40 Dystonia

Primary Dystonia

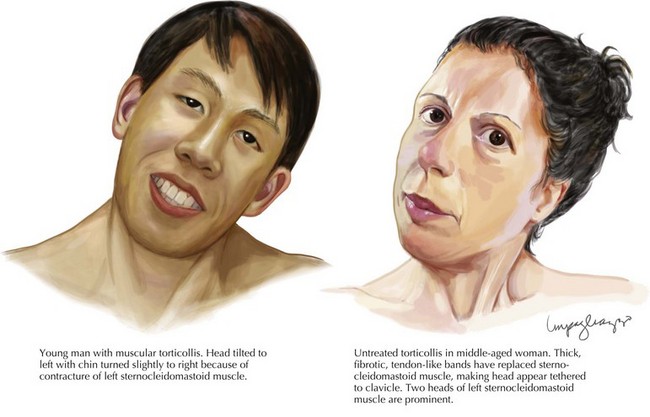

Primary dystonias are characterized by pure dystonia (with the exception that tremor can be present) and they may be sporadic or familial. Most primary dystonias are sporadic with onset in adulthood and a focal or segmental presentation. The most common focal dystonia presenting to movement disorders clinics is cervical dystonia (Fig. 40-1). After cervical dystonia, the most common focal dystonias are blepharospasm, spasmodic dysphonia, oromandibular dystonia, and hand dystonia.

A minority of primary dystonias have an identified genetic etiology (Box 40-1). Perhaps the best studied of the primary dystonias is DYT1 dystonia, or Oppenheim’s dystonia, a generalized torsion dystonia that usually begins in childhood affecting the limbs first. DYT1 dystonia is caused by a deletion in the DYT1 gene, which encodes for the torsin A protein. The disease is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion and has 30–40% penetrance. Phenotype can vary widely within an affected family. The DYT1 mutation is estimated to account for 90% of limb-onset dystonia cases in the Ashkenazi Jewish population and 50–70% of cases in the non-Jewish population. A number of other primary dystonias (DYT6, DYT7 and DYT13) have had their genetic loci mapped (Table 40-1).

Secondary Dystonia

A number of heredodegenerative disorders may present with dystonia. Autosomal dominant disorders (Huntington disease, spinocerebellar ataxia type 3, neuroferritonopathy), autosomal recessive disorders (Wilson disease, pantothenate-kinase associated degeneration), X-linked recessive disorders (DYT3 or Lubag), and mitochondrial disorders (Leigh disease) have been described and are listed in Box 40-2.

Fahn S, Bressman SB, Marsden CD. Classification of dystonia. Adv Neurol. 1998;78:1-10.

Fahn S, Jankovic J. Principles and practice of movement disorders. Churchill and Livingstone. 2007.

Tarsy D, Simon DK. Dystonia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:818-829.

Vidailhet M, Vercueil L, Houeto JL, et al. Bilateral deep-brain stimulation of the globus pallidus in primary generalized dystonia. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:459-467.

Vidailhet M, Vercueil L, Houeto JL, et al. Bilateral, pallidal, deep-brain stimulation in primary generalised dystonia: a prospective 3 year follow-up study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:223-229.