27 Ear Emergencies

• Ears are exquisitely sensitive organs. Treating pain is important in caring for patients with ear problems and will facilitate performance of the examination.

• Simple otitis externa can be treated with topical medications and débridement.

• Many cases of uncomplicated otitis media resolve spontaneously. Watchful waiting with use of a “rescue” antibiotic prescription has been shown to decrease unnecessary antibiotic use and improve patient and parent satisfaction.

• Subtle malalignments or malformations after repair of ear trauma can have profound cosmetic consequences.

• Pain from the teeth, pharynx, or temporomandibular joint or from cranial or cervical neuropathies can be referred to the ear.

• Hearing loss must be categorized as conductive or sensorineural. Conductive lesions can often be diagnosed clinically. Sensorineural hearing loss requires urgent referral to an otolaryngologist to improve the chance for recovery of hearing.

Ear Pain

Infections

Otitis Externa

The diagnosis of external otitis is made from the history and findings of pain, pruritus, canal irritation, and edema on physical examination. Thick greenish discharge suggests Pseudomonas, whereas golden crusting implicates S. aureus. Other colored or black discharge may indicate fungal infections, of which Candida and Aspergillus are the most commonly isolated species.1 Small abscesses in the external ear canal can cause obstruction. These abscesses often require incision and drainage, as well as standard treatment of otitis externa.

Treatment

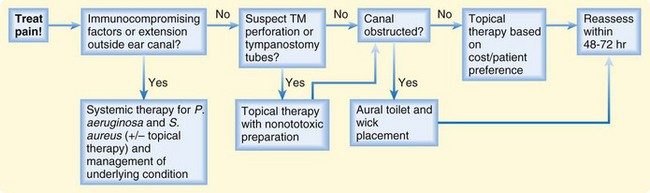

Treatment consists of débridement or aural toilet and antibiotics. Despite a relative lack of controlled studies, the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation has released clinical practice guidelines based on evidence available as of 2005 (Fig. 27.1; also see the Patient Teaching Tips box).2 Briefly, these guidelines are as follows:

1. Distinguish acute external otitis from other causes of otalgia, otorrhea, and inflammation. Diagnostic criteria include rapid onset (2 to 3 days) and a duration of less than 3 weeks. Symptoms include otalgia, itching, or fullness. Signs include tenderness of the pinna or tragus or visual evidence of canal erythema, edema, or otorrhea.

2. Assess for factors that may complicate the disease or treatment (e.g., perforation of the tympanic membrane or eustachian tubes, immunocompromising states, previous radiotherapy). These factors raise the level of treatment needed and heighten suspicion for more invasive disease states such as necrotizing otitis externa (see later). These guidelines pertain to patients older than 2 years with normal states of health.

3. Pay attention to assessment and treatment of pain! Mild to moderate pain usually responds to acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug alone or in combination with an opioid.

4. Topical preparations are first-line agents for the treatment of acute uncomplicated otitis externa. Reserve systemic therapy for immunocompromised patients or extension of disease beyond the ear canal. Topical therapy produces drug concentrations 100 to 1000 times that available with systemic administration and can thus overwhelm resistance mechanisms. No clear evidence points to the superiority of one particular treatment. Antiseptic and acidifying agents (e.g., aluminum acetate and boric acid) appear to work as well as antibiotic-containing solutions (e.g., solutions that contain cortisone and Neosporin or a fluoroquinolone). Corticosteroids in the drops decrease the duration of pain by approximately 1 day.3

5. Make sure that the patient can instill the drops correctly. Edema can prevent the drops from entering the canal. Debris or detritus should be removed or irrigated out. Placement of a compressed cellulose or ribbon gauze wick in the canal will enable the drops to penetrate, but placement can be painful. Within 1 to 2 days the canal edema should subside, and the wick falls out or can be removed (Fig. 27.2).

6. If you cannot be sure that the tympanic membrane is intact, use a nonototoxic, pH-balanced preparation such as ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin-dexamethasone.

7. Educate and reassess your patients. Pain should decrease significantly in 1 to 2 days and resolve by 4 to 7 days. Failure to improve may indicate more invasive disease (e.g., necrotizing otitis), inability of drops to reach the canal (wick needed), or noncompliance with therapy.

