serum β-hCG measurement has been used as a discriminatory level to help with the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Absence of an intrauterine gestational sac with serum β-hCG levels of 6500 IU/l or more has an 86% positive predictive value and a 100% negative predictive value for the presence of an ectopic pregnancy (Romero et al 1985). With transvaginal ultrasound scan, different discriminatory levels of serum β-hCG (e.g. 1000, 1500 and 2000 IU/l) have been used with no significant difference in the detection rates of ectopic pregnancies (Barnhart et al 1999, Condous et al 2005). Failure to visualize an intrauterine gestational sac by transvaginal ultrasound if β-hCG concentrations are 1000–2000 IU/l or more indicates either an abnormal intrauterine pregnancy, a recent miscarriage or an ectopic pregnancy. It must be emphasized that although the discriminatory zone for an intrauterine pregnancy is well established, there is no such discriminatory zone for ectopic pregnancies. In 15–20% of women with clinical suspicion of an early pregnancy failure, ultrasound findings are not diagnostic.

Doppler ultrasonography

Jurkovic et al (1992), in a prospective study, used colour Doppler to detect and compare changes of blood flow in the uterine and spiral arteries and the corpus luteum in ectopic and intrauterine pregnancies. In intrauterine pregnancies, the impedance to flow (resistance index) in uterine arteries decreased with gestational age, but this remained constant in ectopic pregnancies. Peak blood velocity in the uterine arteries increased with gestational age in intrauterine pregnancies, and the values were significantly higher than those seen in ectopic pregnancies. However, uterine blood flow velocity was lower in the ectopic group, indicating an overall reduction in uterine blood supply. Local vascular changes associated with a true gestational sac differentiate an intrauterine pregnancy from the pseudo sac of an ectopic pregnancy. Doppler flow imaging may thus suggest that an adnexal mass is an ectopic pregnancy from the presence of high vascularity at the periphery of the adnexal mass.

Three-dimensional ultrasonography

Three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound is emerging as a possible additional diagnostic tool for ectopic pregnancy. Rempen (1998) conducted a prospective follow-up study in order to evaluate the potential of 3D ultrasound to differentiate intrauterine gestations from extrauterine gestations. Fifty-four pregnancies with a gestational age of less than 10 weeks and with an intrauterine gestational sac more than 5 mm in diameter were included in the study. The configuration of the endometrium in the frontal plane of the uterus was correlated with pregnancy outcomes. It was found that this configuration was asymmetrical in 84% of intrauterine pregnancies, whereas the endometrium showed asymmetry in 90% of extrauterine pregnancies (P ≤ 0.0001). The conclusion was that evaluation of the endometrial shape in the frontal plane may be a useful additional means of distinguishing intrauterine from extrauterine pregnancies.

Harika et al (1995) conducted a study to assess the role of 3D imaging in the early diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy on 12 asymptomatic patients whose gestational age was less than 6 weeks. Nine of these patients had an ectopic pregnancy at laparoscopy, and of these, 3D transvaginal ultrasound showed a small ectopic gestational sac in four cases. These preliminary results suggest that 3D ultrasound may be an effective procedure for the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy in asymptomatic patients prior to the sixth gestational week; however, its accuracy would have to be refined.

Pregnancy of Unknown Location

In recent years, PUL has been used as a diagnosis for patients with a positive pregnancy test with no signs of intrauterine or extrauterine pregnancy or retained products of conception on an initial transvaginal ultrasound scan. Studies report that PUL is identified in 8–31% of women referred for ultrasound assessment in early pregnancy (Hahlin et al 1995, Condous et al 2004).

PULs present a management dilemma for health professionals in the early pregnancy unit, and inevitably increase workload and time consumption. For clinically stable women, expectant management has been demonstrated to be safe. PULs are followed up with serial hormone measurements, repeat transvaginal ultrasound scans and possibly laparoscopy with or without uterine curettage. It is important to note that in women with a history and transvaginal ultrasound findings suggestive of complete miscarriage, serial β-hCG measurements should be performed as approximately 6% of these can be ectopic pregnancies (Condous et al 2004b).

