10

Early pregnancy care

Miscarriage

Miscarriage is common, occurring in as many as 20% of all pregnancies. It is very upsetting for the parents and considerable sensitivity is required. Clinical management should ideally take place in an early pregnancy unit and be founded on two important principles:

1. Until the diagnosis of a non-continuing pregnancy is confirmed, a wait and see approach should be adopted, remembering that dates may be incorrect.

2. There should be a low threshold of suspicion for ectopic pregnancy. The absence of an ectopic pregnancy on ultrasound scanning does not mean that there is not an ectopic pregnancy.

Definition

Miscarriage can be defined according to the gestation or the weight of the fetus. The World Health Organization (WHO) definition is, ‘the expulsion from its mother of an embryo or fetus weighing 500 g or less’ (500 g is approximately the 50th centile for 20 weeks’ gestation). The term ‘abortion’ has connotations of induced abortion and should not be used in connection with spontaneous pregnancy loss, where ‘miscarriage’ is appropriate.

In the UK, any pregnancy loss before 24 weeks is regarded as a miscarriage, and any fetus born dead at or after 24 weeks’ gestation is registered as a stillbirth. If a fetus shows signs of life after delivery at any gestation but subsequently dies, the loss is registered as a live birth and subsequent neonatal death.

There is therefore a discrepancy between the legal definition used in the UK and the internationally accepted definition. Because of the rapid advances in neonatal intensive care and the survival of babies born at 23 weeks, most modern epidemiological studies follow the WHO guideline and confine the definition to losses occurring before 20 weeks.

A threatened miscarriage is where bleeding occurs but the pregnancy may be continuing, whereas in an inevitable miscarriage, there is bleeding and the pregnancy is not continuing. The cervix may be dilated.

The diagnosis should be confirmed by ultrasound scan unless the patient is clinically shocked and requires immediate surgery. The management depends on the scan findings, irrespective of cervical findings.

![]() incomplete: passage of some, but not all, of the pregnancy tissue

incomplete: passage of some, but not all, of the pregnancy tissue

![]() complete: all pregnancy tissue has been expelled from the uterus

complete: all pregnancy tissue has been expelled from the uterus

![]() delayed/missed (silent): where the fetus has died in utero before 24 weeks but has not been expelled; ‘anembryonic pregnancy’ is a type of ‘missed’ miscarriage, in which embryonic development fails at a very early stage in the pregnancy

delayed/missed (silent): where the fetus has died in utero before 24 weeks but has not been expelled; ‘anembryonic pregnancy’ is a type of ‘missed’ miscarriage, in which embryonic development fails at a very early stage in the pregnancy

![]() septic: a complication of incomplete miscarriage or therapeutic (sometimes illegal) abortion, when intrauterine infection occurs

septic: a complication of incomplete miscarriage or therapeutic (sometimes illegal) abortion, when intrauterine infection occurs

![]() recurrent: three or more consecutive miscarriages.

recurrent: three or more consecutive miscarriages.

Incidence

As noted above, the incidence of miscarriage is about 20% and is highest in early pregnancy, but falls to < 1% after the end of the first trimester. Evidence from studies of chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) assays in very early pregnancy and from assisted conception units suggests that rates of very early miscarriage may be as high as 50–60%.

The incidence of miscarriage has been shown to increase with maternal age, rising by a factor of 10 after the age of 40 years compared with before 35 years. Overall, however, when the fetus is found to be viable on an ultrasound scan, the chance of a successful outcome is high (< 5% risk of miscarriage once fetal heart seen).

Recurrence risk

This knowledge is important for parental counselling. Only a very few women have a specific recurring cause and it is reasonable to reassure the couple that the outlook for future pregnancies is good. A woman experiencing a first miscarriage does not necessarily have an increased risk of miscarriage in her next pregnancy.

Aetiology

There are a number of conditions recognized as causing sporadic and/or recurrent miscarriage.