Fig. 27.1 Algorithm for the treatment of acute otitis externa.

(Adapted from Rosenfeld RM, Brown L, Cannon CR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;134;S4-23.)

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Otitis Externa

Most patients with otitis externa can be managed as outpatients. Follow-up in 1 to 2 days is indicated if a wick is placed for treatment, if oral antibiotic therapy is started, or if the pain does not begin to resolve in 24 to 36 hours.

Patients should discontinue use of the drops after full resolution of their symptoms. Continued use of antibiotics (especially neomycin) can predispose to changes in the environment of the ear canal and foster fungal infections or sensitivity reactions.

Patients must avoid getting water in the ear during the healing process. Cotton balls soaked in petroleum jelly work well as earplugs. Any water that gets into the ear can be removed by gentle blow-drying.

Patients with evidence of significant immunocompromise or failure to improve in 1 to 2 days should be considered for admission to the hospital to be evaluated for more extensive disease.

Drying the ear after swimming or showering helps prevent otitis externa. Placing drops of acetic acid (vinegar) and rubbing alcohol in the ear two or three times a week during periods of heavy water exposure (summer vacation) helps dry the ear and restore the acidic environment that protects against otitis externa.

Otitis Media (Acute and Chronic)

Accumulation of fluid in the middle ear (medial to the tympanic membrane) is termed otitis media. Fluid collections can be clinically sterile, as in barotrauma-mediated effusions or chronic otitis media with effusion, or can result from infectious causes (acute otitis media [AOM]). Infection-mediated effusions may be serous (usually viral in origin) or suppurative (primary or secondary bacterial infection). The common link between all these processes is eustachian tube dysfunction. The eustachian tube acts as a vent and conduit between the middle ear and posterior pharynx in which air pressure between the middle ear and ambient air is equalized and fluid can drain from the middle ear cavity. After infections (primarily upper respiratory infections [URIs]), edema can cause blockage of the tube. Air is easily absorbed through the middle ear tissues, thereby leading to a relative negative pressure in the middle ear. This negative pressure draws fluid into the enclosed cavity. Native or invasive bacteria can work their way into this enclosed area and proliferate.4,5 Common bacterial pathogens are the same as those frequently found in sinus infections and include Streptococcus pneumoniae, nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Currently, approximately 60% to 70% of S. pneumoniae species are covered by the polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine (Pneumovax).6,7

Otitis media is one of the most common reasons for pediatric physician visits, with estimates that $5 billion is spent as direct or indirect costs annually. A significant proportion of cases are probably misdiagnosed, and guidelines have been issued to ensure proper diagnosis and thus curb wasting of resources.8 “Visualization of the tympanic membrane with identification of a middle ear effusion and inflammatory changes is necessary to establish the diagnosis with certainty.”8 Effusions are signified on physical examination by bulging of the tympanic membrane, bubbles or fluid levels behind the membrane, loss of the light reflex (opacification or cloudiness of the membrane), and (most definitively) loss of tympanic membrane mobility on pneumatic insufflation. Newer modalities, such as acoustic reflectometry and tympanometry, also demonstrate middle ear effusions but are not available in many EDs. Tympanic membrane injection (common in crying children) or the presence of fluid alone is not enough to make the diagnosis of AOM. Accompanying fever, pain, purulent drainage, or other systemic signs point to acute infection.

The role of infectious organisms in chronic otitis media is unclear. It was originally thought to be a noninfectious entity, but studies have shown the presence of bacteria (and bacterial DNA, mRNA, and proteins) in a biofilm model of chronic otitis media.9 Current guidelines offer the option of a trial of antibiotics (typically amoxicillin) or watchful waiting as treatment.8

Treatment

American physicians have historically treated otitis media with antibiotics, whereas European physicians are typically less likely to do so. A 2005 study compared immediate antibiotic treatment with watchful waiting for nonsevere otitis media.10 In the watchful waiting group, 66% of children had complete resolution of symptoms with no antibiotic treatment, no adverse outcomes, cost savings, and similar patient satisfaction.

Treatment options and recommendations by the American Academy of Pediatrics for acute otitis media include the following8:

1. Pain management must be addressed in patients with AOM. Particular attention should be paid to pain management in the first 24 hours of any treatment regimen.