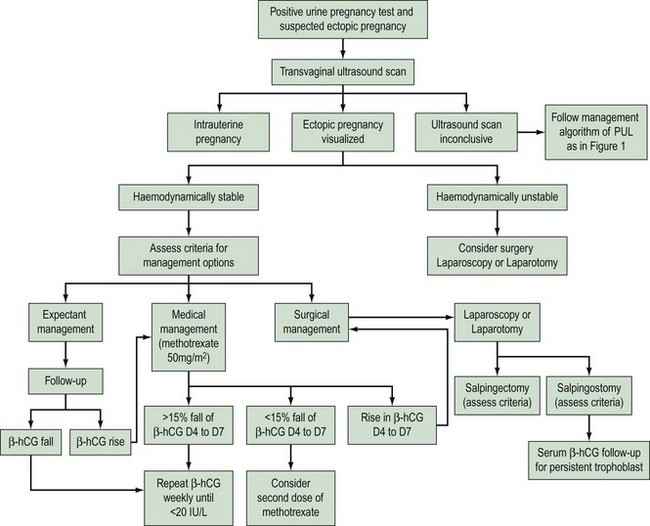

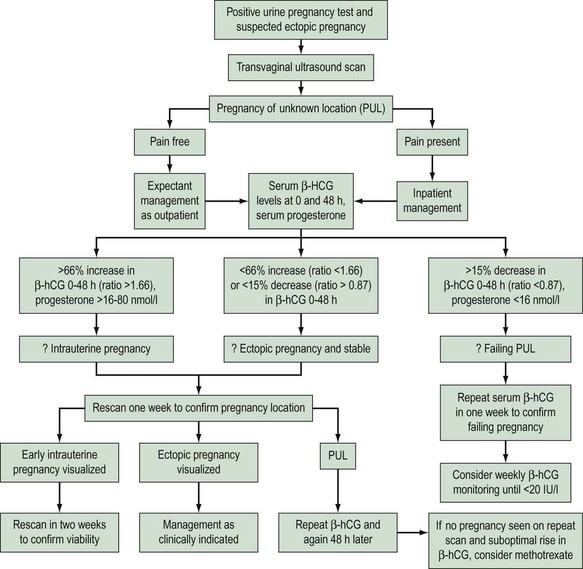

Recently, the use of β-hCG ratios (β-hCG 48 h/β-hCG 0 h) rather than absolute β-hCG values has been assessed in the diagnosis and management of PUL. A β-hCG ratio below 0.87 (or a β-hCG decrease >13%) has a 92.7% sensitivity (95% CI 85.6–96.5) and a 96.7% specificity (95% CI 90.0–99.1) for the prediction of a failing pregnancy (Condous et al 2006, Bignardi et al 2008). Various mathematical models using log regression and the Bayesian approach have been developed to predict the outcome of PULs; however (Condous et al 2004), these need to be tested prospectively in multicentre trials. Figure 25.1 shows an algorithm for the management of women with PUL.

Management of Ectopic Pregnancy

Figure 25.2 shows a summary of the algorithm for managing ectopic pregnancies. The following section should be read in tandem with this figure.

Surgical treatment

Laparoscopy or laparotomy

A systematic review has shown that laparoscopic salpingostomy is significantly less successful than the open surgical approach in the elimination of tubal ectopic pregnancy (two randomized controlled trials, n = 165, OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.09–0.86) due to a significantly higher persistent trophoblast rate in laparoscopic surgery (OR 3.5, 95% CI 1.1–11). However, the laparoscopic approach is significantly less costly than open surgery. Long-term follow-up (n = 127) shows no evidence of a difference in intrauterine pregnancy rate, but there is a non-significant tendency to a lower repeat ectopic pregnancy rate (Hajenius et al 2007). The laparoscopic approach is associated with less intraoperative blood loss, lower analgesic requirements and a shorter duration of hospitalization and convalescence. An additional benefit of the laparoscopic approach is significantly fewer adhesions at the surgical site compared with those treated by laparotomy (Lundorff et al 1991).

Salpingectomy

When to consider salpingectomy

Salpingectomy is indicated for women with:

No randomized controlled trials have compared salpingectomy and salpingotomy. Results from four cohort studies suggest that there may be a higher subsequent intrauterine pregnancy rate associated with salpingotomy, but the magnitude of this benefit may be small (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2004). The possibility of further ectopic pregnancies in the conserved tube should also be discussed if salpingotomy is being considered. In the presence of a healthy contralateral tube, there is no clear evidence that salpingotomy should be used in preference to salpingectomy.

Linear salpingotomy

An incision is made on the antimesenteric border of the fallopian tube with either a needle-point monopolar cutting diathermy, scalpel, scissors or laser, and the tubal lumen is exposed. The products of conception are removed with grasping forceps. Sometimes the laparoscopic suction/irrigation probe may be used for aqua dissection and removal of the products of conception by suction. Irrigation of the tubal lumen after removal of the products of conception is essential. Thereafter, haemostasis is achieved with electrocoagulation. The incision can either be closed with a fine non-absorbable suture material such as 6/0 Prolene, or left open (salpingotomy) for healing to occur by secondary intention. Either approach results in satisfactory healing of the tubal wall. A study by Tulandi and Guralnick (1991) showed that there was no significant difference in the number of subsequent intrauterine pregnancies, number of ectopic pregnancies or incidence of adhesion formation with either method.

The use of conservative surgery exposes the women to a small risk of tubal bleeding in the immediate postoperative period, persistent trophoblast and the risk of subsequent ectopic pregnancy in the conserved tube. For identification and treatment of persistent trophoblast, these women should be followed by serial β-hCG measurements post surgery. Treatment with methotrexate can be initiated if β-hCG concentrations fail to fall as expected. Sauer et al (1997) initiated treatment if serum β-hCG was more than 10% of the preoperative level by 10 days after surgery, and Pouly et al (1991) initiated treatment if serum β-hCG was more than 65% of the initial level at 48 h post surgery. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to recommend ideal cut-off concentrations of serum β-hCG for commencing treatment, but protocols for identification and treatment of persistent trophoblast should be present in every unit.

Fimbrial evacuation

Fimbrial evacuation is indicated when the pregnancy lies in the fimbrial segment of the fallopian tube. It involves gentle and progressive compression of the tube, starting just proximal to the side of the pregnancy and moving it systematically to the fimbrial end of the tube. When the pregnancy is located at the ampullary part, fimbrial evacuation or ‘milking of the tube’ is not recommended. The external pressure required to propel the ectopic pregnancy and achieve a tubal miscarriage is likely to cause severe damage to the endosalpinx and excessive bleeding from the implantation site, and the procedure is associated with a greater risk of persistent trophoblastic disease (Brosens et al 1984). When milking was compared with linear salpingotomy for ampullary ectopic pregnancy, milking was associated with a two-fold increase in the recurrent ectopic pregnancy rate (Smith et al 1987).