Fetal chromosomal abnormalities

About half of all clinically recognized first-trimester losses are chromosomally abnormal, with 50% of these being autosomal trisomy; 20% 45XO monosomy; 20% polyploidy and 10% with various other abnormalities. In second-trimester miscarriage, the incidence of chromosomal abnormality is lower, at about 20% overall.

Immunological causes

Autoimmune disease

Approximately 15% of women who are investigated for recurrent miscarriage (three or more consecutive pregnancy losses) are found to be positive for lupus anticoagulant, antiphospholipid antibodies or both. Untreated, they have a subsequent rate of fetal loss approaching 70–80%. Effective treatment can be provided with low-dose aspirin and low-molecular-weight heparin. These antibodies are also associated with arterial and venous thrombosis, fetal growth restriction, pre-eclampsia and thrombocytopenia, and this should be borne in mind for later pregnancy management. The lupus anticoagulant is not synonymous with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), being present in only 5–15% of patients with SLE.

Alloimmune disease

It is possible that recurrent miscarriage is caused by some immunological problem at the interface between trophoblastic cells and maternal cells, although the exact nature of this proposed problem has not been clearly elucidated. There has been interest in endometrial NK cells (natural killer cells) which were originally thought to be the cause of miscarriage, but a more recent hypothesis suggests that they might have a role in rejecting abnormal embryos and allowing the normal ones to thrive. Inadequate NK function would result in increased fertility (which is not uncommon in recurrent miscarriage) but also increased loss of embryos that do not make it beyond a certain point because of their abnormality. There is a suggestion that steroids may be of benefit in treating this condition however further research is required.

Endocrine factors

Women with polycystic ovary syndrome have an increased incidence of both sporadic and recurrent miscarriage and, although this has been attributed to high circulating levels of luteinizing hormone in the follicular phase of the cycle, there is no evidence of any effective therapy. Inadequate luteal function has been reported in association with recurrent miscarriage in 20–60% of cases, but there is no convincing evidence to support the use of artificial progestogens.

In women with diabetes mellitus who have poor control around the time of conception, the incidence of miscarriage is high at around 45%. Women whose control is good are no more likely to have a miscarriage than those who do not have diabetes. There is no clear association between thyroid dysfunction and miscarriage, unless this is poorly controlled.

Uterine anomalies

Structural uterine anomalies, such as bicornuate or septate uteri, may cause miscarriage, but this is by no means certain. Uterine fibroids may also interfere with early pregnancy growth, but the extent to which they cause miscarriage is difficult to determine because of other associated factors, such as age, hormonal dysfunction and subfertility.

Infections

Any serious maternal infection causing high fever at any time in pregnancy may adversely affect the fetus and lead to pregnancy loss. There are also a number of specific maternal infections, such as rubella and cytomegalovirus, which cross the placenta and affect the placenta and fetus. Such congenital infection in early pregnancy may lead to miscarriage, as well as to later fetal abnormality and neonatal illness. Malaria, trypanosomiasis, mycoplasma, Listeria monocytogenes and syphilis have also all been implicated in early pregnancy loss. These are unlikely to cause recurrent loss.

Environmental pollutants

Cigarette smoking, both active and passive, and high alcohol consumption are associated with slightly higher rates of sporadic and recurrent miscarriage.

Unexplained

At least 50% of miscarriages, either sporadic or recurrent, have no identifiable cause.

Clinical presentation and management

Presentation

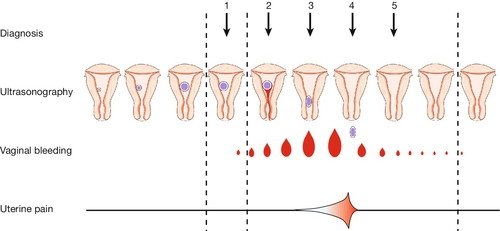

There is usually a history of bleeding per vaginam (p.v.) and lower abdominal pain. The passage of tissue is sometimes reported (Fig. 10.1). The bleeding can vary from being life-threateningly severe, requiring urgent and aggressive resuscitation to the smallest brown spotting.