2. Observation without the use of antibacterial agents is an option for the first 2 to 3 days in selected children11 (Table 27.1). The child must be otherwise healthy and in a sound social environment with an adult capable of watching the child closely and returning to the physician if the condition deteriorates.

3. If antimicrobial treatment is chosen, the first-line agent should be amoxicillin, 80 to 90 mg/kg/day. With treatment failures or cases in which broader β-lactamase coverage is desired, amoxicillin, 90 mg/kg, with clavulanate, 6.4 mg/kg, in two divided doses can be used. Penicillin-allergic patients (non–type 1) can be treated with a third-generation cephalosporin (cefdinir, cefpodoxime, cefuroxime, or ceftriaxone). For patients with severe type 1 penicillin allergy, alternative treatments include azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin-sulfisoxazole, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. Treatment is aimed at common pathogens, including S. pneumoniae, nontypeable H. influenzae, and M. catarrhalis. Mycoplasma species can also cause otitis media and are often responsible for blister formation on the tympanic membrane (bullous myringitis). Multiple virus species can cause otitis media and are obviously unaffected by antibiotics.

4. Failure of response in 2 to 3 days should prompt initiation of or a change in antibiotic treatment. If amoxicillin fails, alternatives include amoxicillin-clavulanate, cephalosporin (ceftriaxone), macrolides, and sulfa preparations.

| AGE | CERTAIN DIAGNOSIS OF ACUTE OTITIS MEDIA | UNCERTAIN DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|

| <6 mo | Antibacterial therapy | Antibacterial therapy |

| 6 mo to 2 yr | Antibacterial therapy | Severe illness: antibacterial therapy Nonsevere illness: observation option* |

| ≥2 yr | Severe illness: antibacterial therapy Nonsevere illness: observation option* |

Observation option* |

* Observation: defer antibiotic treatment for 48 to 72 hours.

From Johnson NC, Holger JS. Pediatric acute otitis media: the case for delayed antibiotic treatment. J Emerg Med 2007;32:279-84.

Some authorities have suggested a compromise between meeting patients’ expectations and decreasing the inappropriate overuse of antibiotics.12,13 Patients can be given a “rescue” prescription, which they should have filled only if no improvement occurs in 2 to 3 days.

1. Pneumatic otoscopy should be used to identify the presence of effusion.

2. The history and physical examination (to search for acute signs and symptoms of inflammation or infection) should be used to distinguish this disorder from AOM.

3. Otitis media with effusion should be managed with watchful waiting for 3 months in children who are not at risk for speech, language, or other learning disabilities.

4. Hearing tests (referral to an otolaryngologist) should be performed if the disease lasts longer than 3 months or earlier if any language, learning, or hearing problems are suspected.

5. Antihistamines and decongestants are ineffective and should not be used as treatment; antimicrobial agents and steroids do not have long-term efficacy and should not be used for routine management.

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Otitis Media

Most patients with otitis media can be treated as outpatients.

If antibiotic therapy is chosen, patients should be counseled to take the entire course of antibiotic therapy.

Watchful waiting with a rescue prescription can be chosen for healthy-appearing patients older than 2 years. Parents should be educated about signs of worsening infection, including pain and fever.

Patients should follow up with their primary physicians or return to the emergency department if no improvement occurs in 1 to 3 days.

Patients should be warned of the signs and symptoms of intratemporal and intracranial complications (headache, neck stiffness, vomiting, altered mental status).

Patients should also be apprised of the risks associated with otitis media with effusion and must be sure to follow up with their primary physicians to alleviate the risk for hearing deficits.