Reproductive outcome

In patients who underwent radical surgery (salpingectomy), the subsequent intrauterine pregnancy rate was 49.3% (range 36.6–71.4%) and the recurrent ectopic pregnancy rate was 10% (range 5.8–12%). In patients who underwent conservative surgery, the subsequent intrauterine pregnancy rate was 53% (range 38–83%) and the recurrent ectopic pregnancy rate was 14% (range 6.4–21.2%). These results are based on a retrospective analysis of nine studies in a total of 2635 patients, and indicate that conservative surgery is associated with higher subsequent intrauterine pregnancy and higher recurrent ectopic rates compared with radical surgery (Yao and Tulandi 1997). However, the variations in the design of each study make strict comparison of the results very difficult. Similar figures of intrauterine pregnancy (83.7%) and recurrent ectopic pregnancy (8%) have been reported when expectant management is compared with salpingectomy (Helmy et al 2007).

Medical treatment with methotrexate

Early detection of an ectopic pregnancy, the desire to retain fertility, and minimizing costs and surgical morbidity are the main reasons for incorporating medical treatment as an option for managing ectopic pregnancies. The most frequently used drug is methotrexate and this will therefore be discussed in detail, although other agents have been used. Gynaecologists are familiar with methotrexate because the drug has been used very effectively for the treament of gestational trophoblastic disease since 1955 (Li et al 1956). Hreschchyshyn et al (1965) were the first to report on the use of methotrexate in the management of ectopic pregnancy. In 1982, Tanaka et al reported on the treatment of an unruptured interstitial pregnancy with a course of intramuscular methotrexate.

Who will benefit from methotrexate?

Contraindications

Although medical management can be successful at serum β-hCG concentrations greater than 3000 IU/l, quality-of-life data suggest that methotrexate should only be used with serum β-hCG concentrations below 3000 IU/l. Shalev et al (1995) reported that following intratubal administration of methotrexate, the failure rate was 24% when the tubal diameter was less than 2 cm and 48% when the diameter was more than 2 cm. The authors recommend that methotrexate should only be used when the size of the ectopic pregnancy is less than 2 cm. Stovall and Ling (1993) found that the administration of methotrexate to patients who had a fetal heartbeat on ultrasound scan was associated with a 14.3% failure rate. In the group of patients without fetal cardiac activity, the failure rate was 4.7%.

Routes of administration and dose

Methotrexate can be administered systemically (intravenously or intramuscularly) or locally using a laparoscopic or transvaginal ultrasound-guided approach. The transvaginal administration of methotrexate under sonographic guidance requires visualization of an ectopic gestational sac, and specific skills and expertise of the clinician. This mode of administration is less invasive and more effective than the laparoscopically ‘blind’ intratubal injection. Two randomized controlled trials (Fernandez et al 1994, Cohen et al 1996) suggested that local injection of methotrexate was equivalent in effect to systemic methotrexate. The major advantages of direct injection of methotrexate into the tube include smaller dose of the drug, higher tissue concentration and fewer systemic side-effects. In comparison, systemic methotrexate is practical, easier to administer and less dependent on clinical skills. The published literature includes a wide spectrum of protocols for the systemic administration of methotrexate, including:

The success rate of all three regimens is comparable. Three trials have shown that the administration of methotrexate in a single IM dose of 50 mg/m2 body surface area is associated with a complete reabsorption rate of 92%, a subsequent intrauterine pregnancy rate of 58% and a recurrent ectopic pregnancy rate of 9% (Hajenius et al 2007). Reabsorption rate is defined as the time interval between initiation of therapy and undetectable serum hCG concentration. The mean reabsorption time is 30 days, ranging from 5 to 100 days. Tubal patency is reported to be 50–100% (mean 71%) after systemic administration of methotrexate.

Laparoscopic surgery vs methotrexate

O’Shea et al (1994) published the results of a prospective randomized trial comparing intra-amniotic methotrexate with carbon dioxide laser laparoscopic salpingotomy. The salpingotomy group and the local methotrexate group had comparable success rates: 87.5% and 89.7%, respectively. A systematic review showed that systemic methotrexate in a fixed multiple dose IM regimen has a non-significant tendency to higher treatment success than laparoscopic salpingostomy (OR 1.8, 95% CI 0.73–4.6). No significant differences are found in long-term follow-up for intrauterine pregnancy and repeat ectopic pregnancy (Hajenius et al 2007). Methotrexate appears to be effective in a selective group of patients with ectopic pregnancy. Direct and indirect costs of medical therapy are less than half of those associated with laparoscopy. Intramuscular administration eliminates anaesthetic and surgical risks arising from laparoscopic injection of the drug. However, the long-term effect of locally injected pharmacological substances upon the endosalpinx remains largely unknown.

Serum β-hCG levels should be checked 4 and 7 days after the first dose of methotrexate, and a further dose is given if β-hCG levels have failed to fall by more than 15% between days 4 and 7. The level of serum β-hCG is likely to increase between days 1 and 4 after treatment. It has been suggested that although methotrexate is arresting mitosis in the cytotrophoblast, the syncytiotrophoblast may still be able to produce β-hCG. Also, destruction of the cells releases more β-hCG into the systemic circulation. Approximately 15% of women require more than a single dose of methotrexate, and 7% experience tubal rupture during follow-up (Yao and Tulandi 1997, Sowter et al 2001).

It is important to recognize that abdominal pain occurs in 30–50% of patients 6–7 days after the administration of methotrexate. The gynaecologist has to decide if the pain is due to imminent tubal rupture, existing tubal rupture or simply represents postmethotrexate pain. Postmethotrexate pain is localized in the lower abdomen. Its precise aetiology remains largely unknown, but it is likely to be due to a combination of factors, including destruction of the trophoblastic tissue and transtubal haemorrhage leading to peritoneal irritation. Close monitoring of patients is essential in order to avoid unnecessary surgical intervention in the form of laparoscopy or laparotomy. According to Stovall (1995), regular assessment of haemoglobin is the most useful parameter. The pain usually subsides within 24–48 h and occasionally precedes or follows an episode of vaginal bleeding.