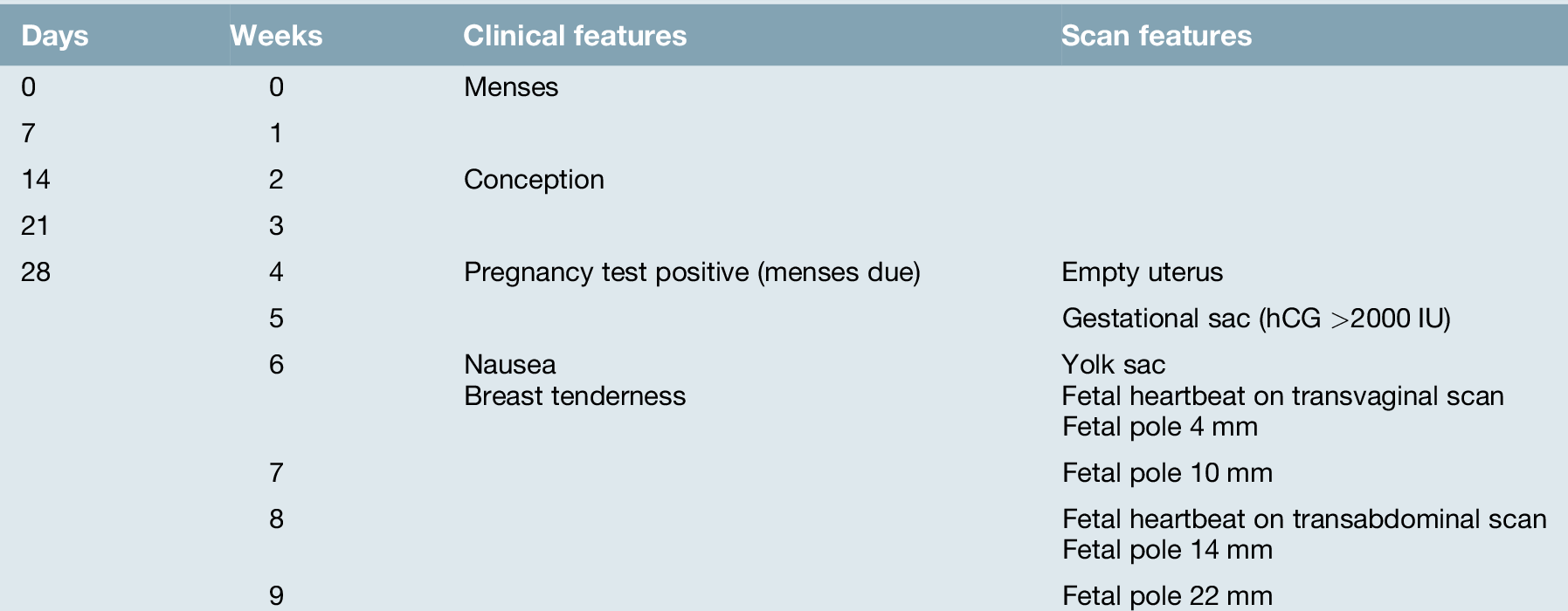

Fig. 10.1Clinical and ultrasound features of a miscarriage.

1. Ultrasound may show fetal heart activity or the pregnancy may appear non-viable. 2. Vaginal bleeding and pain begin. 3. The cervical os is open – an inevitable miscarriage. 4. The gestational sac is extruded. 5. Pain and bleeding usually settle rapidly.

Occasionally, there may be no symptoms at all and an empty gestational sac, or fetal pole with absent fetal heartbeat, may be found at a routine booking scan (missed or delayed miscarriage). It is seldom possible to make consistently reliable diagnoses based on clinical examination alone and, as noted above, management is largely based on ultrasound scan (USS) findings. This management relies on an understanding of the ultrasound findings in a normally developing pregnancy (Table 10.1). Ultrasound is usually commenced transabdominally, but the transvaginal (TVS) approach provides superior images and is widely employed.