Necrotizing (Malignant) Otitis Externa

Necrotizing otitis externa (formerly known as malignant otitis externa) is aggressive extension of infection from the auditory canal to the skull base and other nearby bony structures. This complication occurs nearly exclusively in immunocompromised hosts, with elderly diabetic patients accounting for most of the affected population. It can be the initial complaint in patients with undiagnosed diabetes, and all patients with progressive ear infection need prompt evaluation for diabetes. The emergence of widespread human immunodeficiency virus infection now puts children at risk for a condition that was once almost exclusively an adult disease.14

More than 95% of cases of necrotizing otitis externa are caused by P. aeruginosa, and antibiotic therapy should be aimed at this organism. Since the introduction of semisynthetic penicillins, antipseudomonal cephalosporins, and antipseudomonal fluoroquinolones, mortality from this disorder has decreased from 50% to 10%. Empiric treatment with ciprofloxacin, 400 mg intravenously every 8 hours, is reasonable. Alternative treatments are an antipseudomonal penicillin (e.g., ticarcillin-clavulanate [Timentin], 3.1 g intravenously every 6 hours) and cephalosporins (e.g., ceftazidime, 1 to 2 g every 8 hours). Recently, resistance of P. aeruginosa to ciprofloxacin has been reported to be as high as 33%. Resistance is related to widespread use of quinolones for the treatment of URIs, topical preparations for otitis media and externa, and inadequate treatment courses in patients with malignant otitis externa.15

Ramsay Hunt Syndrome

The combination of ear pain, ipsilateral facial paralysis, and vesicular lesions characterize Ramsay Hunt syndrome, also known as herpes zoster oticus. This reactivation of latent varicella-zoster infection in the geniculate ganglion with spread to the eighth cranial nerve (and frequently cranial nerves V, IX, and X) results in both auditory and vestibular dysfunction.16

Treatment is aimed at shortening the duration of the outbreak and controlling symptoms. Acyclovir and steroids are often used, but no clear prospective studies have been undertaken. In light of the known safety and effectiveness of anti–varicella-zoster or anti–herpes simplex drugs, acyclovir (800 mg five times per day) or famciclovir (500 mg three times per day) should be strongly considered, along with added prednisone.17 Aggressive analgesia is frequently needed for pain control. Vestibular symptoms can be treated with meclizine or diphenhydramine. Cranial nerve VII palsies can occur and lead to an inability to close the eye, which can cause drying and abrasions. Use of a moisturizer or lubricant ophthalmic ointment (Lacri-Lube) or other measures to moisten and protect the eye are often needed.

Foreign Body

Methods of foreign body removal are as follows:

• Irrigation: An intravenous catheter without a needle (18 to 20 gauge) can be used with a 10- to 20-mL syringe. Irrigating the superior portion of the canal seems to provide the best results. The force generated is well below that needed to perforate a normal tympanic membrane. Materials that swell when wet (vegetables, cellulose, wood) should not be removed by this method because of the risk for further swelling.

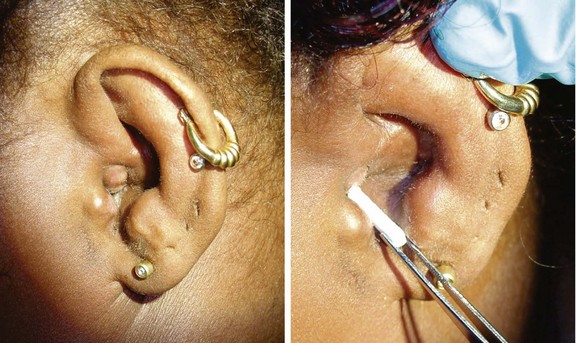

• Forceps: Small forceps (alligator forceps) can be used to grasp objects. Use of an ENT scope and speculum greatly facilitates the process (Fig. 27.3).

• Cyanoacrylate: A small amount of cyanoacrylate (e.g., Super Glue) can be applied to the blunt end of a cotton-tipped applicator and held against the impacted object for about 60 seconds to glue the foreign body to the applicator and allow gentle removal of it. This method should not be attempted in a moving, uncooperative patient.

• Right-angle probe: A small probe can sometimes be worked behind the object and used to pull it forward. This works best for loose or pliable objects.

• Suction: A flanged end of thin plastic tubing (or a premade suction device) can sometimes be used to grasp smooth, regularly shaped objects (beads) or pieces of insects for removal.