Brown et al (1991) assessed the clinical value of serial transvaginal ultrasonography in the monitoring of ectopic pregnancies treated with methotrexate, and concluded that routine ultrasonography is not necessary after methotrexate treatment. There was no correlation between the pattern of resolution of β-hCG levels and sonographic findings.

Mifepristone and methotrexate

Mifepristone (RU486) has been used in combination with methotrexate for the medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy (Gazvani and Emery 1999). A non-randomized study from France (Perdu et al 1998) only reported one failure in the 30 patients treated with IM methotrexate and oral mifepristone, and 11 failures in 42 patients treated with methotrexate alone. The authors concluded that the combination of mifepristone and methotrexate decreased the risk of failure in medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy. However, further prospective randomized studies are needed to evaluate the role of mifepristone in the medical management of ectopic pregnancy.

Controlled expectant management

Ten prospective studies, with a total of 347 patients managed expectantly, demonstrated that 69% of the ectopic gestations resolved spontaneously. All patients were haemodynamically stable and had decreasing serum β-hCG levels. However, other variables such as size and location of the ectopic pregnancy or presence of fetal cardiac activity were not always specified (Yao and Tulandi 1997). Interventions are required in approximately 23–29% of cases with expectant management (Hahlin et al 1995).

The essential prerequisite for successful expectant management of ectopic gestation is appropriate selection of patients. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2004) issued guidelines for the management of tubal pregnancy. The conclusion was that expectant management is more likely to be successful in the following circumstances:

Non-Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy

Cervical pregnancy

A cervical pregnancy is one that implants entirely within the cervical canal. The reported incidence ranges from one in 2500 to one in 18,000 deliveries (0.2% of ectopic pregnancies). Predisposing factors for the development of cervical pregnancy include previous instrumentation of the endocervical canal, previous caesarean delivery, Asherman’s syndrome and exposure to DES. Sporadic cases of cervical pregnancy have been reported after controlled ovarian stimulation with human menopausal gonadotrophins and intrauterine insemination, as well as IVF (Weyerman et al 1989).

Cervical pregnancy produces profuse vaginal bleeding without associated cramping pain. In some cases of advanced pregnancies, it can be associated with urinary symptoms. The clinical and ultrasound criteria for the diagnosis of cervical pregnancy are summarized below (Hofmann et al 1987).

Ultrasound criteria

Early forms of cervical pregnancy are managed conservatively. Conservative treatment includes the use of systemic methotrexate, intra-amniotic feticide, reduction of blood supply and tamponade. Transvaginal ultrasound-guided local injection of the ectopic pregnancy with methotrexate or potassium chloride has been shown to be successful (Benson and Doubilet 1996). This technique has been used for the treatment of heterotopic coexistent cervical and intrauterine pregnancy. Similarly, systemic methotrexate alone is 91% efficacious in the treatment of cervical ectopic pregnancy, and a combination of intra-amniotic and systemic methotrexate therapy has been used to increase the chance of successful treatment (Kung and Chang 1999). Currently, there is no recommendation for the optimal dose and route of administration of methotrexate for the treatment of cervical ectopic pregnancy, although gestational age less than 9 weeks, serum β-hCG below 10,000 IU/l, absent fetal cardiac activity and crown–rump length less than 10 mm are associated with a greater chance of success with conservative treatment (Hung et al 1998).

Removal of the products of conception from the cervical canal by suction curettage is likely to stop the haemorrhage. Conservative measures used to arrest bleeding include packing of the uterus and cervix, and insertion of an intracervical 30-ml Foley catheter to arrest bleeding, insertion of sutures to ligate the lateral cervical vessels or placement of a cervical cerclage (Kirk et al 2006). In some cases, because of the depth of trophoblastic invasion, major blood vessels are involved and more radical measures such as bilateral uterine artery or internal iliac artery ligation are necessary to control the bleeding. When all the conservative measures have failed to arrest the bleeding, hysterectomy is required. Preoperatively, the patient must be informed about the possibility of hysterectomy and sign the appropriate consent.

Caesarean scar ectopic pregnancy

This is a relatively recent description for ectopic pregnancy location. The incidence is not well known as there are only a few case reports of first trimester caesarean scar ectopic pregnancies described in the literature. Risk factors include previous caesarean section, myomectomy, adenomyosis, IVF, previous dilatation and curettage, and manual removal of the placenta. Clinical presentation can be with either hypovolaemic shock and uterine rupture or painless vaginal bleeding. Ultrasound diagnostic criteria as described by Jurkovic et al (2003) include an empty uterine cavity, a gestational sac located anteriorly at the level of the internal cervical os covering the visible or presumed site of previous lower segment caesarean scar, evidence of functional trophoblastic circulation on Doppler examination, and a negative ‘sliding organs sign’. In some cases, hysteroscopy and magnetic resonance imaging have also been used to aid in the diagnosis.

Medical, expectant and surgical methods of management have all been reported. Expectant management does not seem to be an appropriate choice as there is a greater risk of scar rupture and subsequent emergency hysterectomy. As a primary treatment, transvaginal ultrasound-guided local injection of methotrexate (25 mg) in the ectopic gestation has been shown to be associated with a 70–80% success rate (Jurkovic et al 2003). In the presence of fetal cardiac activity, potassium chloride in the ectopic sac followed by local methotrexate has also been shown to be effective (Jurkovic et al 2003). Lastly, there are reports on successful outcome with the use of systemic methotrexate followed by suction evacuation (Marchiolé et al 2004, Graesslin et al 2005).