Viable intrauterine pregnancy

The prognosis is good and the parents can be offered reasonable reassurance (Fig. 10.2). If there are recurrent bleeds, however, the pregnancy may be considered as high risk.

Fig. 10.2An intrauterine 22 mm fetal pole, consistent with 9 weeks’ gestation.

Fetal heart activity was seen.

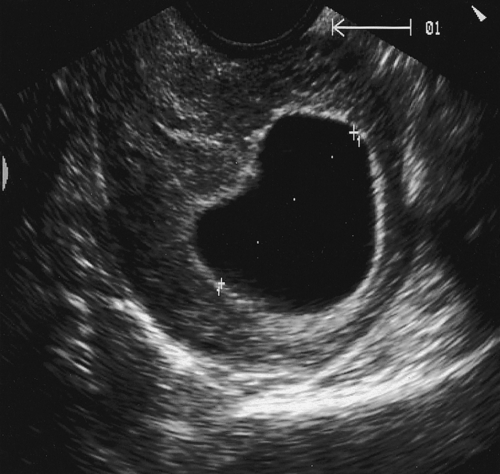

Empty gestational sac

If there is an empty gestational sac on TVS with an average diameter > 25 mm, the pregnancy is very likely to be non-viable (Fig. 10.3). If a pregnancy test was positive more than 3 weeks previously, the gestation is likely to be at least 6 + weeks and a fetal pole would always be expected on transvaginal (TV) ultrasound scanning. If the first positive pregnancy test was less than 3 weeks previously, however, conservative management is most appropriate, with a repeat scan in at least 10 days. Although this will add anxious waiting time for the mother, it is essential to ensure the pregnancy is definitely not continuing.

Fig. 10.3An empty gestational sac at 8 weeks’ gestation.

This pregnancy was an anembryonic, sometimes referred to as a ‘silent’, miscarriage.

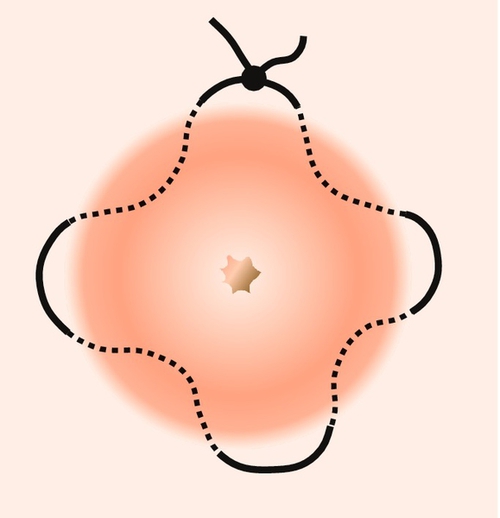

A true gestational sac should be differentiated from a ‘pseudosac’ (Fig. 10.4). This is caused by fluid secreted under the hCG stimulation of an ectopic pregnancy, and it lacks the ‘double decidual ring’ outline seen with a true sac (see Figs 10.3 and 10.5).

Fig. 10.5Intrauterine gestational scan containing a 6 mm fetal pole with a yolk sac.

There was no fetal heart activity on transvaginal scan. Note the double decidual ring consistent with intrauterine pregnancy.

Fetal pole with no fetal heartbeat

A fetal heartbeat is usually seen on a TV scan if the fetal pole is more than 2–3 mm, but will always be seen by 7 mm (Fig. 10.5) if present (15 mm is appropriate for a transabdominal scan). If there is any doubt, re-scanning should be arranged in 7–10 days.