Cerumen, or earwax, is a naturally occurring substance that cleans, protects, and lubricates the external auditory canal. Excessive accumulation of cerumen is one of the most common reasons that patients seek medical care for ear-related reasons. When associated with symptoms, it is recommended that clinicians use ceruminolytic agents (triethanolamine, docusate sodium, saline), irrigation, or manual removal to treat a patient with impacted cerumen.18

Sudden Hearing Loss

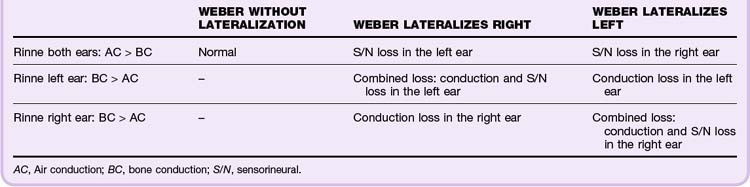

Tuning fork tests provide the best clues to distinguish between conductive and sensorineural hearing loss. The key component of the test is to compare how well the ear hears conduction through bone versus conduction through air. A 512-Hz fork should be used. The Weber test compares the two ears with each other (Fig. 27.4). A vibrating fork is placed midline on the top of the head or between the front top teeth (some patients find this intolerable). The patient is asked which ear hears the vibrations better. Because outside sounds (from air conduction) suppress the perception of vibratory conduction, an ear with a conductive hearing defect will “hear” the fork vibrating through bone “louder” than the other ear will. So if the fork is heard louder in one ear, either that ear has a conductive deficit or the other ear has a neural deficit (Table 27.2).

The Rinne test evaluates each ear independently (see Fig. 27.4). Normally, air conduction is more sensitive than bone conduction, and one should be able to hear a vibrating fork longer through the air than through bone. The handle of a vibrating fork is placed on the mastoid process of the side being evaluated. The vibrating end is then held near the ear canal. Normally functioning ears hear the air conduction louder and longer than the bone conduction. Perception of sound better through bone conduction indicates a conductive deficit. Lack of hearing either bone or air conduction points to sensorineural hearing loss (see Table 27.2).

Treatment

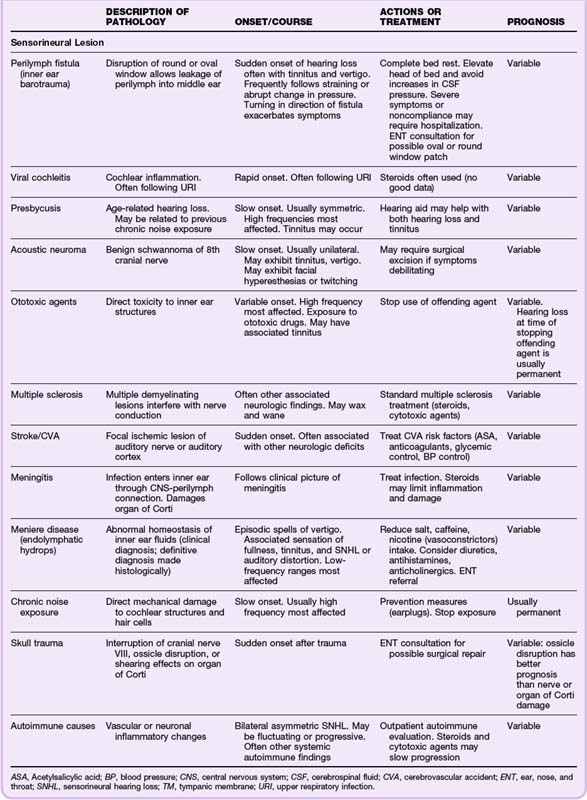

Treatment options for hearing loss are limited in the ED environment and are governed by the physical findings (Table 27.3).

Fluid collections in the middle ear dampen the vibrations of the ossicles and decrease the transmission of sound waves, thereby resulting in a relative conductive hearing deficit. Acute middle ear fluid collections may respond to decongestants alone. If evidence of infection (otitis media) is present, antibiotics may be added to the treatment regimen. Solid masses may be seen behind the tympanic membrane but are not usually treatable in the ED. All patients with chronic fluid collections and masses require referral to an otolaryngologist because studies have indicated a connection between increased duration of middle ear disease and extent of sensorineural hearing loss.19,20