Surgical management with suction curettage under ultrasound guidance followed by balloon tamponade is successful in reducing heavy intraoperative bleeding. Uterine artery embolization can also be used as an adjunctive therapy to reduce bleeding. An alternative approach can be the use of a Shirodkar suture prior to suction evacuation, with approximately 79% of cases requiring the suture to be tied to reduce bleeding (Jurkovic et al 2007). Finally, in cases presenting with hypovolaemic shock, laparotomy followed by hysterectomy is the only option available.

Ovarian pregnancy

Ovarian pregnancy represents the most common type of non-tubal ectopic pregnancy and occurs in 0.2–1% of all ectopic pregnancies. The incidence ranges from one in 40,000 to one in 7000 deliveries. Ovarian pregnancy has been reported after IVF treatment (Marcus and Brinsden 1993) and clomifene citrate ovulation induction (De Muylder et al 1994). The only risk factor associated with the development of an ovarian pregnancy is the current use of an IUCD.

The symptoms and signs of an ovarian pregnancy are similar to those of tubal pregnancy. Usually, the diagnosis is made during a laparoscopy or laparotomy. The classic criteria of Spiegelberg (1878) for the diagnosis of an ovarian pregnancy are as follows:

Transvaginal ultrasound can help in the diagnosis of an ovarian pregnancy which usually appears on or within the ovary as a cyst with a wide outer echogenic ring. A yolk sac or an embryo is rarely seen and the appearances usually lag in comparison with the gestational age (Comstock et al 2005). These are usually mistaken for corpus luteal cysts. 3D-ultrasound imaging has been shown to be useful in differentiating a corpus luteum from an ovarian pregnancy (Ghi et al 2007), whereas Doppler ultrasound is not very helpful in differentiating between them. Differential diagnoses include tubal pregnancy or complications of an ovarian cyst.

Abdominal pregnancy

There are two types of abdominal pregnancy:

Secondary abdominal pregnancies are far more common. Abdominal pregnancy represents approximately 1.4% of all ectopic pregnancies, and its incidence varies from one in 3000 to one in 10,000 deliveries. Abdominal pregnancies are associated with high maternal (0.5–1.8%) and perinatal mortality (40–95%) (Atrash et al 1987). The incidence of congenital fetal abnormalities ranges from 35% to 75%. Most of the abnormalities are caused by growth restriction and external pressure on the fetus. Common fetal problems include pulmonary hypoplasia, facial asymmetry and talipes.

The classic criteria for the diagnosis of primary abdominal pregnancy are:

The treatment is laparotomy as soon as the diagnosis is made. This is not to be undertaken lightly. The objectives are to remove the fetus and to ligate the umbilical cord close to the placenta without disturbing it. The placenta is allowed to be absorbed; if left alone, it rarely presents problems of bleeding or infection. The placenta should only be removed when the surgeon is absolutely certain that total haemostasis can be achieved. Removal of the placenta is possible if it is attached to the ovary, the broad ligament and the posterior surface of the uterus. Attempts to remove the placenta from other intra-abdominal organs are likely to cause massive haemorrhage due to the invasive properties of the trophoblast and the lack of cleavage planes. Adjuvant treatment with methotrexate along with selective arterial embolization has been recommended to stem the haemorrhage (Oki et al 2008). Placental involution can be monitored using serial ultrasonography and β-hCG concentrations. Potential complications of leaving the placenta in place include bowel obstruction, fistula formation, haemorrhage and peritonitis. The literature reports on successful management of abdominal pregnancies laparoscopically and with systemic methotrexate (Shaw et al 2007).

Interstitial pregnancy

The implantation site may be in the utero interstitial (inner segment), the true interstitial (middle segment) or the tubo interstitial (outer segment) region. The duration of pregnancy depends on its location. Implantation in either the inner or outer segments results in early rupture. Implantation in the middle segment involves a greater mass of myometrium and permits the pregnancy to advance to a somewhat later date. Rupture of the uterine wall is the most frequent outcome and the haemorrhage is usually severe. The signs and symptoms are similar to those of tubal ectopic pregnancy. Intermittent recurrent, sharp abdominal pain occurs at 4–6 weeks. Sudden severe abdominal pain is followed by collapse. Ultrasound diagnosis is made by visualization of the interstitial line adjoining the gestational sac and the lateral aspect of the uterine cavity, and continuation of the myometrial mantle around the ectopic sac (Jurkovic and Mavrelos 2007). Interstitial pregnancy must be differentiated from cornual myoma, pregnancy in one horn of a bicornuate uterus and a large endometrioma at the uterotubal junction.

Laparoscopy will reveal an asymmetrical enlargement of the uterus, displacement of the uterine fundus to the opposite side, elevation of the involved cornu, and rotation of the uterus on its long axis. The round ligament may be lateral to the gestational sac. Traditionally, interstitial pregnancies have been managed by laparotomy followed by wedge resection or hysterectomy. Since the 1990s, laparoscopic cornual resection and salpingotomy have become the surgical treatment of choice (Tulandi et al 1995). Laparoscopic vasopressin injection followed by excision of the pregnancy and endoloop closure or laparoscopic suturing for haemostasis has also been described.

Cornual pregnancy

The term ‘cornual pregnancy’ indicates that the pregnancy has occurred in one horn of a bicornuate uterus or in the rudimentary horn of a unicornuate uterus. It is very rare (one in 100,000 pregnancies) but carries a 5% maternal mortality. Asymmetrical enlargement of the early pregnant uterus should suggest a uterine anomaly. Unusual discomfort and tenderness may be described. Ultrasound criteria for diagnosis include a single interstitial part of the fallopian tube in the main uterine body, a gestational sac which is mobile and separate from the uterus, surrounded by myometrium and a vascular pedicle adjoining the gestational sac to the unicornuate uterus (Jurkovic and Mavrelos 2007).