Empty uterus

Either there has been a complete miscarriage (tissue may have been passed), or the pregnancy is very early (e.g. < 5 weeks), or there is an ectopic pregnancy. Ectopic pregnancy must be excluded. An intrauterine sac will usually be seen on TV scan if the hCG is > 1000 IU, and its absence raises the possibility of an ectopic pregnancy. Serum levels of hCG should rise by more than 66% in 48 h if the pregnancy is viable and intrauterine; a smaller rise suggests an ectopic pregnancy (see Fig. 10.7). If the level doubles and the woman remains well, the ultrasound scan should be repeated in 1 week to ensure that the pregnancy is ongoing. If less than doubling, steady, or only slightly reduced, continued monitoring of hCG levels should be performed and consideration given to medical management if an ectopic pregnancy or pregnancy of unknown location is diagnosed (PUL). Alternatively, a laparoscopy may be required if the woman is clinically unstable or a significant amount of free fluid is seen in the Pouch of Douglas on scan (see below).

Gestational trophoblastic disease

See Chapter 21.

Management of early pregnancy loss

This should ideally take place in an early pregnancy unit, run by dedicated caring staff. Once a diagnosis has been established and explained to the woman and her partner, providing there is no ongoing heavy vaginal bleeding, the options of conservative, medical or surgical management can be discussed. Surgical management of miscarriage (SMM) and medical management (MMM) with or without mifepristone (depending upon gestation) and a synthetic prostaglandin are technically analogous to the methods employed in the therapeutic termination of pregnancy (Chapter 26). The benefits and risks should be discussed prior to consent being obtained. Conservative management with no scheduled medical or surgical intervention may also be appropriate, but the woman needs to be warned that the onset, duration and magnitude of the inevitable vaginal bleeding are unpredictable. If the diameter of retained products is small on ultrasound examination (e.g. < 40 mm) and the woman wishes conservative management, she may be asked to perform a pregnancy test in 3 weeks. If this is still positive, she should phone her early pregnancy unit for review. Alternatively, a repeat scan may be arranged. A small number of women may have retained pregnancy tissue and should then be offered surgical or medical management as outlined.

Rhesus isoimmunization

Rhesus isoimmunization may occur in rhesus-negative women who have lost a rhesus-positive fetus (Chapter 39). As there is no practical way of determining fetal blood group in miscarriage, all rhesus-negative women should be offered anti-D immunoglobulin as appropriate:

![]() confirmed miscarriage: anti-D should be given to all non-sensitized rhesus-negative women who miscarry after 12 weeks, whether complete or incomplete, and to those who miscarry below 12 weeks when the uterus is surgically evacuated

confirmed miscarriage: anti-D should be given to all non-sensitized rhesus-negative women who miscarry after 12 weeks, whether complete or incomplete, and to those who miscarry below 12 weeks when the uterus is surgically evacuated

![]() threatened miscarriage: anti-D should be given to all non-sensitized rhesus-negative women with threatened miscarriage after 12 weeks. Routine administration of anti-D is not required below 12 weeks when the fetus is viable, unless the bleeding is heavy or associated with abdominal pain. If there is clinical doubt, then anti-D should be given.

threatened miscarriage: anti-D should be given to all non-sensitized rhesus-negative women with threatened miscarriage after 12 weeks. Routine administration of anti-D is not required below 12 weeks when the fetus is viable, unless the bleeding is heavy or associated with abdominal pain. If there is clinical doubt, then anti-D should be given.

After the miscarriage

There has been a bereavement; the emotional trauma experienced will vary from one couple to the next, but the negative impact of a miscarriage should not be underestimated. Information about support groups, such as The Miscarriage Association, should be given to all women at the time of pregnancy loss.