Sensorineural hearing loss may stem from several causes, but there are few emergency treatment options. The patient can be counseled about the variable recovery rate, and some prognosis may be given on the basis of the suspected cause of the lesion. Viral causes and inflammatory or autoimmune causes may respond to steroid treatment started in the first few days. Steroids have been regarded as standard therapy for sensorineural hearing loss suspected to be of viral etiology, although no controlled trials have shown significant benefit.21,22 Steroids should be prescribed with caution, and care must be taken to rule out infections, which may worsen with steroid treatment. Steroids should be given only if prompt follow-up is ensured. Antiviral agents (acyclovir, famciclovir, valacyclovir) are also commonly prescribed because of the possible role of herpes simplex virus type 1 as an etiologic agent in sensorineural hearing loss. No clear evidence has, however, shown a better outcome with steroids plus antiviral agents than with steroids alone.23–25

1 Ho T, Vrabec J. Otomycosis: clinical features and treatment implications. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:787–791.

2 Rosenfeld RM, Brown L, Cannon CR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:S4–23.

3 Van Balen FA, Smith WM, Zuithoff NP, et al. Clinical efficacy of three common treatments in acute otitis externa in primary care: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2003;327:1201–1205.

4 Rovers MM, Schilder AG, Zielhuis GA, et al. Otitis media. Lancet. 2004;363:465–473.

5 Daly KA, Giebink GS. Clinical epidemiology of otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:S31–S36.

6 Klein JO. Microbiology. Bluestone CD, Klein JO. Otitis media in infants and children, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2001.

7 Hausdorff WP, Yothers G, Dagan R, et al. Multinational study of pneumococcal serotypes causing acute otitis media in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:1008–1016.

8 American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Management of Acute Otitis Media. Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1451–1465.

9 Ehrlich GD, Veeh R, Wang X, et al. Mucosal biofilm formation on middle-ear mucosa in the chinchilla model of otitis media. JAMA. 2002;287:1710–1715.

10 McCormick DP, Chonmaitree T, Pittman C, et al. Nonsevere acute otitis media: a clinical trial comparing outcomes of watchful waiting versus immediate antibiotic treatment. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1455–1465.

11 Johnson NC, Holger JS. Pediatric acute otitis media: the case for delayed antibiotic treatment. J Emerg Med. 2007;32:279–284.

12 Cates C. An evidence based approach to reducing antibiotic use in children with acute otitis media: controlled before and after study. BMJ. 1999;318:715–716.

13 Siegel RM, Kiely M, Bien JP, et al. Treatment of otitis media with observation and a safety-net antibiotic prescription. Pediatrics. 2003;112:527–531.

14 Rubin Grandis J, Branstetter BF, 4th., Yu VL. The changing face of malignant (necrotizing) external otitis: clinical, radiological and anatomic correlations. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:34–39.

15 Carfrae M, Kesser B. Malignant otitis externa. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008;41:537–549.

16 Sweeney CJ, Gilden DH. Ramsay Hunt syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:149–154.

17 Murakami S, Hato N, Horiuchi J, et al. Treatment of Ramsay Hunt syndrome with acyclovir-prednisone: significance of early diagnosis and treatment. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:353–357.

18 Roland PS, Smith TL, Schwartz SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines: cerumen impaction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139(3 Suppl 2):S1–21.

19 Mehta RP, Rosowski JJ, Voss SE, et al. Determinants of hearing loss in perforations of the tympanic membrane. Otol Neurotol. 2006;27:136–143.

20 Radaelli de Zinis LO, Campovecchi C, Parrinello G, et al. Predisposing factors for inner ear hearing loss associated with chronic otitis media. Int J Audiol. 2005;44:593–598.

21 Wei BP, Mubiru S, O’Leary S. Steroids for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2006. CD003998

22 Slattery WH, Fisher LM, Iqbal Z, et al. Oral steroid regimens for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132:5–10.

23 Stokroos RJ, Albers FW, Tenvergert EM. Antiviral treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a prospective randomized double-blind clinical trial. Acta Otolaryngol. 1998;118:488–495.

24 Uri N, Doweck I, Cohen-Kerem R, et al. Acyclovir in the treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128:544–549.

25 Tucci DL, Farmer JC, Jr., Kitch RD, et al. Treatment of sudden sensorineural hearing loss with systemic steroids and valacyclovir. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:301–308.