Heterotopic pregnancy

Heterotopic pregnancy is defined as the simultaneous occurrence of an intrauterine and an extrauterine pregnancy. In spontaneous conception, the incidence has traditionally been quoted as one in 30,000 pregnancies. However, the incidence has risen to one in 3889 pregnancies due to the increased incidence of genital infections and the use of ovulation induction agents. With assisted conception techniques, particularly IVF and embryo transfer, 1–3% of all clinical pregnancies are heterotopic; therefore, it is imperative to visualize adnexae at the time of ultrasound scan for fetal viability (Svare et al 1993).

KEY POINTS

Ankum WM, Mol BW, van der Veen F, Bossuyt PM. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Fertility and Sterility. 1996;65:1093-1099.

Atrash HK, Frieda A, Hogue CJ. Abdominal pregnancy in the United States: frequency and maternal mortality. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1987;69:333-337.

Banerjee S, Aslam N, Woelfer B, Lawrence A, Elson J, Jurkovic D. Expectant management of early pregnancies of unknown location: a prospective evaluation of methods to predict spontaneous resolution of pregnancy. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2001;108:158-163.

Barnes AB, Colton T, Gundersen J, et al. Fertility and outcome of pregnancy in women exposed in utero to diethylstibestrol. New England Journal of Medicine. 1980;302:609-613.

Barnhart K, Mennuti MT, Benjamin I, Jacobson S, Goodman D, Coutifaris C. Prompt diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy in an emergency department setting. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;84:1010-1015.

Barnhart KT, Simhan H, Kamelle SA. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound above and below the beta-hCG discriminatory zone. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;94:583-587.

Barnhart KT, Sammel MD, Rinaudo PF, Zhou L, Hummel AC, Guo W. Symtomatic patients with early viable intrauterine pregnancy: HCG curves redefined. Obstetrics Gynecology. 2004;104:50-55.

Benson CB, Doubilet PM. Strategies for conservative treatment of cervical ectopic pregnancy. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;8:371-372.

Bignardi T, Condous G, Alhamdan D, et al. The hCG ratio can predict the ultimate viability of the intrauterine pregnancies of uncertain viability in the pregnancy of unknown location population. Human Reproduction. 2008;23:1964-1967.

Bishry E, Ganta S. The role of single serum progesterone measurement in conjunction with beta hCG in the management of suspected ectopic pregnancy. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2008;28:413-417.

Bouyer J, Coste J, Fernandez H, et al. Tobacco and ectopic pregnancy. Arguments in favour of a causal relation. Revue de Epidemologie et de Sante Publique. 1998;46:93-99.

Bouyer J, Coste J, Fernandez H, Pouly JL, Job-Spira N. Sites of ectopic pregnancy: a 10 year population-based study of 1800 cases. Human Reproduction. 2002;17:3224-3230.

Breen JL. A 21 year survey of 654 ectopic pregnancies. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1970;106:1004-1019.

Brosens I, Gordts S, Vásquez G, Boeckx W. Function-retaining surgical management of ectopic pregnancy. European Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1984;18:395-402.

Brown DL, Felker RE, Stovall TG, Emerson DS, Ling FW. Serial endovaginal sonography of ectopic pregnancies treated with methotrexate. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1991;77:406-409.

Brown DL, Doubilet PM. Transvaginal sonography for diagnosing ectopic pregnancy: positive criteria and performance characteristics. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 1994;13:259-266.

Cohen DR, Falcone T, Khalife S. Methotrexate: local versus intramuscular. Fertility and Sterility. 1996;65:206-207.

Condous G, Okaro E, Khalid A, et al. The use of a new logistic regression model for predicting the outcome of pregnancies of unknown location. Human Reproduction. 2004;19:1900-1910.

Condous G, Lu C, Van Huffel SV, Timmerman D, Bourne T. Human chorionic gonadotrophin and progesterone levels in pregnancies of unknown location. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2004;86:351-357.

Condous G, Kirk E, Lu C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of varying discriminatory zones for the prediction of ectopic pregnancy in women with a pregnancy of unknown location. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;26:770-775.

Condous G, Kirk E, Van Calster B, Van Huffel S, Timmerman D, Bourne T. Failing pregnancies of unknown location: a prospective evaluation of the human chorionic gonadotrophin ratio. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;113:521-527.

Comstock C, Huston K, Lee W. The ultrasonographic appearance of ovarian ectopic pregnancies. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;105:42-45.

De Muylder X, De Loecker P, Campo R. Heterotopic ovarian pregnancy after clomiphene ovulation induction. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1994;53:65-66.

DeStefano F, Peterson HB, Layde PM. Risk of ectopic pregnancy following tubal sterilization. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1982;60:326-330.

Droegemueller W. Ectopic pregnancy. In Danforth D, editor: Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 4th edn, Philadelphia: Harper and Row, 1982.

Elson J, Salim R, Tailor A, Banerjee S, Zosmer N, Jurkovic D. Prediction of early pregnancy viability in the absence of an ultrasonically detectable embryo. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;21:57-61.

Fernandez H, Bourget P, Ville Y, Lelaidier C, Frydman R. Treatment of unruptured tubal pregnancy with methotrexate: pharmacokinetic analysis of local versus intramuscular administration. Fertility and Sterility. 1994;62:943-947.

Gazvani MR, Emery SJ. Mifepristone and methotrexate: the combination for medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;180:1599-1600.

Ghi T, Giunchi S, Kuleva M, et al. Three-dimensional transvaginal sonography in local staging of cervical carcinoma: description of a novel technique and preliminary results. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;30:778-782.