Sepsis

Fortunately, this is rare, most frequently being encountered after termination of pregnancy in countries where abortion is illegal, but sometimes occurring after a spontaneous miscarriage, especially in the presence of retained pregnancy tissue. There is usually pyrexia, tachycardia, malaise, abdominal pain, marked tenderness and a purulent vaginal loss. Endotoxic shock may develop, which has a significant maternal mortality. The responsible organisms include Gram-negative bacteria, streptococci (haemolytic and anaerobic) and other anaerobes (e.g. Bacteroides). Treatment is with fluid resuscitation, appropriate antibiotics and ensuring that the uterus is empty of any retained pregnancy tissue.

Recurrent miscarriage

This is the consecutive loss of three or more pregnancies < 24 weeks’ gestation. The incidence is 1%, which is greater than would be expected by chance alone (estimated at 0.34%). Only a proportion of women will therefore have an underlying cause for their recurrent losses.

Investigation is based on the principles discussed above and includes:

![]() karyotype from both parents – the incidence of chromosomal abnormality in this group, usually a balanced translocation, is around 3–5%. The finding of such an abnormality should prompt genetic referral since it has implications for future pregnancies

karyotype from both parents – the incidence of chromosomal abnormality in this group, usually a balanced translocation, is around 3–5%. The finding of such an abnormality should prompt genetic referral since it has implications for future pregnancies

![]() maternal blood for lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies, to look for antiphospholipid syndrome (see above)

maternal blood for lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies, to look for antiphospholipid syndrome (see above)

![]() thrombophilia screen – retrospective studies have indicated an increased incidence of thrombophilic defects in those with recurrent miscarriage (activated protein C resistance, antithrombin III deficiency, protein C deficiency, and protein S deficiency, and possibly hyperhomocystinaemia). Evidence for effective treatment in this group is lacking, and the value of this investigation is open to question

thrombophilia screen – retrospective studies have indicated an increased incidence of thrombophilic defects in those with recurrent miscarriage (activated protein C resistance, antithrombin III deficiency, protein C deficiency, and protein S deficiency, and possibly hyperhomocystinaemia). Evidence for effective treatment in this group is lacking, and the value of this investigation is open to question

![]() pelvic ultrasound scan (uterus and ovaries) to look for uterine abnormalities. It is very difficult, however, to estimate the significance of any anatomical abnormalities and caution is required before undertaking any surgery as it is possible to do more harm than good. It may also be appropriate to consider a hysterosalpingogram to look for uterine anomalies but probably only with second trimester losses and, again, the uncertain significance of any identified anomalies make the results difficult to interpret.

pelvic ultrasound scan (uterus and ovaries) to look for uterine abnormalities. It is very difficult, however, to estimate the significance of any anatomical abnormalities and caution is required before undertaking any surgery as it is possible to do more harm than good. It may also be appropriate to consider a hysterosalpingogram to look for uterine anomalies but probably only with second trimester losses and, again, the uncertain significance of any identified anomalies make the results difficult to interpret.

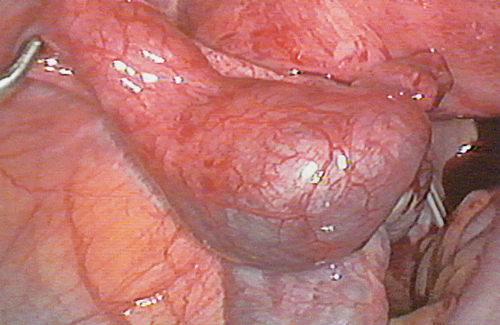

Among women with mid-trimester loss, the possibility of cervical weakness should be considered. Cervical weakness indicates that the internal os of the cervix is unable to retain the pregnancy within the uterus. The diagnosis is supported by a history of relatively painless cervical dilatation, and there may be a background history of prior surgery to the cervix. There is no single diagnostic test of cervical weakness, which makes reliable diagnosis impossible. Inserting a cervical suture (cervical cerclage) may be of benefit, but at the risk of infection developing after insertion (Fig. 10.6). Transabdominal cerclage is also used where a vaginal approach either has been technically not possible due to the short length of the cervix or a vaginally placed suture has failed.