Goldner TE, Lawson HW, Xia Z, Atrash HK. Surveillance for ectopic pregnancy — United States 1970–1989. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 1993;42:73-85.

Graesslin O, Dedecker FJr, Quereux C, Gabriel R. Conservative treatment of ectopic pregnancy in a cesarean scar. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;105:869-871.

Hahlin M, Wallin A, Sjöblom P, Lindblom B. Single progesterone assay for early recognition of abnormal pregnancy. Human Reproduction. 1990;5:622-626.

Hahlin M, Thorburn J, Bryman I. The expectant management of early pregnancies of uncertain site. Human Reproduction. 1995;10:1223-1227.

Hajenius PJ, Mol F, Mol BW, Bossuyt PM, Ankum WM, van der Veen F 2007 Interventions for tubal ectopic pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1: CD000324.

Harika G, Gabriel R, Carre-Pigeon F, Alemany L, Quereux C, Wahl P. Primary application of three-dimensional ultrasonography to early diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproduction Biology. 1995;60:117-120.

Helmy S, Sawyer E, Ofili-Yebovi D, Yazbek J, Ben Nagi J, Jurkovic D. Fertility outcomes following expectant management of tubal ectopic pregnancy. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2007;30:988-993.

Hofmann HM, Urdl W, Höfler H, Hönigl W, Tamussino K. Cervical pregnancy: case reports and current concepts in diagnosis and treatment. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1987;241:63-69.

Hreschchyshyn MM, Naples JD, Randall CL. Amethopterin in abdominal pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1965;93:286-287.

Hung TH, Shau WY, Hsieh TT, Hsu JJ, Soong YK, Jeng CJ. Prognostic factors for an unsatisfactory primary methotrexate treatment of cervical pregnancy: a quantitative review. Human Reproduction. 1998;13:2636-2642.

Jurkovic D, Bourne TH, Jauniaux E, Campbell S, Collins WP. Transvaginal color Doppler study of blood flow in ectopic pregnancies. Fertility and Sterility. 1992;57:68-73.

Jurkovic D, Hillaby K, Woelfer B, Lawrence A, Salim R, Elson CJ. First-trimester diagnosis and management of pregnancies implanted into the lower uterine segment Cesarean section scar. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;21:220-227.

Jurkovic D, Ben-Nagi J, Ofilli-Yebovi D, Sawyer E, Helmy S, Yazbek J. Efficacy of Shirodkar cervical suture in securing hemostasis following surgical evacuation of Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;30:95-100.

Jurkovic D, Mavrelos D. Catch me if you scan: ultrasound diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;30:1-7.

Kadar N, Caldwell BV, Romero R. A method of screening for ectopic pregnancy and its indications. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1981;58:162-166.

Kadar N, Romero R. Serial human chorionic gonadotrophin measurements in ectopic pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1988;158:1239-1240.

Kirk E, Condous G, Haider Z, Syed A, Ojha K, Bourne T. The conservative management of cervical ectopic pregnancies. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;27:430-437.

Kirk E, Papageorghiou AT, Condous G, Tan L, Bora S, Bourne T. The diagnostic effectiveness of an initial transvaginal scan in detecting ectopic pregnancy. Human Reproduction. 2007;22:2824-2828.

Knoll M, Talbot P. Cigarette smoke inhibits oocyte cumulus complex pick-up by the oviduct ciliary beat frequency. Reproductive Toxicology. 1998;12:57-68.

Kung FT, Chang SY. Efficacy of methotrexate treatment in viable and nonviable cervical pregnancies. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;181:1438-1444.

The Seventh Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. Lewis G, editor. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving Mother’s Lives: Reviewing Maternal Deaths to Make Motherhood Safer — 2003–2005. London: CEMACH, 2007.

Li MC, Nerts R, Spence DB. Effect of methotrexate therapy on choriocarcinoma and chorioadenoma. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 1956;93:361-366.

Lundorff P, Thorburn J, Hahlin M, Källfelt B, Lindblom B. Laparoscopic surgery in ectopic pregnancy. A randomized trial versus laparotomy. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1991;70:343-348.

Marchbanks PA, Coulman CB, Annegers JF. An association between clomiphene citrate and ectopic pregnancy: a preliminary report. Fertility and Sterility. 1985;44:268-270.

Marchiolé P, Gorlero F, de Caro G, Podestà M, Valenzano M. Intramural pregnancy embedded in a previous Cesarean section scar treated conservatively. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;23:307-309.

Marcus SF, Brinsden PR. Primary ovarian pregnancy after in vitro fertilisation and embryo transfer: report of seven cases. Fertility and Sterility. 1993;60:167-169.

Mathews CP, Coulson PB, Wild RA. Serum progesterone levels as an aid in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1986;68:390-394.

McBain JC, Evans JH, Pepperell RJ, Robinson HP, Smith MA, Brown JB. An unexpectedly high rate of ectopic pregnancy following the induction of ovulation with human pituitary and chorionic gonadotrophin. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1980;87:5-9.

Mol BW, Lijmer JG, Ankum WM, van der Veen F, Bossuyt PM. The accuracy of single serum progesterone measurement in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Human Reproduction. 1998;13:3220-3227.

Oki T, Baba Y, Yoshinaga M, Douchi T. Super-selective arterial embolization for uncontrolled bleeding in abdominal pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;112:427-429.

Ory HW. Ectopic pregnancy and intrauterine contraceptive devices: new perspectives. The Women’s Health Study. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1981;57:137-144.