Where no specific abnormalities are found, counselling and reassurance are the mainstays of successful management: 60–75% of women who have suffered three consecutive miscarriages and who have no apparent underlying cause will have a successful pregnancy at their next attempt. The use of unproven treatments should be resisted. Research into therapies is ongoing, including the administration of progesterone (the PROMISE study).

Ectopic pregnancy

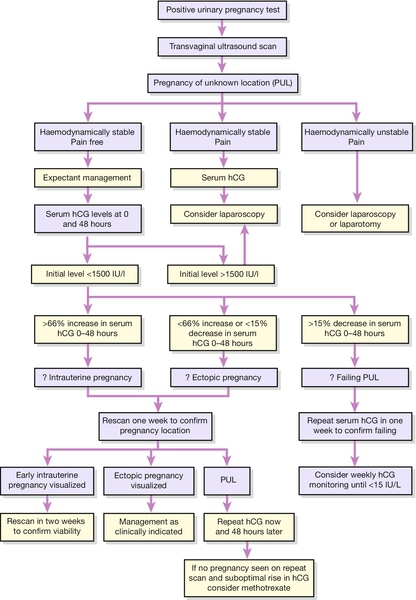

Although non-intrauterine pregnancies can be ovarian, cervical or intra-abdominal, the majority are tubal (Fig. 10.7). The incidence of ectopic pregnancy is 1 in 200 and it remains one of the major causes of maternal mortality.

The history and examination should particularly include the date of the last menstrual period, the date of any pregnancy tests and symptoms suggesting pelvic infections. Symptoms of PV bleeding, abdominal pain, shoulder tip pain and bowel upset are important. Pelvic examination should be gentle to avoid tubal rupture. If the pregnancy test is positive and the woman is not shocked, an ultrasound scan (often transvaginal) will be helpful to distinguish between ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage and continuing intrauterine pregnancy. A pseudosac (fluid in the thickened endometrium) can be confused with an intrauterine gestation sac in 20% of ectopic pregnancies. A serum beta human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) level, which does not increase by over 66% in 48 h increases the likelihood of ectopic pregnancy.

Management depends on the overall clinical picture, the scan result and the serum level of hCG. Tubal pregnancy can be managed by laparotomy, operative laparoscopy, medically or occasionally, by observation alone. Management must be tailored to the clinical condition and future fertility preferences of the woman (Fig. 10.8).

![]() If the woman is shocked on admission, an immediate pregnancy test should be performed to exclude ectopic pregnancy, with consideration given to urgent surgery if the result is positive. Resuscitation and sometimes blood transfusion will be required.

If the woman is shocked on admission, an immediate pregnancy test should be performed to exclude ectopic pregnancy, with consideration given to urgent surgery if the result is positive. Resuscitation and sometimes blood transfusion will be required.

![]() If the pregnancy test is positive with clinical signs of ectopic pregnancy (pelvic tenderness and/or cervical excitation and/or shoulder tip pain due to diaphragmatic irritation from haemoperitoneum) and an empty uterus on ultrasound, a diagnostic laparoscopy should be carried out. In the presence of an ectopic pregnancy, laparoscopic salpingectomy or salpingotomy is appropriate. In a haemodynamically stable woman, a laparoscopic approach to the surgical management of tubal pregnancy is preferable to an open approach. In the presence of a healthy contralateral tube, there is no clear evidence that salpingotomy should be preferred to salpingectomy. Postoperative tracking of serum hCG is necessary following salpingotomy, to identify the small number of cases complicated by persistent trophoblast.

If the pregnancy test is positive with clinical signs of ectopic pregnancy (pelvic tenderness and/or cervical excitation and/or shoulder tip pain due to diaphragmatic irritation from haemoperitoneum) and an empty uterus on ultrasound, a diagnostic laparoscopy should be carried out. In the presence of an ectopic pregnancy, laparoscopic salpingectomy or salpingotomy is appropriate. In a haemodynamically stable woman, a laparoscopic approach to the surgical management of tubal pregnancy is preferable to an open approach. In the presence of a healthy contralateral tube, there is no clear evidence that salpingotomy should be preferred to salpingectomy. Postoperative tracking of serum hCG is necessary following salpingotomy, to identify the small number of cases complicated by persistent trophoblast.

![]() In a well woman with a positive UPT and an empty uterus on transvaginal ultrasound, a serum hCG level is performed. This should be repeated after 48 h, and if an ectopic pregnancy is likely and the woman remains asymptomatic, medical management may be considered (up to 3000 IU/L).

In a well woman with a positive UPT and an empty uterus on transvaginal ultrasound, a serum hCG level is performed. This should be repeated after 48 h, and if an ectopic pregnancy is likely and the woman remains asymptomatic, medical management may be considered (up to 3000 IU/L).

![]() Medical therapy with methotrexate, either as a single- or multiple-dose regimen, is an option for women with ectopic pregnancy, who have minimal symptoms, are clinically stable and have a serum hCG level of < 3000 IU/L. If medical therapy is offered, women should be given verbal and written information about the possible need for further treatment, the need to avoid pregnancy for 3 months after the last dose of methotrexate, adverse effects following treatment. Women should be able to return easily for assessment at any time during follow-up.

Medical therapy with methotrexate, either as a single- or multiple-dose regimen, is an option for women with ectopic pregnancy, who have minimal symptoms, are clinically stable and have a serum hCG level of < 3000 IU/L. If medical therapy is offered, women should be given verbal and written information about the possible need for further treatment, the need to avoid pregnancy for 3 months after the last dose of methotrexate, adverse effects following treatment. Women should be able to return easily for assessment at any time during follow-up.

![]() Surgery should be considered for women who have an adnexal mass > 4 cm; an ectopic with a positive fetal heart; significant free fluid in the Pouch of Douglas; serum hCG > 3000 IU/L (depending upon local guideline) or symptoms consistent with pain or bleeding from an ectopic pregnancy.

Surgery should be considered for women who have an adnexal mass > 4 cm; an ectopic with a positive fetal heart; significant free fluid in the Pouch of Douglas; serum hCG > 3000 IU/L (depending upon local guideline) or symptoms consistent with pain or bleeding from an ectopic pregnancy.

![]() Expectant management is an option for clinically stable asymptomatic women with an ultrasound diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy and a decreasing serum hCG, initially less than 1500 IU/L.

Expectant management is an option for clinically stable asymptomatic women with an ultrasound diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy and a decreasing serum hCG, initially less than 1500 IU/L.

When serum hCG levels are below the discriminatory zone (< 1000 IU/L) and there is no pregnancy (intra- or extrauterine) visible on transvaginal ultrasound scan, the pregnancy can be described as being of unknown location (pregnancy of unknown location or PUL). Using an initial upper level of serum hCG of 1000–1500 IU/L to diagnose PUL, women with minimal or no symptoms but at risk of ectopic pregnancy should be managed expectantly with 48-h follow-up and should be considered for active intervention if symptoms of ectopic pregnancy occur, serum hCG levels rise above the discriminatory level (1500 IU/L) or levels start to plateau. Conservative management is particularly appropriate in those with a low progesterone level (< 20 nmol/L). Intervention has been shown to be required in 20–30% of cases of PUL. If women are managed expectantly, serial serum hCG measurements should be performed until hCG levels are < 5 or 15 IU/L. In addition, women selected for expectant management of PUL should be given clear information about the importance of compliance with follow-up and should be within easy access of the unit treating them.

Non-sensitized women who are rhesus negative with a confirmed or suspected ectopic pregnancy, should receive anti-D immunoglobulin.

Conclusion

For most miscarriages, whether sporadic or recurrent, no specific cause can be found. Competent management of the acute episode, supportive care and timely investigation of women with recurrent miscarriage are the mainstays of treatment.