O’Shea RT, Thompson GR, Harding A. Intra-amniotic methotrexate versus CO2 laser laparoscopic salpingotomy in the management of tubal ectopic pregnancy — a prospective randomized trial. Fertility and Sterility. 1994;62:876-878.

Perdu M, Camus E, Rozenberg P, et al. Treating ectopic pregnancy with the combination of mifeperistone and methotrexate: a phase II nonrandomized study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;179:640-643.

Persaud V. Etiology of tubal ectopic pregnancy. Radiologic and pathologic studies. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1970;36:257-263.

Peterson HB, Xia Z, Hughes JM, Wilcox LS, Tylor LR, Trussell J. The risk of ectopic pregnancy after tubal sterilization. U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization Working Group. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;336:762-767.

Pittaway DE, Reish RL, Wentz AC. Doubling times of human chorionic gonadotropin increase in early viable intrauterine pregnancies. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1985;152:299-302.

Pouly J, Chapron C, Mage G, et al. The drop in the level of HCG after conservative laparoscopic treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Journal of Gynaecological Surgery. 1991;7:211-217.

Rajkhowa M, Glass MR, Rutherford AJ, Balen AH, Sharma V, Cuckle HS. Trends in the incidence of ectopic pregnancy in England and Wales from 1966 to 1996. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;107:369-374.

Rempen A. The shape of the endometrium evaluated with three-dimensional ultrasound: an additional predictor of extrauterine pregnancy. Human Reproduction. 1998;13:450-454.

Romero R, Kadar N, Jeanty P, et al. Diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy: value of the discriminatory human chorionic gonadotropin zone. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1985;66:357-360.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The Management of Tubal Pregnancy. Guideline No. 21. RCOG, London, 2004.

Sau A, Hamilton-Fairley D. Non surgical diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. Obstetrician and Gynaecologist. 2003;5:29-33.

Sauer M, Vidali A, James W. Treating persistent ectopic pregnancy by methotrexate using a sliding scale: preliminary experience. Journal of Gynaecological Surgery. 1997;13:13-16.

Seeber BE, Sammel MD, Guo W, Zhou L, Hummel A, Barnhart KT. Application of redefined human chorionic gonadotropin curves for the diagnosis of women at risk for ectopic pregnancy. Fertility and Sterility. 2006;86:454-459.

Shalev E, Peleg D, Bustan M, Romano S, Tsabari A. Limited role for intratubal methotrexate treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Fertility and Sterility. 1995;63:20-24.

Shaw SW, Hsu JJ, Chueh HY, et al. Management of primary abdominal pregnancy: twelve years of experience in a medical centre. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2007;86:1058-1062.

Silva P, Schaper A, Rooney B. Reproductive outcome after 143 laparoscopic procedures for ectopic pregnancy. Fertility and Sterility. 1993;81:710-715.

Silva C, Sammel MD, Zhou L, Gracia C, Hummel AC, Barnhart K. Human chorionic gonadotrophin profile for women with ectopic pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;107:605-610.

Singhal V, Li TC, Cooke ID. An analysis of factors influencing the outcome of 232 consecutive tubal micro surgery cases. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1991;98:628-636.

Smith HO, Toledo AA, Thompson JD. Conservative surgical management of isthmic ectopic pregnancies. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1987;157:604-610.

Sowter MC, Farquhar CM, Petrie KJ, Gudex G. A randomised trial comparing single dose systemic methotrexate and laparoscopic surgery for the treatment of unruptured tubal pregnancy. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2001;108:192-203.

Spiegelberg O. Zur Casuistik der Ovarialschwangerschaft. Archives of Gynecology. 1878;13:73-77.

Stabile I. Clinical presentation of ectopic pregnancy. In: Stabile I, editor. Ectopic Pregnancy: Diagnosis and Management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Stabile I. Biochemical diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. In: Stabile I, editor. Ectopic Pregnancy: Diagnosis and Management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Stovall TG. Medical management should be routinely used as primary therapy for ectopic pregnancy. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;38:346-352.

Stovall TG, Ling FW. Ectopic pregnancy. Diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms minimizing surgical intervention. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 1993;38:807-812.

Svare J, Norup P, Grove Thomsen S, et al. Heterotopic pregnancies after in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer in a Danish survey. Human Reproduction. 1993;8:116-118.

Tanaka T, Hayashi H, Kutsuzawa T, Fujimoto S, Ichinoe K. Treatment of interstitial ectopic pregnancy with methotrexate: report of a successful case. Fertility and Sterility. 1982;37:851-852.

Tharaux-Deneux C, Bouyer J, Job-Spira N, Coste J, Spira A. Risk of ectopic pregnancy and previous induced abortion. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:401-405.

Tulandi T, Guralnick M. Treatment of tubal ectopic pregnancy by salpingotomy with or without tubal suturing and salpingectomy. Fertility and Sterility. 1991;55:53-55.

Tulandi T, Vilos G, Gomel V. Laparoscopic treatment of interstitial pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;85:465-467.

Vessey MP, Johnson B, Doll R, Peto R. Outcome of pregnancy in women using an intrauterine device. The Lancet. 1974;1:495-498.

Westrom L, Bengtsson LP, Mardh PA. Incidence, trends and risks of ectopic pregnancy in a population of women. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1981;282:15-18.

Weyerman PC, Verhoeven AT, Alberda AT. Cervical pregnancy after in vitro fertilisation and embryo transfer. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1989;161:1145-1146.

Wollen AL, Flood PR, Sandvei R, Steier JA. Morphological changes in tubal mucosa associated with the use of intrauterine contraceptive devices. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1984;91:1123-1128.

Yao M, Tulandi T. Current status of surgical and nonsurgical management of ectopic pregnancy. Fertility and Sterility. 1997;67:421-433.